| Austroraptor Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

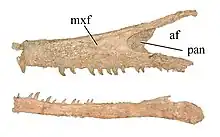

| Maxilla and dentary of the holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Unenlagiinae |

| Genus: | †Austroraptor Novas et al., 2008 |

| Species: | †A. cabazai |

| Binomial name | |

| †Austroraptor cabazai Novas et al., 2008 | |

Austroraptor (/ˌɔːstroʊˈræptər/ AW-stroh-RAP-tər) is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Campanian and Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Argentina.

Austroraptor was a large, moderately-built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, estimated at 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long. It is one of the largest dromaeosaurids known, with only Achillobator, Dakotaraptor, and Utahraptor approaching or surpassing it in length.

Discovery and naming

The type specimen of Austroraptor cabazai, holotype MML-195, was recovered in the Bajo de Santa Rosa locality of the Allen Formation, in Río Negro, Argentina. The specimen was collected in 2002 by the team of Fernando Emilio Novas of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. It consists of a fragmentary skeleton including parts of the skull, lower jaw, a few neck and torso vertebrae, some ribs, a humerus, and assorted bones from both legs. The specimen was prepared by Marcelo Pablo Isasi and Santiago Reuil. In 2008, the type species Austroraptor cabazai was named and described by Fernando Emilio Novas, Diego Pol, Juan Canale, Juan Porfiri and Jorge Calvo. The genus name Austroraptor means "Southern Thief," and is derived from the Latin word auster meaning "the south wind" and the Latin word raptor meaning "thief." The specific name cabazai was chosen in honor of Héctor "Tito" Cabaza, who founded the Museo Municipal de Lamarque where the specimen was partially studied.[1]

In 2012, Phil Currie and Ariana Paulina-Carabajal referred a second specimen to Austroraptor cabazai, MML-220, that was found in 2008. This specimen, a partial skeleton with the skull of an adult individual slightly smaller than the holotype, is also housed in the collection of the Museo Municipal de Lamarque in Argentina. It complements the holotype in several elements, mainly the lower arm, hand and foot.[2]

Description

It is the largest dromaeosaur to be discovered in the Southern Hemisphere; Novas et al. estimated that Austroraptor measured 5 m (16 ft) in length from head to tail.[1] Gregory S. Paul later estimated its length at 6 m (20 ft) and weight of 300 kg (660 lb).[3] However, Thomas R. Holtz Jr. has suggested that its weight is comparable to a lion, around 91–227 kg (200.6–500.4 lb).[4]

The skull is low and elongated, much more so than that of other dromaeosaurs, and measures 80 cm (31 in). Austroraptor has conical, non-serrated teeth, which Novas et al. compared to those of spinosaurids, based on how the enamel of the surface of its teeth is fluted.[1] Austroraptor shares a trait that is unique to it and to Adasaurus: the descending process of the lacrimal bones curves anteriorly to a large degree.[5] Austroraptor has a bizarre morphology in its pedal phalanges, which are strangely disproportionate. Phalanx IV-2 is over twice the width of phalanx II-2, and nearly three times the expected width based on similarly sized members of its taxonomic family. This has suggested to some researchers that the holotype specimen is a paleontological chimera; however, there is no uncertainty about the affinity of the taxon, so a chimera hypothesis can not be assured.[5]

Several of Austroraptor's skull bones bear some resemblance to those of the smaller troodontids. The front limbs of Austroraptor were short for a dromaeosaur, with its humerus less than half the length of its femur. Among the Dromaeosauridae, only this genus, Tianyuraptor, Zhenyuanlong and Mahakala have similarly reduced forelimbs.[1][5] The relative length of its arms has caused Austroraptor to be compared to another, more famous short-armed dinosaur, Tyrannosaurus, though there is no close relationship between the two taxa.[6]

Distinguishing traits

However little of the entire skeleton was found, the bones that are available for analysis possess some distinct characteristics that differentiate Austroraptor from other dromaeosaurs. Austroraptor is particularly notable because of its relatively short forearms, which are much shorter in proportion when compared to the majority of the members of Dromaeosauridae. According to Novas et al. 2008, Austroraptor can be distinguished based on the following characteristics:[1]

- A lacrimal that is highly pneumatized, with the descending process strongly curved rostrally, and with a caudal process flaring out horizontally above the orbit.

- The lack of a dorsomedial process on the postorbital bone for articulation with the frontal bone, and with the squamosal process extremely reduced.

- The maxillary and dentary teeth are small, conical, devoid of serrations and fluted.

- The humerus is short, at approximately 46% of length of the femur.

- The pedal phalanx II-2 is transversely narrow, contrasting with the extremely robust phalanx IV-2.[Note 1][Note 2][Note 3][Note 4]

In 2012, comparison with a second specimen showed that the fourth toe was not especially broad; the purported second phalanx had in fact been a first phalanx.[2]

Classification

A cladistic analysis of the holotype specimen's anatomical features by the describers placed Austroraptor within the subfamily Unenlagiinae of Dromaeosauridae. This assignment was based on characteristics observed in the bones of the skull, the teeth, and the geometry and formation of the specimen's vertebral elements. It was determined that Austroraptor was a close relative of the unenlagiine dromaeosaur Buitreraptor, with which it shares certain derived characteristics of the neck vertebrae.[1]

The following cladogram is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Turner, Makovicky and Norell in 2012, showing the relationships of Austroraptor among the other genera assigned to the taxon Unenlagiinae:[5]

| Unenlagiinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Cau et al. 2017 published a phylogenetic analysis of the Dromaeosauridae during the description of Halszkaraptor, in which members of the Unenlagiinae are classified as:[7]

| Unenlagiinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||

In 2019, during the description of Hesperornithoides, many paravian groups were examined for the inclusion of the new genus. In this analysis, Austroraptor is found to be a more basal member of Unenlagiinae.[8]

| Unenlagiinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2021, Brum and colleagues classified Ypupiara as a sister taxon to Austroraptor.[9]

| Unenlagiinia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

It has been suggested that unenlagiines had better capacities for running and pursuit predation than other dromaeosaurids. While Laurasian dromaeosaurids (Eudromaeosauria) were more stocky and had shorter legs and had an active predatory lifestyle, unenlagiines could likely maintain high speeds for extended amounts of time because they were more gracile. Unenlagiines have modified metatarsals that resemble those of microraptorines: they are relatively thin and lengthened. Based on these adaptations, it is likely that unenlagiines preyed on small, fast animals, although the exact animals are unknown. Buitreraptor features particular traits that can be attributed to specific hunting methods.[10]

Models for Buitreraptor propose that it hunted by traveling large distances in pursuit of prey, which may explain the long-legged trait shared by various genera of Unenlagiidae. Buitreraptor is characterized by its long forelimbs and hands; it likely relied on them to restrain prey and the curved claw of the second pedal digit would have injured or killed the victim. Buitreraptor probably swallowed its prey whole due to its lack of serrated teeth with flesh-tearing capabilities; the teeth functioned to simply hold prey.[10]

The same model was proposed for the much larger Austroraptor with few exceptions:[10]

- It would not have used its arms to handle prey, due to their relatively small size.

- Its teeth were conical and probably stronger, so it may have been able to use them for hunting larger prey.

The teeth of Austroraptor are conical and lacking denticles, similarly to those of spinosaurids.[1] Since it probably had a subarctometatarsal condition and similar hindlimb lengths compared to Buitreraptor, Austroraptor likely had well-developed cursorial capacities.[10] In 2021, Brum and colleagues suggested that unenlagiines such as Austroraptor and its sister taxon Ypupiara likely consumed fish for a considerable part of their diet, possibly even as a main food source, based on their non-serrated conical teeth that are similar to those of piscivorous tetrapods including gavialoids, spinosaurids, anhanguerids, etc.[9]

Paleoecology

The holotype specimen was found in terrestrial sediments that were deposited during the Campanian–Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period.[1] Thomas R. Holtz Jr. has estimated that Austroraptor lived between 78 million and 66 million years ago, until the end of the Mesozoic era.[4] Austroraptor shared its paleoenvironment in the Allen Formation with diverse dinosaurs and early mammals.[11] The discovery of Austroraptor increases the understanding of ecological and morphological diversity among unenlagiines, demonstrating that members of the subfamily included giant short-armed and small long-armed members, and suggesting that during the end of the Cretaceous large coelurosaurs became common after the decreasing dominance of carcharodontosaurids.[1] This genus represents the earliest record of Gondwanan dromaeosaurids, and supports the fact that large dromaeosaurids took the role of large predators alongside abelisaurids such as Quilmesaurus, Aucasaurus and Carnotaurus.[1]

During his description of Pellegrinisaurus, Salgado suggested that large titanosaurs and theropods inhabited interior environments of the region, and contemporaneous hadrosaurids and the titanosaur Aeolosaurus inhabited coastal lowlands.[12] The diversity among titanosaurs indicates that the Allen Formation had environments that supported a great range of herbivorous dinosaurs.[13] Other contemporaneous paleofauna includes the titanosaurs Laplatasaurus, Rocasaurus and Saltasaurus, the bird Limenavis,[11] and the hadrosaurids Bonapartesaurus, Kelumapusaura, and Lapampasaurus.[14][15]

See also

Notes

- ↑ This condition differs from that Laurasian Dromaeosaurids, but is unknown for other Unenlagiines

- ↑ A condition also observed in Buitreraptor

- ↑ A smaller ratio than in other Dromaeosaurids and Paravians

- ↑ This condition differs from that of other Dromaeosaurids including Unenlagiines, but resembles the condition observed in advanced Troodontids

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Novas, F. E.; Pol, D.; Canale, J. I.; Porfiri, J. D.; Calvo, J. O. (2008). "A bizarre Cretaceous theropod dinosaur from Patagonia and the evolution of Gondwanan dromaeosaurids". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1659): 1101–7. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1554. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 2679073. PMID 19129109.

- 1 2 Currie, P.; Carabajal, A. P. (2012). "A New Specimen of Austroraptor cabazai Novas, Pol, Canale, Porfiri and Calvo, 2008 (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Unenlagiidae) from the Latest Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Río Negro, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 49 (4): 662–667. doi:10.5710/AMGH.30.8.2012.574. hdl:11336/9090. S2CID 129058582.

- ↑ Paul, G. S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 138.

- 1 2 Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. Supplementary Information 2012

- 1 2 3 4 Turner, A. H.; Makovicky, P. J.; Norell, M. A. (2012). "A Review of Dromaeosaurid Systematics and Paravian Phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371 (371): 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. S2CID 83572446.

- ↑ "Researchers find short-armed raptor in Argentina". Reuters. 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ↑ Cau, A.; Beyrand, V.; Voeten, D.; Fernandez, V.; Tafforeau, P.; Stein, K.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Currie, P.; Godrfroit, P. (6 December 2017). "Synchrotron scanning reveals amphibious ecomorphology in a new clade of bird-like dinosaurs". Nature. 552 (7685): 395–399. Bibcode:2017Natur.552..395C. doi:10.1038/nature24679. PMID 29211712. S2CID 4471941.

- ↑ Hartman, Scott; Mortimer, Mickey; Wahl, William R.; Lomax, Dean R.; Lippincott, Jessica; Lovelace, David M. (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- 1 2 Brum, Arthur S.; Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Bandeira, Kamila L.N.; Souza, Lucy G.; Campos, Diogenes A.; Kellner, Alexander W.A. (2021). "A new Unenlagiinae (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 2075–2099. doi:10.1002/spp2.1375.

- 1 2 3 4 Gianechini, F. A.; Ercoli, M. D.; Díaz-Martinez, I. (2020). "Differential locomotor and predatory strategies of Gondwanan and derived Laurasian dromaeosaurids (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Paraves): Inferences from morphometric and comparative anatomical studies". Journal of Anatomy. 236 (5): 772–797. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4382H. doi:10.1111/joa.13153. PMC 7163733. PMID 32023660.

- 1 2 Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (2007). The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press. p. 604.

- ↑ Salgado, L. (1996). "Pellegrinisaurus powelli nov. gen. et sp. (Sauropoda, Titanosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Lago Pellegrini, Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 33 (4): 355–365. ISSN 1851-8044.

- ↑ Garcia, R. A.; Salgado, R. (2013). "The Titanosaur Sauropods from the Late Campanian—Early Maastrichtian Allen Formation of Salitral Moreno, Río Negro, Argentina" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (2): 269–284. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0055. ISSN 0567-7920. S2CID 55411436.

- ↑ Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Powell, J. E. (2017). "Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, a new hadrosaurine dinosaur from South America: implications for phylogenetic and biogeographic relations with North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (2): 1–16. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1289381. S2CID 90963879.

- ↑ Coria, R. A.; Riga, B. G.; Casadío, S. (2012). "Un nuevo hadrosáurido (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) de la Formación Allen, provincia de La Pampa, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 49 (4): 552–572. doi:10.5710/AMGH.9.4.2012.487. S2CID 131521822.

External links

Media related to Austroraptor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Austroraptor at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Austroraptor at Wikispecies

Data related to Austroraptor at Wikispecies

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)