Topeng Cirebon dance performance | |

| Native name | ᬢᭀᬧᬾᬂ (Balinese) ᮒᮧᮕᮨᮔᮌ (Sundanese) ꦠꦺꦴꦥꦺꦁ (Javanese) Tari Topeng (Indonesian) |

|---|---|

| Instrument(s) | Gamelan, Kendhang, Suling |

| Origin | Indonesia |

Topeng (from Balinese: ᬢᭀᬧᬾᬂ, Sundanese: ᮒᮧᮕᮨᮔᮌ, and Javanese: ꦠꦺꦴꦥꦺꦁ, romanized: topeng, lit. 'mask') is a dramatic form of Indonesian dance in which one or more mask-wearing, ornately costumed performers interpret traditional narratives concerning fabled kings, heroes and myths, accompanied by gamelan or other traditional music instruments.[1] Topeng dance is a typical Indonesian dance that can be found in various regions in Indonesia. Topeng dance has the main characteristic that the dancers use masks to cover their faces. The dance will usually be performed by one dancer or a group of dancers.

Topeng is widely used in dances that are part of traditional ceremonies or the retelling of ancient stories from the ancestors. It is believed that topeng is closely related to ancestral spirits which are considered interpretations of gods. In some tribes, topeng still adorns various daily artistic and customary activities. Topeng dance is a performance dance full of meaningful symbols that are expected to be understood by the audience. These symbols are conveyed through the colors of the masks, the expressions of the masks, and the accompanying music. The meaning conveyed can be in the form of leadership values, love, wisdom, and other meanings conveyed through the medium of dance movements.[2]

In 2010, topeng Cirebon from Cirebon, West Java was recognized as National Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indonesia by the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture.[3]

Etymology

The term topeng is the Javanese word for "mask" or "dance-drama that uses the mask".[4] In modern daily Javanese and Indonesian vocabulary, tari topeng or "topeng dance" refer to dance or dance-drama performance that uses a mask.

History

Indonesian masked dance predates Hindu-Buddhist influences. Native Indonesian tribes still perform traditional masked-dances to represent nature, as the Hudoq dance of the Dayak people of Kalimantan, or to represent ancestor spirits. With the arrival of Hinduism in the archipelago, the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics began to be performed in masked-dance.

The oldest known record that concerns Topeng dance is from the ninth century. Around 840 AD an Old Javanese (Kawi) inscriptions called Jaha Inscriptions issued by Maharaja Sri Lokapala form Medang Kingdom in Central Java mentions three sorts of performers: atapukan, aringgit, and abanol. Atapukan means Mask dance show, Aringgit means Wayang puppet show, and abanol means joke art.

On the inscription of Candi Perot (850 AD), the word "manapel" is written from the word "tapuk" or "tapel" which means mask. On the Bebetin inscription (896 AD) there is the word "patapukan" which means a mask association. In the Mantiasih inscription (904 AD) there are the terms "matapukan" and "manapukan" which means that they relate to the drama presentation of masks.

The most popular storyline of topeng dance, however, derived from the locally developed Javanese Panji cycles, based on the tales and romance of Prince Panji and Princess Chandra Kirana, set in the 12th-century Kadiri kingdom.

One of the earliest written records of topeng dance is also found in the 14th-century poem Nagarakretagama, which describes King Hayam Wuruk of Majapahit — wearing a golden mask — as an accomplished topeng dancer.[5] The current topeng dance form arose in the 15th century in Java and Bali where it remains prevalent, but it is also found in other Indonesian islands — such as Madura (near East Java). Various topeng dances and styles have developed in various places in the Indonesian archipelago, notably in Cirebon, Yogyakarta, Malang and Bali. The well-developed topeng technique is now studied in universities in Europe and America.

Variations

Balinese topeng

It is believed that the use of masks is related to the cult of the ancestors, which considered dancers the interpreters of the gods. Topeng performances open with a series of non-speaking masked characters which may not be related to the story to be performed. These traditional masks often include Topeng Manis (a refined hero), Topeng Kras (a martial, authoritarian character), and Topeng Tua (an old man who may joke and draw out the audience).

The story is narrated from a penasar, a jawless half-mask that enables the actor to speak clearly. In group topeng, there are usually two penasars providing two points of view. The performance alternates between speaking and non-speaking characters, and can include dance and fight sequences as well as special effects (sometimes provided by the gamelan). It is almost always wrapped up by a series of comic characters introducing their own views. The narrators and comic characters frequently break Western conventions of storytelling by including current events or local gossip to get a laugh.

In topeng, there is a conscious attempt to include many, sometimes contradictory, aspects of the human experience: the sacred and the profane, beauty and ugliness, refinement and caricature.[6] A detailed description and analysis of topeng pajegan, the one-man form of topeng, is available in Masked Performance[7] by John Emigh, a Western theater professor who has become a performer of Balinese topeng.

- Some figures in Topeng Bali

Topeng Tua

Topeng Tua Topeng Telek

Topeng Telek Topeng Sidakarya

Topeng Sidakarya

Banjarese topeng

The topeng also calls topeng barikin from South Kalimantan.

Batak topeng

- Some figures in Topeng Batak

Batak masked dance during the festival of the dead, circa 1930

Batak masked dance during the festival of the dead, circa 1930 Topeng Batak

Topeng Batak Topeng Batak

Topeng Batak

Betawi topeng

Betawi mask dance or tari topeng Betawi is a theatrical form of dance-drama of Betawi people in Jakarta, Indonesia.[8] This dance-drama encompasses dance, music, bebodoran (comedy) and lakon (drama).[9] The Betawi mask dance demonstrates the theme of Betawi society life which represented in the form of dance and drama. It is called mask dance because the dancers using topeng (mask) during dancing which Betawi people believed that the topeng has magical powers.[10]

Sundanese & Cirebonese (West Java) topeng

Cirebonese topeng dance is a local indigenous art form of Cirebon in Java, including Indramayu and Jatibarang, West Java and Brebes, Central Java. There is a lot of variety in Cirebon mask dance, both in terms of the dance style and the stories to be conveyed. The mask dance can be performed by solo dancers or it can be performed by several people. Graceful hand and body movements, and musical accompaniment dominated by drums and fiddle, are hallmarks of the art form. Cirebon mask dance might depict the story of Prince Panji from 15th-century East Java, or another Majapahit story. Topeng Klana Kencana Wungu is a Cirebon mask dance in the Parahyangan mask style that depicts the story of Queen Kencana Wungu of Majapahit being chased by the grotesque and rough King Minak Jingga of Blambangan. The Sundanese topeng kandaga dance is similar to and influenced by Cirebon topeng, where the dancers wear red masks and costumes.

- Some figures in Topeng Cirebon

Topeng Panji

Topeng Panji Topeng Cirebon Performance

Topeng Cirebon Performance Topeng Klana

Topeng Klana

Dayak topeng

Hudoq is a masked dance performed during Erau harvest thanksgiving festival of many of sub-groups of the Dayak ethnic group of East Kalimantan province, Indonesia. The Hudoq culture and performance is indigenous among Dayak population of East Kalimantan province.

- Some figures in Topeng Dayak

Topeng Hudoq

Topeng Hudoq Topeng Hudoq

Topeng Hudoq

Javanese topeng

Malangan topeng

In East Java, topeng dance is called wayang gedog and is the best known art form from East Java's Malang Regency. Wayang gedog theatrical performances include themes from the Panji cycle stories from the kingdom of Janggala, and the players wear masks known as wayang topeng or wayang gedog. The word gedog comes from kedok which, like topeng, means "mask".

These performances center on a love story about Princess Candra Kirana of Kediri and Raden Panji Asmarabangun, the legendary crown prince of Janggala. Candra Kirana was the incarnation of Dewi Ratih (the Hindu goddess of love) and Panji was an incarnation of Kamajaya (the Hindu god of love). Kirana's story has been given the title Smaradahana ("The fire of love"). At the end of the complicated story they finally marry and bring forth a son named Raja Putra.

- Some figures in Topeng Malang

Malangan topeng mass dance

Malangan topeng mass dance Topeng in wayang gedog performance

Topeng in wayang gedog performance Wayang topeng Malang

Wayang topeng Malang

Surakartan topeng

The topeng of the Surakarta Sunanate court is similar in style and theme to the Yogyakarta variants. Differences are seen in the craftmanship of masks; facial hair is represented with hair or fibre, while the Yogyakarta style uses black paint. Similarly to Yogyakarta, the Sukarta topeng punakawan (jester) often uses a jawless half-mask.

Yogyakartan topeng

In Yogyakarta tradition, the mask dance is part of wayang wong performances. Composed and created by Sultan Hamengkubuwono I (1755–1792), certain characters such as the wanara (monkey) and denawa (giant) in Ramayana and Mahabharata use masks, while the knight and princesses do not wear masks. The punakawan (jester) might use a half-mask (a mask without a jaw) so he can speak freely and clearly. Significantly here, the mustache is painted in black. The Topeng Klono Alus, Topeng Klono Gagah, and Topeng Putri Kenakawulan dances are classical Yogyakarta court dances derived from the story of Raden Panji from the 15th-century Majapahit legacy. The Klono Alus Jungkungmandeya and Klono Gagah Dasawasisa are masked dances adapted from Mahabharata stories.

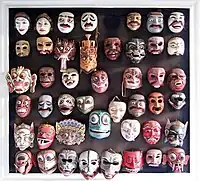

Gallery

- Some other Examples of Topeng dance in Indonesia

- Some Examples of Topeng in Indonesia

See also

Notes

- ↑ "History and Etymology for Topeng". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ "Tari Topeng, Permainan Watak Penuh Makna". Indonesia Kaya. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ↑ "Warisan Budaya Takbenda, Penetapan". Cultural Heritage, Ministry of Education and Culture of Indonesia. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ↑ "History, and Etymology for Topeng". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ "Sosok Rahwana dalam Tari Topeng Kelana" (in Indonesian). Indonesia Kaya. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ "The Secret of Masks". Bohème Magazine Online. June 2003. Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Emigh, John (1996). Masked Performance: The Play of Self and Other in Ritual and Theatre. ISBN 081221336X.

- ↑ "Tari Topeng Betawi Tarian Tradisional dari Jakarta". Negeriku Indonesia. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ ASEAN (5 September 2020). "Traditional Betawi Mask Dance, Traditional Dance From Jakarta?". Indonesiar. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Sacred Betawi Mask Dance". Indonesia Tourisme. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

External links

- Information on topeng dances from the program notes of a performance in Glasgow in 2003

- Various examples of Indonesian topeng masks Archived 2020-08-12 at the Wayback Machine