| Aigialosuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

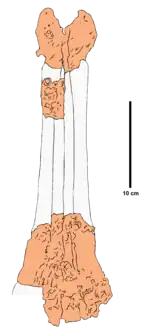

| Teeth attributed to Aigialosuchus sp. found in the Kristianstad Basin | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Clade: | Crocodylomorpha |

| Family: | †Dyrosauridae |

| Genus: | †Aigialosuchus Persson, 1959 |

| Species: | †A. villandensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Aigialosuchus villandensis Persson, 1959 | |

Aigialosuchus is an extinct genus of long-snouted crocodylomorph that lived in what is now Sweden during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period. The name Aigialosuchus comes from the Greek αἰγιαλός (aigialos), meaning "seashore", and σοῦχος (souchus), meaning "crocodile". The genus contains a single species, A. villandensis, described in 1959 by Per Ove Persson based on material recovered from the Kristianstad Basin in southern Sweden.

The known fossil material of Aigialosuchus consists of a partial skull and isolated teeth from southern Sweden, with possible additional teeth found on Zealand in Denmark. The fragmentary nature of these remains means that the precise classification of the genus remains uncertain. Though typically classified as an eusuchian, since 2016 it has been repeatedly placed within the more basal family Dyrosauridae.

In the Cretaceous, southern Scandinavia was covered by shallow sea and the Ivö Klack site within the Kristianstad Basin, where most of the fossils referred to Aigialosuchus have been found, was a small and rocky island. Many other dyrosaurids were marine, a lifestyle possibly shared by Aigialosuchus since its fossils have been discovered in marine deposits. Its teeth were short and stout, possibly an adaptation towards feeding on large fish and invertebrates.

History of research

Aigialosuchus was described by Swedish paleontologist Per-Ove Persson in 1959 based on fossil material recovered at the Ivö Klack locality in the Kristianstad Basin. The generic name derives from the Greek αἰγιαλός (aigialos), meaning "seashore", and σοῦχος (souchus), meaning "crocodile".[1] The species name of the only species referred to the genus, A. villandensis, derives from the Villand district of Skåne, where the fossils were found. The material Persson based Aigialosuchus on were the remains of the anterior part of the skull and of the mandibles, including some detached teeth, belonging to a single individual. Persson considered this material to be enough to clearly differentiate the fossil animal from all other known long-snouted crocodylomorphs, noting that the main distinguishing feature was the nasal bone of Aigialosuchus extending to the fenestra exonarina communis (a fusion of the fenestrae exonarinae, or bony nostrils, of both sides of the skull).[2]

In 2017, Greenlandic paleontologist Jan S. Adolfssen, Danish paleontologist Jesper Milàn and American paleontologist Matt Friedman noted that a single, rather blunt and wide crocodylomorph tooth from the Faxe quarry in the Middle Danian-aged Faxe Formation at Faxe, Denmark, might be referrable to either Aigialosuchus or to some genus within the Alligatoroidea.[3] A similar tooth also discovered in Early to Middle Paleocene deposits, this time at Gemmas Allé in Copenhagen, in 2014, also accorded well with Persson's description of Aigialosuchus teeth, though it was not referred to the genus due to the lack of a formal comparison to the type material.[4]

Description

Aigialosaurus was a long- and narrow-snouted crocodylomorph.[1][5][6] The bony nostrils on both sides of the head were fused to form a single larger fenestra (skull opening), dubbed by Persson as a fenestra exonarina communis. The nasal bones on both sides of the skull extended forwards until reaching the margin of this skull opening, this being the main diagnostic feature of the genus.[7] Another diagnostic feature is the mandibular symphysis (the connection between the left and right mandible) of Aigialosuchus being unusually long,[1] 13.8 centimetres (5.4 inches),[8] and being reached by the splenial bone.[1]

The foremost part of the skull of Aigialosuchus was broadened considerably and separated from the rest of the skull by paired notches on both sides, at the level of the fourth mandibular teeth, similar to the condition in many other crocodylomorphs. The widest portion of the broadened part is 7.1 centimetres (2.8 inches) wide and the width at the point of the notches is just 4.7 centimetres (1.85 inches).[2] The foremost part of the lower jaw, which is generally narrow similar to the upper jaw, was broadened as well, though not to the same extent as the snout.[8]

In contrast to modern crocodylians, which typically have long and slender teeth, the teeth of Aigialosuchus were stout and short.[5][8] The teeth were also somewhat recurved and had cylindrical roots. The surface of the teeth was striated (covered in ridges) densely from the base to the tip.[8]

Classification

Persson classified Aigialosuchus as a true crocodile, placing it within the subfamily Crocodylinae.[1] He based this on the distinct notch in the upper jaw. Persson also noted that since Aigialosuchus is quite poorly known, detailed comparisons with other crocodylines were impossible.[2]

Persson's classification of Aigialosuchus as a crocodyline is no longer considered likely. In 2001, American paleontologist Christopher Brochu noted that Aigialosuchus was an enigmatic crocodyliform, but probably a eusuchian (the group that contains all living crocodilians).[9] Because of the fragmentary material, Aigialosuchus was considered a problematic taxon by French paleontologist Jeremy E. Martin and Italian paleontologist Massimo Delfino in 2010, though they noted, like Brochu, that it was likely to have been a eusuchian. Although the narrow snout of Aigialosuchus is similar to the narrow snouts within the genera in the Gavialoidea (today containing only the gharial), they considered it to be unlikely that Aigialosuchus is part of that superfamily on account of the nasal of Aigialosuchus contributing to the posterior margin of the bony nostrils.[4]

In 2014, German paleontologist Daniela Schwarz-Wings and Danish paleontologists Jesper Milàn and Palle Gravesen considered the features of Aigialosuchus to accord better with the Crocodyloidea than with the Gavialoidea, but noted that Aigialosuchus significantly predated the earliest similar crocodyloid genera. Schwarz-Wings, Milàn and Gravesen noted that until a taxonomic revision of the Aigialosuchus material is carried out, its precise systematic position within the entire Crocodylomorpha will remain unclear.[4]

In 2014, French paleontologists Jeremy E. Martin, Romain Amiot and Christophe Lécuyer and English paleontologist Michael J. Benton noted that Persson's description of Aigialosuchus accorded well with the known material of known contemporary freshwater eusuchians.[10]

In a 2016 paper by Australian paleontologist Benjamin Kear and colleagues, Aigialosuchus was considered to have been a dyrosaurid, not an eusuchian.[11] Aigialosuchus was also classified as a dyrosaurid in a 2018 paper by Swedish paleontologist Elisabeth Einarsson.[6]

Paleoecology

Certain fossils of Aigialosuchus have only been recovered from the Campanian-age deposits in the Kristianstad Basin in Sweden. During the Campanian, the Kristianstad Basin was a subtropical to temperate shallow inland sea home to a diverse marine fauna characteristic of shallow marine life of an inner shelf community and included abundant algae, brachiopods, bryozoans, molluscs (including bivalves, gastropods, belemnites and the ammonites), sea urchins, serpulids, decapods and sponges.[12][13] Additionally, fish (including a vast array of sharks) were also common and fossils of many species of reptiles, most of them marine, have also been found, including mosasaurs, sea turtles, crocodylomorphs and a few dinosaurs.[14]

The fossils of Aigialosuchus described by Persson in 1959 were recovered from marine sediments, though Persson noted that this was not necessarily an indicator that Aigialosuchus itself would have been purely marine. According to Persson, Aigialosuchus could also have lived in the littoral zone or in a river adjacent to the mainland.[2] Within the Kristianstad Basin, the fossil site Ivö Klack has yielded the most Aigialosuchus fossils. Ivö Klack was a small, rocky island during the Cretaceous. The presence of Aigialosuchus at the site might indicate that Aigialosuchus preferred to live in coastal waters, where it could lay its eggs on adjacent land, rest and heat up, similar to modern crocodilians.[15]

Most recent and modern long-snouted crocodylomorphs (notably the gharials) have slender and long teeth, being piscivores. The teeth of Aigialosuchus were stout and short, meaning that it would probably have been adapted to some other form of feeding. According to Einarsson, the robust teeth of Aigialosuchus indicate that it was adapted for feeding on larger fish, such as Enchodus, and larger invertebrates. Contrary to Persson's initial assessment, Aigialosuchus is now believed to have been a marine animal, similar to other dyrosaurids.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Persson 1959, p. 470.

- 1 2 3 4 Persson 1959, p. 471.

- ↑ Adolfssen, Milàn & Friedman 2017, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Schwarz-Wings, Milàn & Gravesen 2014, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Einarsson 2018, p. 37.

- 1 2 Einarsson 2018, p. 28.

- ↑ Persson 1959, pp. 470–471.

- 1 2 3 4 Persson 1959, p. 473.

- ↑ Brochu 2001, p. 566.

- ↑ Martin et al. 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Kear et al. 2016, p. 6.

- ↑ Lindgren 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ Einarsson 2018, p. 27–30.

- ↑ Einarsson 2018, p. 8.

- ↑ Sørensen, Surlyk & Lindgren 2013, p. 90.

Bibliography

- Adolfssen, Jan S.; Milàn, Jesper; Friedman, Matt (2017). "Review of the Danian vertebrate fauna of southern Scandinavia" (PDF). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark. 65: 1–23. doi:10.37570/bgsd-2017-65-01.

- Brochu, Christopher A. (2001). "Crocodylian Snouts in Space and Time: Phylogenetic Approaches Toward Adaptive Radiation". American Zoologist. 41 (3): 564–585. doi:10.1093/icb/41.3.564.

- Einarsson, Elisabeth (2018). "Palaeoenvironments, palaeoecology and palaeobiogeography of Late Cretaceous (Campanian) faunas from the Kristianstad Basin, southern Sweden, with applications for science education". Litholund Theses.

- Kear, Benjamin P.; Lindgren, Johan; Hurum, Jørn H.; Milàn, Jesper; Vajda, Vivi (2016). "An introduction to the Mesozoic biotas of Scandinavia and its Arctic territories" (PDF). Mesozoic Biotas of Scandinavia and Its Arctic Territories. Special Publications of the Geological Society of London. 434 (1): 1–14. Bibcode:2016GSLSP.434....1K. doi:10.1144/SP434.18. S2CID 131680084.

- Lindgren, Johan (1998). "Early Campanian mosasaurs (Reptilia; Mosasauridae) from the Kristianstad Basin, southern Sweden". Dissertations in Geology at Lund University.

- Martin, Jeremy E.; Amiot, Romain; Lécuyer, Christophe; Benton, Michael J. (2014). "Sea surface temperature contributes to marine crocodylomorph evolution" (PDF). Nature Communications. 5: 4658. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4658M. doi:10.1038/ncomms5658. PMID 25130564.

- Persson, Per-Ove (1959). "Reptiles from the Senonian (U. Cret.) of Scania (S. Sweden)" (PDF). Arkiv för Mineralogi och Geologi. 2 (35): 431–519.

- Schwarz-Wings, Daniela; Milàn, Jesper; Gravesen, Palle (2014). "A new eusuchian (Crocodylia) tooth from the Early or Middle Paleocene, with a description of the Early–Middle Paleocene boundary succession at Gemmas Allé, Copenhagen, Denmark" (PDF). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark. 62: 17–26. doi:10.37570/bgsd-2014-62-02.

- Sørensen, Anne Mehlin; Surlyk, Finn; Lindgren, Johan (2013). "Food resources and habitat selection of a diverse vertebrate fauna from the upperlower Campanian of the Kristianstad Basin, southern Sweden". Cretaceous Research. 42: 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.02.002.