Alice Ayres | |

|---|---|

Ayres and child | |

| Born | 12 September 1859 Isleworth, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 26 April 1885 (aged 25) Guy's Hospital, Southwark, London, England |

| Resting place | Isleworth Cemetery, England |

| Occupation | Household assistant/nursemaid |

| Known for | Rescuing three nieces from burning building at 194 Union Street, Southwark, before falling to her death |

Alice Ayres (12 September 1859 – 26 April 1885) was an English nursemaid honoured for her bravery in rescuing the children in her care from a house fire. Ayres was a household assistant and nursemaid to the family of her brother-in-law and sister, Henry and Mary Ann Chandler. The Chandlers owned an oil and paint shop in Union Street, Southwark, then just south of London, and Ayres lived with the family above the shop. In 1885 fire broke out in the shop, and Ayres rescued three of her nieces from the burning building, before falling from a window and suffering fatal injury.

Britain, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, experienced a period of great social change in which the rapidly growing news media paid increasing attention to the activities of the poorer classes. The manner of Ayres's death caused great public interest, with large numbers of people attending her funeral and contributing to the funding of a memorial. Shortly after her death, she underwent what has been described as a "secular canonisation", being widely depicted in popular culture and, although very little was known about her life, widely cited as a role model. Various social and political movements promoted Ayres as an example of the values held by their particular movement. The circumstances of her death were distorted to give the impression that she was an employee willing to die for the sake of her employer's family, rather than for children to whom she was closely related. In 1902 her name was added to the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice and in 1936 a street near the scene of the fire was renamed Ayres Street in her honour.

The case of Alice Ayres came to renewed public notice with the release of Patrick Marber's 1997 play Closer, and the 2004 film based on it. An important element of the plot revolves around a central character who fabricates her identity based on the description of Ayres on the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, with some of the film's scenes shot around the memorial.

Work with the Chandler family

Alice Ayres was born into a large family in 1859, the seventh of ten children of a labourer, John Ayres. In December 1877, her sister Mary Ann (older than Alice by eleven years) married an oil and paint dealer, Henry Chandler. Chandler owned a shop at 194 Union Street in Southwark, about 400 yards (370 m) south of the present-day Tate Modern.[1]

In 1881 Ayres worked as a household assistant to Edward Woakes, a doctor specialising in ear and throat disorders.[2] By 1885 she had become a household assistant and nursemaid to the Chandlers, living with the family.[2] After her death, Ayres was described by a local resident as "not one of your fast sort—gentle and quiet-spoke, and always busy about her work".[3] Another neighbour told the press that "no merry making, no excursion, no family festivity could tempt her from her self-imposed duties. The children must be bathed and put to bed, the clothes must be mended, the rooms must be 'tidied up', the cloth must be laid, the supper carefully prepared, before Alice would dream of setting forth on her own pleasures".[3][n 1]

Union Street fire

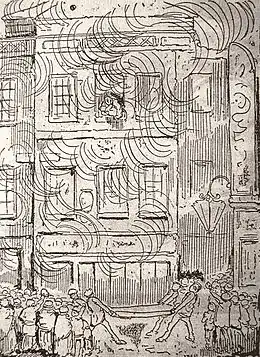

The Chandlers' shop at Union Street, as depicted in a contemporary newspaper illustration, occupied the corner premises of a building of three storeys. The family lived above the shop, with Henry and Mary Ann Chandler sleeping in one bedroom with their six-year-old son Henry, and Ayres sharing a room on the second floor with her nieces, five-year-old Edith, four-year-old Ellen and three-year-old Elizabeth.[1] On the night of 24 April 1885, fire broke out in the oil and paint shop, trapping the family upstairs.[1] Gunpowder and casks of oil were stored in the lower floors of the building, causing the flames to spread rapidly.[4] Although the shop was near the headquarters of the London Fire Brigade and the emergency services were quickly on scene, by the time the fire engine arrived intense flames were coming from the lower windows, making it impossible for the fire brigade to position ladders.[5] Meanwhile, Ayres, wearing only a nightdress, had tried to reach her sister but was unable to get to her through the smoke.[6] The crowd that had gathered outside the building were shouting to Ayres to jump.[5] Instead she returned to the room she shared with the three young girls and threw a mattress out of the window, carefully dropping Edith onto it.[1] Despite further calls from below to jump and save herself,[4] she left the window and returned carrying Ellen.[1] Ellen clung to Ayres and refused to be dropped, but Ayres threw her out of the building, and the child was caught by a member of the crowd.[6] Ayres went back into the smoke a third time and returned carrying badly injured Elizabeth, whom she dropped safely onto the mattress.[1]

After rescuing the three girls, Ayres tried to jump herself, but overcome by smoke inhalation, fell limply from the window, striking the projecting shop sign.[7] She missed the mattress and the crowd below and fell onto the pavement, suffering spinal injuries. Ayres was rushed to nearby Guy's Hospital[1] where, because of the public interest that her story excited, hourly bulletins were issued about her health and Queen Victoria sent a lady-in-waiting to enquire after her condition.[8]

The oil and paint stored in the shop caused the fire to burn out of control, and when the fire services were eventually able to enter the premises the rest of the family were found dead. The body of Henry Chandler was found on the staircase, still clutching a locked strongbox filled with the shop's takings,[5] while the badly burnt remains of Mary Ann Chandler were found lying next to a first floor window, the body of six-year-old Henry by her side.[6] Ayres's condition deteriorated and she died in Guy's Hospital on 26 April 1885.[1][7] Her last words were reported as "I tried my best and could try no more".[9][n 2] Elizabeth, the last of the children to be rescued, had suffered severe burns to her legs and died shortly after Ayres.[6]

Funeral

Ayres's body was not taken to Guy's Hospital's mortuary, but was laid in a room set aside for her. The estimated value of the floral tributes came to over £1,000 (about £115,000 as of 2024).[8][10] Ayres was posthumously recognised by the Metropolitan Board of Works-controlled Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire (today the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire), who awarded her father John Ayres a sum of 10 guineas (about £1,210 as of 2024) in her honour.[10] A memorial service for Ayres at St Saviour's Church (now Southwark Cathedral) attracted such a large crowd that mourners were turned away due to lack of standing room, while a collection taken at the memorial service comprised 951 coins, totalling over £7.[3] Ayres was given a large public funeral, attended by over 10,000 mourners.[8][11] Her coffin was carried from her parents' house to her grave in Isleworth Cemetery by a team of 16 firemen, relieving each other in sets of four.[12] The church service was attended by a group of 20 girls, dressed in white, from the village school that Ayres had attended. It had been planned that the girls should follow the coffin to the graveside and sing, but a severe hailstorm prevented this.[13]

Henry and Mary Ann Chandler were buried in Lambeth Cemetery along with the two children who had died in the fire.[6] Edith and Ellen Chandler were accepted by the Orphan Working School in Kentish Town and trained as domestic servants.[6]

Memorial

Shortly after the fire it was decided to erect a monument to Ayres, to be funded by public subscription, and by August 1885 the fund had raised over £100 (about £11,000 as of 2024).[10][12] On 15 August 1885 work began on the memorial. The monument was erected above her grave in Isleworth Cemetery,[14] and was of an Egyptian design inspired by Cleopatra's Needle, which had been raised in central London in 1878.[12][n 3] It took the form of a 14-foot (4.3 m) solid red granite obelisk, and is still today the tallest grave marker in the cemetery.[9] On the front of the obelisk is inscribed:

Sacred to the memory of ALICE AYRES, aged 26 years, who met her death through a fire which occurred in Union Street, Borough, the 24th of April, 1885 A.D.

Amidst the sudden terrors of the conflagration, with true courage and judgement, she heroically rescued the children committed to her charge. To save them, she three times braved the flames; at last, leaping from the burning house, she sustained injuries from the effects of which she died on April 26th 1885.

This memorial was erected by public subscription to commemorate a noble act of unselfish courage.

"Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life."

The right hand side of the monument lists the ten members of the Alice Ayres Memorial Committee, chaired by Rev H. W. P. Richards. The Union Street fire and Ayres's rescue of the children caused great public interest from the outset, and the fire, Ayres's death and funeral, and the fundraising for and erection of the memorial were all reported in detail in the local and national press and throughout the British Empire.[9]

"A secular canonisation"

The British government had traditionally paid little attention to the poor, but in the wake of the Industrial Revolution attitudes towards the accomplishments of the lower classes were changing. The growth of the railways, the mechanisation of agriculture and the need for labour in the new inner-city factories had broken the traditional feudal economy and caused the rapid growth of cities,[16] while increasing literacy rates led to a greater interest in the media and current affairs among ordinary workers.[17] In 1856 the first military honour for bravery open to all ranks, the Victoria Cross, had been instituted, while in 1866 the Albert Medal, the first official honour open to civilians of all classes, was introduced.[18] Additionally, a number of private and charitable organisations dedicated to lifesaving, most prominently the Royal Humane Society (1776) and Royal National Lifeboat Institution (1824), were increasing in activity and prominence, and gave awards and medals as a means of publicising their activities and lifesaving advice.[19]

Painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts and his second wife, designer and artist Mary Fraser Tytler, had long been advocates of the idea of art as a force for social change, and of the principle that narratives of great deeds would provide guidance to address the serious social problems of British cities.[20][n 4] Watts had recently painted a series of portraits of leading figures he considered to be a positive social influence, the "Hall of Fame", which was donated to the National Portrait Gallery;[22][n 5] since at least 1866 he had proposed as a companion piece a monument to "unknown worth", celebrating the bravery of ordinary people.[23]

On 5 September 1887, a letter was published in The Times from Watts, proposing a scheme to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria by means of collecting and commemorating "a complete record of the stories of heroism in every-day life".[24] He cited the death of Alice Ayres as an example of the type of event he proposed to commemorate, and included in his letter a distorted account of Ayres's actions during the Union Street fire.[24]

The roll would be a long one, but I would cite as an example the name of Alice Ayres, the maid of all work at an oilmonger's in Gravel-lane, in April, 1885, who lost her life in saving those of her master's children.

The facts, in case your readers have forgotten them, were shortly these:—Roused by the cries of "Fire" and the heat of the fiercely advancing flames the girl is seen at the window of an upper story, and the crowd, holding up some clothes to break her fall, entreat her to jump at once for her life. Instead she goes back, and reappears dragging a feather bed after her, which, with great difficulty, she pushes through the window. The bed caught and stretched, the girl is again at the window, a child of three in her arms, which with great care and skill she throws safely upon the mattress. Twice again with still older children she repeats the heroic feat. When her turn comes to jump, suffocated or too exhausted by her efforts, she cannot save herself. She jumps, but too feebly, falls upon the pavement, and is carried insensibly to St. Thomas's Hospital, where she dies.— George Frederic Watts, Another Jubilee Suggestion, 5 Sep 1887[24]

Watts had originally proposed that the monument take the form of a colossal bronze figure,[23] but by 1887 was proposing that the memorial take the form of "a kind of Campo Santo", consisting of a covered way and marble wall inscribed with the names of everyday heroes, to be built in Hyde Park.[25][n 6] Watts's suggestion was not taken up,[27] leading Watts to comment that "if I had proposed a race course round Hyde Park, there would have been plenty of sympathisers".[23] However, his high-profile lobbying further raised the already high public awareness of the death of Alice Ayres.[9]

Depiction in literature and art

Emilia Aylmer Blake wrote perhaps the first poem about Ayres, titled Alice Ayres, which she recited at a social gathering in June 1885.[28] Sir Francis Hastings Doyle also wrote a well-received poem in honour of Ayres,[29] as did leading social reformer and women's rights campaigner Laura Ormiston Chant.[9] By the late 1880s Ayres was coming to be seen as a model of British devotion to duty,[9] and her story was told in collections of heroic and inspirational stories for children,[30] including as the first story in F. J. Cross's influential Beneath the Banner,[4] in which Cross remarked that: "She had tried to do her best always. Her loving tenderness to the children committed to her care and her pure gentle life were remarked by those around her before there was any thought of her dying a heroic death. So, when the great trial came, she was prepared; and what seems to us Divine unselfishness appeared to her but simple duty."[7]

In 1890 a series of painted panels by Walter Crane were unveiled in Octavia Hill's Red Cross Hall, 550 yards (500 m) from the site of the Union Street fire.[31][n 7] Inspired by George Frederic Watts's proposals, the panels depicted instances of heroism in everyday life;[32] Watts himself refused to become involved in the project, as his proposed monument was intended to be a source of inspiration and contemplation as opposed to simply commemoration,[20] and he felt that an artistic work would potentially distract viewers from the most important element of the cases, the heroic sacrifices of the individuals involved.[31]

The first of Crane's panels depicted the Union Street fire.[33] It is an idealised image depicting Ayres as the rescued rather than the rescuer, blending religious imagery with traditional 19th-century symbols of British heroism, and bears no relationship to actual events.[34] Ayres, in a long and flowing pure white gown, stands at a first floor window, surrounded in flames and holding a small child. A fireman stands on a ladder and reaches out to Ayres and the child; meanwhile, a sailor in full Royal Navy uniform holds a second child.[9] Although in reality Ayres had been at a much higher level of the building and the heat of the burning oil and gunpowder had made it impossible for the fire brigade to approach the building,[4] by depicting Ayres with the fireman and sailor, widely seen as symbols of British heroism and British strength, Crane's picture further enhanced her growing reputation as a heroic figure.[9] Crane's picture in the Red Cross Hall was itself mentioned in Alice Ayres, a border ballad by National Trust founder Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley published in his 1896 Ballads of Brave Deeds, for which George Frederic Watts wrote the preface.[9][35]

Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice

In 1898 George Frederic Watts was approached by Henry Gamble, vicar of St Botolph's, Aldersgate church in the City of London. St Botolph's former churchyard had recently been converted, along with two smaller adjoining burial grounds, into Postman's Park, one of the largest public parks in the City of London, and the church was engaged in a protracted financial and legal dispute over ownership of part of the park.[36] To provide a public justification for keeping the disputed land as part of the park, and to raise the park's profile and assist in fundraising, the church offered part of the park as a site for his proposed memorial. Watts agreed, and in 1900 the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice was unveiled by Alfred Newton, Lord Mayor of London, and Mandell Creighton, Bishop of London.[37][38] The memorial consisted of a 50-foot-long (15 m) and 9-foot-tall (2.7 m) wooden loggia with a tiled roof, designed by Ernest George, sheltering a wall with space for 120 ceramic memorial tablets.[25]

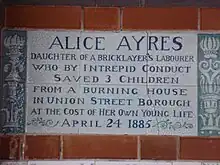

The memorial tablets were handmade and expensive to produce, and at the time of the memorial's unveiling only four were in place. In 1902 a further nine tablets were unveiled, including the memorial to Alice Ayres for which Watts had long lobbied.[39] Made by William De Morgan in the Arts and Crafts style, the green-and-white tablet reads "Alice Ayres, daughter of a bricklayer's labourer who by intrepid conduct saved 3 children from a burning house in Union Street, Borough, at the cost of her own young life April 24, 1885".[40]

Changing attitudes and differing perceptions

Although the public would have been familiar with the concept of a female national heroic figure following the widespread coverage and public admiration of Harriet Newell, Grace Darling and Florence Nightingale, the ongoing coverage of Ayres and her elevation as a national hero was unusual for the period.[3] Ayres was an uneducated working-class woman, who after her death underwent what has been described as "a secular canonisation",[41] at a time when, despite the gradual formal recognition of the contributions of the lower classes, national heroes were generally male and engaged in exploration, the military, religion or science and engineering.[18]

This was a period in which political pressures for social reform were growing. The version of Ayres presented to the public as a woman devoted entirely to duty embodied the idealised British character at the time, while the image of a hard-working but uncomplaining woman who set the welfare of others above her own embodied the idealised vision of the working class presented by social reformers, and the ideal selfless and dedicated woman presented by campaigners for women's rights.[3] At the unveiling of the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice the Lord Mayor, Alfred Newton, had remarked that it was "intended to perpetuate the acts of heroism which belonged to the working classes",[42] while George Frederic Watts, although he was opposed in principle to discrimination based on class and saw the Memorial as being theoretically open to all classes, had remarked that "the higher classes do not or ought not to require reminders or inducements".[42] Watts saw the purpose of his Memorial not as a commemoration of deeds, but as a tool for the education of the lower classes.[42]

Watts's view was shared by others who sought to provide inspirational material on British heroes, and authors writing about Ayres systematically altered the fact that the children rescued were members of her family, instead describing them as the children of her employer.[43] Press reports at the time of the fire described Ayres variously as a "little nursemaid",[5] "a willing, honest, hard-working servant",[5] and a "poor little domestic".[44] As well as Watts's 1887 description of Ayres as "the maid of all work at an oilmonger's",[24] Cross's chapter on Ayres in Beneath the Banner is titled "Only a Nurse Girl!",[4] while Rawnsley called her "the nursemaid in the household".[35] Barrington, writing five years after the fire at the unveiling of Price's panel, acknowledges in a footnote that Ayres was related to the Chandlers,[45] but nonetheless describes her as displaying the "typical English virtues—courage, fortitude, and an unquestioning sense of duty".[46]

While George and Mary Watts and their fellow paternalist social reformers, along with the broadly sympathetic mainstream British press, portrayed Ayres as an inspirational selfless servant to her employer, others had a different view. The left-wing Reynolds's Weekly Newspaper complained that the lack of support for Ayres's family from the state was symbolic of poor treatment of workers as a whole.[43] The pioneering feminist periodical The Englishwoman's Review described their "righteous pride" at Ayres's "instinctive motherhood";[43] on the other hand Young England, a children's story paper with imperialist ideals, said that "there is no sex in self-sacrifice", lauding Ayres as a model of devotion to duty.[43]

Later years

In 1936 the new Labour administration of the London County Council renamed White Cross Street, near the site of the Red Cross Hall and the scene of the Union Street fire, to Ayres Street in tribute to Alice Ayres, a name it retains today.[30] The Chandlers' house at 194 Union Street no longer stands, and the site is occupied by part of the Union House office complex; immediately opposite the site of the fire is the present-day headquarters of the London Fire Brigade.[47]

In popular culture

Alice Ayres came to renewed public notice with the release of the 1997 play Closer by Patrick Marber and the 2004 BAFTA Award- and Golden Globe-winning film Closer based on it starring Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, Jude Law and Clive Owen. A key plot element revolves around the memorial tablet to Ayres at the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Postman's Park, in which it is revealed that the character Jane Jones (played by Portman in the film), who calls herself Alice Ayres for most of the story, has in fact fabricated her name and identity based on the tablet on the memorial,[48][49] which she reads at the time of her first meeting with Dan Woolf (played by Jude Law) near the beginning of the film.[22][50] The park, and the memorial to Ayres, feature prominently in the opening and closing scenes of the film.[51]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ No recorded statements from Alice Ayres other than those given in hospital after the Union Street fire survive. All descriptions of her published in the press were given by neighbours and relatives after her death and in the context of coverage of Ayres as a national hero and model of devotion to duty.[1]

- ↑ Although some press reports at the time stated that Ayres died without regaining consciousness, this is incorrect; she was conscious and lucid while in hospital and gave the authorities a full account of her actions during the fire.[1]

- ↑ Cleopatra's Needle is a 68-foot (21 m) ancient Egyptian obelisk originally erected c. 1450 BC by Thutmose III in Heliopolis. Moved to Alexandria in 12 BC, in 1819 it was given to the people of the United Kingdom by Muhammad Ali as a token of thanks for the British victories at the battles of the Nile and Alexandria, which had ended the invasion of Egypt by the French Directory. Neither the British nor the Egyptian government was prepared to finance the cost of moving it, and it was not actually brought to London until Sir Erasmus Wilson privately financed its transport and installation on the Victoria Embankment in 1878. Despite the name, it has no connection to Cleopatra VII.[15]

- ↑ The idea of inspirational examples as a force for social improvement, as advocated in Samuel Smiles's 1859 Self-Help, was a key tenet of late-19th-century Liberalism and of the settlement movement.[21] The most vocal advocate of this approach was probably the historian James Anthony Froude, who in his Short Studies on Great Subjects had called for biographies that could be given to the lower classes with the injunction "Read that; there is a man—such a man as you ought to be; read it; meditate on it; see who he was and how he made himself what he was, and try to be yourself like him".[20]

- ↑ Owing to National Portrait Gallery acquisition rules, the portraits were not allowed to be exhibited in the NPG until ten years after the death of their subjects, and were housed in the Watts Gallery until the NPG was permitted to display them. Seventeen portraits in total were donated to the NPG as part of Watts's Hall of Fame. The Hall of Fame is now divided between the NPG and Bodelwyddan Castle.[22]

- ↑ In 1902, shortly before his death, Watts would eventually realise his ambition of erecting a giant bronze monument. Physical Energy is a colossal statue of a naked man on horseback shielding his eyes from the sun as he looks ahead of him. Bronze casts of Physical Energy stand at the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town and in Kensington Gardens, London.[26]

- ↑ The Red Cross Hall has no relationship with the International Committee of the Red Cross; it was built on Redcross Way in Southwark, as part of a number of cottages in the area planned by Hill.[31] The parallel White Cross Street has since been renamed Ayres Street.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Price 2008, p. 57

- 1 2 Price, John (2010). "Alice Ayres". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/100744. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Price 2008, p. 62

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cross 1894, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Heroine in Humble Life". The Star (Christchurch). 3 July 1885. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Price 2008, p. 58

- 1 2 3 Cross 1894, p. 14

- 1 2 3 "Unsurpassable Bravery: A great deed recalled". Sydney Mail. 10 February 1909. p. 25. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Price 2008, p. 60

- 1 2 3 UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ "Servants Who Have Died For Their Employers". The Star (Christchurch). 11 November 1899. p. 3. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- 1 2 3 Price 2008, p. 59

- ↑ "Funeral of Alice Ayres". Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. 10 May 1885.

- ↑ "Proposed Extension of Isleworth Riverside Conservation Area". Isleworth & Brentford Area Planning Committee. London Borough of Hounslow. 19 November 2006. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Curl, James Stevens (2005). The Egyptian Revival. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 333. ISBN 0-415-36119-2. OCLC 57208695.

- ↑ Cunningham, William (1968). The Growth of English Industry and Commerce in Modern Times. Vol. 2. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 613. ISBN 0-7146-1296-0.

- ↑ West, E. G. (1985). Joel Mokyr (ed.). The Economics of the Industrial Revolution. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 190. ISBN 0-86598-154-X.

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 65

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 66

- 1 2 3 Price 2008, p. 41

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 42

- 1 2 3 Sandy Nairne, in Price 2008, p. 7

- 1 2 3 Price 2008, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 George Frederic Watts (5 September 1887). "Another Jubilee Suggestion". Letters to the Editor. The Times. London. col B, p. 14.

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 21

- ↑ Baker, Margaret (2002). Discovering London Statues and Monuments. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 0-7478-0495-8.

- ↑ "Valhalla for Humble Heroes: Artist Watts's Scheme to Perpetuate Deserving Deeds – Public Gallery of Life Savers' Portraits". New York Times. 16 October 1898. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ "Mrs Ashley's Entertainment". The Era. 13 June 1885.

- ↑ Andrews, William (1888). North Country Poets: Poems and biographies of natives or residents of Northumberland, Cumberland, Westmoreland, Durham, Lancashire and Yorkshire. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co. p. 57. OCLC 37163256.

- 1 2 3 Price, John (2007). "Heroism in Everyday Life: the Watts Memorial for Heroic Self Sacrifice". History Workshop Journal. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 63 (63): 254–278. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbm013. ISSN 1363-3554.

- 1 2 3 Price 2008, p. 39

- ↑ "Religion and Temperance". Brisbane Courier. 7 February 1891. p. 6. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Barrington 1896, p. 313

- ↑ The murals are discussed in detail in chapter two of, John Price, Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian (Bloomsbury: London, 2014)

- 1 2 Rawnsley, H. D. (1896). Ballads of Brave Deeds. London: J. M. Dent. OCLC 9725182.

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 14

- ↑ "The Postmen's Park and Cloister". News. The Times. London. 31 July 1900. col E, p. 2.

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 17

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 22

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 50

- ↑ Perry, Lara (2006). History's Beauties. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. p. 163. ISBN 0-7546-3081-1. OCLC 60697164.

- 1 2 3 Price 2008, p. 68

- 1 2 3 4 Price 2008, p. 69

- ↑ "Heroism of a Servant Girl". Tuapeka Times. 24 June 1885. p. 5. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Barrington 1896, p. 316

- ↑ Barrington 1896, p. 319

- ↑ "London Fire Brigade Headquarters" (PDF). London Fire Brigade. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Innes, Christopher (2002). Modern British Drama (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 432. ISBN 0-521-01675-4. OCLC 216904040.

- ↑ Burgess, Kaya (12 June 2009). "Leigh Pitt, who died saving boy, added to 'everyday heroes' memorial". The Times. London.

- ↑ "London's 10 best picnic spots". thelondonpaper. News International. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ↑ Price 2008, p. 11

Bibliography

- Barrington, Russell (Mrs) (1896). A Retrospect and Other Articles. London: Osgood, McIlvaine & Co. OCLC 265434178.

- Cross, F. J. (1894). Beneath the Banner: Being narratives of noble lives and brave deeds. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 266994986.

- Price, John (2014). Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-0665-0.

- Price, John (2008). Postman's Park: G. F. Watts's Memorial to Heroic Self-sacrifice. Studies in the Art of George Frederic Watts. Vol. 2. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-1-8.