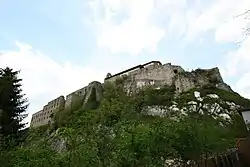

Arnoldstein Abbey (Stift Arnoldstein) was a Benedictine abbey in Arnoldstein in Carinthia, Austria. Its church was dedicated to St George and first mentioned in historical records in 1316 - its choir, tower, west door and a few buttresses can still be seen. The monastery buildings from the Gothic and 17th century eras were arranged around the church in an oval.

History

Origins

Arnoldstein is named after its founder Arnold, probably a ministerialis of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg but not evidenced elsewhere. He first built it between 1085 and 1090. The Bishopric had only been founded in 1007 and to mark his coronation on 10 February 1014 Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor had granted it various possessions in Carinthia, including in the area of what is now the market town of Arnoldstein.[1] Under the Bishop of Bamberg Adalbero of Eppenstein (1053-1057) the Eppsteiner family were the bishopric's vassals. However, they did not give the property back to Adalbert's successor but instead founded a castle in what is now Arnoldstein to fortify the 'Kanaltal' region. Only under bishop Otto of Bamberg soon after the turn of the century did the bishopric regain these lands.

To keep Arnoldstein in church hands, Otto founded a Benedictine monastery there in 1106. He had the castle demolished and converted into the monastery complex as well as leaving the abbey 155 'Huben' or farmsteads to finance its continued existence.[1] The abbey's first recorded abbot was Ingram, appointed in 1126 - prior to that it seems to have only been a priory. In 1126 its cemetery was opened. It also had early troubles with the governors - among others the lords of Ras misused their role as the abbey's protectors and so in 1176 it was made a direct bailiwick of the Carinthian dukes.

14th to 16th centuries

A poor harvest, a plague of locusts and finally a massive landslide on the Dobratsch caused by the 1348 Friuli earthquake led the abbey into economic problems - it lost buildings, its church and the village of St. Johann to the landslide. Documents show it began to recover until 1391, although the local population continued to decline, probably also due to the Black Death. In 1391 the Patriarch of Aquileia handed the abbey the parish of Hermagor to try to stem its financial problems, but this and further privileges, donations and foundations were not enough to pay off its debts. In the 15th century it even found it difficult to look after the parish of Hermagor and this led it into a dispute which involved the first witch trial in Carinthia, which occurred in the Grünburg Landgericht court in Hermagor in 1465.

Abbot Christoph allowed Jakob Fugger and his brothers to build a metal-separating works and a fortress on abbey lands in 1495, which became the foundation for the Fuggerau complex.[2] Abbot Friedrich complained in 1507 that the abbey had fallen into dilapidation and poverty and during the Reformation it was on the verge of dissolution, with its reputation weakened by the taxes on the princes to fund the war against the Ottoman Empire, its quarrels with nobles and subjects and its neglect of its pastoral duties. Despite the bishopric's edicts to the contrary, Lutheran preachers occupied the abbey and Thörl as well as the neighbouring fortresses. In 1570 abbot Petrus entered into a bond for 2500 guilders in installments to buy back the Fuggerau with all its lands and rights, since it had declined as a mining operation but still needed to be kept out of the hands of the neighbouring nobles, who might well go over to Protestantism at any moment.[3]

In 1580 the abbey was without an abbot for a short period - the Franconian Johannes Pünlein was appointed that year but according to the archpriest's visitation report in 1594 he led a completely secular life, only holding one mass a year with a single monk, maintaining an entourage that was entirely Protestant, using neither vestments nor candles in church and no adornments on the altar. His successor was another Franconian, Emerich Molitor, who could not fulfil the bishopric's hopes of re-catholicising the abbey. Embezzlement led to a loss of 60,000 guilders.

17th century to present

In a bull by Ferdinand II of Tyrol of 12 April 1600 the abbey was finally connected to a Jesuit college set up at St. Veit, but the bishop of Bamberg was finally able to avert this by instead promising a contribution to the college's costs. After the free election of abbot Daniel in 1630 the abbey began to flourish once again until a major fire in October 1642, in the wake of which its funds were invested in buildings and equipment.

When the Patriarchate of Aquileia was dissolved and Bamberg's lands sold off to Austria in 1759 the abbey came under the princes' direct control. IN 1782 Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor decided to abolish all monasteries in Austria that did not make a direct contribution to education or nursing. He originally wanted to save Saint Paul's Abbey, Lavanttal but his advisors convinced him that abolishing Arnoldstein Abbey would do less damage. A court decree thus abolished it on 24 November 1783, with abbot Otto von Größing and 18 priests there allowed to choose becoming parish clergy or to switch to another monastery. The abbey's buildings and lands were transferred to the state and its library was transferred to the Klagenfurter Studienbibliothek, now known as the library of the University of Klagenfurt. Part of the abbey archives went to the Geschichtsverein für Kärnten and is now in the Carinthian National Archives (Kärntner Landesarchiv) in Klagenfurt. The abbey's rooms were used as government offices, rented and even (until 1854) used to house elementary school teachers.

The 1848 administrative reforms turned them into offices for the forestry administration, the district courts, the tax offices, the land registry, the notaries and the town council. Another fire on 16 August 1883 destroyed the buildings' wooden roofs and ceilings but the administration was unwilling to raise funds to repair them and so they were left to fall into ruin. The grounds were acquired by the Revitalisierungsverein Klosterruine Arnoldstein association on 16 August 1883[4]

References

- 1 2 (in German) Kreuzer 1986, S. 71

- ↑ "Chronik des Blei- und Zinkbergbaues in Bezug zur Bleiberger Bergwerks Union" (in German). Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ Götz von Pölnitz (1951). Jakob Fugger, Band 2 (in German). p. 37. ISBN 9783168145721.

- ↑ (in German) Revitalisierungsverein Klosterruine Arnoldstein

Bibliography (in German)

- Wilhelm Deuer: Die Klosterruine Arnoldstein. Revitalisierungsverein Klosterruine Arnoldstein, Arnoldstein, 2006

- Gernot Rader: Villach Geschichten - Teil 2. Santicum Medien GmbH, 2010, Villach, S. 20 f.

- Wilhelm Deuer: Burgen und Schlösser in Kärnten. Verlag Johannes Heyn, Klagenfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-7084-0307-6, S. 207–209.

- Anton Kreuzer: Die Stifte und Klöster Kärntens. Carinthia Verlag, Klagenfurt 1986, ISBN 3-85378-242-6, S. 71–76.

- Klosterruine Arnoldstein

- Liste der Äbte bis 1688 (Valvasor): 1126–1544&1544–1688