Albert Gallatin Jenkins | |

|---|---|

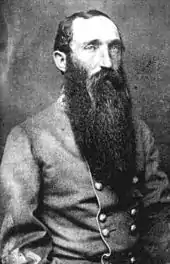

An 1859 photograph of Jenkins | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 11th district | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | John S. Carlile |

| Succeeded by | John S. Carlile |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 10, 1830 Cabell County, Virginia (now West Virginia) |

| Died | May 21, 1864 (aged 33) Battle of Cloyd's Mountain (Pulaski County, Virginia) |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | Brigadier general |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Albert Gallatin Jenkins (November 10, 1830 – May 21, 1864) was an American attorney, planter, politician and military officer who fought for the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He served in the United States Congress and later the First Confederate Congress. After Virginia's secession from the Union, Jenkins raised a company of partisan rangers and rose to become a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army, commanding a brigade of cavalry. Wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg and again during the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain, during which he was captured, Jenkins died just 12 days after his arm was amputated by Union Army surgeons as he was unable to recover. His former home is now operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Early and family life

Jenkins was born to the wealthy plantation owner Capt. William Jenkins and his wife Jeanette Grigsby McNutt in Cabell County, in what was then Virginia. After a private education suitable for his class, he attended Marshall Academy when he was fifteen. He graduated from Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, in 1848 and from Harvard Law School in 1850.

Early career

Admitted to the Virginia bar the same year, Jenkins practiced in Charleston. In 1859, he inherited part of his father's sprawling slave plantation.[1] He was named a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati in 1856, and was elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth United States Congresses.

Civil War

With the outbreak of the Civil War and Virginia's subsequent secession, Jenkins resigned from Congress in early 1861. He raised a company of mounted partisan rangers, which by June was enrolled in the Confederate Army as a part of the 8th Virginia Cavalry, with Jenkins as its colonel. By the year's end, his men had become such a nuisance to the Federals in western Virginia that military governor Francis H. Pierpont appealed to President Abraham Lincoln to send in a strong leader to stamp out the rebellion in the area. Early in 1862, Jenkins was elected as a delegate to the First Confederate Congress. After promotion to brigadier general on August 1, 1862, he returned to active duty. Throughout the fall, his men harassed Union troops and supply lines, including the vital Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. In September, Jenkins's cavalry raided northern Kentucky and now West Virginia. They briefly entered extreme southern Ohio across from Ravenswood, West Virginia, becoming one of the first organized Confederate units to enter a Northern state. In December, Robert E. Lee requested that Jenkins and his men transfer to the Shenandoah Valley.

After spending the winter foraging for supplies, he led his men on a raid in March 1863 through western Virginia, seeking to influence the popular vote which ultimately created the state of West Virginia. During the Gettysburg campaign, Jenkins' brigade formed the cavalry screen for Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps. Jenkins led his men through the Cumberland Valley into Pennsylvania and seized Chambersburg, burning down nearby railroad structures and bridges. During their invasion of Pennsylvania, his brigade, under Jenkins' direction, abducted hundreds of African Americans (most of them free people of color with a few being fugitive slaves), all of whom were forcibly sent southwards and sold into slavery.[2]

He accompanied Ewell's column to Carlisle, briefly skirmishing with Union militia at the Battle of Sporting Hill near Harrisburg. During the subsequent Battle of Gettysburg, Jenkins was wounded on July 2 and missed the rest of the fighting. Jenkins did not recover sufficiently to rejoin his command until fall, and spent the early part of 1864 raising and organizing a large cavalry force for service in western Virginia. By May, he had been appointed Commander of the Department of Western Virginia with his headquarters at Dublin. Hearing that Union Brig. Gen. George Crook had been dispatched from the Kanawha Valley with a large force, Jenkins took the field to contest the Federal arrival. On May 9, 1864, he was severely wounded and captured during the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain, a Union victory which destroyed the last railroad line connecting Tennessee and Virginia.

Death and legacy

A Union surgeon amputated Jenkins' arm, but he never recovered, dying twelve days later. He was initially buried in New Dublin Presbyterian Cemetery. After the war, his remains were reinterred at his home in Greenbottom, near Huntington, West Virginia. He was later reinterred in the Confederate plot in Spring Hill Cemetery in Huntington.

Jenkins's home, Green Bottom, is now operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In 1937, Marshall University constructed Jenkins Hall, naming it in honor of the Confederate cavalry officer. In 2018, the university reviewed the name given Jenkins’ history as a slaveholder and staunch defender of slavery. They chose to keep the name while contextualizing the history of racism and slavery.[3] On July 7, 2020, the Marshall University Board of Governors voted unanimously to remove the name from its education building.[4]

In 2005, a monument to General Jenkins was erected in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, commemorating his service during the Gettysburg Campaign.[5] In the summer of 2020, the monument was removed.[6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Weil, Julie Zauzmer; Blanco, Adrian; Dominguez, Leo (20 January 2022). "More than 1,700 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation". Washington Post. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ "The Confederate "Slave Hunt" and the Gettysburg Campaign". 6 May 2020.

- ↑ Stuck, Taylor (24 February 2019) [Originally published 22 February 2019]. "MU board chooses to keep Jenkins Hall name". The Herald-Dispatch. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ "Board of Governors votes to remove name from campus building" (Press release). Marshall University. 7 July 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ "Monuments Dedicated!" (PDF). The Bugle. Vol. 15, no. 2. Camp Curtin Historical Society and Civil War Round Table, Inc. Summer 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16.

- ↑ Dickinson College History Course 288 page, citing Harrisburg Patriot-News coverage (July 3, 2020), accessed March 25, 2023.

References

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Evans, Clement A., ed. Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History. 12 vols. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. OCLC 833588.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.