The Atrebates (Gaulish: *Atrebatis, 'dwellers, land-owners, possessors of the soil') were a Belgic tribe of the Iron Age and the Roman period, originally dwelling in the Artois region.[1]

After the tribes of Gallia Belgica were defeated by Caesar in 57 BC, 4,000 Atrebates participated in the Battle of Alesia in 53, led by their chief Commius. They revolted again in 51 BC, after which they maintained a friendly relationship with Rome, as Commius received sovereignty over the neighbouring Morini.[1][2] The quality of their woollens is still mentioned in 301 AD by Diocletian's Price Edict.[2]

An offshoot of the Belgic tribe probably entered Britain before 54 BC, where it was successively ruled by kings Commius, Tincommius, Eppillus and Verica. After 43 AD, only parts of the area were still controlled by king Claudius Cogidubnus, after which they fell under Roman power.[3]

Name

They are mentioned as Atrebates by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[4] Atrebátioi (Ἀτρεβάτιοι) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD),[5] Atribátioi (Ἀτριβάτιοι) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[6] Atrébas (Ἀτρέβας) by Cassius Dio (3rd c. AD),[7] and as Atrabatis in the Notitia Dignitatum (5th c. AD).[8][9]

The ethnonym Atrebates is a latinized form of the Gaulish *Atrebatis (sing. Atrebas), which literally means 'dwellers, land-owners, possessors of the soil'. It derives from the Proto-Celtic stem *attreb- ('settlement') attached to the suffix -atis ('belonging to'), the former descending, as a result of an assimilation from an earlier *ad-treb-, from the Proto-Indo-European root for 'settlement', *treb- (cf. Osc. trííbúm, Germ. *Þurpa, Lith. trobà 'house'). The ethnic name is cognate with the Old Irish ad-treba ('he dwells, cultivates') and attrab ('possession, the act of occupying, a dwelling'), the Modern Irish áitreabhach ('inhabitant'), and the Middle Welsh athref ('dwelling-place, abode').[10]

The city of Arras, attested ca. 400 AD as civitas Atrabatum ('civitas of the Atrebates'; Atrebatis in 881, Arras in 1137), the region of Artois, attested in 799 as pago Atratinse ('pagus of the Abrates'; Atrebatense castrum in 899, later Arteis), and the Arrouaise Forest, attested ca. 1050 as Atravasia silva ('forest of the Atrebates'; Arwasia in 1202), are all named after the Belgic tribe.[11]

Geography

Territory

The Belgic Atrebates dwelled in the present-day region of Artois, in the catchment area of the Scarpe river.[12][1] They commanded two hill forts: a large and central one near Arras, and a frontier one on the Escaut river.[12] The Atrebates were separated from the Ambiani by the Canche river.[12]

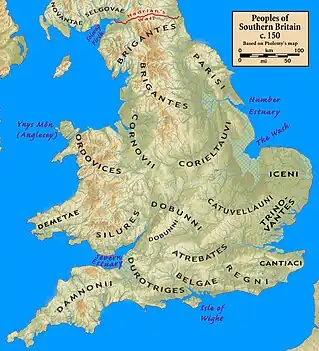

In the mid-first century BC, an offshoot of the tribe lived in Britain, where they occupied a region stretching between the Thames, the Test, and West Sussex.[3]

Settlements

During the Roman period, their centre was transferred from the hill-fort of Etrun to Nemetocennae (present-day Arras), on an important road junction.[2] The name Nemetocennae means in Gaulish either 'far' or 'born' 'from the sacred wood, the sanctuary', stemming from the root nemet(o)- ('sacred wood' > 'sanctuary') attached to the suffix -cenna ('far') or, more likely, to a deformed suffix -genna ('born from').[13] It is later attested as Metacon by Ptolemy (ca. 170 AD), and as Nemetacum (ca. 300 AD) or Nemetaco (365), with the same root attached to the Gaulish suffix -acos.[13]

Before 54 BC, an offshoot of the Gallic tribe probably settled in Britain.[3] After the Roman invasion of Britain, three civitates were created in the late 1st c. BC: one of the Atrebates, with a capital in Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester); one of the Belgae with its capital at Venta Belgarum (Winchester); and one of the Reg(i)ni, with a capital at Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester).[3]

History

Gaul

In 57 BC, they were part of a Belgic military alliance in response to Julius Caesar's conquests elsewhere in Gaul, contributing 15,000 men.[14] Caesar took this build-up as a threat and marched against it, but the Belgae had the advantage of position and the result was a stand-off. When no battle was forthcoming, the Belgic alliance broke up, determining to gather to defend whichever tribe Caesar attacked. Caesar subsequently marched against several tribes and achieved their submission.

The Atrebates then joined with the Nervii and Viromandui and attacked Caesar at the battle of the Sabis, but were there defeated. After thus conquering the Atrebates, Caesar appointed one of their countrymen, Commius, as their king. Commius was involved in Caesar's two expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BC and negotiated the surrender of Cassivellaunus. In return for his loyalty, he was also given authority over the Morini. However, he later turned against the Romans and joined in the revolt led by Vercingetorix in 52 BC. After Vercingetorix's defeat at the Siege of Alesia, Commius had further confrontations with the Romans, negotiated a truce with Mark Antony, and ended up fleeing to Britain with a group of followers. However, he appears to have retained some influence in Gaul: coins of post-conquest date have been found stamped with his name, paired with either Garmanos or Carsicios, who may have been his sons or regents.

Britain

| Atrebates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography | |

| Capital | Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) |

| Location | Hampshire West Sussex Berkshire |

| Rulers | Commius Tincomarus, Eppillus, Verica |

Commius soon established himself as king of the British Atrebates, a kingdom he may have founded. Their territory comprised modern Hampshire, West Sussex and Berkshire, centred on the capital Calleva Atrebatum (modern Silchester). They were bordered to the north by the Dobunni and Catuvellauni; to the east by the Regni; and to the south by the Belgae.

The settlement of the Atrebates in Britain was not a mass population movement. Archaeologist Barry Cunliffe argues that they "seem to have comprised a series of indigenous tribes, possibly with some intrusive Belgic element, given initial coherence by Commius". It is possible that the name "Atrebates", as with many "tribal" names in this period, referred only to the ruling house or dynasty and not to an ethnic group; Commius and his followers, after arriving in Britain, may have established a power-base and gradually expanded their sphere of influence, creating what was in effect a proto-state. However, during Caesar's first expedition to Britain in 55 BC, after the Roman cavalry had been unable to cross the Channel, Commius was able to provide a small group of horsemen from his people, suggesting that he may have already had kin in Britain at that time. After this time, the Atrebates were recognized as a client kingdom of Rome.

Coins stamped with Commius's name were issued from Calleva from ca. 30 BC to 20 BC. Some coins are stamped "COM COMMIOS": interpreting this as "Commius son of Commius", and considering the length of his apparent floruit, some have concluded that there were two kings, father and son, of the same name.

Three later kings of the British Atrebates name themselves on their coins as sons of Commius: Tincomarus, Eppillus and Verica. Tincomarus seems to have ruled jointly with his father from about 25 BC until Commius's death in about 20 BC. After that, Tincomarus ruled the northern part of the kingdom from Calleva, while Eppillus ruled the southern half from Noviomagus (Chichester). Numismatic and other archeological evidence suggests that Tincomarus took a more pro-Roman stance than his father, and John Creighton argues from the imagery on his coins that he was brought up as an obses (diplomatic hostage) in Rome under Augustus.

Augustus's Res Gestae mentions two British kings presenting themselves to him as supplicants, probably ca. 7 AD. The passage is damaged, but one is probably Tincomarus (the other is Dubnovellaunus, of either the Trinovantes or the Cantiaci). It appears Tincomarus was ousted by his brother, and from this point Epillus's coins are marked "Rex", indicating that he was recognised as king by Rome.

In about 15, Eppillus was succeeded by Verica (at about the same time, a king by the name of Eppillus appears as ruler of the Cantiaci in Kent). But Verica's kingdom was being pressed by the expansion of the Catuvellauni under Cunobelinus. Calleva fell to Cunobelinus's brother Epaticcus by about 25. Verica regained some territory following Epaticcus's death in about 35, but Cunobelinus's son Caratacus took over the campaign and by the early 40s the Atrebates were conquered. Verica fled to Rome, giving the new emperor Claudius the pretext for the Roman conquest of Britain.

After the Roman conquest, part of the Atrebates' lands were organized into the pro-Roman kingdom of the Regni under Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus, who may have been Verica's son. The tribal territory was later organised as the civitates (administrative districts within a Roman province) of the Atrebates, Regni and possibly the Belgae.

However it is possible that the Atrebates were a family of rulers (dynasty), as there is no evidence for a major migration from Belgium to Britain.

List of kings of the Atrebates

- Commius, 57 - c. 20 BC

- Tincomarus, c. 20 BC - AD 7, son of Commius

- Eppillus, AD 8 - 15, brother of Tincomarus

- Verica, 15 - 40, brother of Eppillus

- Claudius Cogidubnus

- Full Roman annexation.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Schön & Todd 2006.

- 1 2 3 Drinkwater 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Frere & Millett 2015.

- ↑ Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:4; Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:106.

- ↑ Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:3:5.

- ↑ Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:4.

- ↑ Cassius Dio. Rhōmaïkḕ Historía, 40:43.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum, oc 42:40.

- ↑ Falileyev 2010, s.v. Atrebates.

- ↑ Lambert 1994, p. 35; Delamarre 2003, pp. 59, 301–302; Busse 2006, p. 198; Matasović 2009, pp. 46, 388; see Lambert 1997, p. 398 for Atrebas/Atrebatis.

- ↑ Nègre 1990, pp. 152, 424.

- 1 2 3 Wightman 1985, p. 29.

- 1 2 Delamarre 2003, pp. 114, 233.

- ↑ Caesar, De Bello Gallico, 2.4

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Drinkwater, John F. (2015). "Atrebates (1), a tribe of Gallia Belgica". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.939. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Frere, Sheppard S.; Millett, Martin (2015). "Atrebates (2), a Gallic tribe of southern Britannia". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.940. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1994). La langue gauloise: description linguistique, commentaire d'inscriptions choisies. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-089-2.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (1997). "Gaulois tardif et latin vulgaire". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 49–50 (1): 396–413. doi:10.1515/zcph.1997.49-50.1.396. ISSN 1865-889X. S2CID 162600621.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.

- Schön, Franz; Todd, Malcolm (2006). "Atrebates". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e207110.

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.

Primary sources

- Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti

- Dio Cassius, Roman History

- Sextus Julius Frontinus, Strategemata

- Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallico

- Ptolemy, Geography

Further reading

- Bean, Simon C. (1994). The coinage of Atrebates and Regni (Ph.D. thesis). University of Nottingham.

- John Creighton, Coins and Power in Late Iron Age Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- Barry Cunliffe, Iron Age Britain. London: B. T. Batsford/English Heritage, 1995 ISBN 0713471840

- Sheppard Frere, Britannia. 1967, revised 1978, 3rd ed. 1987