| Air campaign of the Uganda–Tanzania War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Uganda–Tanzania War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

600–1,000 personnel |

16 MiG-21s 22 Shenyang J-5s 12 Shenyang J-6s SA-7 and SA-3 teams ~1,000 personnel | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Extremely heavy | Light | ||||||

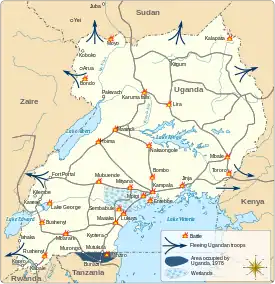

The Uganda–Tanzania War of 1978–79 included an air campaign, as the air forces of Uganda and Tanzania battled for air superiority and launched bombing raids. In general, the conflict was focused on air-to-ground attacks and ground-based anti-aircraft fire; only one dogfight is known to have occurred.

The Uganda Army Air Force dominated the air space during the initial Ugandan invasion of northwestern Tanzania, but achieved little due to bad co-ordination with ground forces and a general lack of planning. At the same time, it suffered increasingly heavy losses as pilots deserted, and the Tanzanian anti-aircraft defenses became more effective. The initiative thus switched to the Tanzania Air Defence Command which supported the country's counter-offensive into Uganda. In the conflict's later stages, the Libyan Arab Republic Air Force intervened on the side of Uganda, but failed to make a tangible impact. The Uganda Army Air Force was eventually destroyed on 7 April 1979 when Tanzanian ground forces overran its main air base at Entebbe. The remaining Ugandan loyalist air pilots subsequently fled the country or joined the Libyan military.

Background to the Uganda–Tanzania War

In 1971 Uganda Army soldiers launched a military coup that overthrew the President of Uganda, Milton Obote, precipitating a deterioration of relations with neighbouring Tanzania.[3] Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere had close ties with Obote and had supported his socialist orientation.[4] Uganda Army Colonel Idi Amin installed himself as President of Uganda and ruled the country under a repressive dictatorship.[3] Nyerere withheld diplomatic recognition of the new government and offered asylum to Obote and his supporters. With the approval of Nyerere, these Ugandan exiles organised a small army of guerillas, and attempted, unsuccessfully, to invade Uganda and remove Amin in 1972. Amin blamed Nyerere for backing and arming his enemies,[5] and retaliated by bombing Tanzanian border towns. Subsequent mediation resulted in the signing of the Mogadishu Agreement, which established a demilitarised zone at the border and required that both countries refrain from supporting opposition forces that targeted each others' governments. Nevertheless, relations between the two presidents remained tense; Nyerere frequently denounced Amin's regime, and Amin made repeated threats to invade Tanzania.[4] Uganda also disputed its border with Tanzania, claiming that the Kagera Salient—a 720-square-mile (1,900 km2) stretch of land between the official border and the Kagera River 18 miles to the south, should be placed under its jurisdiction, maintaining that the river made for a more logical border.[6] The circumstances immediately surrounding the outbreak of the Uganda–Tanzania War in 1978 remain unclear.[7]

Opposing forces

Uganda

.jpg.webp)

The Uganda Army Air Force (UAAF) was established in 1964 with Israeli aid. Its first aircraft was consequently of Israeli origin, and its initial pilots trained in Israel. As Uganda's government forged closer links with the Eastern Bloc, the UAAF began to acquire more aircraft as well as support in training from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Libya. Israeli aid initially continued as well. The UAAF was gradually expanded, and several air bases were built.[8] Following Amin's coup in 1971, the Ugandan military began to deteriorate. International support for Amin's regime eroded over the next years. Israel turned from an ally into an enemy, and the relations with the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia worsened as well though they were not completely severed. The foreign supply of aircraft and spare parts for the UAAF was gradually cut off. As result, it became increasingly difficult to maintain the UAAF's fighters.[9][10] At the same time, tribalism, corruption, and repeated purges negatively affected the military's combat capabilities.[10][11] Furthermore, the Israeli-initiated Operation Entebbe resulted in the destruction of a quarter of the UAAF in 1976;[12][13] Amin's regime subsequently received a substantial number of replacement MiG-21s from the Soviet Union and Libya.[13][10]

By late 1978, the UAAF was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Gore[14] and consisted of at least two dozen MiG-21MFs, MiG-21UMs, MiG-17s,[15] MiG-15UTIs,[16] and L-29s. In addition, several unarmed trainer and transport aircraft were in service,[17][18] including a single Lockheed C-130 Hercules cargo transport.[19] The exact number of Ugandan combat aircraft at the time of the war's outbreak is disputed. Based on reports by Ugandan exiles, journalist Martha Honey estimated that the UAAF consisted of 26 combat aircraft.[20] According to J. Paxton, Uganda possessed 10 MiG-21s, 12 MiG-17s, 2 MiG-15s, and 5 L-29s,[17] while journalist Dominique Lagarde stated that the UAAF consisted of 12 MiG-21s, 10 Mig-17s, 2 MiG-15s, and 12 L-29s.[18] The Soviet ambassador to Uganda claimed that Uganda had 10 MiGs and eight helicopters at the conflict's start.[21] Some of the available aircraft were not combat-ready, however, and were abandoned during the Uganda–Tanzania War without seeing action.[16][18] The lack of spare parts especially affected the Mig-15s and MiG-17s.[22]

The UAAF was split into three fighter squadrons.[22][lower-alpha 2] Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Mukooza commanded the MiG-17 squadron,[23][24] while Lieutenant Colonel Ali Kiiza led the MiG-21 squadron[24] which was called the "Suicide Strike Command", and nicknamed "Sungura".[25] Paxton stated that the UAAF employed about 600 personnel by 1978,[17] while Lagarde claimed that it had 1,000 personnel.[18] In general, the UAAF lacked pilots at the war's start.[26] In addition, the Ugandan military possessed fifty 40mm anti-aircraft guns,[18] man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) and nine radar stations for air defence.[15] A rebel group, the Save Uganda Movement (SUM), later alleged that a number of UAAF members had covertly joined the anti-Amin resistance before the Uganda–Tanzania War; these individuals reportedly helped to sabotage the UAAF's operations from within.[27]

At least some of the Suicide Strike Command's pilots were possibly Libyan-trained Palestinians.[13] The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was known to train pilots for its own air force in Uganda.[28][29] In addition, Pakistani "technicians and air force personnel" reportedly supported Amin's forces during the war with Tanzania.[30] The Soviet Union also loaned air force personnel to Uganda, but the Ugandan Foreign Ministry announced that they were being placed on leave on 30 October 1978, as the conflict with Tanzania began, "to keep them out of the situation that does not concern them".[31]

Tanzania

Tanzania established its air force as the "Air Wing" (Kiswahili: Usafirashaji wa Anga) of the Tanzania People's Defence Force's (TPDF) Air Defence Command in 1965.[32] As it was following an international policy of non-alignment,[33] Tanzania procured aircraft and trainers from a variety of countries, most notably China, Canada,[34] and the Soviet Union.[16] By 1978, the Tanzanian Air Wing possessed 14 MiG-21MFs, two MiG-21UMs, 22 Shenyang J-5s (F-5), 12 Shenyang J-6s (F-6), as well as several transport and trainer aircraft.[16][lower-alpha 3] Furthermore, the country's Air Defence had access to SA-3 surface-to-air missiles,[16] SA-7 MANPADS,[36] 14.5mm and 36mm or 37mm anti-aircraft guns,[18][37] and ground support equipment—including early-warning radars.[16]

The Air Wing was eventually organised into three Kikosi cha Jeshi or KJ Brigades, with each brigade focusing on one particular element of air warfare: aircraft and helicopters (601 KJ), technical support (602 KJ), and air defence (603 KJ). The fighter aircraft unit of 601 KJ, known as "Squadron 601", was based at Mwanza Air Base (MiG-21s) and Ngerengere Air Force Base (F-5s, F-6s).[38] In 1978 the Air Defence Command employed approximately 1,000 personnel.[35][18]

Libya

The Libyan Arab Republic Air Force (LARAF) intervened in the Uganda–Tanzania War's later stages.[39] The LARAF was a large and well-equipped force, though it suffered from limitations in regard to its personnel. Its squadrons were often understrength, and many pilots lacked proper training.[40] Though it is disputed how many and which types of Libyan aircraft were sent to Uganda, the presence of at least two Tupolev Tu-22 bombers was confirmed.[39] LARAF's Tu-22s were operated by the No. 1022 Squadron (also known as "Second Bomber Squadron").[lower-alpha 4] The Libyan Tu-22s were second-hand aircraft imported from the Soviet Union, and suffered from serviceability issues; the bombers were both difficult to maintain and to fly. In addition, Libyan Tu-22 crews were regarded by their Soviet instructors as being subpar, incapable of flying sophisticated bombing missions and more interested in their own safety than carrying out their tasks.[42] The Soviet ambassador to Uganda argued in early March 1979 that the Tu-22 was not suited to a "bush war" in Uganda.[21]

Air campaign

Invasion of Kagera

In early September 1978 the Tanzanians noticed a high volume of Ugandan air reconnaissance flights. By the middle of the month the Ugandan aircraft began crossing into Tanzanian airspace.[43] At this stage, Amin reportedly ordered the UAAF to start bombing Tanzanian targets.[44] SUM member Paul Oryema Opobo claimed that the pilots selected for this mission, Lieutenant David Omita and Lieutenant Sam Walugembe, were supportive of the anti-Amin resistance. Thus, they deliberately launched their bombs at Lake Victoria instead of any Tanzanian settlements.[27][lower-alpha 5] Ugandan troops made their first incursion into Tanzania on 9 October 1978 when a motorised detachment entered a Tanzanian village only to be repulsed by artillery. The next day UAAF MiG fighters bombed forests in the Kagera Salient without effect.[46][47] On 18 October, Ugandan MiGs bombed Bukoba, the capital of the West Lake Region. Despite facing ineffectual Tanzanian anti-aircraft fire, the bombings caused little damage. However, the explosions' reverberations shattered windows and incited the population to panic.[46] On 25 October the Uganda Army attempted to invade northern Tanzania. The ground attack was repulsed by artillery, but UAAF MiGs continued to cross into Tanzanian airspace, where they were again harassed by ineffectual anti-aircraft fire.[48] Ugandan MiGs bombed Bukoba and the Kyaka Bridge—a key crossing over the Kagera River—on 21 and 27 October; most of their bombs hit forests, but one barely missed Bukoba's hospital.[36] The second attack prompted Bukoba's residents to flee the town.[49]

On 27 October, the first Tanzanian reinforcements arrived in the war zone. Among them was a team of six soldiers equipped with SA-7 MANPADS who took up position at Kyaka, and waited for enemy aircraft to enter their range.[36][49] Around this time, the UAAF was ordered to bomb Tanzania's Field Tactical Headquarters at Kapwepwe. The pilots selected for the mission were Omita, Lieutenant Atiku, Lieutenant Abusala, and possibly Walugembe. Flying MiG-21s, they carried out the sortie, but as they returned to Uganda[50] crossed into air space protected by the SA-7 team. The Tanzanians promptly hit the right wing of Omita's plane. He managed to safely eject just before his MiG exploded, and parachuted into a forest. From there, he managed to escape to Mutukula in Uganda.[36][50] Amin's government admitted the loss, but downplayed it by claiming to have shot down several Tanzanian fighters which had allegedly attempted to bomb Ugandan cities.[36] Furthermore, Amin promoted Omita, Atiku, Abusala, and Walugembe to the rank of captain.[50]

On 30 October the Ugandan Army launched a second invasion of northern Tanzania. Tanzanian forces were overwhelmed and quickly withdrew south of the Kagera River.[51][lower-alpha 6] Fearing that the TPDF could stage a counter-attack across the Kyaka Bridge, Ugandan commanders ordered it to be destroyed.[53] The UAAF attacked the crossing from 1 to 3 November; these air strikes either missed or proved ineffective. In contrast, the Tanzanian SA-7 team advanced up to the bridge and reportedly shot down several Ugandan MiGs during these days.[36] After the repeated failures by their air force, the Ugandans finally employed a mining specialist who successfully destroyed the Kyaka Bridge.[47]

Meanwhile, the TPDF's high command decided to redeploy a squadron of F-6s to Mwanza. As the fighters approached the air base on 3 November, however, they entered the air space protected by a Tanzanian SA-3 team as well as anti-aircraft artillery. The latter had not been informed about the redeployment, and mistook the F-6s for enemy fighters, opening fire. One aircraft was hit, and its pilot Ayekuwa Akiirusha was killed. Another fighter diverted from its course and crashed after running out of fuel, though its pilot safely ejected. The other F-6s braved the anti-aircraft fire and successfully landed at Mwanza.[54] A monument was later built in honour of Akiirusha.[55] Several other Tanzanian aircraft, mostly MiGs, were lost due to other accidents during the war.[56]

On 2 November Nyerere declared war on Uganda.[57] After some probes, the TPDF launched a counter-offensive to retake the Kagera Salient on 23 November, encountering little resistance. Four UAAF MiGs carried out air strikes on that day: two bombed the landing strip at Bukoba without causing much damage, while two others were hit by anti-aircraft fire during an attack on Mwanza Air Base. One plane crashed and its pilot, Nobert Atiku, was taken prisoner after ejecting. The other MiG was badly damaged by a SA-7, but its pilot, Ali Kiiza, successfully returned to Entebbe Air Base.[58][lower-alpha 7] MiG-17 squadron commander Andrew Mukooza also flew an attack against targets in northern Tanzania, and was almost shot down by anti-aircraft missiles.[60] One Ugandan aircraft crashed into Lake Victoria after returning to Uganda from an unsuccessful strike in Kagera.[61] The Ugandan government again claimed to have successfully defeated a Tanzanian bombing raid during this time. In fact, no Tanzanian aircraft entered Ugandan air space until 1979.[62]

Disintegration of the Uganda Army Air Force

Following the reconquest of Kagera, the TPDF began to prepare an offensive into Uganda. The UAAF had lost several fighters up to this point, and opted to fly no more attacks into Tanzania. As result, it missed the opportunity to disrupt the assembly of Tanzanian troops as they amassed along the border.[55] Journalist Faustin Mugabe argued that the UAAF's inability to attack Tanzanian territory from this point onwards gave the TPDF the "upper hand in the war".[63] A large-scale Tanzanian artillery bombardment began on 25 December. The UAAF was ordered to respond, but its attacks failed to destroy the Tanzanian artillery. Instead, another Ugandan MiG was shot down by SA-7s in January 1979. The TPDF began its advance into Uganda on 21 January, capturing and destroying the border town of Mutukula. The Tanzanians then constructed an air strip in the locale so transport aircraft could resupply the troops at the front lines.[55]

After an initial rest and further preparations, the Tanzanian forces along with allied Ugandan rebels resumed their offensive.[55] The UAAF continued to attack the Tanzanian-led ground forces and supply bases during this time, while the TPDF's Air Wing began to make its first incursions into Ugandan air space. The most fierce air combat of the war occurred during the Battle of Simba Hills from 11 February 1979. The UAAF repeatedly attacked the TPDF troops at Simba Hills, encountering heavy resistance from SA-7 teams; the TPDF later claimed to have shot down 19 Ugandan aircraft. The Tanzanian Air Wing also bombed Ugandan positions during the battle. After two days of fighting, the Simba Hills fell to the Tanzanian-led forces. The TPDF also captured the Lukoma air strip,[64] which had been used by the UAAF MiGs to stage raids in Tanzanian territory.[65][lower-alpha 8]

Two Ugandan MiG-21s attacked the Lukoma air strip on 14 February in an attempt to destroy Tanzanian transport aircraft. The raid was easily repelled by the TPDF, as Tanzanian MiGs and ground forces responded and forced the Ugandans to flee.[64] On 16 February, the TPDF reportedly shot down a Ugandan MiG-21 that had attacked Mutukula, and claimed to have destroyed two more Ugandan planes during the next day.[67] On 27 February, four UAAF MiG-21s attempted to bomb the Mutukula air strip, but three were reportedly shot down by SA-7s, with one Ugandan pilot taken prisoner.[68] Following its devastating losses during February 1979, the UAAF was effectively eliminated as a fighting force,[69] although it continued to fly missions. In March, the only known dogfight of the war took place, as a Tanzanian fighter shot down a UAAF MiG-21 near Byesika along the Masaka–Mubende road. The Ugandan pilot was killed, while the successful Tanzanian pilot remains unidentified.[68] On 4 March UAAF MiGs were fielded against Ugandan rebels who were conducting a raid on the border town of Tororo, forcing them to retreat into Kenya.[70]

By this point, the UAAF increasingly suffered from the loss of manpower through deaths, defections and desertions. Based on reports by Ugandan exiles, Honey estimated that only six UAAF combat aircraft were still serviceable, while 18 had been shot down and two had been used by defectors to flee the country.[20] The Soviet ambassador to Uganda argued in early March 1979 that only four Ugandan MiGs and two helicopters were left.[21] An Ugandan soldier interviewed by the Drum magazine specified that two pilots had deserted with their MiG-21s.[22] Air force commander Christopher Gore either fled to Sudan[1] or was killed in an ambush,[2] leaving Andrew Mukooza as acting commander of the force.[71] The soldier interviewed by Drum claimed that several pilots suffered from mental breakdowns.[72] Some pilots reportedly refused to fly any longer.[20] One pilot went absent without leave after flying several missions and was arrested and sentenced to death; he was later freed from prison by Tanzanian troops.[73] Kiiza was one of those who deserted during the war's last stages.[lower-alpha 9] Following Kiiza's disappearance, at least some Ugandan soldiers falsely believed that he had been shot down in combat and died.[2] A lack of spare parts and competent mechanics further undermined the UAAF's capabilities,[74] reportedly grounding the remaining MiG-15s and MiG-17s.[22][21]

Libyan intervention and end of the air campaign

.jpg.webp)

Faced with repeated defeats, Amin's regime was in a critical position. In response, its ally Libya intervened in the war during the second half of February, sending an expeditionary force to bolster the Ugandan military.[39] The Libyan Arab Republic Air Force (LARAF) ultimately flew in 4,500 troops as well as armour, artillery, and a substantial amount of supplies.[75] Whether the Libyan force included a substantial number of combat aircraft is unknown.[39] According to the Africa Research Bulletin, "reliable reports" indicated that the Libyans sent six Dassault Mirages and seven MiG-21s to Uganda.[76] Historians Tom Cooper and Adrien Fontanellaz have argued that it is unlikely that Libyan MiG or Dassault Mirage 5 fighters were sent to Uganda, as these short-range aircraft would have been forced to refuel several times to travel to eastern Africa. No such refueling stops for Libyan fighter aircraft were reported. It has been confirmed, however, that two to four Libyan Tupolev Tu-22 bombers deployed to Nakasongola Air Base in early March.[39][lower-alpha 10] According to the German newspaper Der Spiegel, Amin also asked Japan's government to loan him Kamikaze fighters in order to use them against the Tanzanians. The Ugandan President was known for his eccentric and cruel humor, so it is unclear if it was a serious request.[78] According to foreign diplomats based in Kampala, the PLO dispatched 15 pilots to aid Amin during the war, but played no role in the conflict due to a lack of available operational aircraft upon on their arrival.[79]

The remnants of the UAAF, along with the Libyan bombers, flew a number of unsuccessful air strikes during March and early April 1979.[80] On 29 March,[81] "one of the strangest incidents of the war"[69] took place, as Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi ordered one of the Tu-22s to attack Mwanza. This was supposed to intimidate the Tanzanian government into calling off the invasion of Uganda.[77] The Libyan bomber approached over Lake Victoria and aimed at destroying the fuel depot at Mwanza, but completely missed its target;[77][80] its five anti-personnel rockets instead hit the Saa Nane Island Game Sanctuary, slightly injuring one worker and killing six antelopes as well as several birds.[82][lower-alpha 11] Another air strike by the Libyan Tu-22s, aimed at a military base south of the Ugandan-Tanzanian border, was carried out just as poorly. This time the bombs fell close to the town of Nyarubanga in another country, namely Burundi.[80] Following the failed attacks, several Ugandan and Libyan aircraft relocated from Entebbe to the airbases at Nakasongola and Gulu.[81] One Tu-22 operating from Nakasongola conducted regular sorties against Tanzanian forces in southern Uganda.[83]

The Tanzanian Air Wing retaliated by successfully bombing fuel depots at Kampala, Jinja and Tororo on 1 April.[80][81][84] One air strike coincidentally hit and destroyed the Libya-Uganda Development Bank in Jinja.[82] By chance, Amin was in the town at the time, and panicked when the bomb hit. According to eyewitnesses, he ran "into the street screaming incoherently".[80] The destruction of the development bank led many Ugandan soldiers to believe that the Tanzanians had acquired special munitions that could hit select targets on command.[82] Tanzanian MiG-21 jets also raided Entebbe Air Base, strafing the runway and setting part of the terminal ablaze, but ultimately failing to cause enough damage to halt the Libyan air lift in support of Amin's regime.[84][85] Radio Uganda later announced that Amin had said the attacks by the "so-called Tanzanian Air Force...will not escape a very heavy punishment".[86] Radio Uganda also claimed that Amin said that "the bombings do not worry him at all" and repeated that "Nyerere will regret the consequences".[86] The TPDF also attempted to disrupt the Libyan airlift by tricking incoming planes into landing at Mwanza by sending messages to them on Entebbe Air Base's radio frequency. The Tanzanians ended this practice after one attempt, having mistakenly misdirected and seized a Belgian Sabena cargo plane.[87][lower-alpha 12]

After occupying Mpigi, Tanzanian ground forces observed a high level of air traffic at Entebbe Air Base and a large number of troops gathered around it. Their commanders decided to secure it before attacking Kampala to end Libya's support of Uganda and eliminate the hostile forces gathered there.[85] The Tanzanians started an artillery barrage on 6 April, causing Mukooza to flee via helicopter.[60] Lieutenant Colonel Cyril Orambi was left in command of Entebbe Air Base.[89] On the next day, the Battle of Entebbe took place, and resulted in a decisive Tanzanian victory.[90] A dozen UAAF MiG fighters and one Uganda Airlines Boeing 707 were disabled in the attack and left on the runway,[91] while a Libyan C-130 (LARAF C-130H 116) was destroyed by an RPG-7 anti-tank grenade launcher as it attempted to take off.[85][92] Nine or ten fighters were deemed functional enough to be seized as war prizes.[lower-alpha 13] They were flown to Mwanza, but one crashed on landing, killing the pilot. The next morning, 200–365 UAAF personnel led by Orambi surrendered to the TPDF.[93][89] The battle marked the de facto end of the UAAF. Most of its aircraft were destroyed or captured, and the air force personnel that managed to escape to the air fields in Jinja and Nakasongola[96] spread panic among the Ugandan forces there. Mass desertions and defections were the consequence, leaving Mukooza with no means to continue the fight.[71] With Libyan forces having suffered heavily during the battle, Nyerere decided to allow them to flee Kampala and quietly exit the war without further humiliation. He sent a message to Gaddafi explaining his decision, saying that the Libyan troops could be airlifted out of Uganda unopposed from the airstrip in Jinja.[97] Most of them withdrew to Kenya and Ethiopia, where they were repatriated.[98]

Tanzanian jets struck several military installations in Kampala before the ground attack on the Ugandan capital commenced.[99] One Tanzanian fighter was reportedly shot down by Ugandan anti-aircraft fire over Lake Victoria during this time.[78] Several members of the UAAF were captured during the Fall of Kampala on 10–11 April 1979; they were subsequently imprisoned in Bukoba.[100] Nakasongola Air Base was found deserted by Tanzanian forces later that month; they seized Amin's personal Gulfstream executive jet.[101] The UAAF's remaining combat aircraft were seized there and at Gulu.[102] Some Ugandan MiG pilots fled the country;[103] one lieutenant took refuge in Sudan, as did the commander of the UAAF's radar network.[104] Two Ugandan pilots deserted with their aircraft around mid-April, one landing and surrendering with his family at Entebbe, while the other sought refuge at Kilimanjaro International Airport in Tanzania.[105] The leader of the UAAF band, Bonny Kyambadde, was rumoured to have been killed while trying to flee.[106] Mukooza surrendered on 24 April, but was murdered by Ugandan rebels.[60] In contrast, Kiiza was employed by the new Tanzanian-backed Ugandan government.[59] About 30 Ugandan pilots were in the Soviet Union for training when the Uganda–Tanzania War broke out. After Amin's government was overthrown, they opted not to return to Uganda, and instead joined the LARAF.[107] The war ended on 3 June 1979 when Tanzanian ground troops secured the last unoccupied portion of Ugandan territory.[108]

Aftermath and analysis

The UAAF was left completely destroyed by the war. The post-war Ugandan government attempted to rebuild the air force over the immediate following years, but struggled due to lack of funds and only managed to acquire a few helicopters.[109] American journalist John Darnton observed that the war had proven that the UAAF was a "paper tiger".[110] American intelligence analyst Kenneth M. Pollack praised the Libyan airlift in Uganda as an "impressive operation", but criticised Libya's "incompetent" deployment of aircraft in combat and its failure to use aerial reconnaissance.[111]

Renewed internal conflict stymied any efforts to properly restore a Ugandan air force for decades. By 1994, the "Ugandan People's Defence Air Force" still suffered from shortages in equipment and manpower, and was limited to just 100 personnel.[112] Serious efforts at obtaining fixed-wing aircraft were not made until 1999.[113]

Notes

- ↑ Sources differ on Gore's fate, with Ugandan Colonel Rwehururu stating that he fled to Sudan,[1] while another Ugandan soldier claimed that he was killed in an ambush during the Uganda–Tanzania War.[2]

- ↑ According to Lagarde, the UAAF consisted of just two fighter squadrons by 1978.[18]

- ↑ According to Lagarde, the TPDF had 29 combat aircraft in 1979: 11 MiG-21s, 15 MiG-19s, and 3 MiG-17s.[18] According to Paxton, it possessed 12 Shenyang F-8s (MiG-21s), 15 F-6s (MiG-19s), and 3 F-4s (MiG-17s).[35]

- ↑ Some reports indicate the existence of two other LARAF units which were supposed to be equipped with Tu-22s, namely the No. 1110 and No. 1120 Squadrons. According to Tom Cooper and Albert Grandolini, however, these two squadrons were probably never operational.[41]

- ↑ Oryema Opobo stated that the cooperation between SUM and UAAF pilots Omita and Walugembe remained generally unknown until long after the Uganda–Tanzania War; he claimed to have personally met Omita during one SUM covert mission around 1978/79.[45]

- ↑ Ugandan propaganda by the Voice of Kampala claimed that Amin requested the Soviet experts assisting the UAAF to go on leave during this time. In this way, he allegedly wanted to prevent the Soviet Union from becoming entangled in the Uganda–Tanzania War.[52]

- ↑ According to this account, Kiiza was promoted to captain and commander of the Suicide Strike Command after returning to Entebbe.[58] This cannot be the case, however, as Kiiza was already lieutenant colonel and head of the MiG-21 squadron since before the Uganda–Tanzania War.[24] Furthermore, Kiiza stated in an interview that he flew no missions during the war with Tanzania.[59]

- ↑ According to the New Vision, following the capture of Simba Hills, the Ugandans attempted to halt the Tanzanian advance at Kabuwooko with paratroopers, but this failed when the Tanzanians shot their planes down.[66]

- ↑ According to Kiiza, he remained in active service until the Tanzanians encircled Entebbe, whereupon he hid with a friend at Kanyanya in Kampala. When the capital came under attack, they fled to Gayaza.[59]

- ↑ According to Kenneth M. Pollack, just one Tu-22 was deployed to Uganda.[77] The presence of a Tu-22 in Uganda was first confirmed in late March 1979 when a Norwegian photojournalist disguised as a tourist was able to capture an image of one at Entebbe. According to the Africa Research Bulletin, there were rumours that as many as eight Tu-22s were sent to Uganda.[76]

- ↑ According to Kenneth M. Pollack, "a large number of antelope" were killed.[77]

- ↑ The Belgian crew was housed in a hotel for the night and the plane was sent on its way the following day.[87] The incident at Mwanza led to claims that the TPDF had actually successfully seized a Libyan transport aircraft and captured over 100 Libyan soldiers.[88]

- ↑ Avirgan and Honey stated that nine MiG-21s were seized.[93] Cooper wrote that the Tanzanians confiscated two or three MiG-17s and seven MiG-21s.[94] Al J Venter claimed that the TPDF seized 11 MiG-21s. When he asked Tanzanian officers in Kampala about the aircraft, they reportedly responded: "Someone has got to pay for the war".[95]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Rwehururu 2002, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Seftel 2010, p. 231.

- 1 2 Honey, Martha (12 April 1979). "Ugandan Capital Captured". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- 1 2 Roberts 2017, p. 155.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz (2015), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Darnton, John (7 November 1978). "Mediation is Begun in Tanzanian War". The New York Times. p. 5. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ Roberts 2017, p. 156.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 10–18.

- 1 2 3 Brzoska & Pearson 1994, p. 203.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ "1976: Israelis rescue Entebbe hostages". BBC News. British Broadcasting Company. 4 July 1976. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 22.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 50.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Paxton 2016a, p. 1198.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lagarde 1979, p. 8.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 180.

- 1 2 3 Honey, Martha (28 February 1979). "Amin Faces Grave Test As Rebel Threat Grows". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Singh 2012, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Seftel 2010, p. 227.

- ↑ "Libyan troops to blame for Amin's fall". Daily Monitor. 13 April 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Air Force officers (Editorial report)". Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa. No. 5777. BBC Monitoring. 1978.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 19, 22.

- ↑ Roberts 2017, p. 157.

- 1 2 Oryema Opobo 2014, p. 59.

- ↑ Amos 1980, p. 403.

- ↑ Janan Osama al-Salwadi (27 February 2017). "مهمّة "فتح" في أوغندا" [Fatah's mission in Uganda]. Al Akhbar (Lebanon) (in Arabic). Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ↑ "Africa: The President is helpless". Africa. 1979. p. 37.

- ↑ Legum 1980, p. B-438.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 14.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 13.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 14–15.

- 1 2 Paxton 2016b, p. 1169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 25.

- ↑ Legum 1981, p. B-333.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 32.

- ↑ Cooper & Grandolini 2015, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Cooper & Grandolini 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ Cooper & Grandolini 2015, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 53.

- ↑ Oryema Opobo 2014, pp. 59, 97.

- ↑ Oryema Opobo 2014, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 54.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 23.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 3 Mugabe, Faustin (9 October 2017). "Pilot Omita parachutes out of burning MiG-21". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 61.

- ↑ "Air Force experts leaving". Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa. No. 2072. United States Joint Publications Research Service. 1978.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 65.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 29.

- ↑ Cooper 2004, p. 137.

- ↑ Kamazima 2004, p. 167.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Murungi, Paul (8 December 2018). "Gen Kiiza: Chief pilot for six presidents". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 Magembe, Muwonge (15 October 2015). "How Amin's pilot was killed". New Vision. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ Singh 2012, p. 115.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 27.

- ↑ Faustin, Mugabe (31 October 2021). "The 1978 war that pushed Idi Amin out of presidency". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 30.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 79.

- ↑ "When Amin annexed Kagera Salient onto Uganda". New Vision. 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ↑ Honey, Martha (17 February 1979). "Tanzania Reports New Fighting, Claims Ugandan Planes Downed". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 31.

- 1 2 Brzoska & Pearson 1994, p. 207.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 62.

- 1 2 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 36.

- ↑ Seftel 2010, pp. 224, 227.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 151.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 81.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, p. 374.

- 1 2 "Uganda—UR Tanzania : War's New Dimension". Africa Research Bulletin. March 1979. p. 5185.

- 1 2 3 4 Pollack 2004, p. 372.

- 1 2 "Dieser Schlange den Kopf abschlagen" ["Chop off this snake's head"]. Spiegel (in German). 16 April 1979. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ↑ "PLO Did Try to Aid Amin, Despite Denial: Diplomats". Victoria Times. Associated Press. 17 April 1979. p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 "Tanzania Bombs Entebbe Airport, Damaging Runway". The New York Times. 2 April 1979. p. 3. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 120.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 93.

- 1 2 McLain, Lynton; Tonge, David (3 April 1979). "Tanzania jets raid Uganda again". Financial Times. p. 4. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 121.

- 1 2 "Amin's Reaction to Bombing of Entebbe, Kampala and Jinja". Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa. No. 6082–6155. 1979. pp. 9–10. OCLC 378680447.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Kirkham, Norman (1979). "Gaddafi faces bitter protests over 'duped' troops for Amin" (PDF). Enflash. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- 1 2 "Hell in a Tanzanian Prison Camp : Priest Tells a Grisly Tale of Torture". Drum. May 1982. p. 40.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Honey, Martha (11 April 1979). "Entebbe: Tranquility Amid Destruction". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ↑ Cooper 2004, p. 145.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 123.

- ↑ Cooper 2004, p. 142.

- ↑ Venter 1979, p. 58.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 32, 36.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, p. 373.

- ↑ Cooper 2004, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Mugabe, Faustin (22 November 2015). "When Brig Gwanga was taken prisoner of war by Tanzanians". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 181.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 37.

- ↑ Honey, Martha (14 April 1979). "The Fall of Idi Amin: Man on the Run". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ↑ "Uganda: Northern Quagmire". Africa Confidential. Vol. 24. 2 November 1983. pp. 3–5.

- ↑ C.R., Jonathan (19 April 1979). "Tanzanians Renew Offensive in Eastern Uganda". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ Lubega, Henry (3 February 2019). "Politics of Uganda as seen through music since the 50s". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ↑ Abbey, Yunusu (29 April 2013). "Uganda Pilots Fly Libya MIGs". New Vision. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 42.

- ↑ Darnton, John (12 March 1979). "Motives Are Tangled in the War in Uganda". The New York Times. p. A3. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, pp. 374–375.

- ↑ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 52.

- ↑ Kato, Joshua (25 October 2020). "How UPDF grew to become regional force". New Vision. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

Works cited

- Amos, John W. II (1980). Palestinian Resistance: Organization of a Nationalist Movement. New York City: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-025094-7.

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 978-9976-1-0056-3.

- Brzoska, Michael; Pearson, Frederic S. (1994). Arms and Warfare: Escalation, De-escalation, and Negotiation. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872499829.

- Cooper, Tom (2004). African MiGs : MiGs and Sukhois in Service in Sub Saharan Africa. Wien: SHI Publications. ISBN 978-3-200-00088-9.

- Cooper, Tom; Grandolini, Albert (2015). Libyan Air Wars: Part 1: 1973–1985 (online ed.). Havertown: Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1-910777-51-0.

- Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.

- Kamazima, Switbert Rwechungura (2004). Borders, boundaries, peoples, and states : a comparative analysis of post-independence Tanzania-Uganda border regions (PhD). University of Minnesota. OCLC 62698476.

- Lagarde, Dominique (8 March 1979). "Ugandan-Tanzanian war examined. Amin Dada: His War in Tanzania". Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa, No. 2073. United States Joint Publications Research Service. pp. 1–9.

- Legum, Colin, ed. (1980). Africa Contemporary Record: Annual Survey and Documents: 1978–1979. Vol. XI. New York City: Africana Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8419-0160-5.

- Legum, Colin, ed. (1981). Africa Contemporary Record: Annual Survey and Documents: 1979–1980. Vol. XII. New York: Africana Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8419-0160-5.

- Oryema Opobo, Paul (2014). My Role In Removing Idi Amin: Save Uganda Movement. London: Alawi Books. ISBN 978-0992946234.

- Paxton, J., ed. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book 1978-79 (reprint ed.). Springer. ISBN 9780230271074.

- Paxton, J., ed. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book 1979-80 (reprint ed.). Springer. ISBN 9780230271081.

- Pollack, Kenneth Michael (2004). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0686-1.

- Roberts, George (2017). "The Uganda–Tanzania War, the fall of Idi Amin, and the failure of African diplomacy, 1978–1979". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 154–171. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.

- Rwehururu, Bernard (2002). Cross to the Gun. Kampala: Monitor. OCLC 50243051.

- Seftel, Adam, ed. (2010) [1st pub. 1994]. Uganda: The Bloodstained Pearl of Africa and Its Struggle for Peace. From the Pages of Drum. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970-02-036-2.

- Singh, Madanjeet (2012). Culture of the Sepulchre: Idi Amin's Monster Regime. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08573-6.

- Venter, Al J. (October 1979). "The War is over – What next?". Soldier of Fortune. Soldier of Fortune. 4 (10): 58–59, 77, 84–85.