Alfred Alexander Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office January 15, 1921 – January 16, 1923 | |

| Preceded by | Albert H. Roberts |

| Succeeded by | Austin Peay |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1889 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | Roderick R. Butler |

| Succeeded by | William C. Anderson |

| Member of the Tennessee House of Representatives | |

| In office 1874–1876 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 6, 1848 Carter County, Tennessee |

| Died | November 25, 1931 (aged 83) Johnson City, Tennessee |

| Resting place | Monte Vista Memorial Park, Johnson City |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Jennie Anderson (m. 1881)[1] |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Profession | Attorney |

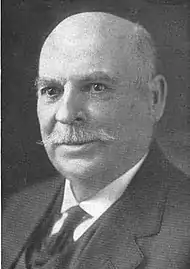

Alfred Alexander Taylor (August 6, 1848 – November 25, 1931) was an American politician and lecturer from eastern Tennessee. He served as the 34th governor of Tennessee from 1921 to 1923, one of three Republicans to hold the position from the end of Reconstruction to the latter half of the 20th century. He also served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, from 1889 to 1895.[1]

In 1886, Taylor ran for governor against his younger brother, Democrat Robert Love Taylor (1850–1912), in a memorable campaign known as the "War of the Roses." Canvassing the state together, the brothers often engaged in light-hearted banter and played fiddles, in contrast to previous gubernatorial campaigns, which involved fierce debates.[2] Taylor ran for governor again in 1910, but lost his party's nomination to Ben W. Hooper. He was victorious in 1920 due in large part to divisions within the Democratic Party over taxes and women's suffrage.[3]

Early life

Taylor was born in the Happy Valley community of Carter County, Tennessee, the second son of Nathaniel Green Taylor, a congressman, Methodist minister, and poet, and Emaline Haynes Taylor, an accomplished pianist.[2]: 23 Nathaniel Taylor was a Whig (many of whom later became Republicans), while his wife's family, among them her brother, Landon Carter Haynes, were Democrats. Alfred followed his father into the Republican Party, while his brother, Robert, followed their mother's family into the Democratic Party.[1]

Taylor attended Duffield Academy in Elizabethton, Tennessee and Buffalo Institute (modern Milligan College) in Carter County, Tennessee. Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Nathaniel Taylor supported the Union, and the Taylors were forced to move to the North.[2]: 19 During this period, Alfred attended Pennington Seminary in Pennington, New Jersey.[1]

In 1867, Taylor accompanied his father, then Commissioner of Indian Affairs under President Andrew Johnson, to join the Indian Peace Commission in Kansas in an effort to end the Plains Wars. The commission negotiated the Medicine Lodge Treaty with the southern Plains Indians, bringing about their removal to reservations in Indian Territory. In 1924, Taylor wrote an account of this trip and published it in the Chronicles of Oklahoma.[4]

After his study of law, Taylor was admitted to the bar in 1870 and commenced practice in Jonesborough, Tennessee.[5]

Early political career

Taylor was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1874, and served one term. Among his initiatives was the creation of Unicoi County in 1875. He would later refer to the county as, "my baby."[2]: 35 Taylor served as an elector for Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, and would serve as an elector in the three subsequent presidential campaigns.[6]

In 1878, Taylor sought his party's nomination for the 1st district congressional seat held by Augustus Pettibone. Although Taylor had popular support, Pettibone managed to win the nomination at the party's convention, angering Taylor's supporters. Taylor's brother, Robert (a Democrat), ran against Pettibone in the general election, and with the support of both Democrats and his brother's disgruntled supporters, captured the seat. He was defeated for reelection by Pettibone after just one term, and no Democrat has been elected to the seat since.[7][2]: 40

In Tennessee's 1886 gubernatorial race, Republicans, hoping to exploit divisions within the Democratic Party, nominated Alfred Taylor as their candidate. Democrats nominated his brother, Robert, believing him the best person to unite the party and counter Alfred's popular appeal. The brothers canvassed the state together, drawing large crowds, and engaging in light-hearted political debate and playing fiddles while the crowd danced. At a stop in Madisonville, Robert stated that he and Alfred were both roses, though he was a white rose while Alfred was a red rose. When their respective supporters wore white and red roses, the contest became known as the "War of the Roses" (the name also hearkened to the 15th-century English conflict). On election day, Robert won by about 16,000 votes.[3]

The 1886 campaign boosted Alfred Taylor's popularity. In 1888, he successfully ran for the 1st district congressional seat, defeating Democrat David P. Wilcox by 7,000 votes.[8] He was reelected in 1890, edging Roderick R. Butler (who ran as an independent) by less than a thousand votes.[9] He was reelected to a third term in 1892. During his congressional tenure, Taylor supported the McKinley Tariff, a protectionist measure that raised tariffs on imports by 50%. He also supported the Lodge Bill, which would have provided protections for black voters in the South.[1]

After leaving Congress, Taylor joined his brother, Robert, on the lecture circuit. They cowrote and presented a popular lecture entitled "Yankee Doodle and Dixie."[1] The tour was a major financial success, netting the brothers tens of thousands of dollars.[2]: 64

In 1906, Taylor ran as an independent for the 1st district seat against state Republican Party boss, Walter P. Brownlow, but was defeated by a substantial margin. In 1910, Taylor sought the Republican nomination for governor, but was defeated by Ben W. Hooper. Hooper then proceeded to defeat Alfred's brother, Robert, in the general election.[3]

Governor

In 1920, the 71-year-old Taylor was nominated by Republicans for governor. His opponent was the Democratic incumbent, Albert H. Roberts, who had alienated a significant portion of his party by enacting unpopular tax reforms and helping ratify the 19th Amendment (which gave women the right to vote). On the campaign trail, Taylor travelled with a four-piece quartet (consisting of three of his sons and their friend), and told the story of "Old Limber," a foxhound who, in spite of his old age, could still outrun the pack.[2]: 81 As he also supported the 19th Amendment, he campaigned primarily against Roberts' tax reforms. On election day, he defeated Roberts 229,143 votes to 185,890.[3] It was the state's first gubernatorial election in which women could vote.[1]

Following his inauguration, Taylor focused on what he termed the "Big Four" issues: tax reform, rural school reform, highways, and the economy.[1] Although most of his agenda was blocked by the state legislature (which was controlled by Democrats), he created the position of tax commissioner, obtained funding for a state historical commission, and resolved several labor disputes.[3] He also helped convince the federal government to convert a nitrate plant built for World War I at Wilson Dam in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, into an electrical power plant for the benefit of the inhabitants of the Tennessee Valley.[3]

In 1922, the Democratic Party nominated former party leader Austin Peay to oppose Taylor for governor. Peay lacked the charisma of Taylor, and resorted to delivering basic stump speeches, in contrast to Taylor's entertaining rallies. Peay had the support of entrepreneur Clarence Saunders (the founder of Piggly Wiggly), and with the Democratic Party once again unified, he defeated Taylor on election day, 141,002 votes to 102,586.[3]

Later life

Following his defeat in the 1922 governor's race, Taylor returned to his farm near Johnson City, Tennessee. He died on November 25, 1931, and was buried in the city's Monte Vista Cemetery.

Family

Taylor's great-grandfather, General Nathaniel Taylor (1771–1816), served during the War of 1812.[2]: 17 Another great-grandfather, Landon Carter (1760–1800), was a Revolutionary War veteran for whom Carter County was named.[10] Taylor's uncle, Landon Carter Haynes, was a leading East Tennessee Democrat during the Civil War, and served in the Confederate Senate. Taylor was a cousin of Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who served as Governor of Georgia from 1915 to 1917.

Taylor married Jennie Anderson in 1881, and they had ten children together.[4] Their son, Robert Love Taylor (1899–1987), named for Alfred's brother, became a United States federal judge.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Robert L. Taylor, Jr., "Alfred Alexander Taylor," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: 6 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Paul Deresco Augsburg, Bob and Alf Taylor: Their Lives and Lectures (Morristown, Tenn.: Morristown Book Company, 1925).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Phillip Langsdon, Tennessee: A Political History (Franklin, Tenn.: Hillsboro Press, 2000), pp. 300–303.

- 1 2 A.A. Taylor, "MEDICINE LODGE PEACE COUNCIL" Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 2, No. 2, June 1924, accessed 21 January 2011

- ↑ Finding Aid for Governor Alfred A. Taylor Papers Archived 2013-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, Tennessee State Library and Archives, 1968. Retrieved: 6 December 2012.

- ↑ John Allison, Notable Men of Tennessee (Southern Historical Association, 1905), pp. 326–327.

- ↑ "History of Tennessee's 1st Congressional District". Our Campaigns. Our Campaigns.

- ↑ Our Campaigns – TN District 01, 1888. Retrieved: 6 December 2012.

- ↑ Our Campaigns – TN District 01, 1890. Retrieved: 6 December 2012.

- ↑ W. Calvin Dickinson, "Landon Carter," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Clinton J. Holloway, "A Place to call home: Remarks on the Williams-Taylor House, Milligan College, Tennessee on the occasion of the renovation and dedication as the Taylor-Phillips House" Archived 2008-09-08 at the Wayback Machine, Milligan College (October 25, 2002).

Further reading

- Taylor, Robert L., Jr. "Apprenticeship in the First District: Bob and Alf Taylor's Early Congressional Races." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 28 (Spring 1969): 24–41.

- Taylor, Robert L., Jr. "Tennessee's War of the Roses as Symbol and Myth," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 41 (1982): 337–59.

External links

- Alfred Alexander Taylor – entry at the National Governors Association

- Governor Alfred A. Taylor Papers, 1921 - 1923, Tennessee State Library and Archives.