| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

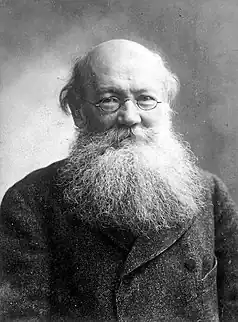

Anarchist criminology is a school of thought in criminology that draws on influences and insights from anarchist theory and practice. Building on insights from anarchist theorists including Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Peter Kropotkin, anarchist criminologists' approach to the causes of crime emphasises what they argue are the harmful effects of the state. Anarchist criminologists, a number of whom have produced work in the field since the 1970s, have critiqued the political underpinnings of criminology and emphasised the political significance of forms of crime not ordinarily considered to be political. Anarchists propose the abolition of the state; accordingly, anarchist criminologists tend to argue in favour of forms of non-state justice. The principles and arguments of anarchist criminology share certain features with those of Marxist criminology, critical criminology and other schools of thought within the discipline, while also differing in certain respects.

Background and precursors

Anarchism is not a single ideology but rather a tradition that encompasses a variety of belief systems and practices, united by a belief that the state is coercive, exploitative, and destructive, and by advocacy on behalf of non-hierarchical organisational forms and mutual aid.[1] Anarchism is anti-authoritarian: whereas ideologies such as Marxism and feminism oppose particular forms of power, anarchists oppose power as such, including capitalism, the state, organised religion and patriarchy, which they see as interwoven with one another.[2][3][4] Accordingly, anarchism questions the conventional wisdom produced by these forms of power, including ideas about universality, and pursues pluralism and multiplicity in the epistemic and aesthetic domains.[5][6] "Anarchy", for anarchists, means a society without rulers, but not one without order.[7]

The roots of anarchist criminology lie in the critiques of law and legality formulated by classical anarchists including Mikhail Bakunin, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, William Godwin, Peter Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Max Stirner, each of whom envisioned forms of social order that would, in the absence of the state, maximise individual freedom and encourage self-organisation.[1][8][9][10] Kropotkin developed an expansive account of the sociology of law, in which he argued that aspects of existing legal structures serve primarily to protect the wealthy or to protect the state, and was among the first criminologists to examine crime's social causes.[10] Kropotkin argued that law, especially law protecting private property and the state, was to blame for sustaining criminality and generating social pathologies.[11] Rather than preventing crime, Kropotkin argued that punishment only brings out the worst in people and enhances the power of the state over people's lives.[11] Kropotkin thought that most crime would vanish following the abolition of private property and the replacement of profit and competition by cooperation and human need as society's guiding principles.[11] In this framework, alternative notions of social justice and alternative forms of solidarity would supersede existing structures of criminal justice and the rule of law as tools for mitigating anti-social behaviour.[11]

Jeff Shantz and Dana M. Williams argue that "grappling with an anarchist criminology means engaging more directly and more fully with the history of anarchist writings on crime and social order",[12] and that Proudhon's work in particular anticipates the insights of left realist criminology, while also transcending it by maintaining a critical attitude toward state power.[13] Shantz and Williams argue that Proudhon's thought is "an antidote to the authoritarian, mythic conceptions of justice presented by social contract theory and mainstream criminology but also the limited and constrained notions of justice posited by statist critical theory and socialism"[14] and a precursor to peacemaking criminology and theories of restorative justice.[15]

The anarchist criminologist Jeff Ferrell also identifies the anarcho-syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as a precursor of anarchist criminology: in the United States in the early 20th century the IWW identified "law and order" as a form of power instantiated by the ruling class at the expense of the working class, and developed the tactic of the "on the job strike", in which workers stringently obey rules and regulations in order to slow work.[10] Ferrell argues that criminologists can draw on the anarchist tradition in order to oppose "an increasingly authoritarian social order".[16] Within this framework, anarchist perspectives aid in understanding forms of both authority and resistance.[16]

Overview

Causes of crime

Anarchist criminologists hold that crime is caused by structures of oppression and domination.[7] Accordingly, their priority is often to critique these structures, with the goal of replacing them, rather than to develop detailed analyses of how they cause crime.[7]

Anarchist criminologists have theorised the law as a "state protection racket", arguing that phenomena such as speed traps and seizure laws are similarly backed by the threat of violence.[17] They argue that these and similar phenomena are a feature of all legal systems—found in democracies as much as in dictatorships—and that their ubiquity indicates that law does not protect from harm, but is itself a form of harm.[18]

Anarchist criminologists also emphasise the "definitional" role of criminal justice systems, through which such systems are empowered to define certain behaviours as criminal, and argue that many acts considered criminal are only deemed so because they are associated with less powerful social groups or with efforts to dislodge existing power structures.[18]

Ferrell argues that anarchist criminology is a critique of the way that human relationships become submerged in, and immobilised by, structures of legal authority.[6][19] Anarchist criminology contends that law solidifies and reproduces existing structures of power, thereby placing limitations on possible social relations and exacerbating crime and violence.[4]

Approach to the discipline

Anarchist criminology argues that the state is not politically neutral, and that criminology cannot be neutral either. Within this framework, anarchist criminologists argue that while much criminology takes the side of the powerful, other traditions in criminology side with the oppressed and exploited.[20]

Anarchist criminologists argue that state law and criminalisation are inherently political, so acts of crime are by extension always imbued with political significance.[21] As such, anarchist criminology calls for close attention to be paid to criminal (or criminalised) behaviour such as graffiti writing, "obscene" artistic and musical performances, pirate radio broadcasts, illegal strikes, shoplifting, drug use and hacking,[22] and finds forms of political resistance in behaviours and lifestyles commonly considered criminal.[23]

Ferrell describes anarchist criminology as invested in a process of demystification through which the epistemologies of certainty, truth and justice that are used to justify authority are called into question.[24][25] Ferrell expresses hope that this process of "dismantling" the mythologies surrounding the law will "contribute to a more general disrespect for law and authority" by calling law's legitimacy into question.[26]

Ferrell argues that instead of adhering to a single masterplan, anarchist criminology is characterised by a "spirit of eclectic inclusivity" and an embrace of "fluid communities of uncertainty and critique."[27] He also proposes that anarchist criminological orientations "can serve not as some rigid corrective, nor competing paradigm, but as analytic sparks within an already lively alternative criminology."[16] Ferrell argues that anarchist criminology does not purport "to incorporate reasoned or reasonable critiques of law and legal authority," but rather argues that social change requires "unreasonable" approaches.[28]

Practical implications

Anarchist criminologists propose the replacement of existing legal systems with decentralised, negotiated, participatory justice.[29] Such a system would, it is thought, encourage individuals to accept responsibility for their behaviour by reminding them of their connections to others in society.[29] Anarchist criminology argues that if law must exist, its function must be transformed so that instead of protecting private property, social privilege and state power, it would ensure tolerance and diversity.[19][30] Anarchist criminology tends to favour holistic transformative justice approaches over restorative justice, which it tends to argue is too beholden to the existing criminal justice system.[31]

Many anarchist criminologists endorse prison abolition, arguing that prisons encourage recidivism and should be replaced by efforts to rehabilitate offenders and reintegrate them into communities.[32] Ferrell argues that anarchist criminology must oppose moral entrepreneurs and associated "wars" (the War on Drugs, War on Gangs, etc.), which he argues "operate as well-planned exercises in victimization and blame, deflecting the public gaze from those in authority and toward those least able to resist it."[33] Declaring "war" in this way, Ferrell argues, "exacerbates and perpetuates the very problems it claims to address" and leads to heightened violence.[18]

Larry Tifft and Dennis Sullivan argue that advocates of anarchist criminology "are interested not only in pointing to those persons, groups, organizations, and nation-states that deny people their needs in everyday life but also in fostering social arrangements that alleviate pain and suffering by providing for everyone's needs."[34] Tifft and Sullivan argue that "an anarchist needs-based criminology should transcend criminology",[35] resulting in "changes in our daily lives: interacting with your intimate partner differently, living with your children differently; collaborating with coworkers differently; helping children develop their talents differently; making collective investment decisions differently; and making self-development decisions differently."[36]

Relation to other schools of criminological thought

The core principles of anarchist criminology are linked to those of abolitionism, critical race theory, left realism, peacemaking criminology and restorative justice.[11][37] Anarchist criminology also informs new criminology, labeling theory, postmodern criminology and cultural criminology.[38] Stuart Henry and Scott A. Lukas argue that anarchist criminology is related to constitutive criminology, cultural criminology, left realism and critical race theory, all of which they argue represent divergences from a single perspective but which also have in common the themes of peacemaking criminology and restorative justice.[39] Peacemaking criminology, which argues that violent responses to social problems result in further violence and seeks to develop ways to transform violent relationships into safe and respectful relationships, also emerged from work in anarchist criminology.[40] Ferrell also identifies anarchist criminology as a type of newsmaking criminology.[41]

Anarchist criminology shares with postmodern criminology the belief that domination can work through structures of information and knowledge.[29] It also shares with Marxist criminology the view that crime has its origins in an unjust social order and that a radical transformation of society is desirable.[42] Unlike Marxists, however, who propose that capitalism be replaced with state socialism, anarchists reject all hierarchical or authoritarian structures of power.[42] Anarchist criminology is associated with critical criminology, though Anthony J. Nocella II argues that differences between the two schools reflect divergences between anarchism and Marxism: anarchist criminology foregrounds anti-authoritarianism, while critical criminology shares with Marxism a willingness to accept authority when exercised by the proletariat.[9] While many critical criminologists argue that state law in many cases reproduces economic inequality, patriarchy and racism, anarchist criminologists go further by arguing that state law is inherently harmful to people and society even when it is not overtly discriminatory.[43]

In his case study of graffiti writing, Ferrell argues that anarchist criminology must combine aspects of interactionism and political or economic criminology, as "we cannot understand the nature of crime without understanding both its immediate construction out of social interaction and its larger construction through processes of political and economic authority."[44][45] Ferrell proposes that this entails "that anarchist criminologists must look up and down at the same time—that is, must pay attention to the subtleties of legal and political authority, the nuances of lived criminal events, and the interconnections between the two."[46] However, while anarchist criminologists "look up" disrespectfully at hierarchical and authoritarian power structures, they "look down and around at the lived experience of criminality ... respectfully—not with respect for any and all criminal acts, but for the possibilities of meaning that are embedded in them."[46]

Ferrell also writes:

Anarchist criminology certainly incorporates the sort of "visceral revolt" that characterizes anarchism itself, the passionate sense of "fuck authority," to quote the old anarchist slogan, the comes from being shoved around by police officers, judges, bosses, priests, and other authorities one time too many. Moreover, anarchists would agree with many feminist and postmodernist theorists that such visceral passions matter as methods of understanding and resistance outside the usual confines of rationality and respect. But anarchist criminology also incorporates a relatively complex critique of state law and legality which begins to explain why we might benefit from defying authority, or standing "against the law."[47]

Anarchist criminologists

Prominent anarchist criminologists since the 1970s have included Randall Amster, who has explored anti-authoritarian forms of conflict resolution in anarchist communities;[10] Bruce DiCristina, whose work draws on the thought of Paul Feyerabend in order to critique criminology and criminal justice;[48] Jeff Ferrell, whose work examines the relationships between legal authority, resistance and criminality;[10][49] Harold Pepinsky, who in 1978 published an article on "communist anarchism as an alternative to the rule of criminal law", which introduced an approach that later came to be known as peacemaking criminology;[10][49] Dennis Sullivan;[9][10][49] and Larry Tifft, who argued for the replacement of state law with a face-to-face form of justice grounded in humans' needs.[9][10][49] David Gil and Richard Quinney have also published similar critiques and proposals to those that feature in anarchist criminology.[36]

Evaluation

Eugene McLaughlin argues that anarchist criminology furnishes criminologists with "an uncompromising critique of law, power and the state; the promise of un-coercive social relationships; the possibility of alternative forms of dispute settlement and harm reduction; a form of political intervention that may be appropriate to an increasingly complex and fragmented world where conventional forms of politics are becoming increasingly redundant; [and] the basis to develop both libertarian and communitarian criminologies."[11] Michael Welch argued in 2005 that

although its application to the study of lawlessness remains limited to a handful of works, anarchist criminology offers the field a valuable framework for deconstructing the state, its authority, and its machinery of repressive social control, as well as the resistance it evokes .... Anarchist criminology has the potential to further advance critical penology by offering a fluid approach to law and justice, inviting scholars to incorporate an array of sociological concepts into their analyses of the state, the criminal justice system, and the corrections apparatus.[50]

Stanislav Vysotsky argues that anarchist criminology's emphasis on restorative justice, as a set of methods applied after crimes or violations of norms have occurred, has resulted in it lacking accounts of how to prevent crime, and that militant anti-fascism, understood as an unorthodox form of policing, can serve as a model for such a preventive approach.[51] Such methods, Vysotsky suggests, are in keeping with the central tenets of anarchism, and so "represent a challenge to the pacifist orientation of anarchist criminology".[52] Anarchist criminology has also been criticised for its perceived romantic idealism, conceptual confusion, lack of a theoretical foundation for its opposition to punishment, and lack of a practical strategy for dealing with dangerous individuals.[53]

Notes

- 1 2 McLaughlin 2013, p. 8.

- ↑ Ferrell 1994, pp. 161–2.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, p. 160.

- 1 2 Ferrell 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, pp. 161–2.

- 1 2 Ferrell 1994, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 Lanier & Henry 2010, p. 371.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 3 4 Nocella 2015, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ferrell 2010, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McLaughlin 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Shantz & Williams 2013, p. 73.

- ↑ Shantz & Williams 2013, p. 70.

- ↑ Shantz & Williams 2013, pp. 71–2.

- ↑ Shantz & Williams 2013, pp. 94–5.

- 1 2 3 Ferrell 1994, p. 161.

- ↑ Ferrell 2010, pp. 43–4.

- 1 2 3 Ferrell 2010, p. 44.

- 1 2 Ferrell 1996, p. 187.

- ↑ Nocella, Seis & Shantz 2018, p. 2.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, p. 17.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, pp. 196–7.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, pp. 189–90.

- ↑ Ferrell 1994, p. 165.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, p. 191. See also Ferrell (1994, pp. 165–6).

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, p. 18.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Lanier & Henry 2010, p. 372.

- ↑ Ferrell 1994, pp. 162–3.

- ↑ Nocella, Seis & Shantz 2018, p. 3.

- ↑ Ferrell 2010, p. 45.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, p. 192.

- ↑ Tifft & Sullivan 2018, p. 259.

- ↑ Tifft & Sullivan 2018, p. 268.

- 1 2 Tifft & Sullivan 2018, p. 267.

- ↑ Lanier & Henry 2010, p. 371, 376.

- ↑ Ferrell 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ Henry & Lukas 2009, pp. xxxiv–xxxv.

- ↑ Ferrell 2010, pp. 45–6.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, p. 191.

- 1 2 Ugwudike 2015, p. 94.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, p. 15.

- ↑ Ferrell 1996, p. 188.

- ↑ Ferrell 1994, p. 163.

- 1 2 Ferrell 1996, p. 189. See also Ferrell (1994, pp. 164–5)

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Ferrell 2018, pp. 13–14. For further discussion of DiCristina see Ferrell (1995).

- 1 2 3 4 Ferrell 2018, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Welch 2005, p. 31.

- ↑ Vysotsky 2015, p. 235–6.

- ↑ Vysotsky 2015, p. 249.

- ↑ Lanier & Henry 2010, p. 380.

References

- Ferrell, Jeff (1994). "Confronting the Agenda of Authority: Critical Criminology, Anarchism, and Urban Graffiti". In Barak, Gregg (ed.). Varieties of Criminology: Readings from a Dynamic Discipline. Praeger Publishing. pp. 161–178.

- Ferrell, Jeff (1995). "Anarchy Against the Discipline". Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture. 3 (4): 86–91. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019.

- Ferrell, Jeff (1996). Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality. Northeastern University Press.

- Ferrell, Jeff (2010). "Anarchist Criminology". In Cullen, Francis T.; Wilcox, Pamela (eds.). Encyclopedia of Criminological Theory. SAGE Publishing. pp. 42–46. doi:10.4135/9781412959193.n11. ISBN 9781412959186.

- Ferrell, Jeff (2018). "Against the Law: Anarchist Criminology". In Nocella, Anthony J. II; Seis, Mark; Shantz, Jeff (eds.). Contemporary Anarchist Criminology: Against Authoritarianism and Punishment. Peter Lang. pp. 11–21.

- Henry, Stuart; Lukas, Scott (2009). "Introduction". In Stuart, Henry; Lukas, Scott (eds.). Recent Developments in Criminological Theory: Toward Disciplinary Diversity and Theoretical Integration. Ashgate Publishing. pp. xiii–xxviii.

- Lanier, Mark M.; Henry, Stuart (2010). Essential Criminology (3rd ed.). Westview Press.

- McLaughlin, Eugene (2013). "Anarchist Criminology". In McLaughlin, Eugene; Muncie, John (eds.). The SAGE Dictionary of Criminology (3rd ed.). SAGE Publishing. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781446271766.

- Nocella, Anthony J. II (2015). "Anarchist Criminology Against Racism and Ableism and for Animal Liberation". In Nocella, Anthony J. II; White, Richard J.; Cudworth, Erika (eds.). Anarchism and Animal Liberation: Essays on Complementary Elements of Total Liberation. McFarland & Company. pp. 40–58.

- Nocella, Anthony J. II; Seis, Mark; Shantz, Jeff (2018). "Introduction: The Rise of Anarchist Criminology". In Nocella, Anthony J. II; Seis, Mark; Shantz, Jeff (eds.). Contemporary Anarchist Criminology: Against Authoritarianism and Punishment. Peter Lang. pp. 1–8.

- Shantz, Jeff; Williams, Dana M. (2013). Anarchy and Society: Reflections on Anarchist Sociology. Brill Publishers.

- Tifft, Larry; Sullivan, Dennis (2018) [2006]. "Needs-Based Anarchist Criminology". In Henry, Stuart; Lanier, Mark M. (eds.). The Essential Criminology Reader. Routledge. pp. 259–277.

- Ugwudike, Pamela (2015). An Introduction to Critical Criminology. Policy Press.

- Vysotsky, Stanislav (2015). "The Anarchy Police: Militant Anti-Fascism as Alternative Policing Practice". Critical Criminology. 23 (3): 235–253. doi:10.1007/s10612-015-9267-6. S2CID 144331678.

- Welch, Michael (2005). Ironies of Imprisonment. SAGE Publishing.

Further reading

- Seis, Mark; Nocella, Anthony J. II; Shantz, Jeff (2020). "Introduction: The Origins and Importance of Classic Anarchist Criminology". In Nocella, Anthony J. II; Seis, Mark; Shantz, Jeff (eds.). Classic Writings in Anarchist Criminology: A Historical Dismantling of Punishment and Domination. AK Press. pp. 5–17.

- Seis, Mark; Vysotsky, Stanislav (2021). "Anarchist Criminology: On the State Bias in Criminology". Journal of Extreme Anthropology. 5 (1): 143–159. doi:10.5617/jea.8949.

External links

- Criminology reading list, Anarchist Studies Network