Antonio Rojas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | El Matacuras |

| Born | May 10, 1818 Tepatitlán, Jalisco, New Spain, Spain |

| Died | January 28, 1865 (aged 46) Mascota, Jalisco, Mexico |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1858 – 1865 |

| Battles/wars | Reform War Second French intervention in Mexico † |

Antonio Rojas, nicknamed El Matacuras, was a Mexican Guerrilla who participated in the Reform War and the Second French intervention in Mexico. He fought independently in both wars due to his differing and controversial strategies and tactics throughout both wars until being killed at Mascota, Jalisco.

Reform War

He was born on May 10, 1818, at the ranch of El Buey within the vicinity of Tepatitlán.[1] On 1858, after capturing Guadalajara, an armed group under the command of Rojas killed the conservative general José María Blancarte, who was pardoned by the liberal forces. This caused Santos Degollado to issue a decree ordering for Rojas' capture although months later this sanction was erected by Degollado himself and pardoned Antonio Rojas from any punishment.[2]

On September 7, 1859, after the victory over Manuel Lozada's troops, General Esteban Coronado and his brigade entered Tepic and later Antonio Rojas arrived. A month later, the French vice-consul Frédéric Ricke and the British consul John Francis Allsopp sent a ship with a cargo of silver to a port not authorized by the republicans, and for this Rojas was sent to collect a fine. Faced with the arrest and some diplomatic complications, Rojas was accused of injuring Ricke and that, as a result, the French vice-consul died. However, Rojas insisted that he followed General Coronado's orders. In 1861, President Benito Juárez and his cabinet negotiated the delivery of more than 30,000 pesos as compensation for damages.[3]

In 1860 he captured the town of San Juan de Teúl in Zacatecas, shot 300 conservatives and ordered their wives and daughters to be distributed among his troops. He also collaborated in the capture of Fresnillo and Colima.[4] In the first months of that year he defeated the conservative generals Jesús Malo and Jerónimo Calatayud. However, due to his repeated looting and murder of civilians, he was a deeply unpopular figure among the liberal ranks with other leaders frowning upon him.[5]

Second French intervention in Mexico

When the French invaded Jalisco at the beginning of 1864, Rojas refused to put himself under the orders of José López Uraga, considering him a traitor and neither with José María Arteaga as considered him inept so he remained independently for months, being one of the few chiefs who prevented the French from dominating Jalisco with impunity. Together with Julio García, Antonio Rojas signed the Plan of Zacate Grullo, named after the hacienda in Jalisco where it was enacted and which sought to force the populations to define themselves politically regarding the war using terror. This agreement established the following:

- 1.- The men who are taken for the service of arms, will not be released for any reason, unless those recruited have some capital because, in this case, weapons and nothing else may be required of them.

- 2.- The assets of the force will be covered with the interests of the Mexican capitalists, taking first what belongs to the traitors, then what belongs to people who live in places occupied by the enemy and, in the last case, the interests of those who live among us.

- 3.- In order to carry out our movements more safely and to avoid a surprise, some of the towns, haciendas and ranches that remain in the intermediate line between the places occupied by the republican forces and those of the enemy will be destroyed.

- 4.- The French who present themselves to our forces or who are apprehended with weapons in hand or without them, will be ordered to take up arms immediately.

- 5.- The traitors who are apprehended with arms in hand, from the sergeant class upwards, will also be put under arms, suffering the same penalty for those who have accepted public jobs given by the invaders and traitors.

- 6.- The seeds, cattle and horses that can be collected from the line to be destroyed and from some other points, as agreed, will be taken to the point where our force must be concentrated in a given case.

- 7.- Those who sign this pact, remain under the indispensable obligation to fulfill it in the part that touches them, in the understanding that whoever breaks it is for the same subject to suffer the arbitrary penalty that others resolve against him. that they had not committed a crime.

Rojas's campaigns in the west of the country helped to strengthen the Republican forces led by Benito Juárez and the towns in which he participated at was Autlán, Mascota, Guadalajara, Tepic and Manzanillo. He was close to the soldiers Pedro Ogazón, Epitacio Huerta, Esteban Coronado, Ignacio Vallarta and Julio García, and to the guerrillas Simón Gutiérrez, Herrera and Cairo, Rochín and Ignacia Riesch.

It is said that his troops were made up of 4,000 troops, nominally the Red Brigade and known as the Galeanos or the Hacheros. His main military enemies were Manuel Lozada and Leonardo Márquez.

After failing in his attempt to invade Colima with 5,000 men, he returned to Jalisco after suffering numerous desertions that nearly made his army fully wiped out.[6] On January 28, 1865, his troops were ambushed by the French forces commanded by Captain Alfred Berthelin at the Potrerillos ranch at Mascota, Jalisco and was killed while fighting Berthelin's forces.[7] According to legend, Berthelin later adopted Rojas' dog until Berthelin was captured and hanged at Colima from an ambush.[5]

In Retrospect

For a guerrilla as experienced as Rojas, the ambush in which he was killed could be because he didn't recover from a gunshot wound that caused severe pain in his leg, causing his military skills to diminish. There are versions that his death was caused by revenge since he had so many pending accounts that one of his previous victims was the one who warned the French of the most vulnerable moment in which they could attack him.

Irineo Paz, who was a contemporary of Rojas, wrote a novel about him,[8] said the following:

“The readers already know who Antonio Rojas was, and the inhabitants of Jalisco know it even more, in whose state there was perhaps not a town that did not have to resent the horrors of his presence. He was a ferocious guerrilla, almost a bandit, whom Lozada himself, the powerful Tigre de Álica , became afraid of, making him tremble in the very center of his crossroads and burrows. Rojas, however, unlike Lozada and some famous bandits of that time, had the virtue of patriotism.[9]

Recovery of Skull

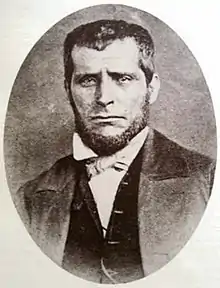

In 1887, the Smithsonian Institution received a donation of Rojas' skull by the French antiquarian Eugène Boban who was known for his ventures in skulls, notably in crystal skulls. When described about how he retrieved the skull, Boban stated that he acquired it from another collector who had bought it from a soldier. The skull was confirmed to be Rojas' when Dr. Jane Walsh compared the skull to a photograph of Rojas and the skull currently resides at the warehouses of the Smithsonian Institution.[5]

References

- ↑ Manuel Mestre Ghigliazza, Efemérides biográficas (defunciones-nacimientos), México, Antigua Librería Robredo, 1945, p. 89.

- ↑ Irineo Paz, Antonio Rojas. Leyendas históricas, segunda serie, leyenda primera, México, Imprenta, Litografía y Encuadernación de Irineo Paz, 1895, p. 56.

- ↑ Ilihutsy Monroy Casillas, “Un radical en el Occidente de México, El aparente secuestro de dos diplomáticos por Antonio Rojas, 1859-1861”, Revista del Seminario de Historia Mexicana, “Exclusión y violencia en México, Siglos XVIII al XX”, vol. IX, no. 1, primavera 2009, p. 9-17.

- ↑ “Antonio Rojas”, Liberales mexicanos del siglo XIX. Álbum fotográfico, México, Secretaría de Gobernación, 2000, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 Eric Taladoire (April 16, 2020). "El cráneo de Antonio Rojas". Sucesos de Veracruz (in Spanish). Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ↑ "Derrota de Rojas en Colima". El Diario del Imperio. January 13, 1865. p. 39.

- ↑ El Diario del Imperio, February 14, 1865, p. 151.

- ↑ Irineo Paz, Antonio Rojas. Leyendas históricas, segunda serie, leyenda primera, México, Imprenta, Litografía y Encuadernación de Irineo Paz, 1895.

- ↑ Irineo Paz, Algunas campañas, tomo I, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica-El Colegio Nacional, 1997, p. 59.

Bibliography

- Meyer, Jean, Esperando a Lozada, Guadalajara, Hexágono, 1989.

- Michel, Agistín y Jean Meyer, Mascota en la Gran Década Nacional, 1857-1867, México, Universidad de Guadalajara-CEMCA, 1994.

- Olveda, Jaime, Con el Jesús en la boca. Los bandidos de los Altos de Jalisco, Guadalajara, Universidad de Guadalajara, 2003.

- Peregrina, Angélica, “Antonio Rojas, un bandido jalisciense”, Boletín del Archivo Histórico de Jalisco, vol. II, núm. 2, mayo-agosto 1978.

- Segura Muñoz, Iván, “Las aventuras y desventuras de un guerrillero. Antonio Rojas y los Galeanos de Jalisco”, BiCentenario. El ayer y hoy de México, v. 12, n. 46, 2019, pp. 40–47.

- Vigil, José María, México á través de los siglos: historia general y completa del desenvolvimiento social, político, religioso, militar, artístico, científico y literario de México desde a antigüedad más remota hasta la época actual; obra, única en su género, tomo V, México, 1884.