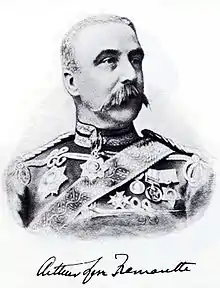

Sir Arthur Lyon Fremantle | |

|---|---|

Sir Arthur Lyon Fremantle | |

| Born | 11 November 1835 |

| Died | 25 September 1901 (aged 65) Cowes Castle, Isle of Wight, England |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1852–1901 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Mahdist War |

| Awards | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Companion of the Order of the Bath |

General Sir Arthur James Lyon Fremantle GCMG CB KStJ (11 November 1835 – 25 September 1901) was a British Army officer and a notable British witness to the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Whilst holding the rank of "Captain and Lieutenant Colonel" he spent three months (from 2 April until 16 July 1863) in North America, travelling through parts of the Confederate States of America and the Union. Contrary to popular belief, Colonel Fremantle was not an official representative of the United Kingdom; instead, he was something of a war tourist.

Early life and career

Fremantle was born into a distinguished military family; his father, Lieutenant-General John Fremantle, had commanded a battalion of the Coldstream Guards, and had served during the Peninsular War and Waterloo Campaign, as well as acting as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General John Whitelocke during the abortive British invasion of Buenos Aires in 1807. Arthur's middle name, Lyon, came from his mother, Agnes Lyon.[1] He was called "Arthur" after the Duke of Wellington, who had been the first witness at his parents' wedding in 1829.[2]

After his graduation from Royal Military College, Sandhurst, Arthur Fremantle was commissioned into the British Army in 1852,[3] serving firstly as an ensign in the 70th Foot, before being transferred to the 52nd Foot almost immediately thereafter. The following year, Fremantle became ensign and lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, and continued to receive promotions until, in 1860, at the age of 25, he held the rank of captain of his regiment and lieutenant colonel in the Army.[3]

The same year, Fremantle was appointed to the position of assistant military secretary at Gibraltar under Governor William Codrington. In January 1862, the Confederate commerce raider CSS Sumter, pursued by the Union Navy, arrived in port. The ship's commander, Raphael Semmes, sought to have his ship repaired and refitted, although ultimately the Sumter was sold and its crew transferred to the newly constructed CSS Alabama. Sometime in early 1862, the young British captain met the flamboyant Confederate captain, and was inspired by Semmes' tales of blockade running and combat on the high seas.[4]

Like many other officers of his generation, including Lieutenant Colonel Garnet Wolseley, Fremantle had a considerable interest in the American Civil War. Unlike most of the others, however, he decided to take a tour of the South, and applied for a leave of absence in 1863. By his own admission, his initial sympathies lay with the Union, due to his natural distaste for slavery. But as stated in his own book, in the Preface:

At the outbreak of the American war, in common with many of my countrymen, I felt very indifferent as to which side might win; but if I had any bias, my sympathies were rather in favour of the North, on account of the dislike which an Englishman naturally feels at the idea of Slavery. But soon a sentiment of great admiration for the gallantry and determination of the Southerners, together with the unhappy contrast afforded by the foolish bullying conduct of the Northerners, caused a complete revulsion in my feelings, and I was unable to repress a strong wish to go to America and see something of this wonderful struggle.[5]

On 2 March 1863, Captain and Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle left England on board the mail steamer Atrato.[6]

Travelling through Texas

Fremantle entered the Confederacy through the Mexican town of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on 2 April on board the Royal Navy frigate HMS Immortalité to avoid being in violation of the Union blockade, and crossed the Rio Grande into Brownsville, Texas.[7] Within three hours of his arrival in the Confederacy, Fremantle encountered 'frontier justice' for the first time, finding the body of a renegade, known as Montgomery, half-buried and stripped of flesh at the roadside.[7] Spending almost two weeks in Brownsville, with occasional visits across the border to Matamoros and the village of Bagdad,[7] Fremantle became acquainted with General Hamilton P. Bee and several merchants and diplomats who were facilitating the trade of cotton across the border with Mexico.[7] Part of the reasoning for Fremantle's tenure in Brownsville may have been that he wished to meet General John B. Magruder, for whom he had a letter of introduction.[8] However, Magruder was delayed, and Fremantle left Brownsville on 13 April in a carriage in the company of some of his merchant friends. Their driver and his assistant, Mr Sargeant and Judge Hyde, are particularly memorable figures from Fremantle's diary, in no small part due to Fremantle's astonishment that a member of the justiciary should be working on a stagecoach.[9] Later, General Longstreet would recall meeting the same two men during his own service in Texas.[10]

After finally meeting with General Magruder shortly after leaving Brownsville, Fremantle continued his journey across the South Texas prairie, dutifully recording in his diary his observations about the taste of polecat,[11] the snuff habits of Texan women,[11] and allusions to the coarse language of his drivers and travelling companions. He finally arrived in San Antonio, Texas, on 24 April, where he sold most of his luggage, and from there travelled to Houston, Texas, where he arrived on 30 April.[12] Here, he dined with General William Read Scurry, and observed that those Confederate officers he encountered were extremely complimentary about Great Britain and the Queen, even proposing toasts to her health and to the Empire.[13] Fremantle now proceeded with haste across the remaining Texan countryside, as rumours concerning the fate of Alexandria, Louisiana began to reach him.[14] Furthermore, the continuing siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, was another source of anxiety, as the capture of the city would make passage across the Mississippi River practically impossible.[15]

Setting off for Galveston, Texas, on 2 May, Fremantle found himself meeting Sam Houston, the father of Texan independence, though he found the elder statesman to be vain and egotistical, as well as bitter and uncouth in his mannerisms.[14] This occurred less than three months before Houston's death, presumably making Fremantle one of the last foreign visitors to meet the general. The English observer finally left Texas on 8 May, arriving in Shreveport, Louisiana, and partaking of the hospitality of General Edmund Kirby Smith and his wife.[16]

From Louisiana to Tennessee

On the advice of General Kirby Smith, Fremantle made his way to Monroe, Louisiana, to attempt to cross the river from there due to the uncertainty surrounding the status of Alexandria. By the morning of 10 May, the day Fremantle's stagecoach arrived at its destination, travellers began to report that the city had fallen. In Monroe itself, Fremantle learned of the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, although the news was accepted by locals without excitement.[17] The wounding of Stonewall Jackson, however, caused some distress.[17] The high expectations of Southerners, and their contempt for their enemies, would be among the few major points of criticism made by Fremantle. After considerable anxiety on board a steamer on the Mississippi, Fremantle finally crossed the river and arrived in Natchez, Mississippi, on 15 May.[18]

From Natchez, Fremantle travelled to Jackson, which he reached on 18 May. As the city had been evacuated and attacked only a few days earlier, Fremantle was treated with some suspicion by soldiers and locals, who expressed scepticism that an English officer should be travelling alone through the South. One local, the gun-toting Mr Smythe, even went so far as to threaten the foreign visitor with execution should he be unable to prove his identity and credentials. Upon 'examination' by a mob in a hotel, Fremantle finally convinced a Confederate cavalry officer and an Irish doctor of his legitimacy, and was spirited away to meet General Joseph E. Johnston, who accepted the peculiar traveller into his company. Fremantle remained near Johnston for several days, learning of the death of General Jackson from his Chancellorsville wound.[19]

Fremantle's next stop was at Mobile, Alabama, which he reached on 25 May after an eventful journey by train, in which a railway engineer shot a passenger.[20] After inspecting the defences of the city with General Dabney H. Maury, Fremantle briefly visited Montgomery, the former capital of the Confederate States, before arriving in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on 28 May.[21] Here, Fremantle met yet more prominent figures, including Generals William J. Hardee and Leonidas Polk, and Clement Vallandigham, the leader of the Copperheads.[22] Later, Fremantle also encountered Braxton Bragg, who supplied the Englishman with letters of introduction and passes, allowing him to travel to Shelbyville, which he reached the following day.[23] Fremantle remained here until 5 June, inspecting troops in the company of General Hardee, his fellow Englishman Colonel George St. Leger Grenfell and the Irish-born General Patrick Cleburne.[24] He also witnessed the baptism of General Bragg, and a small skirmish between Federal and Confederate forces outside the town, before leaving for Charleston the following day.[25]

On to Richmond

Increasingly, Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle became possessed of a desire to get to the Confederate capital, Richmond, and from there attempt to locate the Army of Northern Virginia, with which he intended to journey for a while. From Tennessee, he travelled through Augusta and Atlanta, before arriving in Charleston, South Carolina, the birthplace of the war, on 8 June. The English tourist was keen to inspect the defences of the city, and remained there until 15 June, inspecting Fort Sumter and visiting Morris Island in the company of General Roswell S. Ripley, commander of South Carolina's First Military District.[26] During this stay, Fremantle also met General PGT Beauregard, and a member of Captain Raphael Semmes' crew from the CSS Sumter, whom Fremantle had first met in Gibraltar in 1862.[27]

En route to Richmond, Fremantle passed through Wilmington, North Carolina, and Petersburg, Virginia, before arriving in the Confederate capital two days after leaving Charleston. On the day of his arrival, he was granted a meeting with Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin.[28] During the audience, Benjamin assured Fremantle that British diplomatic recognition of the C.S.A. would terminate the war without more bloodshed, though the British officer was concerned about a possible Union invasion of Canada. Benjamin also complained to his guest about revelations about his gambling habits made by the former correspondent of The Times, William Howard Russell. Benjamin then took Fremantle to see President Jefferson Davis, with whom he spoke for an hour. From Fremantle's account, it is possible to conclude that the Confederate leaders may have been trying to impress their British visitor on the matter of diplomatic intervention, without real consideration of his lack of power to do so.[29]

Intent on finding Lee's army at the earliest opportunity, Fremantle visited the Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon on 18 June, where he was furnished with letters of introduction to Generals Lee and Longstreet.[3] Leaving Richmond two days later, Fremantle came upon the division of General William Dorsey Pender on 21 June, and reached Lee's headquarters at Berryville a day later.[30]

Here, Fremantle met the individuals who would be his companions for the next two weeks. Among them were Francis Charles Lawley, the Times correspondent who had replaced Russell, Captain Fitzgerald Ross, an Austrian cavalry officer, and Captain Justus Scheibert, a Prussian army engineer who had been sent to inspect Confederate fortifications by his government.[30] The accounts of these four men present the most enlightening accounts written by foreigners of the Campaign and Battle of Gettysburg.[30]

Gettysburg

Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle introduced himself to General Longstreet on 27 June, a crucial meeting since it allowed Fremantle to observe the advance through Maryland and Pennsylvania in close quarters to the General and his staff. As well as the other foreign observers, Fremantle also became well acquainted with some of Longstreet's staff officers, including Gilbert Moxley Sorrel, Thomas Goree, and the medical staff, Doctors Cullen and Maury. As a neutral observer, Fremantle was allowed to enter the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, which was off-limits to most soldiers and officers on the orders of General Lee.[31]

On 30 June, Fremantle met the famous commander of the Army of Northern Virginia for the first time, and learned from Longstreet that General George Meade had replaced Joseph Hooker as commander of the Army of the Potomac. In the camp, Fremantle spoke to the staff officers about the likelihood of battle in the near future. The next day, the sound of artillery fire alerted the English visitor that the two armies had indeed met each other. According to Fremantle's diary, a spy, presumably Henry Thomas Harrison, informed the company that there was a significant concentration of Union troops around Gettysburg. Whilst talking to Union prisoners, Fremantle met General Ambrose Powell Hill, who complained of being ill.[32] Later in the evening, when the Union forces had reformed on Cemetery Ridge, Fremantle climbed a tree to observe the last of the fighting, before consulting with Longstreet again about the following day's action.[32]

On 2 July, the four foreign observers returned to the battlefield at 5 am, in time to witness a meeting between Generals Lee, Longstreet, Hill, John Bell Hood and Henry Heth. Once more, Fremantle climbed his tree to see what was happening, this time in the company of Captain Scheibert. After touring the Confederate lines, Fremantle returned to that position at about 2 pm on the advice of General Longstreet, but was frustrated that the attack did not take place until well after 4 pm. For the first time, the Englishman heard the 'Rebel Yell', as well as a Confederate band playing polkas and waltzes above the din of battle. That evening, news reached the observers of the wounding of General Hood, as well as the death of General William Barksdale.[33]

On the morning of 3 July, Captain Ross and Colonel Fremantle made an inspection of the town of Gettysburg itself, intending to get to the cupola of the seminary, which had been used by General John Buford as a vantage point two days earlier. The commencement of the Union bombardment stopped the two observers, and so they returned to Longstreet's headquarters early in the afternoon. Fremantle alone found the General sitting on a small fence. Thinking that the battle was just getting under way, Fremantle commented to Longstreet that he 'wouldn't have missed this for anything'. Longstreet wryly pointed out to his guest that the attack had already happened, and had been repulsed. Longstreet asked if Fremantle had anything to drink, at which the Englishman made a gift to the general of his silver hip flask.[34]

Coming upon Lee, Fremantle found him rallying the defeated troops, reassuring them and trying to rally them ahead of an anticipated Union counterattack. The Union counterattack did not come, however, and Fremantle retreated along with the rest of the Confederate Army on the night of 4 July. As the army fell back into Maryland, Fremantle met Jeb Stuart, the cavalry commander whose absence during the preceding battle cost Lee valuable intelligence. On 7 July, Fremantle took his leave of Longstreet and his staff, intending to cross the Union lines and make his way to New York City. A parting remark made by Major Latrobe did little to reassure him: 'You may take your oath he'll be caught for a spy'.[35] Longstreet was more confident of Fremantle's abilities, informing his aide that, since Fremantle had managed to travel across lawless areas of Texas, crossing the Union lines would cause him little difficulty.[35]

Two days later, in Hagerstown, Fremantle left Lawley and Ross, and made his way towards the Union Army.[36] Despite initial suspicion, Fremantle convinced General Benjamin Franklin Kelley that he was no spy, even showing the officer a pass from General Lee verifying Fremantle's neutral status.[37]

New York and the Draft Riots

His passage having been secured, Fremantle arrived by train in New York City on the night of 12 July, booking into the Fifth Avenue Hotel.[38]

The following day, Fremantle went out for a walk along Broadway. Upon his return to the hotel, he found that shopkeepers were closing their shutters early, and then noticed that several buildings were ablaze. Fire engines were present, but the crowd was not permitting them to be used. Increasingly alarmed, Fremantle saw a black youth pursued by the mob, eventually finding refuge with a company of soldiers, to the disgust of the massed protestors. Bewildered, the Englishman asked a bystander why the crowds were so vehement in their hatred of blacks. In response, he was told that they were 'the innocent cause of all these troubles'.[39]

In fact, the New York City draft riots (13–16 July 1863), the most violent insurrection in the history of the US had begun, and were eventually to evolve into an anti-black pogrom. A day later, Fremantle noted that the activities of the mob were worsening, with battles between police and rioters now taking place in the streets. An English captain reported that the mob had forced their way onto his ship and beaten his black crew members, forcing a French warship to threaten violence against any attacks against foreign vessels.[40]

Return to England

On 15 July, amidst the violence and terror gripping large parts of the city, Fremantle boarded the SS China, and began his voyage back to Britain.[41]

Upon returning to England, the young Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle found himself being questioned by friends and colleagues on the truth of the situation in the Confederate States, as only Union newspapers were readily available in England. Suitably encouraged, Fremantle wrote a book on his experiences in America, Three Months in the Southern States, based on the diary which he kept throughout his sojourn in the South. Published in 1864, the book was well-received both in Great Britain and in the Union, and it was even printed in Mobile by S.H. Goetzel & Co., being eagerly read even by the beleaguered Southerners, who wanted to see how their struggle was being reported by a foreign visitor.[42]

Later life and career

Fremantle married shortly after his return to Great Britain, and served with his regiment until 1880, when he was placed on half pay after 28 years of service without seeing any active duty. The following year, however, he was promoted to the rank of major general and assigned as aide-de-camp to Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, commander-in-chief of the British Army.[43]

The United Kingdom was upset by the disasters suffered by the Anglo-Egyptian forces contending with the Mahdist army in the Sudan (Battle of El Obeid; 1st Battle of El Teb). Fremantle was sent to the Sudan, temporarily serving as garrison commander at the port of Suakin.[43]

Fremantle followed General Graham in his inland raid when he intended to crush the Mahdist Osman Digna. Fremantle was in command of the Brigade of Guards and as such took part in the harsh Battle of Tamai.[44]

After the fall of Khartoum and the departure of the British from the Sudan, Fremantle stayed for a brief time in Cairo, then returned to England in 1886, serving in the War Office as Deputy Adjutant-General for Militia, Yeomanry and volunteers.[43] In February 1893 he became Commander-in-Chief, Scotland, a post he held for less than a year.[43]

He ended his career on a high note by being appointed to the office of Governor of Malta in January 1894.[43] During his time on the island, Fremantle became a popular governor, presiding over political decisions such as the matter of mixed and non-Catholic marriages, and the issue of the payment of reparations to the Maltese ecclesiastical authorities from the Napoleonic Wars. In 1897, Fremantle renamed the line of fortifications that was under construction the Victoria Lines to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. In November 1898, he hosted a visit to the island by the German Emperor, Kaiser William II, who arrived in Valletta on board his personal yacht, the Hohenzollern, upon which Governor Fremantle joined the Kaiser for dinner.[44]

In 1899, after his term in office ended, Lieutenant-General Arthur Fremantle returned to England.[43] Fremantle was appointed a Knight of Grace of the Order of St John on 7 March 1900.[45]

A member of the Royal Yacht Squadron, General Fremantle died at the age of 65 in the Squadron's headquarters in Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight from complications of asthma on 25 September 1901.[43] On the centenary of his funeral, a ceremony marking the restoration of his grave in Woodvale Cemetery, near Brighton, was conducted by his descendants and by Civil War re-enactors from the United States.[46]

Legacy

Although the book was a best-seller at the time, the ultimate defeat of the Confederacy led to a sharp decrease in Britain of the appetite for Civil War diaries after 1865, including Fremantle's diary. In 1952, however, historian Walter Lord published a revised edition of Three Months in the Southern States, retitled The Fremantle Diary, which featured an introduction by the editor and detailed references.[47]

In popular media

Part of the reason for the enduring fame of Fremantle compared to his fellow observers may be his role in Civil War literature and film, thanks to the success of Michael Shaara's historical novel, The Killer Angels. The novel, published in 1974, deals with the events of the Battle of Gettysburg and the effects of the engagement on some of the main protagonists, including Generals Longstreet and Lee, as well as Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and General John Buford. Shaara's primary source material for researching the novel included the diaries, letters and correspondence of figures who were either involved in or present at the Battle.[48]

In the 1993 film adaptation of Shaara's novel, retitled Gettysburg, Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle is portrayed by James Lancaster. His character changes little from the book, once again engaging in important discussions with General Longstreet and his officers on the Confederacy's relations with the United Kingdom.[49] However his appearance is substantially different from reality: in the movie he is shown in a scarlet British uniform sipping tea from a china cup, whereas, being in an unofficial capacity, he was dressed in a "gray shooting-jacket" and had been living rough like many others in the country.[50]

Since 1993, Fremantle has been portrayed in historical re-enactments in the United States by Roger Hughes, who also led the efforts to have Fremantle's grave in Brighton restored in 2001. Hughes maintains a website providing considerable information on Fremantle, his family, his travels and Civil War re-enactments.[51]

References

- ↑ Mosley, Charles, editor. Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes. Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003.

- ↑ Glover, Gareth; Fremantle, John (2012). Wellington's Voice: The Candid Letters of Lieutenant Colonel John Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, 1808–1821. Casemate Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-78337-867-8.

- 1 2 3 Hodges, Robert (6 December 2006). "An Englishman's Journey Through the Confederacy During America's Civil War". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Campbell (2003), p. 118.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 3.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Fremantle (1864), p. 6.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 7.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 17.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 27.

- 1 2 Fremantle (1864), p. 26.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 34.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 35.

- 1 2 Fremantle (1864), p. 40.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 42.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 43.

- 1 2 Fremantle (1864), p. 46.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 50.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 53.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 66.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 70.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 71.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 75.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 78.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 90.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 94.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 101.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 105.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 107.

- 1 2 3 Fremantle (1864), p. 115.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 121.

- 1 2 Fremantle (1864), p. 128.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 132.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 135.

- 1 2 Fremantle (1864), p. 144.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 146.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 147.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 150.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 151.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 152.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 155.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), pp. 1–158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sorrel (1959), pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Arnold, Zac. "Arthur Fremantle: The Coldstreamer Chronicler". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "No. 27172". The London Gazette. 9 March 1900. p. 1628.

- ↑ "Preservation News Update". American Civil War Round Table. 31 August 2001. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Fremantle (1954), pp. 1–304.

- ↑ Shaara (1987), pp. 1–345.

- ↑ "Gettysburg". IMDb. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Fremantle (1864), p. 207.

- ↑ "Roger Hughes". Smash Words. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

Sources

- Duncan, Andrew Campbell (2003). English Public Opinion and the American Civil War. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0861932634.

- Fremantle, Arthur (1864). Three Months in the Southern States: April, June, 1863. S. H. Goetzel.

- Fremantle, Arthur (1954). The Fremantle Diary: A Journal of the Confederacy (Walter Lord, ed.). Burford Books. ISBN 978-1580800853.

- Shaara, Michael (1987). The Killer Angels. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-44412-7.

- Sorrel, Gilbert Moxley (1959). Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer. McCowat-Mercer Press. ISBN 0803268750.

Further reading

- Longstreet, James, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America, J. B. Lippincott and Co., 1896, (reprinted by Da Capo Press) ISBN 0-306-80464-6.

- Lonn, Ella, Foreigners in the Confederacy, University of North Carolina Press, 1940, (reprinted 2002), ISBN 0-8078-5400-X.