Aguascalientes | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Ciudad de Aguascalientes City of Aguascalientes | |

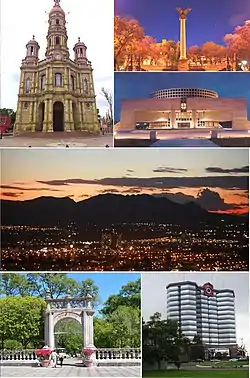

Clockwise from top: San Antonio de Padua Church, La Exedra (main square), Aguascalientes Opera House, Cerro del Muerto, Plaza Bosques Tower and the San Marcos Park. | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Spanish: Ciudad de la gente buena (City of the good people) | |

| Motto(s): Latin: Virtus in Aquis, Fidelitas in Pectoribus (Virtue in the Water, Fidelity in the Heart) | |

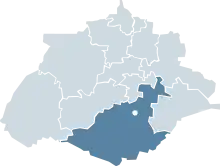

Location of Aguascalientes within the state | |

Location of the state of Aguascalientes | |

| Coordinates: 21°52′33.6″N 102°17′45.6″W / 21.876000°N 102.296000°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| State | Aguascalientes |

| Municipality | Aguascalientes |

| Founded | October 22, 1575 |

| Founded as | Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de las Aguas Calientes |

| Founded by | Juan de Montoro Rodríguez Jerónimo de Orozco |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Leonardo Montañez Castro |

| Area | |

| • City | 385 km2 (149 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,888 m (6,194 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 1,425,607 |

| • Density | 3,700/km2 (9,600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,225,432 |

| Demonyms | hidrocálido, aguascalentense |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Postal code | 20000-20999 |

| Area code | 449 |

| Federal Routes | |

| Website | http://www.ags.gob.mx |

Aguascalientes (Spanish pronunciation: [ˌaɣwaskaˈljentes] ⓘ) is the capital of the Mexican state of the same name and its most populous city, as well as the head of the Aguascalientes Municipality; with a population of 934,424 inhabitants in 2012 and 1,225,432 in the metro area.[1] The metropolitan area also includes the municipalities of Jesús María and San Francisco de los Romo. It is located in North-Central Mexico, which roughly corresponds to the Bajío region (Lowlands) within the central Mexican plateau. The city stands on a valley of steppe climate at 1880 meters above sea level, at 21°51′N 102°18′W / 21.850°N 102.300°W.

Originally the territory of the nomadic Chichimeca peoples, the city was founded on October 22, 1575, by Spanish families relocating from Lagos de Moreno under the name of Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de las Aguas Calientes (Village of Our Lady of the Assumption of the Hot Waters), in reference to the chosen patron saint and the many thermal springs found close to the village, which still remain to this day. It would serve as an outpost in the Silver Route, while politically, it was part of the kingdom of Nueva Galicia.[2] In 1835, President Antonio López de Santa Anna made Aguascalientes the capital of a new territory in retaliation to the state of Zacatecas, eventually becoming capital of a new state in 1857.[3] During the Porfiriato era, Aguascalientes was chosen to host the main workshops of the Mexican Central Railway company; bringing an industrial and cultural explosion. The city hosted the Revolutionary Convention of 1914, an important meeting of war generals during the Mexican Revolution.

Formed on a tradition of farming, mining and railroad and textile industry; contemporary Aguascalientes has attracted foreign investment of automobile and electronics companies due to its peaceful business climate, strategic location and existing infrastructure.[4][5] The city is home to two Nissan automobile manufacturing plants[6][7] and a shared facility by Nissan and Mercedes,[8] which has given the city a significant Japanese immigrant community.[9][10] Other companies with operations in the city include Jatco, Coca-Cola, Flextronics, Texas Instruments, Donaldson and Calsonic Kansei. The city of Aguascalientes is also known for the San Marcos Fair, the largest fair celebrated in Mexico and one of the largest in North America.

History

The city of Aguascalientes was founded on October 22, 1575, by Juan de Montoro, his family and accompanying families. The village was originally conceived as a minor garrison and rest stop between the cities of Zacatecas and Lagos de Moreno, with the end goal of protecting silver in its route to Mexico City from the Chichimeca.[11] Although the founders did not envision it becoming a major city, it would eventually become the capital of a newly formed state when the territory separated from the adjacent state of Zacatecas in 1835.

The historical center of Aguascalientes was born out of four distinct neighborhoods. The oldest of these is the Barrio del Encino, which is technically older than Aguascalientes proper. Founded in 1565 by the Andalusian Hernán González Berrocal, the neighborhood was originally named Triana after the neighborhood in Seville, Spain. The Barrio del Encino is home to the Baroque-style Templo del Señor del Encino, a Catholic church built between 1773 and 1796.[12] The Cristo Negro del Encino ('Black Christ of the live oak'), is a widely venerated religious icon symbolic of this neighborhood. The colonial square and the José Guadalupe Posada Museum, adjacent to the church, are one of the main attractions in the city.

The second neighborhood is the Barrio de San Marcos, which has its roots in the early 17th century as an indigenous settlement on the outskirts of the then-village of Aguascalientes. Between 1628 and 1688, some communal land was allocated to the community, but the indigenous people still worked on Spanish-owned farms and produced goods to sell in Aguascalientes. Meanwhile, they organized the construction of a simple hospital and a chapel. This original chapel was replaced by the current Templo de San Marcos completed on December 15, 1763; this church is the spiritual headquarters of the Feria Nacional de San Marcos.

The third neighborhood is the Barrio de Guadalupe, which began its development as a string of shops and trading posts alongside the road leading from Aguascalientes to Jalpa and Zacatecas during the latter half of the 18th century. The neighborhood's iconic Templo de Guadalupe was built between 1767 and 1789; it is recognized for its Spanish Baroque façade and its dome lined with Talavera tiles. Especially after the founding of the Fundición Central Mexicana ('Mexican Central Foundry'), the neighborhood developed quickly; by the early 20th century its roadside inns had mostly been converted into homes and its boundaries had blurred with those of the Barrio de San Marcos.

The final neighborhood is the Barrio de la Salud, which has its roots in a small chapel and a cemetery developed towards the end of the 18th century to deal with a number of disease epidemics that had struck the area. Gravediggers established homes near the cemetery, and others took advantage of the open land to establish orchards. Though the orchards began to disappear during the early 20th century, clues as to the neighborhood's roots still remain. First of all, the fact that property lines generally followed irrigation ditches can still be seen in the neighborhood's haphazard street grids today. Second, the neighborhood's working-class character is visible in its primarily single-story homes featuring simple façades.[13]

A fifth neighborhood, the Barrio de la Estación, named after the town's central train station, is often grouped in with the city's original neighborhoods.[14] However, this neighborhood is considerably more modern, with much of its development dating from the final decades of the 19th century or later.[15] Therefore, despite its important role in the history of Aguascalientes, it is not strictly accurate to consider the Barrio de la Estación one of the city's original historical neighborhoods.

Geography

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Aguascalientes has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh). Most of the precipitation is concentrated from June to September.

| Climate data for Aguascalientes (1951–2010, extremes 1947–2018) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.5 (85.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.0 (104.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

39.5 (103.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.0 (21.2) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14.1 (0.56) |

9.5 (0.37) |

4.3 (0.17) |

8.8 (0.35) |

17.9 (0.70) |

88.1 (3.47) |

119.9 (4.72) |

120.4 (4.74) |

90.1 (3.55) |

35.4 (1.39) |

10.2 (0.40) |

11.8 (0.46) |

530.5 (20.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 9.7 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 64.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50.7 | 46.7 | 39.1 | 39.4 | 42.4 | 53.1 | 60.1 | 59.2 | 60.6 | 58.4 | 53.2 | 52.8 | 51.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 231.7 | 243.3 | 273.1 | 267.6 | 267.3 | 218.3 | 203.7 | 229.7 | 202.9 | 230.4 | 247.1 | 223.6 | 2,838.7 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional,[16][17] World Meteorological Organization (relative humidity and sun 1981–2010)[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Colegio de Postgraduados[19] | |||||||||||||

Etymology

The name originates from the Spanish words aguas calientes, meaning 'hot waters', although a more accurate translation is 'hot springs', part of the original name of Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de las Aguas Calientes (Village of our Lady of Assumption of the Hot Springs). When the city was first settled by Juan de Montoro and twelve families, it was given this name for its abundance of hot springs. These thermal features are still in demand in the city's numerous spas and even exploited for domestic use. People from Aguascalientes (both the city and the state) are known by the whimsical demonym hidrocálidos or "hydrothermal" people.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 797,010 | — |

| 2015 | 877,190 | +10.1% |

| 2020 | 948,990 | +8.2% |

| [20][21][22][23] | ||

As of 2010, the city of Aguascalientes proper had a population of 797,010. The two other municipalities considered parts of the Aguascalientes metropolitan area are Jesús María and San Francisco de los Romo; they had populations of 99,590 and 35,769, respectively. As such, the Aguascalientes metropolitan area had a total population of 932,369.[24]

According to the latest census by the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Data Processing (INEGI), Aguascalientes City was the 13th largest metropolitan area by population in the country. It is one of the fastest-growing cities in Mexico.

Economy

Aguascalientes is home to two large Nissan manufacturing plants, including the most important outside of Japan. Among other models of cars, they manufacture the Sentra and the Versa. The Aguascalientes plants are responsible for the majority of Mexico's overall annual production of 850,000 Nissan automobiles.[25] Due to their presence, the city has a significant Japanese population.

Texas Instruments has one plant in Aguascalientes, which is dedicated to integrated circuitry (IC) manufacturing. Sensata Technologies has one plant in the city, making sensors and controls for automotive, HVAC and industrial use. Flextronics is another electronics manufacturer that has a plant located in Aguascalientes City. There are also several companies that work in the robotics industry, the most notable being FANUC Robotics.

Transport

%252C_Aguascalientes%252C_Ags._16.JPG.webp)

Cycling

The municipality is developing a system of interconnected green bicycle routes, greenways, the aim being to facilitate fast, safe, and pleasant bicycle transport from one end of the city to the other.[26]

Roads

Aguascalientes has a large network of roads connecting different municipalities of the city together and to other cities. Most of the city grew as a planned city, having been pioneers in urban development regulation since 1936. The city is planned around three concentric highway loops. The third beltway loop is expected to be fully operational in 2022. The first and second loop have overpasses and underpasses at major intersections to avoid traffic from stopping.

Airport

Lic. Jesús Terán Peredo International Airport serves the city, with four daily non-stop international flights from/to Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston and Chicago; as well as domestic flights.

Culture and recreation

Aguascalientes houses the largest festival held in Mexico, the San Marcos Fair, which takes place from the middle of April to the beginning of May. The celebration was held originally in the San Marcos church, neighborhood, and its magnificent neoclassical garden; since then, it has greatly expanded to cover a huge area of exposition spaces, bullrings, nightclubs, theaters, performance stages, theme parks, hotels, convention centers, and other attractions. It attracts almost 7 million visitors to Aguascalientes every year.

The old part of the city revolves around downtown and the four original neighborhoods from which the city expanded. The most notable building here is the Baroque Government Palace, dating from 1664 and constructed out of red volcanic stone; it is known for its one hundred arches. The prominent Baroque Cathedral, begun in 1575, is the oldest building in the city. The tall column in the center of the main square dates from colonial times; it held a statue of a Spain's viceroy, which was toppled when the country gained independence; the current sculpture on its summit commemorates Mexican independence.

Neighborhoods and tradition

The city of Aguascalientes is made up of four traditional neighborhoods, all of which grew up around the central Plaza de la Patria; Guadalupe, San Marcos, El Encino and La Estación.

Guadalupe neighborhood, a traditional producer of pottery, centers around its local church. Located in the heart of Guadalupe, this religious sanctuary, the second most important in the city and dating back to the late 18th century, has a Baroque façade and a large dome covered in traditional talavera tiles. Inside it has many flower and angel motifs.

The next is San Marcos, founded in 1604 and once home to natives of Tlaxcala state who fled persecution. Today, the area hosts the traditional San Marcos Fair in springtime. There is San Marcos Gardens, a green spot where paths and trees are abundant. The gardens are traditionally frequented by poets, artists and lovers. Directly in front of the gardens is the Baroque San Marcos Temple, its tiled dome glinting in the sun.

Last but not least, the neighborhood of La Estación takes its name from the old railway station, inaugurated in 1911 and one of Aguascalientes' architectural and historical treasures.

Aguascalientes historic downtown is home to several museums including the Aguascalientes Museum (Museo de Aguascalientes), the city's art museum, housed in a Classical-style building designed by the self-trained architect Refugio Reyes; the Guadalupe Posada Museum (Museo Guadalupe Posada), located in the historic nationhood of Triana, exhibits the life and work of José Guadalupe Posada; and the State History Museum, which is housed in an elegant Art Nouveau mansion typical of the Porfirian period with and ornate patio and dining room with vegetable motifs in a Mediterranean style, with a French Academism façade, and interior columns and an arcade of pink stone characteristic of Porfirian Eclecticism.

Other designs by Refugio Reyes include the Paris Hotel, the Francia Hotel, and his masterpiece, the Church of San Antonio. The Church of our Lady of Guadalupe possesses an extraordinarily exuberant Baroque facade designed by José de Alcíbar, a renowned architect of the period considered to be one of the most famous artists in Mexico in the 1770s. The Camarin of the Immaculate in the church of San Diego is considered by historians to be the last Baroque building in the world; it links the Baroque and Neoclassical styles; it is the largest of the fewer than ten of these type of structures built in the whole continent.

Aguascalientes is also home to some of the country's leading provincial theaters. Examples are the Morelos Theater, historically important for its role during the Mexican Revolution as a convention site; architecturally, the building is notable for its facade and interior, which houses a small museum. The Teatro Aguascalientes is the city's premier theatre and opera house.

In addition, in the modern section of the city, the Museo Descubre astonishes as an interactive museum of science and technology. It also features an IMAX screen. The Museum of Contemporary Art is the city's art museum.

The gothic structure of the Los Arquitos cultural center used to be one of the first bathhouses in the city, declared a historic monument in 1990. The Ojocaliente is also an original bathhouse still in use today, and fed with thermal springs. La Estacion Historic Area (The Old Train Station Complex) contains the Old Train Station and Railway Museum historic complex, which at some point in 1884 formed the largest rail hub and warehouses in all Latin America. The complex is adorned with dancing fountains, a railway plaza and original locomotives and monuments. It was in this complex that the first locomotive completely manufactured in Mexico was made. It symbolizes the progress of the city and its transformation from the rural to an emergent industrial economy. The rail factories supplied with railways and locomotives to whole of Mexico and Central America. The Train Station is also historic due to its unusual (for Mexico) English architectural style. The Alameda avenue, the railway hangars, the factory complexes, and its surrounding housing have been proposed to be placed in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Media

Metroaguascalientes was one of the radio stations for the city of Aguascalientes.[27]

State-owned Radio y Televisión de Aguascalientes (RyTA) offers local programming as well as news shows.

Sports

Football

Club de Fútbol Gallos Hidrocálidos de Aguascalientes was a football club from Aguascalientes, Mexico.

The club was founded in 1994, when Salvador López Monroy, a restaurant business owner from Los Angeles,[28] bought a second division franchise which he relocated to Aguascalientes where there was no professional football club.[29]

The club played its last tournament in 2000–2001 when the Governor of Aguascalientes bought first division club Necaxa, with its national following, and relocated it from Mexico City. Gallos de Aguascalientes was then sold to Chivas, which changed its name to F.C. Tapatio de Guadalajara, affiliated to Chivas.[29]

The city is home to the soccer team Club Necaxa, which plays in Mexican first division. The club left Mexico City and relocated to Aguascalientes following the 2003 opening of Estadio Victoria, which is now the club's home venue and one of the best stadiums in the country.

Basketball

Panteras de Aguascalientes its part of the Mexican basketball league National Professional Basketball League (LNBP). In 2003, the Panteras won the championship of the LNBP. The Panteras play their home games at the Gimnasio Hermanos Carreón.

Baseball

The baseball team Rieleros de Aguascalientes, returned to the Mexican League in 2012. The team previously won the championship in 1978.

Cycling

The Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, designed by Peter Junek, hosted the 2010 Pan American Track Championships. At an elevation of 1887m, the Velodrome is a frequent location for attempts at breaking the Cycling Hour Record.

Notable people

- José María Bocanegra, lawyer, interim President of Mexico in December 1829, minister in the national government 1833–44

- Manuel M. Ponce, musician

- José Guadalupe Posada, illustrator

- Saturnino Herrán, painter

- Yadhira Carrillo, telenovela actress and beauty pageant

- Ernesto Alonso, telenovela director/actor

- Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, film director

- José María Napoleón, singer/composer

- Luis Gerardo Méndez, actor and producer

- Violeta Retamoza, golfer

- Gabriela Palacio, beauty pageant titleholder

- Karina González, beauty pageant titleholder

- William Yarbrough, Mexican-born American soccer player who played for Liga MX club León and the United States national team

- Wendolly Esparza, American-born Mexican television personality best known for winning Miss Mexico 2014 and placing top 15 in Miss Universe 2015.

In popular culture

- Aguascalientes was the hometown of Esperanza Ortega in the book Esperanza Rising.

- The Festival de Calaveras, is a tribute made to the La Catrina created by José Guadalupe Posada, this colorful festival arises with the aim of rescuing and preserving the traditions of the Día de Muertos

- Mexican engraver, illustrator and caricaturist José Guadalupe Posada was born in the city of Aguascalientes

- Mexican painter Saturnino Herrán was born in the city of Aguascalientes

- In 2016, American comedian, actress, television host, and producer Chelsea Handler visited Aguascalientes with a piñata effigy of Donald Trump for her Netflix Original talk show

References

- ↑ Javier Rodríguez Lozano. "En estos días Aguascalientes llegará al millón de habitantes – La Jornada Aguascalientes (LJA.mx)". La Jornada Aguascalientes (LJA.mx). Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Aguascalientes, traditional city in Mexico". Visitmexico.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Historia de la Ciudad de Aguascalientes". Ags.itesm.mx. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ Davies, Peter (December 22, 2017). "Aguascalientes leads in economic growth, Querétaro second". Mexico News Daily. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Of cars and carts". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Nissan Mexicana Opens Third Plant, Boosts Production for Sentra". myAutoWorld.com. November 13, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ↑ Newsroom, M. D. P. (December 15, 2022). "Nissan's A1 plant in Aguascalientes is the fastest-growing in the world - Aguascalientes Daily Post". Mexico Daily Post. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Mercedes And Infiniti To Build Vehicles At New Factory In Mexico".

- ↑ "COMPAS, the complex manufacturing of strategic cooperation between Daimler and Renault-Nissan Alliance intensifies recruiting the best talent for the production of premium vehicles in Aguascalientes". Automotive World. May 11, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Newsroom, M. D. P. (October 5, 2021). "Foreigners in Aguascalientes... How many are they? -". Mexico Daily Post. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ↑ Díaz Márquez, Ilse. "Fundación de Aguascalientes". Gobierno del Estado de Aguascalientes. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Barrio del Encino (Barrio de Triana)". Gobierno del Estado de Aguascalientes. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ Dobrowolski, Jim (February 2, 2017). "The Four Historical Neighborhoods of Aguascalientes". Spanish Learner Central. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Barrios de Aguascalientes, México | VisitMexico". www.visitmexico.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Barrio de la Estación". Gobierno del Estado de Aguascalientes. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Estado de Aguasalientes-Estacion: Aguascalientes". Normales Climatologicas 1951–2010 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Extreme Temperatures and Precipitation for Aguascalientes (DGE)" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ↑ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Normales climatológicas para Aguascalientes, AGS" (in Spanish). Colegio de Postgraduados. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Localidades y su población por municipio según tamaño de localidad" (PDF) (in Spanish). INEGI. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Número de habitantes". INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography). Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Tabulados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015" (xls) (in Spanish). INEGI. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Tabulados del Cuestionario Básico – Aguascalientes" [INEGI. 2020 Population and Housing Census. Basic Questionnaire Tabulations – Aguascalientes] (Excel) (in Spanish). INEGI. 2020. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Número de habitantes. Aguascalientes". cuentame.inegi.org.mx. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ Ltd., NISSAN MOTOR Co. "NISSAN | NISSAN INAUGURATES ALL-NEW AGUASCALIENTES, MEXICO PLANT, BUILDING ON A REPUTATION FOR QUALITY AND EFFICIENCY". www.nissan-global.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Se implementará en Aguascalientes el proyecto de Movilidad en Bicicleta del DF". La Jornada Aguascalientes (LJA.mx). Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ Zapato Cabral, Jose Antonio (February 9, 2007). "Noticias_locales_del_09_de_febrero_de_2007". noticiero (in Spanish). METROAguascalientes. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ↑ "Desfalco a los Gallos" [Embezzlement in the Roosters] (in Spanish). Imagen. June 19, 1999. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013.

- 1 2 García Esparza, Karla Lizbeth (July 31, 2012). "Desmienten Regreso de los Gallos de Aguascalientes al Futbol Profesional" [Roosters of Aguascalientes denied a return to professional football] (in Spanish). Pagina 24. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013.

Bibliography

External links

- Municipal website

- Fotos, Mensajes, y Mas de Aguascalientes

- Link to tables of population data from Census of 2005 INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática