Ananias Dare | |

|---|---|

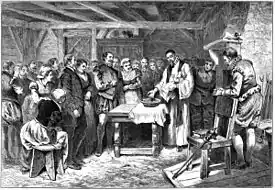

Baptism of Virginia Dare lithograph with Ananias Dare in the center (1880) | |

| Born | Ananias Dare c. 1560 |

| Died | After 27 August 1587, presumably before 18 August 1590 (aged 27–30) unknown |

| Occupation | unknown |

| Known for | Colonist of the Lost Roanoke Colony |

| Spouse | Eleanor White |

| Children | Virginia Dare |

Ananias Dare (c. 1560 – 1587, legal death) was a colonist of the Roanoke Colony of 1587. He was the husband of Eleanor White, whom he married at St Bride's Church[1] in London, and the father of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America. The details of Dare's death are still unknown.

Personal life

He was the father of Virginia Dare, whose birth on August 18, 1587, was the first recorded to English parents on the continent of North America.

Very little is known of Dare other than the birth of his child, but his father-in-law, John White, was appointed Governor during the second attempt to settle Sir Walter Raleigh's Roanoke colony in 1587. White also accompanied the 1585 to 1586 expedition, led by Richard Grenville at sea and Ralph Lane on land. The illustrations White made during his stay at Roanoke were published in 1590 along with Thomas Harriet's "A Brief and True Report".

English descendants

According to the Index to Acts of Administration in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury 1596–1608, Ananias had a son by the name of John who was placed into the custody of a John Nokes of London in April 1594 and "decreed" his son in June 1597. Both John Nokes and a certain Robert Satchfield had originally applied to the Canterbury Court for the guardianship in 1594. This Robert Satchfield may be the same Robert Sackville, 2nd Earl of Dorset. The following is an exact quote from the abbreviated entry:

- Dare, Ananias, St. Bride, Lond. To Jn. Nokes, k., dur. min. of Jn. D., s. (by Decree), (prev. Gnt. Apr 1594, p. 95), Jun 1597, p. 213

- Translation ... "dur. min." means: "during minority" and is usually written: "durante minore aetate"; and basically concerns the "minor person of", and then the name. "Aetate", which means "age", is understood and can, as in this case, subtly refer to a person's estate. Such "double talk" is typical in Latin with things alluded to having an outward meaning as well as an additional "subtle" meaning "reserved" for those of an ominous "inner circle".

So that immediately the children of the missing persons from the Colony were placed into respective guardianships, and all of them were eventually declared dead by the Prerogative or other appropriate court.

The external link below indicates that Ananias and his wife were married in the same church as that mentioned in the quote above, St Bride's, London, and a carving of Virginia Dare's bust is situated above the font of the church.

In Frances Rose-Troup, John White, the Patriarch of Dorchester and the Founder of Massachusetts (1930), the author mentions John White who appears to be the son of the same above-mentioned John White. There, the author also gives mention of a certain George Dier (1579–1672) and his relationship to the Rev. John White. In Charles Edward Banks, The Planters of the Commonwealth (1930, 1st edition) there is an important mention of a vessel by the name of Mary & John that the same above-mentioned Rev. John White sponsored from Plymouth, England to Dorchester on March 20, 1630. On that vessel's ship's list are a mention of a John Drake, close relation of Sir Francis Drake, as well as that of a George Dyer – the same George Dier that is mentioned in Rose-Troup.

Roanoke Colony

In her 2000 book Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony, anthropologist Lee Miller speculates that Ananias Dare and the other members of the Roanoke Colony were religious Separatists who left England at a time when the political climate in England was dangerous for such religious dissidents. She suggests that this might be why the colonists, two of whom were pregnant women and several of whom were parents with young children, were willing to undertake the dangerous journey to Roanoke Island with low supplies and at a time England was on the verge of war with Spain. The colonists, including the women, signed a petition urging White to return to England for supplies, even though he was reluctant to leave his daughter and granddaughter. Miller suggests that this democratic action would have been typical of a religious Separatist group.[2]

John White left the group on August 27, 1587, and returned three years later, only to find the colony deserted.

Historical explanations

John Smith and other members of the Jamestown Colony sought information about the fate of the colonists in 1607. One report indicated that the Lost Colonists took refuge with friendly Chesapeake Indians, but Chief Powhatan claimed his tribe had attacked the group and killed most of the colonists. Powhatan showed Smith certain artifacts he said had belonged to the colonists, including a musket barrel and a brass mortar. The Jamestown Colony received reports of some survivors of the Lost Colony and sent out search parties, but none were successful. Eventually they determined they were all dead.[3]

However, in her 2000 book Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony, Miller postulated that some of the Lost Colony survivors sought shelter with a neighboring Indian tribe, the Chowanoc, that was attacked by another tribe, identified by the Jamestown Colony as the "Mandoag," but whom Miller thinks were actually the Eno, also known as the Wainoke. Survivors were eventually sold into slavery and held captive by differing bands of the Eno tribe, who, Miller wrote, were known slave traders. Miller wrote that English settlers with the Jamestown Colony heard reports in 1609 of the captive Englishmen, but the reports were suppressed because they had no way to rescue the captives and didn't want to panic the Jamestown colonists. William Strachey, a secretary of the Jamestown Colony, wrote in his The History of Travel Into Virginia Britania in 1612 that, at the Indian settlements of Peccarecanick and Ochanahoen, there were reportedly two story houses with stone walls. The Indians supposedly learned how to build them from the Roanoake settlers.[4] There were also reported sightings of European captives at various Indian settlements during the same time period.[5] Strachey wrote in 1612 that four English men, two boys, and one girl had been sighted at the Eno settlement of Ritanoc, under the protection of a chief called Eyanoco. The captives were forced to beat copper. The captives, he reported, had escaped the attack on the other colonists and fled up the Chaonoke river, the present-day Chowan River in Bertie County, North Carolina.[4][6]

Possible descendants

Miller reports the following: The Chowanoc tribe was eventually absorbed into the Tuscarora. The Eno tribe was also associated with the Shakori tribe and was later absorbed by the Catawba or the Saponi tribes. From the early 17th century to the middle 18th century European colonists reported encounters with gray-eyed American Indians or with Welsh-speaking Indians who claimed descent from the colonists.[7] In 1669 a Welsh cleric named Morgan Jones was taken captive by the Tuscarora. He feared for his life, but a visiting Doeg Indian war captain spoke to him in Welsh and assured him that he would not be killed. The Doeg warrior ransomed Jones and his party and Jones remained with their tribe for months as a preacher.[8] In 1701, surveyor John Lawson encountered members of the Hatteras tribe living on Roanoke Island who claimed some of their ancestors were white people. Lawson wrote that several of the Hatteras tribesmen had gray eyes.[9] Some present-day American Indian tribes in North Carolina and South Carolina, among them the Coree and the Lumbee tribes, also claim partial descent from surviving Roanoke colonists.

Film and literary references

Ananias Dare was played by Adrian Paul in the film Wraiths of Roanoke.

See also

Notes

- ↑ St Bride's: American Connections Archived 2011-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 51

- ↑ The Lost Colony: Roanoke Island, NC ~ Packet by Eric Hause: Articles about the Outer Banks NC and the Mainland

- 1 2 Stick (1983), p. 222

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 250

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 242

- ↑ Miller (2000), pp. 257, 263

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 257

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 263