| Andriivskyi Descent | |

|---|---|

Андріївський узвіз (Andriyivs′kyi uzviz) | |

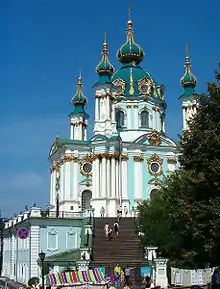

General view of Andrew's Descent with the Saint Andrew's Church in the background. | |

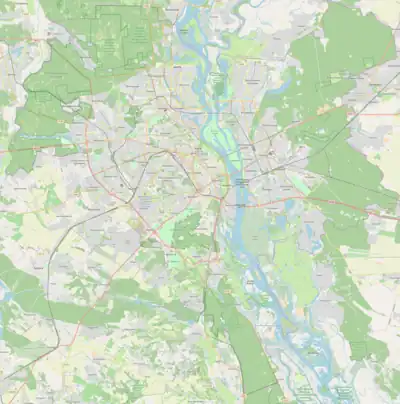

Location within Kyiv | |

| General information | |

| Type | National Landmark of Urban Planning[lower-alpha 1] |

| Location | Podil, Old Kyiv |

| Town or city | Kyiv |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Coordinates | 50°27′36″N 30°30′59″E / 50.46000°N 30.51639°E |

Andriivskyi Descent or Andrew's Descent[1][2][3][4] (Ukrainian: Андріївський узвіз, Andriivs′kyi uzviz) is a historic descent connecting Kyiv's Upper Town neighborhood and the historically commercial Podil neighborhood. The street, often advertised by tour guides and operators as the "Montmartre of Kyiv", is a major tourist attraction of the city.[5][6] It is included in the list of national landmarks by the government resolution.[7][lower-alpha 2] In addition, the street is also part of the Kyiv city historic reserve "Ancient Kyiv", while the St.Andrew's Church belongs to the National historic reserve "Sophia of Kyiv".

The descent, 720 metres (2,360 ft) in length, is constructed of laid cobblestones and connects Old Kyiv (Upper city) with Podil (Lower city). It starts at the end of Volodymyrska Street and winds down steeply around the Zamkova Hora hill, ending near the Kontraktova Square. Andrew's Descent is marked by some historic landmarks, including the Castle of Richard the Lionheart, the 18th century baroque Saint Andrew's Church, famed Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov's house, and numerous other monuments.

Recent talk of the descent's reconstruction has been going since 2006, when a local grassroots organization aimed at saving Andrew's Descent collected more than 1,000 signatures to petition local authorities to take action on the descent's reconstruction. On June 23, 2009, the Kyiv City Council administration approved the reconstruction of Andrew's Descent,[9] which was officially announced a year earlier by Mayor Leonid Chernovetsky. The exact timeline for reconstruction has not yet been adopted, although the reconstruction's budget has been drafted in the city's 2010 budget.[9]

Description

Andrew's Descent begins on the summit of the Starokyivska Hora (Old Kyiv mountain) near the ornate late-baroque Saint Andrew's Church (which gave the street its current name). The street continues on down and descends to the Podil district where it ends at the Kontraktova Square. In the past times, the descent was known as the Borychiv Descent mentioned as "Borichev uvoz" (Old East Slavic: Боричев увоз) by Nestor the Chronicler in his Primary Chronicle and in the 12th century poem, The Tale of Igor's Campaign (Slovo o polku Ihorevim).[10] The descent's current name is derived from the 18th century, at the time when the Saint Andrew's Church was erected atop the hill.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the street was mainly inhabited by merchants and craftspeople.[6] Although they are long gone due to the sweeping demographic changes[11] in Kyiv during times of the late Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, the street is once again thriving thanks to its unique topology, architecture, rich history and also many gift shops and small art galleries showcasing various paintings and sculptures by Ukrainian artists. The descent is one of the favorite spots for tourists.[6] It is also notable for the many festivals it holds, including various art festivals[6] and the Kyiv Day celebrations on the last weekend of May.[12]

The street's location in the city and its landmark attraction has made it lately a highly prestigious area, with several new luxurious restaurants. However, the descent's sewer and water systems have not been upgraded within the past 100 years, thereby underlining the need for a new system to be installed.[13] Although, city authorities have not yet scheduled a new sewer project system to be installed.[13]

History

.jpg.webp)

The descent, located between two hills, is the shortest passageway from the historic Old or Upper Town (Ukrainian: Князівська Гора; Kniazivs’ka Hora) to the commercial Podil neighborhood.[12] One of the hills, known as Uzdyhal’nytsia, was the place where pre-Christian idols once stood (see: Baptism of Kyiv), and another hill, called Zamkova Hora, served as a castle hill during the Middle Ages. For many centuries, this passageway was very steep and inconvenient, that's the reason why there were not any settlements for a long time. The first buildings were erected here only in the 17th century, and the first apartment buildings began appearing towards the end of the 19th century.

In 1711, by the order of then-Governor of Kyiv, the route between the Zamkova and Andriivskyi mountains were expanded, thus allowing traffic to become more suitable for horses and wagon carriages. Andrew's Descent was renamed in 1920 in honor of young revolutionary Georgiy Liver. In 1944, it was decided to return the street to its prior name; in 1957, the street was renamed back to Andreevsky Spusk—the Russian variant of Andrew's Descent.[14] In the 1980s, Andrew's Descent received a thorough reconstruction after years of disrepair.[15]

On April 9, 2012, construction workers began demolishing legally protected historic structures, even though earlier that year, their safety was guaranteed at several news conferences and the buildings themselves were included in scale models of the "renovated" descent. The destruction of the buildings took place under the guise of "reconstruction" efforts, which began in October 2011. Preliminary reports indicate that the buildings directly across from, and next to the Museum of Bulgakov, (Buildings 10a, 10b, and 9/11) were all razed to the ground. The land was being redeveloped to make room for a new office and business complex to house Rinat Akhmetov's Kyiv operations.[16][17]

Several hundred protestors, including boxer/politician Vitali Klitschko, gathered outside the main Kyiv office of Akhmetov's SCM Holdings.[18] On April 12, Akhmetov claimed he had canceled plans to build a multi-story business center in the buildings’ place, promising instead to build a cultural center and restore the facades.[18]

Attractions

Andrew's Descent contains numerous historic attractions and museums. The 18th century baroque Saint Andrew's Church; the late 19th century Mikhail Bulgakov's house-museum; the 20th century Castle of Richard the Lionheart; the Museum of One Street, chronicling the history of Andrew's Descent; and numerous other monuments attract tourists and Kyiv residents alike to the area.

Saint Andrew's Church

Another attraction of Andrew's Descent is the baroque Saint Andrew's Church. It is located atop a hill overlooking the Podil neighborhood from Andrew's Descent. The idea to construct the Saint Andrew's Church came from the Russian Tsaress Elizabeth Petrovna. When she visited Kyiv in 1747–1754, she laid the foundation brick of the church with her own hand, after which the church was constructed, to a design by the imperial architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli.[15]

As the Tsaress planned to take personal care of the church, the church has no parish, and there is no belltower to call the congregation to divine service. But she died before the construction ended, so the church was never cared for by Elizabeth Petrovna. After Elizabeth's death, the Kyiv court took no interest maintaining in the church, last consecrated in 1767. Later, there were not enough funds to maintain the church, which left the maintaining of the church to private and voluntary funds, such as Andrey Muraviov.[15]

In 1963, Rastrelli's original plans for the building were found in Vienna, Austria.[15] This made it possible to reconstruct the original images on the building. The plan of restoration was carried out in the 1970s, overlooked by the main architect-restorer, V. Korneyeva.[19] Since 1968, the church has been opened as a museum to tourists and visitors. The church is now owned by the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.[20]

Castle of Richard the Lionheart

The "Castle of Richard the Lionheart" house was built from 1902 to 1904. It was originally supposed to be called Orlov House in reference to its constructor Dmitry Orlov. But because its owner failed to clear the house construction with the city's authorities, a major scandal arose.[15] Viktor Nekrasov named the building "The Castle of Richard the Lionheart", after the 12th century English king in his book. It has been established that the modernized Gothic fronts were practically copied from a published design for a Saint Petersburg building by the architect R. Marfeld. But the stunning relief of Andrew's Descent softened the effect of this plagiarism.[15]

The cellar of the building contained a barber's shop, a grocery store and a butcher shop. The remaining premises were used as apartments for rent. When Dimitri Orlov died in 1911 while building a railroad in the Russian Far East, his widow, left with five children, had to sell off the house to pay her family's debts.[21] In 1983, renovation works were started on the building to convert it into a hotel.[21] Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, various reconstruction works have been largely unsuccessful. As of 2009, the Castle of Richard the Lionheart still stands empty and fenced off in renovation.[21]

Mikhail Bulgakov's house

Mikhail Bulgakov, a famous Kyiv-born Russian writer, and his family lived on the street at two different houses in the early-20th century. In Bulgakov's novel The White Guard the author vividly describes the street and house[15] (he calls it Aleksey Descent - "Alekseevskiy Spusk") in the turbulent times of the 1917 Russian Revolution. The address, at No. 13 Andrew's Descent is still commonly called the Bulgakov House and displays a plaque with the address the writer used in his book (No.13 Alekseevsky Spusk) (see image). Popular writer's statue is also installed near museum.

A museum was opened inside the preserved building to mark the 100th birthday of Mikhail Bulgakov on May 15, 1991.[15] The upper floor of the museum houses an exhibition of various Bulgakov objects, and the lower floor contains thematic exhibitions.[15] The house, built in 1888 and designed by architect N. Gardenin, was thoroughly renovated before the opening of the museum.[15] A memorial plaque with Bulgakov's portrait is now hanging on the front of the building.[15]

One Street Museum

The One Street Museum is another main attraction of Andrew's Descent, which houses many of the historic items of the descent, containing more than 6,500 exhibits. They include information about the Saint Andrew's Church, the castle of Richard Lionheart, and the many other buildings of the Descent.[22]

Also, the museum has a unique collection of various works by Ukrainian philologist P. Zhitetsky, Arabist and professor of the Kyiv University T. Kezma, journalist and public figure A.Savenko, Ukrainian writer G.Tyutyunnyk, which have lived in the house No. 34 in the different periods of the twentieth century.[22] Another important part of the collection in the museum is the memorabilia of professors of Kyiv Theological Academy A. Bulgakov, S. Golubev, P. Kudryavtsev, F. Titov, A.Glagolev, famed doctors Th. Janovsky and D. Popov, and other prominent local figures.[22]

The museum also has a large collection of antique books. Book relics of the exposition include a famous Trebnik of the Metropolitan of Kyiv Petro Mohyla, rare editions of works written by professors and graduates of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, unique books written by the Ukrainian Walter Scott, M.Grabovsky, the Defender of Orthodoxy, A.Muravyov, and the works of Mikhail Bulgakov published in his lifetime.

Lithuanian castle

The castle was built by Vladimir Olgerdovich, a progenitor of the Olelkovich family, in 1362. After being partially destroyed in 1648, in 1658 it was rebuilt as the Old Kyiv Fortress by the Russian city garrison.

Monuments

Andrew's Descent also has a number of monuments. One of them is the monument to Yaroslav the Wise, the Grand Prince of Novgorod and Kyiv, which depicts him holding a model of the Saint Sophia Cathedral. Another is the monument to Pronya Prokopovna and Svirid Golohvastov, which was unveiled in 1989, depicting two characters, Pronya Prokopovna and Svirid Golohvastov, from the play Chasing Two Rabbits, which was written by Mykhailo Starytskyi.[23] Another main monument on the street is dedicated to the famous Ukrainian poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, located to the right of the monument to Yaroslav the Wise.[24] The Shevchenko monument is the first monument to Shevchenko in Ukraine and was originally unveiled in Romny on 27 October 1918.[25]

Most recently, in 2007, a monument to Mikhail Bulgakov was opened on Andrew's Descent, the first dedicated to the writer in the former Soviet Union.[26]

Legends

During its long history, Andrew's Descent has a couple of legends surround it.

One legend states that when Andrew the Apostle visited the uninhabited mountains in the mid-stream of the Dnieper River (today's Andrew's Descent area), he put up a cross atop of the hill where the descent starts and prophesied a foundation of a great Christian city. Since that time, wooden churches sprang up around in the vicinity, completing his prophecy.[5]

According to another legend, there was once a sea where the Dnieper River now flows. When Saint Andrew came to Kyiv and erected a cross on the place where the Saint Andrew's Church now stands, the sea went away. The only part that remained of the sea is under the mountain on which Kyiv sits today. When the church was built there in the 18th century, a spring opened under the altar. The church has no bells, because, according to the legend, when the first bell strikes, the water can revive again and flood the left bank of Kyiv.[5]

Panorama

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ along with Zamkova Hora

- ↑ In 2012 the order of Ministry of Culture granted it a status of local landmark,[8] however in the latest published listing for local landmarks in the city of Kyiv for 26 July 2016, the descent is not on the list. (The listing is available at the Ministry of Culture's website.)

- Footnotes

- ↑ Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian (2016). Kyiv, Ukraine. The City of Domes and Demons from the Collapse of Socialism to the Mass Uprising of 2013–2014. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 179.

- ↑ Crankshaw, Edward (1956). Russia without Stalin: The Emerging Pattern. London: Joseph. p. 207.

- ↑ Johnstone, Sarah (2005). Ukraine. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. p. 55.

- ↑ Hardaway, Ashley (2011). Ukraine. Other Places Publishing. p. 78.

- 1 2 3 "Andreyevskiy Spusk". Hotels-Kiev.com. Optima Tours. Retrieved June 20, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 "Andreevsky Spusk" (in Russian). Kiev.inf. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ About entering national objects of cultural heritage to the State Registry of Immobile Landmarks of Ukraine (Про занесення об'єктів культурної спадщини національного значення до Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України). Resolution of Government of Ukraine No.928. 3 September 2009

- ↑ About entering objects of cultural heritage to the State Registry of Immobile Landmarks of Ukraine (Про занесення об'єктів культурної спадщини до Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України). Order of Ministry of Culture No.45. 20 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Andreevsky spusk in Kyiv will be reconstructed" (in Russian). Korrespondent.net. June 23, 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ Kudrytskyi 1981, p. 70.

- ↑ "A walk along the Andreevsky Spusk". Vash Kiev (Вашъ Кіевъ) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- 1 2 "Andriivskyi uzviz". Kyiv History Site. oldkyiv.org.ua. Archived from the original on 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- 1 2 "Historical architecture of the famous Andreevsky spusk will soon slide down to the Podol if famed 100-year-old sewer systems are not changed, reports ICTV" (in Russian). nashkiev.ua. December 24, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ "Monuments of history" (in Russian). Mandria. Archived from the original on 2010-12-22. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Malikenaite 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ "Three historic buildings were destroyed on Andrew's Descent. With the help of Akhmetov? PHOTO. VIDEO". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). April 10, 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Photos from the "hot spot" on the Andriivskyi Descent". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). April 10, 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- 1 2 Demolition on Andriyivsky Uzviz brings criticism, rethink by billionaire Akhmetov, Kyiv Post (12 April 2012)

(in Ukrainian) В Ахметова киянам сказали: Вибачте, ми двічі неправі, UNIAN (12 April 2012)

(in Ukrainian) Ахметов:сталася помилка, ми все виправимо, UNIAN (12 April 2012) - ↑ "St. Andrew's Church". travel.kyiv.org/Ukrainian/Russian. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ Makovets, Elena (May 28, 2008). "They are taking Saint Andrew's Church away from us". Gazeta po-Kievsky (in Russian). Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- 1 2 3 Sergey (February 6, 2009). "Kiev: Castle of Richard the Lionheart" (in Russian). kraevid.org. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "About museum". One Street Museum (in Russian). Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Pronya Prokopovna and Golohvastov". Unofficial site of Kyiv Oblast (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ Siyak, Ivan. Самые нелепые памятники Киева [The most absurd monuments of Kyiv] (in Russian). Nash Kyiv. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) 100 years ago the first monument to Taras Shevchenko was built for the Hetmanate, Radio Svoboda (14 October 2018)

- ↑ "In Kyiv the monument to Bulgakov was opened (FOTO)". ForUm (in Russian). October 20, 2007. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- Further reading

- Kudrytskyi, A. (1981), Kyiv, Encyclopedic Directory (in Ukrainian), Kyiv: Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia

- Malikenaite, Ruta (2003), Touring Kyiv (in Ukrainian), Baltija Dryk, ISBN 966-96041-3-3

External links

- "Andriivskyi uzviz". www.uzviz.com.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- "Andriivskyi uzviz". WWW Encyclopedia Kyiv (in Ukrainian).

- "Andriivskyi uzviz / Streets and squares of Kyiv / Attratctions of Kyiv / Old City". Interesniy Kyiv (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2009-03-29.

- "Andreevsky, which doesn't exist anymore". Museum Zamkova Hora (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2007-03-12.