In traditional Albanian culture, Gjakmarrja (English: "blood-taking", i.e. "blood feud") or hakmarrja ("revenge") is the social obligation to kill an offender or a member of their family in order to salvage one's honor. This practice is generally seen as in line with the social code known as the Canon of Lekë Dukagjini (Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit) or simply the Kanun (consisting of 12 books and 1,262 articles[1]). The code was originally a "a non-religious code that was used by Muslims and Christians alike."[2]

Protecting one's honor is an essential component to Albanian culture because it is the core of social respectability. Honor is held in very high regard because it translates over generations. Legacies and history are carried in the family names of Albanians and must be held in high priority, even at the cost of one's life. Therefore, when a personal attack of a formidable magnitude is unleashed on a member of any family, an equal punishment is to be expected by the laws of the Kanun. Some of the actions that initiate gjakmarrja include "killing a guest while he was under the protection of the owner of the house, violation of private property, failure to pay a debt, kidnapping or the seduction or rape of a woman." This often extends many generations if the debt is not paid. Those who choose not to pay with the lives of their family members live in shame and seclusion for the rest of their lives, imprisoned in their homes.[1][3]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

Ottoman period

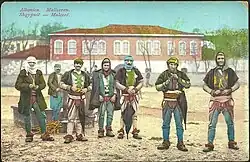

Ottoman control mainly existed in the few urban centres and valleys of northern Albania and was minimal and almost non-existent in the mountains, where Malsors (Albanian highlanders) lived an autonomous existence according to the Kanun (tribal law) of Lek Dukagjini.[4] Disputes would be solved through tribal law within the framework of vendetta or blood feuding and the activity was widespread among the Malsors.[5] In situations of murder tribal law stipulated the principle of koka për kokë ("head for a head") where relatives of the victim are obliged to seek gjakmarrja.[4] Nineteen percent of male deaths in İşkodra vilayet were caused by murders due to vendetta and blood feuding during the late Ottoman period.[5] At the same time Western Kosovo was also an area dominated by the Albanian tribal system where Kosovar Malisors settled disputes among themselves through their mountain law and 600 Albanians died per year from blood feuding.[6]

Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman officials posted to Albanian populated lands, and some Albanians strongly disapproved of blood feuding, viewing it as inhumane, uncivilised and an unnecessary waste of life that created social disruption, lawlessness and economic dislocation.[7] In 1881 local notables and officials from the areas of Debar, Pristina, Elbasan, Mati, Ohrid and Tetovo petitioned the state for the prevention of blood feuds.[8] To resolve disputes and clamp down on the practice the Ottoman state addressed the problem directly by sending Blood Feud Reconciliation Commissions (musalaha-ı dem komisyonları) that produced results with limited success.[9] In the late Ottoman period, due to the influence of Catholic Franciscan priests some changes to blood feuding practices occurred among Albanian highlanders such as guilt being restricted to the offender or their household and even one tribe accepting the razing of the offender's home as compensation for the offense.[9]

In the aftermath of the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 the new Young Turk government established the Commissions for the Reconciliation of Blood Feuds that focused on the regions of İpek (Pejë), Prizren and Tepedelen (Tepelenë).[10] The commissions sentenced Albanians who had participated in blood feud killing and the Council of Ministers allowed them to continue their work in the provinces until May 1909.[10] After the Young Turk Revolution and subsequent restoration of the Ottoman constitution, the Shala, Kastrati, Shoshi and Hoti tribes made a besa (pledge) to support the document and to stop blood feuding with other tribes until 6 November 1908.[11]

Independent Albania

As of 1940, about 600 blood feuds reportedly existed against King Zog I of the Albanians.[12] There has been a revival of instances of gjakmarrja in remote parts of Albania (such as the north) and Kosovo due to the lack of state control since the collapse of communism.[13][14] The Albanian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights considers one reason for the pervasiveness of blood feuds to be the malfunction of the country's judiciary. Many Albanians see the courts as corrupt or ineffective, and prefer the perceived self-government offered by adherence to the Kanun, alongside state law.[14][2]

An Albanian study of 2018 on blood feuds that included data from police records noted that there are 704 families affected with 591 in Albania and 113 having left the country.[15] Six Albanian districts, Kukës, Shkodër, Lezhë, Tiranë and Durrës, are affected by the practice.[15] Shkodër and Lezhë districts are most affected and the cities of Tiranë and Durrës are least affected.[15] In Tiranë blood feuds arrived to the capital city with the migration of people from the north and north-eastern regions.[15] Families engaged in blood feuds mainly live in poverty due to isolation and inability to access better living conditions.[15]

Ismet Elezi, a professor of law at the University of Tirana, believes that in spite of the Kanun's endorsement of blood vengeance, there are strict rules on how the practice may be carried out. For instance, revenge killings of women (including male-role-filling sworn virgins), children, and elderly persons are banned.[14] Others believe that the Kanun itself emphasises reconciliation and the peacemaking process, and that selective interpretation of its rules is responsible for the current bloodshed.[13] For instance, in recent years, there are more and more reports of women and children being subjected to the same redemption murders.[2] These forgotten rules breed misinterpretation of the Kanun and encourage the mindless killings of family members.[2]

Kosovo

In Kosovo, most cases of Gjakmarrja were reconciled in the early 1990s in the course of a large-scale reconciliation movement to end blood feuds led by Anton Çetta.[16] The largest reconciliation gathering took place at Verrat e Llukës on 1 May 1990, which had between 100,000 and 500,000 participants. By 1992 the reconciliation campaign ended at least 1,200 deadly blood feuds, and in 1993 not a single homicide occurred in Kosovo.[16]

Montenegro

In Montenegro, an event "Beslidhja e Malësisë" (Pledge of Malësia) took place in Tuzi (28 June 1970) in the presence of Catholic and Muslim clergy.[17] Families and other extended kin in the Malesia region made a besa and agreed to cease blood feuding and accept state judicial outcomes for victims and perpetrators.[17]

Cultural references

Albanian writer Ismail Kadare considers gjakmarrja to be not an exclusively Albanian phenomenon, but one historically characteristic of the Balkans as a whole.[18] His 1980 novel Broken April (Albanian: Prilli i Thyer) explores the social effects of an ancestral blood feud between two landowning families, in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s.[19][20][21] The New York Times, reviewing it, wrote: "Broken April is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country. You know it must happen because that is the way life is lived in these mountains. Insults must be avenged; family honor must be upheld...."[22]

A 2001 Brazilian film adaptation of the novel titled Behind the Sun (Portuguese: Abril Despedaçado) transferred the action from rural Albania to the 1910 Brazilian badlands, but left the themes otherwise untouched. It was made by filmmaker Walter Salles, starred Rodrigo Santoro, and was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[23] The American-Albanian film The Forgiveness of Blood also deals with the consequences of a blood feud on a family in a remote area of modern-day Albania.[13]

See also

- Blood feud

- Eye for an eye

- Krvna osveta - the equivalent cultural practice among South Slavic peoples

- Reconciliation Movement in 1990

- Sippenhaft - similar practices among Germans

- Gjarpinjt e gjakut

References

- 1 2 Mattei, Vincenzo. "Albania: The dark shadow of tradition and blood feuds". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- 1 2 3 4 "Albania: Blood Feuds -- Forgotten Rules Imperil Everyone (Part 3)". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ↑ Kasapi, Andrew Hosken and Albana (2017-11-12). "The children trapped by Albania's blood feuds". Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 30.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 30, 34–35.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 29, 118–121, 138, 209.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, p. 122.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 119.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, p. 161.

- ↑ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 159. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. Harper & Brothers. p. 468.

- 1 2 3 Freeman, Colin (1 July 2010). "Albania's modern-day blood feuds". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Naegele, Jolyon (12 October 2001). "Albania: Blood Feuds – 'Blood For Blood'". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Blood feuds still affect a number of Albanian families". Tirana Times. 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 Marsavelski, Aleksandar; Sheremeti, Furtuna; Braithwaite, John (2018). "Did Nonviolent Resistance Fail in Kosovo?" (PDF). The British Journal of Criminology. 58: 218–236. doi:10.1093/bjc/azx002.

- 1 2 Kajosevic, Samir (29 June 2020). "Montenegro Albanians Take Pride in Abandoning Ancient Blood Feuds". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ↑ Kadare, Ismail. "This Blood Feud with Kalashnikov is Barbarian". Komiteti i Pajtimit Mbarëkombëtar (Committee of Nationwide Reconciliation). Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "Albanian Revenge". Christian Science Monitor. 24 October 1990.

- ↑ David Bellos (15 December 2020). "Why Should We Read Ismail Kadare?". World Literature Today.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Ismail Kadare". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015.

- ↑ Mitgang, Herbert (12 December 1990). "Books of The Times; An Albanian Tale of Ineluctable Vengeance". The New York Times.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave (21 December 2001). "AT THE MOVIES". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Gellçi, Diana (2005). Gjakmarrja: Albanian Highlander's [sic] "Blood Feud" as Social Obligation. Tirana: Albanian Institute for International Studies. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

External links

- Republic of Albania Country Report published by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, United Kingdom

- Graham, Adam H (9 January 2015). "Blood feuds in Albania's Accursed Mountains". BBC.