| Anatomical Theatre of Padua | |

|---|---|

Teatro Anatomico di Padova | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Theatre |

| Architectural style | 16th century |

| Location | Palazzo del Bò |

| Address | Via VIII Febbraio, 2, 35122 Padova PD |

| Town or city | Padua |

| Country | Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°24′25.7″N 11°52′37.8″E / 45.407139°N 11.877167°E |

| Current tenants | Università degli Studi di Padova |

| Inaugurated | January 1595 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Stone and wood |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Paolo Sarpi and Dario Varotari |

The Anatomical Theatre of Padua, Northern Italy, is the first permanent anatomical theatre in the world.[1] Still preserved in the Palazzo del Bo,[2] it was inaugurated in 1595 by Girolamo Fabrici of Acquapendente, according to the project of Paolo Sarpi[3] and Dario Varotari.[4] This theatre constituted the model for the anatomical theatres built during the seventeenth century in the main universities of Europe: all would have been based on the Paduan archetype.[5] It is the symbol of a successful period in the University of Padua's history,[6] and it is considered one of the most important achievements for the study of anatomy during the sixteenth century.

Background history

The foundation: Padua and the tradition of dissections

"1222. Messer Giovanni Rusca of Como, podestà of Padua. In this period the studium of Bologna was transferred to Padua, and on Christmas Day after mass there was a great earthquake."[7]

This quote attests the foundation date traditionally accepted for the origins of the University of Padua.[8]

The events that led to the construction of the theatre could be dated back to the thirteenth century, when Pietro d'Abano performed the first autopsy recorded in Padua.

Pietro d'Abano (c.1250 – c.1315), was called to Padua from Paris as a teacher of medicine, philosophy and judicial astrology. His early studies in Constantinople allowed him to translate some of Galen's works from Greek to Latin: thanks to his work, the fame of the Studium spread rapidly throughout Italy.[9]

It is worth noting that in Padua a well-established practice of dissection had already existed since the late thirteenth century. In fact, a traditional legend hands down the story of an avaricious man's heart found in a basket by St. Anthony; the heart is described in a scientific way, showing how direct observation of the corpses was already considered essential.[10]

In the fifteenth century, the Padua Studium, like others, had three fundamental chairs of medicine: theoretical medicine, practical medicine, and surgery. Albeit the surgery teacher was expected to act as incisor in the anatomical demonstrations; only in the late sixteenth century was he formally charged with the teaching of anatomy.[11]

The first European public dissection

In 1404, during his stay in Vienna, Galeazzo di Santa Sofia undertook the first solemn public dissection, a practice he had obviously first seen and carried out in Padua.

Moritz Roth, the great Vesalius scholar, observes:

"If we think that the first dissection undertaken in Vienna was carried out by a professor from Padua, we have the impression that in the fifteenth century Padua at least reached the level of Bologna, if not actually overtaking it."[12]

Alessandro Benedetti and his temporary theatre

The turning point would have happened thanks to the contribution of Alessandro Benedetti, an Italian anatomist: in 1514, Anatomice sive historia corporis humani, the main of his works, was reprinted in Paris. This allowed the spread of his directives for the construction and the organization of a temporary wooden anatomical theatre, which Benedetti himself used and supported. According to him, anatomy should have been able to make medicine a more evincible science. In fact, direct observation was becoming even more important than theoretical studies.[13]

From Vesalius to the Anatomical theatre

In this stimulating atmosphere Andreas Vesalius, a Flemish anatomist, came to Padua (1537–1538) and wrote De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, in which he introduced the demonstrative method to medicine. This implied an active involvement in studying anatomy, now based on the direct observation and verification of theories: henceforward, it became a habit for students not only to read books, but also to approach the subjects physically.[14]

Since the late 1530s, when Vesalius became chair of surgery, dissections were carried out on corpses of dead criminals, but also on monkeys and dogs, in a temporary wooden anatomical theatre.[15] Moreover, Vesalius published his first Tabulae anatomicae, drawn together with a scholar of Titian. In this way, the De humani corporis fabrica, already mentioned, became a real piece of art, in which text was enriched with detailed depictions of dissected bodies.[16] According to the ancient tradition just described, it seems almost natural that the first permanent anatomical theatre was built in Padua.

It is also important to point out that its construction is linked to Fabrici d'Acquapendente, an Italian physiologist, who held the chair of surgery and anatomy in the Padua Studium for fifty years. Fabricius, in continuity with his predecessors, such as Benedetti and Vesalius, strongly supported the practical approach to anatomy as a means of effectiveness in the study of the subject.[5]

Architecture and main renovations

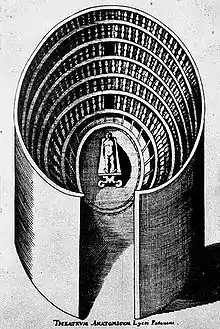

The architecture of the theatre is reminiscent of a funnel: it is an inverted cone inserted in a cylinder, arranged in steps to welcome the students.[17]

In 1739, Charles de Brosses observed that the theatre

"was built as a well, where up to five hundred students could sit to attend the lesson."

This idea of a well, probably too tight, was taken again in 1827, when in different archival documents it was suggested that lessons for medical and surgical students should have been separated.[18]

Nineteenth century

Originally, the theatre was built on two overlapping floors; the entrance was on the first floor, which was an open gallery. In 1822, the first intervention involved the building of a new room and the endowment of new equipment.[19] In the same period, renovations concerned also the construction of a different roof with a five-meter skylight in order to adapt the room to daylight. Previously the theatre was not illuminated by the eight windows on the walls because of the numerous flights of stairs that obscured the sunlight.

Furthermore, in 1841 the president of university required an improvement in the storage of corpses: within a year, the area was transformed into a wooden terrace, used to store bones. In the following years, professor Francesco Cortese noted small changes, such as floor rise, whitening of the railings and installation of a new desk, provided with a simple raising mechanism.[20]

In 1845, fundamental details in need of repair remained: they essentially related to the ventilation, a problem clearly linked to the presence of corpses, the smell of which made the air unbreathable. Speaking of this, the university president also wrote regarding the temperature situation: "sunbeams heat the theatre, so as to make it impossible to stay". Due to wind, "the roof let the rain fall abundantly".[21] February 13, 1848, was the official date of the end of the works.

In 1872, the theatre lost its function because the medical school was transferred to St. Mattia's former convent. In this situation, the theatre changed also part of its aspect: for example, the roof was demolished for security reasons and rebuilt without the skylight, which now is no longer useful for lessons.[22]

Twentieth century

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, issues regarding the potential reorganization of the theatre were very much present in academic debate. Different projects were proposed, but the current arrangement was undertaken by the architect Fagiuoli and the engineer Ronca. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that the architect Giò Ponti was responsible for redesigning the interior, thus giving the building its present appearance.[23]

Finally, it is worth noting that the theatre has kept its original funnel shape, with reference to its original function.

Value and symbolism

It is known that dissections were carried out by professors in their private homes or those of their students until the eighteenth century, even after the introduction of anatomical theatres. This shows that the increase in students more than the necessity of cutting-edge equipment led to the construction of the theatre.[24]

Anatomy lessons were a matter of pride for the university. The possibility to observe and experience a real dissection made the students elated. They could not take notes but only learn by watching. The typical funnel shape had the function of providing practical experience as a means to learn about the human body. It seems that its shape projects the students' gaze towards the deepest aspects of human anatomy.[25] Moreover, it is interesting that in the theatre those who held the chair were below the students, working near them, and not on a desk looming over them.[26]

Furthermore, anatomy lessons were the only form of practice lessons in the study of medicine, and the theatre made them look like a real ceremony.[27] The theatre is also linked to the number seven. Its rings, seven in number, can be connected to the seven skies of Empireum, or the seven pits of Hell in Dante's Divine Comedy.[28]

Notes

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 21.

- ↑ "The Anatomical Theatre at the University of Padua". venetoinside.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ↑ Rippa Bonati 1988–90, pp. 145–168.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 77.

- 1 2 Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, p. 169.

- ↑ "Teatro Anatomico". Università degli Studi di Padova. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Arnaldi 1977.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, p. 154.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, pp. 156–158.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Del Negro & Ongaro 2003, pp. 164–168.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 43.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 85.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 87.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 92.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 94.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 97.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 119.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, p. 121.

- ↑ Semenzato, Dal Piaz & Rippa Bonati 1994, pp. 123–124.

References

- Arnaldi, Girolamo (1977). Le origini dello Studio di Padova. Vol. 15. Padua: Il Mulino. pp. 388–431.

- Del Negro, Piero; Ongaro, Giuseppe (2003). The University of Padua, Eight Centuries of History. Padua: Signum Padova Editrice. pp. 11–12, 153–193.

- Rippa Bonati, Maurizio (1988). Le Tradizioni Relative Al Teatro Anatomico Dell'Università Di Padova. Vol. 35–36. Padua: Istituto di storia della medicina dell'Università di Padova. pp. 145–168.

- Semenzato, Camillo; Dal Piaz, Vittorio; Rippa Bonati, Maurizio (1994). Il teatro anatomico, Storia e Restauri. Padua: Offset Invicta Limena (PD) per Università degli Studi di Padova.

- "Teatro Anatomico". Università degli Studi di Padova. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "The Anatomical Theatre at the University of Padua". www.venetoinside.com. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

External links

- Anatomical Theatre of Padua su Himetop, The History of Medicine Topographical Database, at himetop.wikidot.com