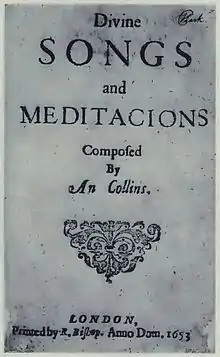

An Collins (fl. 1653) is the otherwise unknown poet credited with the authorship of Divine Songs and Meditacions, a collection of poems and prose meditations published in London in 1653.

Background and controversy

Nothing is known of An Collins apart from what can be gleaned from Divine Songs and Meditacions, a collection of poems and meditations published in London by R. Bishop in 1653 "compiled by An Collins."

Most commentators have assumed "An" to be a variant of "Anne" or "Ann." Additionally, there are indications within the texts themselves that Collins was a woman. Some scholars have speculated that "An" could be a pseudonym, or "An" could even refer to the indefinite article "an", indicating that the poet's first name was unknown to the publisher.[1] The current critical consensus, however, is that An Collins wrote as a woman.[2]

From further textual evidence, scholars have developed a likely partial description of An Collins. From certain references in "To the Reader", the preface, "The Discourse", and elsewhere, some commentators have speculated that she may have lived in the country rather than the city. It also seems clear that she had health issues or physical challenges that restricted her ability to move freely and that she lived with chronic pain,[3] as when she writes "I inform you, that by divine Providence, I have been restrained from bodily employments, suting with my disposicion, which enforced me to a retired Course of life" ("To the Reader," ll. 1-3).

She does not mention a family, but rather a faith community.[4]

Divine Songs and Meditacions

The individual texts in Divine Songs and Meditacions range in style and subject. Most deal directly with religious matters, but there are several pieces, notably "A song composed in time of the Civill Warr, when the wicked did much insult over the godly," that focus on the political environment of England during the English Civil War.

Collins' style has interested scholars and there has been some work done analyzing the metric forms of Divine Songs, such as the usage of Rime royal in The Preface.[5] Collins' collection also has historical significance: it is one of the first collected volumes of women's poetry from the seventeenth century, and it provides a glimpse into the life of a woman writer, as well as insight into the political, social, and religious landscape of seventeenth-century England.[6] Several critics discuss her work in the context of the seventeenth-century tradition of the spiritual autobiography[2][7]

Religious and political views

There has been considerable writing on the subject of An Collins' political and religious beliefs. Early commentators describe her as "a quietist devotional writer," withdrawn from the world.[2] More recent commentators, however, have found a more complicated writer.

Ostovich and Sauer write that, "An Collins' religious beliefs have been variously defined as anti-Puritanical, Calvinist, Catholic, anti-Calvinist, and Quaker..."[1] All of these aspects have been seen in Divine Songs. The Discourse presents a standard primer on Protestant teachings, and its focus on sin has led some critics to speculate that the author may have been a Calvinist. However, the general lack of focus on predestination in the collection makes this possibility less persuasive.[4] Some scholars have put forth the idea that Divine Songs and Meditacions demonstrates a tendency towards Catholicism. In particular, Collins' "meditacions" appear to follow the "Short Method for Meditation" put forth by the Catholic Bishop of Geneva, Francis de Sales, author of the popular Introduction a la Vie Devote, which had three separate English editions by 1613.[5] Ultimately, there is no critical consensus about which tradition of Christianity Collins likely professed.

As with her religious beliefs, there has also been speculation about Collins' political positions. She has been variously described as "critical of sectaries and Independents, pro-Commonwealth, opposed to the radical wing of Parliament, anti-Commonwealth, and Royalist."[1]

Legacy and influence

The largest barrier to Collins' influence has been the limited availability of her work. There is only one copy of the original work extant, located at the Huntington Library, which would indicate limited circulation at the time of publication. However, there have been three modern editions to date: Stewart’s facsimile edition (1961),[8] Gottlieb’s annotated and modernized text (1996),[9] and a newer facsimile edition (2003) introduced by Robert C. Evans,[10] so Divine Songs and Meditacions has become available to new generations of readers and scholars.[11]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Ostrovich and Sauer 2004, p. 387.

- 1 2 3 Howard 2005

- ↑ Evans 2003, p. xiii

- 1 2 Gottlieb 2004, Collins, An.

- 1 2 Greer et al. 1988, p. 150

- ↑ Evans 2003, p. xi

- ↑ Cunnar 1993, p. 49

- ↑ Collins, An. Divine Songs and Meditacions. 1653. The Augustan Reprint Society. Selected, with an Introduction, by Stanley N. Stewart. Publication Number 94. Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, 1961. (Project Gutenberg)

- ↑ Collins, An. Divine songs and meditacions. Ed. Sidney Gottlieb. Tempe, Ariz. : Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1996. (Internet Archive)

- ↑ Evans, Robert C., Ed. An Collins. The Early Modern Englishwoman: a Facsimile Library of Essential Works, Printed writings, 1641-1700 Series II, Part 2; Volume I. Aldershot, England/Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003.

- ↑ See, for example, Howard 2014.

References

- Cunnar, Eugene R. "An Collins" in Hester, M. Thomas (ed.), Seventeenth-Century British Nondramatic Poets: Third Series, Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol 131. Detroit: Gale, 1993. ISBN 9780810353909 ISBN 0810353903 OCLC 28183727

- Evans, Robert C. The Early Modern Englishwoman: a Facsimile Library of Essential Works, Series II, Volume I, An Collins. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003.

- Gottlieb, Sidney. "Collins, An (fl. . 1653)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP, 2004.

- Graham, Elspeth, et al. Her Own Life: Autobiographical Writings by Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen. New York : Routledge, 1989. ISBN 9780203358962 ISBN 9780415016995 OCLC 252921777 (Open access, Internet Archive)

- Greer, Germaine, et al. Kissing the Rod: An Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Women's Verse. London : Virago, 1988.

- Howard, W. Scott. "Of Devotion and Dissent: An Collins’s Divine Songs and Meditacions (1653). Discoveries in Renaissance Culture 22.1 (2005).

- Howard, W. Scott, Ed. An Collins and the historical imagination. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. ISBN 9781472418470 ISBN 1472418476 OCLC 866617396

- Ostrovich, Helen, and Elizabeth Sauer. Reading Early Modern Women; An Anthology of Texts in Manuscript and Print, 1550-1700. New York : Routledge, 2004. ISBN 9780415966450 ISBN 9780415966467 OCLC 52047251

Further reading

- Brydges, Sir Egerton. Restituta; or, Titles, Extracts, and Characters of Old Books in English Literature, Revived. 4 Vols. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1814-1816.

- Dyce, Alexander, Specimens of British Poetesses. London: T. Rodd, 1825.

- Gottlieb, Sidney. "An Collins and the Experience of Defeat." Representing Women in Renaissance England. Ed. Claude J. Summers and Ted-Larry Pebworth. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. 216-26.

- Griffith, A. F. Bibliotheca Anglo-Poetica. London: Thomas Davison, 1815.

- Howard, W. Scott. "An Collins and the Politics of Mourning." Speaking Grief in English Literary Culture, Shakespeare to Milton. Ed. Margo Swiss and David A. Kent. Pittsburgh: Duquesne UP, 2002. 177-96.

- Morrissey, Mary. "What An Collins was Reading." Women’s Writing 19 (2012), 467-86.

- Price, Bronwen. "'The Image of Her Mind': The Self, Dissent and Femininity in An Collins’s Divine Songs and Meditacions." Women’s Writing 9.2 (2002): 249-65.

- Wilcox, Helen. "The finenesse of Devotional Poetry: An Collins and the School of Herbert." An Collins and the Historical Imagination. Ed. by W. Scott Howard. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014, pp. 71-86.

- Wilcox, Helen. "‘Scribbling under so Faire a Coppy’: The Presence of Herbert in the Poetry of Vaughan’s Contemporaries." Scintilla 7 (2003): 185-200.