The album era was a period in English-language popular music from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s in which the album was the dominant form of recorded music expression and consumption.[1][2] It was primarily driven by three successive music recording formats: the 33⅓ rpm long-playing record (LP), the cassette tape, and the compact disc (CD). Rock musicians from the US and the UK were often at the forefront of the era, which is sometimes called the album-rock era in reference to their sphere of influence and activity. The term "album era" is also used to refer to the marketing and aesthetic period surrounding a recording artist's album release.

LP albums developed in the early 20th century and were originally marketed for classical music and wealthier adult consumers. However, singles still dominated the music industry, eventually through the success of rock and roll performers in the 1950s, when the LP format was utilized more for soundtrack, jazz, and some pop recordings. It was not until the mid-1960s, when the Beatles began to release artistically ambitious and top-selling LPs, that more rock and pop acts followed suit and the industry embraced albums to immense success while burgeoning rock criticism validated their cultural value. By the next decade, the LP had emerged as a fundamental artistic unit and a widely popular item with young people, often marketed using the idea of a concept album, which was employed especially by progressive musicians in both rock and soul.

At the end of the 1970s, LP albums experienced a decline in sales while the singles format was reemphasized by the developments of punk rock, disco, and MTV's music video programming. The record industry combatted this trend by gradually displacing LPs with CDs, releasing fewer singles that were hits to force sales of their accompanying albums, and inflating the prices of CD albums over the next two decades, when their production proliferated. The success of major pop stars led to the development of an extended rollout model among record labels, marketing an album around a catchy lead single, an attention-grabbing music video, novel merchandise, media coverage, and a supporting concert tour. Women and black musicians continued to gain critical recognition among the album era's predominantly white-male and rock-oriented canon, with the burgeoning hip hop genre developing album-based standards in its own right. In the 1990s, the music industry saw an alternative rock and country music boom, leading to a revenue peak of $15 billion in 1999 based in CD sales. However, the development of file sharing networks such as Napster began to undermine the format's viability, as consumers were able to rip and share CD tracks digitally over the Internet.

In the early 21st century, music downloading and streaming services emerged as popular means of distribution, as album sales suffered a steep decline and recording acts generally focused on singles, effectively ending the album era. The critical paradigm also shifted away from rock and toward more innovative works being produced in pop and urban music, which dominated record sales in the 2000s. High-profile pop acts continued to market their albums seriously, with surprise releases emerging as a popular strategy. While physical music sales declined further worldwide, the CD remained popular in some countries such as Japan, due in part to the marketing and fandom surrounding top-selling Japanese idol performers, whose success represented a growing shift away from the global dominance of major English-language acts. By the end of the 2010s, concept albums had reemerged with culturally relevant and critically successful personal narratives. Meanwhile, pop and rap artists garnered the most album streams with minimal marketing that capitalized on the digital era's on-demand consumer culture, which evolved even more rapidly during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the music industry.

Pre-history

Technological developments in the early 20th century led to sweeping changes in the way recorded music was made and sold. Prior to the LP, the standard medium for recorded music had been the 78 rpm gramophone record, made from shellac and featuring a three-to-five minute capacity per side.[3] The capacity limitations placed constraints on the composing processes of recording artists, while the fragility of shellac prompted the packaging of these records in empty booklets resembling photo albums,[3] with typically brown-colored wrapping paper as covers.[4] The introduction of polyvinyl chloride in record production led to vinyl records, which played with less noise and more durability.[3]

In the 1940s, the market for commercial- and home-use recordings was dominated by the competing RCA Victor and Columbia Records, whose chief engineer Peter Carl Goldmark pioneered the development of the 12-inch long play (LP) vinyl record.[3] This format could hold recordings as long as 52 minutes, or 26 minutes per side,[5] at a speed of 33⅓ rpm, and was playable with a small-tipped "microgroove" stylus designed for home playback systems.[3] Officially introduced in 1948 by Columbia, LPs became known as "record albums", termed in reference to the photo album-like 78 packaging.[3] Another innovation from Columbia was the addition of graphic and typographic design to album jacket covers, introduced by Alex Steinweiss, the label's art director. Encouraged by its positive effect on LP sales, the music industry adopted illustrated album covers as a standard by the 1950s.[4]

.jpg.webp)

Originally, the album was primarily marketed for classical music listeners,[6] and the first LP released was Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor for Violin and Orchestra Op. 64 (1948) by Nathan Milstein and the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York under Bruno Walter.[7] Film soundtracks, Broadway show cast recordings, jazz musicians, and some pop singers such as Frank Sinatra soon utilized the new longer format. Jazz artists especially, such as Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, and Dave Brubeck, preferred the LP for how its capacity allowed them to record their compositions with concert-length arrangements and improvisations.[7] The original Broadway cast recording of the musical Kiss Me, Kate (1949) sold 100,000 copies in its first month of release and, together with South Pacific (which topped the album charts for 63 weeks), brought more attention to LPs, while the Broadway cast recording of My Fair Lady became the first LP to sell one million copies.[8][9] However, in the 1950s and into the 1960s, 45 rpm seven-inch single sales were still considered the primary market for the music industry, and albums remained a secondary market. The careers of notable rock and roll performers such as Elvis Presley were driven primarily by single sales.[6]

1960s: Beginnings in the rock era

Concept albums and Rubber Soul (1964–1966)

The arrival of the Beatles in the US in 1964 is credited by music writers Ann Powers and Joel Whitburn as heralding the "classic album era"[10] or "rock album era".[11] In his Concise Dictionary of Popular Culture, Marcel Danesi comments that "the album became a key aspect of the countercultural movement of the 1960s, with its musical, aesthetic, and political themes. From this, the 'concept album' emerged, with the era being called the 'album era'".[12] According to media academic Roy Shuker, with the development of the concept album in the 1960s, "the album changed from a collection of heterogeneous songs into a narrative work with a single theme, in which individual songs segue into one another", "unified by a theme, which can be instrumental, compositional, narrative, or lyrical".[13]

Conversely, popular culture historian Jim Cullen says the concept album is "sometimes [erroneously] assumed to be a product of the rock era",[14] with The A.V. Club writer Noel Murray arguing that Sinatra's 1950s LPs, such as In the Wee Small Hours (1955), had pioneered the form earlier with their "thematically linked songs".[15] Similarly, Will Friedwald observes that Ray Charles had also released thematically unified albums at the turn of the 1960s that made him a major LP artist in R&B, peaking in 1962 with the high-selling Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music.[16] Some place the birth of the format even earlier, with journalist David Browne referring to Woody Guthrie's 1940 album Dust Bowl Ballads as "likely one of the first concept albums in music history".[17]

The track listings on these antecedents, however, typically consisted of material that was not written by the artist (with the exception of Guthrie).[18] With their hot rod-themed 1963 release Little Deuce Coupe, the Beach Boys became the first act to release a concept album that consisted almost entirely of original songwriting.[18] In his 2006 book American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MP3, academic Larry Starr credits the Beach Boys' 1964 concept albums Shut Down Volume 2 and All Summer Long with marking "the beginnings of ... the increasing importance of album tracks, and eventually of albums themselves".[19] Music journalist Gary Graff points to Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (released in August 1965) as another possible starting point to the album era, as it constituted "a cohesive and conceptual body of work rather than just some hit singles ... with filler tracks."[20]

Danesi cites the Beatles' December 1965 release Rubber Soul as one of the era's first concept albums.[12] According to music historian Bill Martin, Rubber Soul was the "turning point" for popular music, in that for the first time "the album rather than the song became the basic unit of artistic production."[21] Author David Howard agrees, saying that "pop's stakes had been raised into the stratosphere" by Rubber Soul and that "suddenly, it was more about making a great album without filler than a great single."[22] In January 1966, Billboard magazine referred to the opening sales of Rubber Soul in the US (1.2 million copies over nine days) as proof of teenage record-buyers gravitating towards the LP format.[23] While it was in keeping with the industry norm in the UK, the lack of a hit single on Rubber Soul added to the album's identity in the US as a self-contained artistic statement.[24][25]

Following the Beatles' example, several rock albums intended as artistic statements were released in 1966, including the Rolling Stones' Aftermath, the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, Dylan's Blonde on Blonde, the Beatles' own Revolver, and the Who's A Quick One.[26][nb 1] Music journalist Mat Snow cites these five releases, together with Otis Redding's 1965 LP Otis Blue, as evidence that "the album era was here, and though hit singles still mattered, they were no longer pop's most important money spinners and artistic statements."[27] According to Jon Pareles, the music industry profited immensely and redefined its economic identity because of the era's rock musicians, who "started to see themselves as something more than suppliers of ephemeral hit singles".[28] In the case of the British music industry, the commercial success of Rubber Soul and Aftermath foiled attempts to re-establish the LP market as the domain of wealthier, adult record-buyers. From early 1966, record companies there ceased their policy of promoting adult-oriented entertainers over rock acts, and embraced budget albums for their lower-selling artists to cater to the increased demand for LPs.[26]

Post-Sgt. Pepper (1967–1969)

The Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is identified by Rolling Stone assistant editor Andy Greene as marking "the beginning of the album era",[29] a reference echoed by Scott Plagenhoef of Pitchfork;[30] Greene adds that "it was the big bang of albums".[29] Chuck Eddy refers to the "high album era" as beginning with Sgt. Pepper.[31] Its release in May 1967 coincided with the emergence of dedicated rock criticism in the US and intellectuals seeking to position pop albums as valid cultural works.[32] Music historian Simon Philo writes that, aside from the level of critical acclaim it received, "the record's [commercial] success ushered in the era of album-oriented rock, radically reshaping how pop music worked economically."[33] Reinforcing its creative ambition, Sgt. Pepper was packaged in a gatefold sleeve with a lyric sheet, typifying a trend whereby musicians now commissioned associates from the art world to design their LP sleeves and presented their albums to the record company for release.[25] Greg Kot said Sgt. Pepper introduced a template for both producing album-oriented rock and consuming it, "with listeners no longer twisting the night away to an assortment of three-minute singles, but losing themselves in a succession of 20-minute album sides, taking a journey led by the artist."[34] Because of its cohesive musical aesthetic, it is often regarded as a concept album.[13]

The classic album era begins around this time and it canonizes music in a very different way than when you hear a single. And that's a powerful reason why the music remains so resonant, because the album is a like a novel set to music. It's the form we share with our children and the form we teach and the form we collect.

— Ann Powers (2017)[35]

Spearheaded by Sgt. Pepper, 1967 saw a greater output of artistically innovative and renowned rock albums from flourishing music scenes in both the US and the UK. These were often accompanied by popular singles and included the Stones' Between the Buttons (with the two-sided single "Ruby Tuesday"/"Let's Spend the Night Together"), Cream's Disraeli Gears (featuring the band's most well-known song "Sunshine of Your Love"), and the Who's The Who Sell Out, which included hits like "I Can See for Miles" in the framework of a concept album satirizing commercialism and radio.[35] Meanwhile, Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze" (1967) was released as the "debut single of the Album Rock Era", according to Dave Marsh.[36] Danesi cites the Beatles' 1968 White Album alongside Sgt. Pepper as part of the era's emergence.[12] Shuker cites We're Only in It for the Money (1967) by the Mothers of Invention and Arthur, or Decline of the British Empire (1969) by the Kinks as subsequent concept albums, while noting a subset of the form in rock operas such as Pretty Things' S.F. Sorrow (1968) and the Who's Tommy (1969).[13]

According to Neil Strauss, the "album-rock era" began in the late 1960s and ultimately encompassed LP records by both rock and non-rock artists.[37] According to Ron Wynn, the singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Isaac Hayes helped bring soul music into "the concept album era" with his 1969 album Hot Buttered Soul, which succeeded commercially and introduced more experimental structures and arrangements to the genre.[38] Also among soul singers, Robert Christgau cites Redding as one of the genre's "few reliable long-form artists" (with Otis Blue being his "first great album"),[39] as well as Aretha Franklin and her series of four "classic" LPs for Atlantic Records, from I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You (1967) to Aretha Now (1968), which he says established an "aesthetic standard" of "rhythmic stomp and catchy songs". This series is compared by Christgau to similarly "prolific" runs from the Beatles, the Stones, and Dylan in the same decade, as well as subsequent runs by Al Green and Parliament-Funkadelic.[40] The Rolling Stones' four-album run beginning in the late 1960s with Beggars Banquet (1968) and Let It Bleed (1969) – and concluding with Sticky Fingers (1971) and Exile on Main St. (1972) – is also highly regarded, with the cultural historian Jack Hamilton calling it "one of the great sustained creative peaks in all of popular music".[41]

1970s: Golden age of the LP

The period from the mid 1960s to the late 1970s was the era of the LP and the "golden era" of the album. According to BBC Four's When Albums Ruled the World (2013), "These were the years when the music industry exploded to become bigger than Hollywood."[42] "The album era had ushered in the notion of the rock singer as an artist who is worth paying attention to for more than the length of a hit", Pareles later observed. "Performers could become vivid presences to their fans even when they weren't ubiquitous on the Top 40, and loyalties were formed that continue[d] to the [1990s] for some performers of the 1960s and 1970s, from the Kinks to Michael Jackson to Sting."[43] Among those who emerged in the 1970s was Bruce Springsteen, whom Powers calls "the quintessential album-era rock star" for how he "used the long-player form itself more powerfully over the arc of a career, not only to establish a world through song, but to inhabit an enduring persona".[44]

Progressive rock and soul musicians utilized highly conceptual album-oriented approaches in the 1970s.[45] Pink Floyd released thematically conceptual and intricately produced LPs that reinvented standards in rock through the next decade, particularly with their 1973 album The Dark Side of the Moon.[46] The musician-producer Brian Eno emerged through prolific work that thoroughly utilized the format with progressively experimental approaches to rock, peaking throughout the album era with his solo recordings as well as albums produced for Roxy Music, David Bowie, Talking Heads, and U2.[47] Under Berry Gordy's leadership at the soul label Motown, the singer-songwriters Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder were given creative control to approach their albums more seriously in what had generally been a single-focused genre, leading to a series of innovative LPs from the two as the decade ensued.[48] For their innovative work, Gaye and Wonder were the few exceptions in what Marc Hogan of Pitchfork observes would become a predominantly white-male "rock-stuffed canon" during the album era, one that largely excluded works by female and African-American musicians.[49]

According to Eric Olsen, Pink Floyd was "the most eccentric and experimental multi-platinum band of the album rock era", while the reggae artist Bob Marley was "the only towering figure of the rock era not from America or the U.K."[50] The 1970 Joni Mitchell LP Ladies of the Canyon is commonly regarded as one of the album era's most important records.[51] The productions of Bob Ezrin – who worked on 1970s albums by Alice Cooper and Kiss' Destroyer (1976) – are also highlighted from this era. As music journalist James Campion writes, "The 1970s album era was perfectly suited to his cinematic approach. Its format, with its two sides, as if two acts in a play with an intermission, allows for a crucial arc in the storytelling."[52] Along with the LP record, the 8-track tape was another format popular in the US in this period.[42]

Elaborating on the 1970s LP aesthetic, Campion identifies cultural and environmental factors that, in his mind, made the format ideal for young people during the decade. He describes the "solitary ambience" offered to listeners by the turntable and headphones, which "enveloped [them] in intricate stereo panning, atmospheric sounds, and multilayered vocal trickery".[52] Warren Zanes regards the shrewd sequencing of LP tracks as "the album era's most under-recognized art".[53] The popularity of recreational drugs and mood lamps at the time provided further settings for more focused listening experiences, as Campion notes: "This kept the listener rapt to each song: how one flowed into the other, their connecting lyrical content, and the melding of instrumentation."[52]

.jpg.webp)

In comparison to future generations, Campion explains that people growing up in the 1970s found greater value in album listening, in part because of their limited access to any other home entertainment appliance: "Many of them were unable to control the family television or even the kitchen radio. This led to prioritizing of the bedroom or upstairs den". Campion describes this setting as an "imagination capsule" for the era's listeners, who "locked away inside the headphone dreamscape, studying every corner of the 12-inch artwork and delving deeper into lyrical subtext, whether in ways intended by the artist or not". Other cultural influences of the time also informed the listening experiences, according to Campion, who cites the horror and science fiction fantasies and imagery of comic books, as well as advertising, propaganda, and "the American promise of grandeur". In his analysis, Campion concludes: "As if sitting in their own theater of the mind ... they were willing participants in the playful meandering of their rock-and-roll heroes."[52] Adding to this observation, Pareles says, "Successive songs become a kind of narrative, held together by the image of and fantasies about the performer." As "listeners' affection and fascination ... transferred from a hit song, or a string of hits, to the singer", particularly successful recording artists developed a "staying power" among audiences, according to Pareles.[43]

Judgments were simpler in pop's early days partly because rock and roll was designed to be consumed in three-minute take-it-or-leave-it segments. The rise of the LP as a form – as an artistic entity, as they used to say – has complicated how we perceive and remember what was once the most evanescent of the arts. The album may prove a '70s totem – briefer configurations were making a comeback by decade's end. But for the '70s it will remain the basic musical unit.

— Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981)[54]

According to Hogan, with Sgt. Pepper having provided the impetus, the idea of a "concept album" became a marketing tool by the 1970s, as "no shortage of bands used the pretense of 'art' to sell tens of millions of records." Citing hugely successful albums like The Dark Side of the Moon for leading the trend, Hogan says "record sales spiraled upward" through the mid 1970s.[49] In 1974, "dollar sales of records and tapes in the United States reached an all-time high of $2.2 billion", according to the World Book Encyclopedia, with pop and rock recordings making up two-thirds of all recorded music sales. However, the book attributes this partly to an increase in record prices over the year, while estimating the actual number of net LP sales had decreased from 280 million to 276 million copies and noting an increase in tape sales from 108 million to 114 million. As record companies concentrated their efforts toward pop and rock, releases in other genres like classical, jazz, and easy listening were marginalized in the market. Many jazz artists during this period recorded crossover LPs with pop-friendly songs in order to increase their record sales.[55]

By 1977, album sales had begun "ticking downward", according to Hogan.[49] Pareles attributes this decline to the developments of punk rock and disco in the late 1970s: "Punk returned the focus to the short and noisy song. Disco concentrated on the physical moment when a song makes a body move."[43] Christgau similarly notes that "the singles aesthetic began to reassert itself with disco and punk", suggesting this ended the "High Album Era".[56] In a different analysis, historian Matthew Restall observes in this period popular acts struggling to sustain the high level of success afforded to their previous albums. Citing the disappointing receptions of Elton John's Blue Moves (1976) and Fleetwood Mac's Tusk (1979), Restall says, "[These] are dramatic examples of how the recording artists of the great album era ... suffered the receiving end of a horizon of expectations."[57]

1980s–1990s: Competing formats, marketing tactics

Decline of LP records and other cultural shifts (1979–1987)

The fall of LP record sales at the end of the 1970s marked the end of the LP-driven "golden age",[42] as the music industry faced competition from a commercial resurgence in the film industry and the popularity of arcade video games.[49] The success of MTV's music video programming also reemphasized the single format in the 1980s and early 1990s. According to Pareles, it soon became apparent that, "after the album-rock era of the 1970s, MTV helped return the hit single to prominence as a pop marketing tool" and influenced record buyers' consuming habits toward more "disposable hits".[43]

Pop stars of the 1980s, such as Michael Jackson and Madonna, were able to galvanize interest in their albums by releasing a single or music video to MTV. This led to the development of the modern album launch, intended to drive an album's marketing momentum for an extended period of time, ranging from many weeks and months to more than a year. "Over time, there became an unspoken (and, eventually, baked into the budget) checklist to releasing a major-label pop album", writes Vulture journalist Justin Curto, who cites elements in this model to be an upbeat lead single, an attention-grabbing music video, press coverage, novel merchandise, and the announcement of a supporting concert tour.[58] Dependent on outlets like MTV that exclusively played hit songs, record companies placed more pressure on recording acts to achieve instant commercial success and marketability. "The 1980s and 1990 brought record sales to new peaks while the performers themselves tended to flash and burn out", as Pareles chronicles.[43]

At the turn of the 1980s, critics initially struggled to reconcile the rise of punk singles in their conceptions of the hierarchical LP canon. However, The Clash's London Calling (1979) and other punk LPs soon earned recognition in rankings of the greatest albums. As the decade ensued, Prince, Kate Bush, and Public Enemy emerged as further exceptions in the predominantly white-male and rock-oriented canon of the album era.[49] Hip hop artists also achieved a corresponding critical stature through a series of successful albums later in the decade. Starting with the May 1986 release of Run-DMC's Raising Hell, which sold more than three million copies, these included the Beastie Boys' Licensed to Ill (1986), Boogie Down Productions' Criminal Minded (1987), Public Enemy's Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987), and Eric B. & Rakim's Paid in Full (1987). According to The Boombox writer Todd "Stereo" Williams, this initiated hip hop's "golden age" as well as the genre's own "album era" from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, during which "hip-hop albums would be the measuring stick by which most of the genre's greats would be judged".[59] In response to rapidly developing trends in these latter decades of the album era, genres and formats were often renamed or regrouped, such as the categorization of earlier "pop/rock" music into the "classic rock" format.[57]

Transition to cassettes and CDs (1984–1999)

During the 1980s, the album format consolidated its domination of the recorded music market, first with the emergence of the cassette.[42] According to PC Mag columnist John C. Dvorak, "the album era had resulted in too many albums with only one good song on each of them, so cassettes let users do their own mixes", a trend expedited by the introduction of the Sony Walkman in 1979.[60] The introduction of the CD, along with the portable Discman player in 1984,[60] began the displacement of LPs in the 1980s as the standard album format for the music industry.[37] According to Hogan, "the spread of cassettes and CDs in the '80s broke up the album with home taping and easier song skipping".[49] In 1987, the music industry experienced its most profitable year yet due to the CD's increased popularity, highlighted by marketing successes such as Jackson, U2, Bruce Springsteen, Prince, Paul Simon, Whitney Houston, Sting, Bon Jovi, and Def Leppard, the latter two of whom represented a pop metal boom in the industry.[61] While net unit sales had actually declined,[61] Christgau reported in September 1987 that CDs were outpricing LP records and cassettes were outselling them,[62] although the cassette would also eventually be displaced by the CD.[60] In 1988, responding to the decade's developments, sociomusicologist Simon Frith predicted an imminent end to "the record era" and perhaps "pop music as we know it".[49]

In the transition to CDs, well-regarded albums of the past were reissued on the format by their original record labels, or the label to whom the album's ownership had been transferred in the event of the original's closure, for instance.[37] In 1987, the reissue of the Beatles' complete studio catalog was especially popular among consumers from the baby boomer generation, who were also the target audience of two classic-rock films – the Chuck Berry tribute Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll and the Ritchie Valens biopic La Bamba (with its accompanying soundtrack) – and Elvis Presley compilations commemorating the 10th anniversary of his death.[61] However, many older works were overlooked for digital rerelease "because of legal and contractual problems, as well as simple oversight", Strauss explains.[37] Instead, such records were often rediscovered and collected through the crate digging practices of North American hip hop producers seeking rare sounds to sample for their own recordings. In her account of the 1980s hip hop crate-diggers, media and culture theorist Elodie A. Roy writes, "As they trailed second-hand shops and car boot sales – depositories of unwanted capitalist surplus – diggers were bound to encounter realms of mainstream, mass-produced LP records now fallen out of grace and fashion." This development also contributed to the phenomenon of the "popular collector", which material culture scholar Paul Martin describes as those generally interested in "obtainable, affordable and appealing" items – such as music releases – and attributes to mass production.[63]

According to Pareles, after "the individual song returned as the pop unit" through the 1980s, record companies at the end of the decade began to abstain from releasing hit singles as a means of pressuring consumers to purchase the album on which the single featured.[43] By the end of the 1980s, seven-inch vinyl single sales were dropping and almost entirely displaced by cassette singles, neither of which ultimately sold as well as albums.[42] Album production proliferated in the 1990s, with Christgau approximating 35,000 albums worldwide were released each year during the decade.[64] In 1991, Nirvana's album Nevermind was released to critical acclaim and sold more than 30 million copies worldwide, leading to an alternative rock boom in the music industry.[49] A simultaneous country music boom led by Garth Brooks and Shania Twain[65] culminated with more than 75 million country albums sold in each of 1994 and 1995,[66] by which time the rap market was also increasing rapidly, particularly through the success of controversial gangsta rap acts such as Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg.[67] Meanwhile, single-song delivery of music to the consumer was almost nonexistent, at least in the US,[68] and in 1998, Billboard ended the requirement of a physical single for inclusion on its Hot 100 singles chart after several of the year's major hits were not released as singles to consumers.[69] In 1999, the music industry as a whole reached a commercial peak with $15 billion in record-sale revenue, mostly from CDs.[70]

Nirvana's Nevermind is cited by Eddy as roughly the end of the "high album era",[31] although Strauss wrote in 1995 that the "album-rock era" was still in effect.[37] As another "ending point", Hogan says critics have often named Radiohead's electronic-influenced 1997 album OK Computer, which progressed the boundaries of rock music while achieving a dual level of mainstream and critical success unmatched by any "guitar-based full-length" work in subsequent decades.[49] Kot, meanwhile, observed a decline in integrity among the industry and artists. He suggested that consumers had been exploited through the 1990s by increasing prices of CD albums, which were less expensive to produce than vinyl records, and had longer run times with considerably lower-quality music. While acknowledging some recording acts still attempted to abide by ideals from earlier in the album era, he said most had renounced their responsibilities as artists and storytellers and embraced indulgent recording practices in order to profit from the CD boom.[34]

2000s: Decline in the digital age, shift to pop and urban

At the turn of the 2000s, Kot published a faux obituary for the 33⅓ rpm LP form in the Chicago Tribune. In it, he argued that the LP had "been made obsolete by MP3 downloads, movie soundtracks and CD shufflers – not to mention video games, cable television, the Internet and the worldwide explosion of media that prey upon the attention spans of what used to be known as album buyers."[34] In 1999, the Internet peer-to-peer file sharing service Napster allowed Internet users to easily download single songs in MP3 format, which had been ripped from the digital files located on CDs.[71] Amidst Napster's rise in 2000, David Bowie predicted in an interview that the album era would end with the music industry's unavoidable embrace of digital music files.[72][nb 2] By early 2001, Napster use peaked with 26.4 million users worldwide.[73] Although Napster was shut down later that year for copyright violations, several other music download services took its place.[74]

In 2001, Apple Inc.'s iTunes service was introduced, and the iPod (a consumer-friendly MP3 player) was released later that year, soon to be joined by similar legal alternatives. This, along with a continued rise in illicit file sharing, led to a steep decline in the sales of recorded music on physical formats[68] over the next three years.[75] Sales briefly recovered by the end of 2004 when the industry registered approximately 667 million albums sold, led with 8 million from Confessions by Usher,[75] whose success exemplified urban music's commercial dominance of pop in the decade.[76] Eminem and 50 Cent were among the major-label successes of the rap boom that had continued from the previous decade.[67] Confessions and Eminem's The Eminem Show (2002) would both be certified Diamond by the Recording Industry Association of America, reaching 10 million copies sold each by the end of the decade.[76]

According to Hogan, the most innovative records were also being produced in the urban genres of R&B, hip hop, and pop, including albums by Kanye West and D'Angelo as well as the productions of Timbaland and the Neptunes. For critics, these works became another form of the full-length art pop records that had defined the album era with a rock guitar-based tradition, which was complicated further by the canonical acclaim afforded to Radiohead's electronic post-rock album Kid A (2000). Failing to match the landmark sales of OK Computer, the most acclaimed rock albums of the early 2000s often revisited older sounds, as with the Strokes' Is This It (2001), the White Stripes' White Blood Cells (2001), and Interpol's Turn on the Bright Lights (2002), or simply lacked Radiohead's extensive production and marketing budget, as in the case of Arcade Fire's Funeral (2004). These developments led to rock's commercial and cultural prestige diminishing and the critical paradigm shifting from rockism to poptimism in subsequent years.[49]

Meanwhile, the music industry's ability to sell albums still faced threats from piracy and competing media, such as DVDs, video games, and single-song downloading. According to Nielsen SoundScan's data for 2004, digital tracks had sold more than 140 million copies at around 99 cents each from online vendors like iTunes, indicating that consumers preferred to download individual songs over the higher-priced album in its entirety.[75] In 2006, CD sales were outnumbered for the first time by single downloads, with digital music consumers buying singles over albums by a margin of 19 to 1.[68] By 2009, album sales had more than halved since 1999, declining from a $14.6 to $6.3 billion industry.[78] Also by this time, dance-pop had succeeded urban music as the dominant genre on top 40 radio,[76] with pop artists like Rihanna emerging during this period basing their careers on digital singles instead of album sales.[79] Veteran rock acts like U2 prospered through the fall of album sales better than younger acts because of a loyal following that still held an attachment to the format. "Children of the album era as they were, U2 would never stop regarding the album as the core statement of their creativity" despite progressively lower sales, says Mat Snow, noting that live shows consequently became their greatest source of revenue.[70]

With the rise of digital media in the 2000s, the "popular collector" of physical albums had transitioned to the "digital" and "electronic" collector. Of such collectors, Roy says it can be argued they are "not equipped with sufficient archiving knowledge or tools to preserve his/her collection in the long run", citing the vulnerable shelf life of digital files.[63] Concurrently, the demise of physical music stores allowed for websites to emerge as domains for album collecting, including the music review database AllMusic, the streaming service Spotify, and Discogs, which began as a music database before developing into an online marketplace for physical music releases.[80]

The phrase "death of the album" was used in the media during the decline, usually attributing it to Internet sharing and downloading,[81][82] and the changing expectations of music listeners.[83] Capitol-EMI's COO Jeff Kempler said in 2007 that fewer artists will pursue album-oriented campaigns, while media researcher Aram Sinnreich bluntly predicted the album's death with consumers listening to playlists on their MP3 players instead.[68] In an interview several years later, Lee Phillips of the Californian entertainment law firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips believed the album era had ended and blamed record companies for failing to recognize the inevitability of streaming as the favored means of music distribution and for not working with Napster on a solution.[84]

2010s–present: post-album era and the streaming age

Music industry insiders[85] and writers in the 2010s, such as Jon Caramanica[86] and Kevin Whitehead,[87] have described this period in the album's history as the "post-album era". Over the course of the decade, record labels generally invested in streaming platforms such as Spotify and Pandora Radio, with strategies focused on curated playlists and individual tracks rather than albums.[2] Spotify in particular became a dominant and redefining platform for music consumption during the 2010s. Reporting later in the decade for Deseret News, Court Mann said that "services like Spotify and Apple Music have moved our [music] libraries off personal hard drives, iPods and CDs, and into the cloud. Our music is decreasingly self-contained and private."[88] In 2011, net album sales in the US rose for the first time since 2004 – with some writers attributing it to Adele's 2011 sleeper hit 21 (at 5.8 million units and more than three million CDs sold by January 2012)[89] – but continued to fall again the next year.[76] With consumers abandoning albums, more performers focused on releasing singles, a trend which critics felt undermined their artistic potential and produced many one-hit wonders.[90] However critics, who had primarily written reviews of albums during the format's era of dominance, had also begun reviewing single songs.[31]

While the album format was "dead" commercially, high-profile artists such as U2, the 1975, Taylor Swift, and Katy Perry still presented their work within a self-defined "album era", says Peter Robinson of The Guardian. Such artists presented their project's aesthetic lifetime in the style of themed album campaigns by past acts like Bowie, Madonna, and Pet Shop Boys.[91] Albums were marketed in extravagant, performance art-like product launches that reached "a nadir" in 2013, according to Vulture writer Lindsay Zoladz, who cites the failed attempts of acts such as Kanye West, Arcade Fire, and Lady Gaga at using visual art and public settings in the strategy: "Gaga's comically excessive ARTPOP campaign featured a Jeff Koons sculpture and a press conference in which she unveiled 'VOLANTIS, the world's first flying dress'; Daft Punk recorded endless VH1 Classic Albums–esque promotional spots that memorialized Random Access Memories before anybody had even heard it ... and then who could forget [Perry] driving through the streets of L.A. in a gilded 18-wheeler that screamed KATY PERRY PRISM 10-22-13 and looked, uncannily, like a ten-ton brick of Cracker Barrel cheese?"[92] Despite this, Swift remained the music industry's leading adherent and meticulous planner of album-era campaigns through the decade, creating a distinctive art of the strategy, in Curto's opinion.[58]

By the mid 2010s, popular recording artists had embraced the surprise album as a release strategy, issuing their albums with little or no prior announcement and promotion, in part as a way of combatting Internet leaks. This strategy was predated by Radiohead and Bowie but popularized by Beyoncé with her self-titled album in 2013, leading to what Zoladz in 2015 called the "current surprise-album era".[92] The following year, the singer repeated the strategy with her Lemonade album and again proved "the Zeitgeist could be captured and held in just one night", as Curto explains.[58] However, Zoladz went on to report a "collective fatigue" among professional critics and casual listeners from staying connected with surprise releases and the social-media news cycle surrounding them. She also noted Drake's ability to sustain his popular appeal over time more with single-track releases and thus mastering the digital age's "desire for both instant gratification and long-term anticipation".[92] The latter half of the 2010s trended toward similarly minimal marketing for hip hop album releases, with announcements in the form of social media posts unveiling only the cover art, track listing, or release date a few weeks prior at the most.[58]

Other critics still believed in the album as a viable concept in the 21st century. In 2003, Wired magazine had assigned Christgau to write an article discussing if the album was "a dying art form", to which he concluded: "For as long as artists tour, they'll peddle song collections with the rest of the merch, and those collections will be conceived as artfully as the artists possibly can." In 2019, as CD and digital download sales plummeted and theories still persisted about the "death" of the physical album format, Christgau found his original premise even more valid. "Because the computer giveth as the computer taketh away", he wrote in an essay accompanying the Pazz & Jop music poll that year, explaining that the current affordability of adequate recording equipment makes album production accessible to musicians of various levels of competence. Regarding professional acts, he said, "Writing songs is in their DNA, and if said songs are any good at all, recording them for posterity soon becomes irresistible."[93]

Even in the so-called post-album era of the 2010s, when listeners didn't have to purchase an album to hear it, the industry still hadn't moved on from albums, in large part because those extraneous elements of the rollout – the merch, the tour, the attention – still make record labels and other middlemen money.

In a year-ending essay on the album in 2019, Ann Powers wrote for Slate that the year found the format in a state of "metamorphosis" rather than dead. In her observation, many recording artists had revitalized the concept album around autobiographical narratives and personal themes, such as intimacy, intersectionality, African-American life, boundaries among women, and grief associated with death. She cited such albums as Brittany Howard's Jaime, Raphael Saadiq's Jimmy Lee, Rapsody's Eve, Jenny Lewis' On the Line, and Nick Cave's Ghosteen.[94] Writing contemporaneously, arts and culture journalist Michelle Zipkin believed albums are still "an integral, relevant, and celebrated component of musical creation and artistry". She cited the review aggregator Metacritic's tabulation of the most acclaimed albums from the 2010s, which showcased musicianship from a diverse range of artists and often serious themes, such as grief, race relations, and identity politics, while adding that, "Albums today offer a fresh way of approaching a changing industry".[2]

By 2019, Swift remained the only artist "who still sells CDs" and had yet to embrace streaming services because they had not compensated recording artists fairly, according to Quartz. Elaborating on this point, Los Angeles Times critic Mikael Wood said, "Yet as she kept her music off Spotify – conditioning her loyal audience to think of buying her songs and albums as an act of devotion – younger artists like [Ariana] Grande emerged to establish themselves as streaming favorites." However, Swift used all major streaming services to release her 2019 album Lover, which Quartz said "might be the last CD we buy" and was "perhaps a final death note for the CD".[95]

International trends

By the mid 2010s, physical CD and vinyl sales made up 39% of global music sales. Out of total music sales in the US (the world's largest music market in terms of revenue), less than 25% were physical copies, while France and the UK both registered around 30–40% in this same statistic. However, that figure was approximately 60% for Germany and 75% for Japan, which had the world's second largest market with more than ¥254 billion (or $2.44 billion) sold per year in music recordings, most of them in the form of CDs. Both countries led the world in physical music sales partly because of their cultures' mutual affinity for "physical objects", according to Quartz journalist Mun Keat Looi.[96]

The Japanese industry had especially favored the CD format, due in part to its ease of manufacturing, distributing, and pricing control. In 2016, Japan had 6,000 physical music stores, leading the US (approximately 1,900) and Germany (700) for most in the world. Despite broadband Internet being available in Japan since 2000, consumers had resisted the change to downloaded and streamed consumption, which made up 8% of the country's total music revenue, compared to 68% in the US market. While singles in Western countries had been antiquated for more than a decade, Japan's market for them endured largely because of the immense popularity of idol entertainers, boy bands, and girl groups. Capitalizing on the fandom surrounding these performers, record companies and marketing agencies exploited the merchandising aspect of CDs with promotional gimmicks, such as releasing various editions of a single album, including them with tickets to artist events, and counting CD-single purchases as fan votes toward popularity contests for artists. The focus went away from the music and toward the fan experience of connectivity with a favorite idol, according to The Japan Times correspondent Ronald Taylor.[96]

Japan's unusual consumer behavior in the recorded music market was an example of the Galápagos syndrome, a business concept framed after Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory. According to Looi, it explains how the country's innovative but isolationist character had resulted in "a love for a technology that the rest of the world has all but forgotten". On the enduring commercial popularity of CDs there, global music analyst Mark Mulligan explained that Japan's purchasing power and consumer demand had been concentrated among its rapidly aging population who were more likely to follow veteran idols like the boy band Arashi and the singer-songwriter Masaharu Fukuyama, while less concentrated among young people attuned to digital and streaming services. However, the mid 2010s also saw an increase in digital music and subscription sales, indicating a trend away from physical purchases in the country.[96]

In 2019, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) reported among the world's top-10 recorded music markets to be Japan, China, South Korea, and Australia, while noting an emergence of markets outside the West in general, including those in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The report also observed a shift away from the global dominance of popular English-language acts and toward regional successes with cross-cultural appeal, such as BTS and J Balvin, due in part to a more open-minded consumer culture and social connectivity between artists and listeners. While top recording artists from the West continued to rely on traditional roles from major labels, others utilized digital service providers such as Spotify and Apple Music to either self-release their recordings or release them in partnership with an independent distributor.[98]

Pandemic period

In 2020, album launches were hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic and its related social distancing measures.[58] Between March 6 and 12, physical album sales fell 6% due in part to the pandemic. Later that month, Amazon temporarily suspended incoming shipments of music CDs and vinyl records from US suppliers in an effort to prioritize items deemed more essential.[2] The pandemic's closure of physical retailers and distribution systems impacted veteran recording acts especially, as their fans tended to be older and more likely to still purchase CDs and vinyl records. Consequently, many such acts who still adhered to a traditional rollout model, such as Willie Nelson and Alicia Keys, delayed their album releases.[99] Reporting on the development in March, Rolling Stone journalist Elias Leight explained:

That's because tens of thousands of new tracks appear on streaming services daily. To rise above the deluge, videos need to be shot months in advance, TV appearances need to be wrangled, streaming service curators courted, press opportunities locked down, tour dates and radio station visits and record store appearances lined up. Without these components, artists risk releasing music to an uninterested, unaware, or simply overwhelmed public. And right now, almost all these profile-raising options are out of reach.[100]

Some major pop stars reimagined their release strategies during the pandemic. Taylor Swift surprise-released her albums Folklore and Evermore in July and December 2020, respectively, abandoning a proper rollout campaign for the first time in her career, and setting several sales and streaming records. Ariana Grande, more inspired by rap release strategies, released her album Positions (2020) with similarly minimal announcement and promotion. The success of both artists during the pandemic came while more established pop stars had planned traditional album launches, including Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, and Dua Lipa.[58] Keys also surprise-released her album Alicia after an indefinite delay due to the pandemic.[101] Concurrently, rap albums benefited further from the period's more on-demand consumer and streaming culture, with rappers such as Lil Uzi Vert, Bad Bunny, and DaBaby topping album charts.[58]

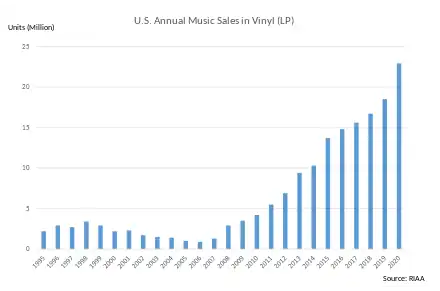

2020 proved the most successful year for vinyl albums in MRC Data history (since 1991), with 27.5 million sold in the US. In June 2021, Billboard reported that net physical album sales had risen for the first time in years due to the pandemic. Pop and hip hop/R&B artists gained more sales than ever in the US vinyl market, while rock records experienced a decline despite accounting for more than half of the market's total sales. Among the year's top vinyl sellers were Harry Styles, Billie Eilish, Kendrick Lamar, and Swift, whose Evermore led sales of both CDs and vinyl albums released in 2021.[102]

Reporting on music release trends during the pandemic, writers observed that they offered a greater connectivity for artists with their listeners during a paradigm-shifting period while empowering both groups at the expense of major labels.[58] However, Oliver Tryon of the music webzine CULTR argues that the music industry remains one of the most profitable markets worldwide and has capitalized on changing trends in the streaming age, including the increasing brevity of songs, diminishing genre distinctions among artists, and innovations in electronic music technology, such as the application of artificial intelligence in music. On developments in 2021, Tryon predicted that regional releases from around the world would rise in the global market and "generative music" would "rise as a result of contextual playlists", while albums in general would "continue to decline as the post-album era is becoming more prominent".[103]

In 2022, Michael Cragg wrote a piece for i-D magazine in which he questioned whether Swift was "our last remaining real popstar", noting her ability to combine traditional methods of marketing pop music, such as album-based metanarratives and massive concert tours, with contemporary tactics, such as abstaining from releasing songs ahead of the album. Pointing to the release of her Midnights (2022) album and the career-spanning Eras Tour, Cragg wrote that Swift had "harnessed [a] sense of pop communion" as "its very own high priestess" and created "a hysteria unseen since the industry's golden era".[104]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Blonde on Blonde (1966) and the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds (1966) are also named by Graff as possible starting points to the album era, constituting "a cohesive and conceptual body of work rather than just some hit singles ... with filler tracks."[20]

- ↑ Bowie went on to tell The New York Times in 2002, "I don't even know why I would want to be on a label in a few years, because I don't think it's going to work by labels and by distribution systems in the same way. The absolute transformation of everything that we ever thought about music will take place within 10 years, and nothing is going to be able to stop it."[72]

References

- ↑ Bus, Natalia (August 3, 2017). "An ode to the iPod: the enduring impact of the world's most successful music player". New Statesman. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Zipkin, Michele (April 8, 2020). "Best albums from the last decade, according to critics". Stacker. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Byun, Chong Hyun Christie (2016). "Introduction". The Economics of the Popular Music Industry: Modelling from Microeconomic Theory and Industrial Organization. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 9781137467058.

- 1 2 Degener, Andrea (September 18, 2014). "Visual Harmony : A Look At Classical Music Album Covers". Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ↑ Reitano, Bryce (August 24, 2019). "How Much Music Can Fit on a Vinyl Record?". Peak Vinyl. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- 1 2 Tomasky, Michael (May 31, 2017). "How the Hippies Hijacked Vinyl". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- 1 2 Murphy, Colleen "Cosmo" (n.d.). "The Art of the Album Part One". Classic Album Sundays. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ↑ Maslon, Laurence. ""South Pacific" (Original Cast Recording) (1949)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- ↑ "LP's 54% of Pop Sales - Lieberson". Variety. March 12, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved October 1, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ↑ Powers, Ann (July 24, 2017). "A New Canon: In Pop Music, Women Belong at the Center of the Story". NPR. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (2003). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955-2002. Record Research. p. xxiii. ISBN 9780898201550.

- 1 2 3 Danesi, Marcel (2017). Concise Dictionary of Popular Culture. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 15, 72. ISBN 978-1-4422-5311-7.

- 1 2 3 Shuker, Roy (2012). Popular Music Culture: The Key Concepts. Routledge. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-136-57771-0.

- ↑ Cullen, Jim (2001). Restless in the Promised Land. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-58051-093-6.

- ↑ Murray, Noel (July 5, 2006). "Inventory: 12 Delightfully Odd Concept Albums". The A.V. Club. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ↑ Friedwald, Will (2017). "Dinah Washington: Dinah Washington Sings Fats Waller (1957)". The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums. Pantheon Books. ISBN 9780307379078.

- ↑ Browne, David (July 28, 2021). "Woody Guthrie Returns, Thanks to Modern Indie and Americana Acts". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- 1 2 Smith, Chris (2009). 101 Albums that Changed Popular Music. Oxford University Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0-19-537371-4.

- ↑ Starr, Larry (2007) [2006]. American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MP3 (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN 9780195300536.

- 1 2 Graff, Gary (September 22, 2016). "Brian Wilson Celebrates 50th Anniversary of Landmark 'Pet Sounds'". Daily Tribune.

- ↑ Martin, Bill (1998). Listening to the Future: The Time of Progressive Rock, 1968–1978. Chicago, IL: Open Court. p. 41. ISBN 0-8126-9368-X.

- ↑ Howard, David N. (2004). Sonic Alchemy: Visionary Music Producers and Their Maverick Recordings. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-634-05560-7.

- ↑ Staff writer (January 15, 1966). "Teen Market Is Album Market". Billboard. p. 36.

- ↑ Perone, James E. (2004). Music of the Counterculture Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-313326899.

- 1 2 Harrington, Joe S. (2002). Sonic Cool: The Life & Death of Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. pp. 112, 192. ISBN 978-0-634-02861-8.

- 1 2 Simonelli, David (2013). Working Class Heroes: Rock Music and British Society in the 1960s and 1970s. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-7391-7051-9.

- ↑ Snow, Mat (2015). The Who: Fifty Years of My Generation. Race Point Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-1627887823.

- ↑ Pareles, Jon (January 5, 1997). "All That Music, and Nothing to Listen To". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- 1 2 Chris Kokenes. "'A Day in the Life' Lyrics to be Auctioned." CNN.com. April 30, 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Plagenhoef, Scott (September 9, 2009). "The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band". Pitchfork. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- 1 2 3 Eddy, Chuck (2011). Rock and Roll Always Forgets: A Quarter Century of Music Criticism. Duke University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-82235010-1.

- ↑ Hamilton, Jack (May 24, 2017). "Sgt. Pepper's Timing Was As Good As Its Music". Slate. Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ↑ Philo, Simon (2015). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8108-8626-1.

- 1 2 3 Kot, Greg (June 20, 1999). "R.I.P. 33 R.P.M." Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- 1 2 Italie, Hillel (May 22, 2017). "Not just 'Sgt. Pepper': Many 1967 musical firsts echo today". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021 – via pjstar.com.

- ↑ Dave Marsh. Review of "Purple Haze" in The Heart of Rock & Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made. Dave Marsh. Da Capo Press, 1999. p. 178. ISBN 9780306809019

- 1 2 3 4 5 Strauss, Neil (June 1, 1995). "The Pop Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ↑ Wynn, Ron (2001). "Isaac Hayes". In Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (eds.). All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music. Backbeat Books/All Media Guide. p. 183. ISBN 9780879306274.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (May 2008). "Otis Redding: Otis Blue". Blender. Retrieved June 13, 2021 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (March 17, 1998). "Queen of Pop". The Village Voice. Retrieved February 27, 2021 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ↑ Coelho, Victor (2019). "Exile, America, and the Theater of the Rolling Stones, 1968–1972". In Covach, John; Coelho, Victor (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9781107030268.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Hagan, Steve (director) (February 8, 2013). When Albums Ruled the World (Documentary film). UK: BBC Four. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pareles, Jon (July 7, 1991). "Pop View: As MTV Turns 10, Pop Goes the World". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Powers, Ann (January 26, 2009). "CD: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ↑ Martin, Bill (1998). Listening to the Future: The Time of Progressive Rock. Open Court. p. 41. ISBN 0-8126-9368-X.

- ↑ Beck, John H. (2013). "Progressive rock". Encyclopedia of Percussion. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317747673.

- ↑ Riedy, Jack (May 24, 2018). "The 10 Best Brian Eno Albums to Own on Vinyl". Vinyl Me, Please. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ↑ McCann, Ian (September 8, 2019). "70s Motown Albums You Need To Know: Overlooked Soul Classics Rediscovered". uDiscover. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hogan, Marc (March 20, 2017). "Exit Music: How Radiohead's OK Computer Destroyed the Art-Pop Album in Order to Save It". Pitchfork. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ↑ Olsen, Eric (March 30, 2004). "The 10 best rock bands ever". Today.com. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ↑ Perone, James E. (2016). Smash Hits: The 100 Songs That Defined America: The 100 Songs That Defined America. ABC-CLIO. p. 223. ISBN 978-1440834691.

- 1 2 3 4 Campion, James (2015). "5) School's Out". Shout It Out Loud: The Story of Kiss's Destroyer and the Making of an American Icon. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1617136450.

- ↑ Zanes, Warren (September 16, 2004). "Damn the Torpedoes". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (1981). "The Criteria". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251. Retrieved April 6, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ↑ The 1976 World Book Year Book. World Book Educational Products of Canada. 1976. p. 440. ISBN 9780716604761.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (March 19, 1985). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- 1 2 Restall, Matthew (2020). Elton John's Blue Moves. Bloomsbury Publishing. Chapters 3, 6. ISBN 9781501355431.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Curto, Justin (December 22, 2020). "Did 2020 Kill the Long, Fancy Pop-Album Rollout for Good?". Vulture. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ↑ Williams, Todd "Stereo" (May 16, 2016). "How Run-D.M.C.'s 'Raising Hell' Launched Hip-Hop's Golden Age". The Boombox. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Dvorak, John C. (May 21, 2002). "Muddy Thinking and the Music Biz". PC Mag. p. 57.

- 1 2 3 McDannald, Alexander Hopkins, ed. (1988). "Music". The Americana Annual: An Encyclopedia of Current Events. Americana Corporation. pp. 381–382.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (September 29, 1987). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- 1 2 Roy, Elodie A. (2016). Media, Materiality and Memory: Grounding the Groove. Routledge. pp. 118, 119, 167, 177. ISBN 978-1317098744.

- ↑ Klein, Joshua (March 29, 2002). "Robert Christgau: Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums Of The '90s". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ↑ Jensen, Joli (2002). "Taking Country Music Seriously". In Jones, Steve; Baker, Susan S. (eds.). Pop Music and the Press. Temple University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9781566399661.

- ↑ Adams, Mark (January 15, 1996). "Turning Dow the Music". Mediaweek. p. 3.

- 1 2 Sorapure, Madeleine; Petracca, Michael, eds. (2007). Common Culture: Reading and Writing about American Popular Culture. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 298. ISBN 9780132202671.

- 1 2 3 4 Jeff Leeds. "The Album, a Commodity in Disfavor." The New York Times. March 26, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ "How The Hot 100 Became America's Hit Barometer". NPR. August 1, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- 1 2 Snow, Mat (2014). U2: Revolution. Race Point Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 9781937994990.

- ↑ Brown, Andrew R. (2007). Computers in Music Education: Amplifying Musicality. Routledge. p. 194. ISBN 978-0415978507.

- 1 2 Popkin, Helen A. S. (January 11, 2016). "Tech Visionary David Bowie Foresaw Individual Branding; Limitless Music". Forbes. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ↑ Jupiter Media Metrix (July 20, 2001). "Global Napster Usage Plummets, But New File-Sharing Alternatives Gaining Ground". comScore.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ohmae, Kenichi; Ōmae, Ken'ichi (2005). The Next Global Stage. Wharton School Pub. p. 231. ISBN 9780131479449.

- 1 2 3 Anon. (January 5, 2005). "Album Sales: Expected to Show 1.6% Rise". The New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Molanphy, Chris (July 16, 2012). "100 & Single: The R&B/Hip-Hop Factor In The Music Business's Endless Slump". The Village Voice. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ↑ James, Andy (February 8, 2018). "8 Greatest Hip-Hop Producers of All Time". DJBooth. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Why Album Sales Are Down". Speeli. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ↑ SPIN Staff (October 5, 2015). "How Rihanna's 'Umbrella' Changed Her Career Forever, By John Seabrook". Spin. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ↑ Buck, David (August 8, 2019). "Vinyl Collecting in 2019". tedium. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ↑

- Baneriee, Scott (November 6, 2004), "New Ideas, New Outlets", Billboard, Prometheus Global Media, p. 48

- ↑ Kiss, Jemima (August 29, 2008), "The death of the album", Guardian.co.uk, Guardian Media Group, retrieved December 16, 2012

- ↑ Paxson, Peyton (2010), Mass Communications and Media Studies: An Introduction, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 84, ISBN 9781441108951

- ↑ Trakin, Roy (April 15, 2014). "Music Attorney Lee Phillips: 'Labels Made a Mistake by Not Doing a Deal with Napster'". The Hollywood Reporter. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ↑ Mazor, Barry (September 9, 2010). "A New Country Masterpiece". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ Caramanica, Jon (August 29, 2019). "What's the Point of Album Covers in the Post-Album Era?". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ Whitehead, Kevin (2010). Why Jazz?: A Concise Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780199753109.

- ↑ Mann, Court (December 26, 2019). "How the 2010s changed our music listening habits — and music itself". Deseret News. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (January 13, 2012). "Dad-Rock Makes a Stand". The Barnes & Noble Review. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ↑ Tejas Morey. "How iTunes Changed The Music Industry Forever." MensXP (Times of India). Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Robinson, Peter (September 1, 2017). "Achtung, maybe? The album is dead: all hail the rise of the 'era'". The Guardian. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Zoladz, Lindsay (April 8, 2015). "Everybody 'Pulling a Beyoncé' Has Given Me Surprise-Album Fatigue". Vulture. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (February 7, 2019). "Pazz & Jop: The Dean's List". The Village Voice. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ↑ Powers, Ann (December 17, 2019). "The album is evolving". Slate. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ↑ Singh-Kurtz, Sangeeta; Dan, Kopf (August 23, 2019). "Taylor Swift is the only artist who still sells CDs". Quartz. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Looi, Mun Keat (August 19, 2016). "Why Japan has more old-fashioned music stores than anywhere else in the world". Quartz. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ↑ "ARASHI Awarded Global Album of 2019 for Their 20th Anniversary Compilation 5x20 All the BEST!! 1999–2019". IFPI. March 19, 2020.

- ↑ Paine, Andre (April 3, 2019). "'We are seeing growth in local repertoire everywhere': Six key insights from the IFPI Global Music Report". Music Week. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ↑ Christensen, Thor (March 23, 2020). "Willie Nelson Pushes New Album Release Back to July Because of Pandemic". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ Leight, Elias (March 30, 2020). "They Were Going to Be Spring's Biggest Albums – Until COVID-19 Hit". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ Smith, Nick (September 18, 2020). "Alicia Keys – Alicia". musicOMH. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ DiGiacomo, Frank (June 8, 2021). "Hip-Hop, R&B And Pop Challenge Rock's Vinyl Dominance In 2021". Billboard. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ↑ Tryon, Oliver (February 17, 2021). "Top Electronic Music Trends To Come In 2021". CULTR. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ Cragg, Michael (December 11, 2022). "Is Taylor Swift our last remaining real popstar?". i-D. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

Further reading

- Christgau, Robert (August 31, 2022). "The Big Lookback: The Singles vs. Albums Debate – Remarks from a 2013 New Music Seminar panel". And It Don't Stop. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- Cross, Alan (February 2, 2020). "Are you still listening to albums the old-fashioned way? Chances are you're not: Alan Cross". Global News. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Davies, Sam (September 2021). "From Kanye to Drake, Album Hype Has Eclipsed the Music". Highsnobiety. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- Ducker, Eric (August 19, 2015). "A Rational Conversation: Does Anybody Even Have Time for an 80-Minute Album?". NPR. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Ivakhiv, Adrian J. (May 8, 2017). "Greatest Albums of the LP Era". immanence. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Lefsetz, Bob (September 12, 2013). "Classic Rock's Era of the Album Gives Way to Today's Track Stars". Variety. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Moran, Robert (September 6, 2021). "What makes a number one album these days – and does it even matter?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- Richardson, Mark (October 6, 2020). "Rolling Stone's Canon Fodder". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- Smith, Troy L. (September 21, 2017). "15 Greatest Years in Music History". Cleveland.com. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Sullivan, Caroline (October 3, 2005). "Death of the album". The Guardian. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Wachs, Jeffrey Philip (December 2012). "The Long-Playing Blues: Did the Recording Industry's Shift from Singles to Albums Violate Antitrust Law?". UC Irvine Law Review. 2 (3). Retrieved June 26, 2021.

External links

- Albumism – online magazine dedicated to album-related content

_002.JPG.webp)