Balinese art is an art of Hindu-Javanese origin that grew from the work of artisans of the Majapahit Kingdom, with their expansion to Bali in the late 14th century. From the sixteenth until the twentieth centuries, the village of Kamasan, Klungkung (East Bali), was the centre of classical Balinese art. During the first part of the twentieth century, new varieties of Balinese art developed. Since the late twentieth century, Ubud and its neighboring villages established a reputation as the center of Balinese art.

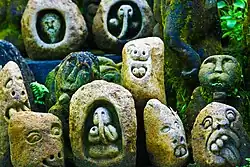

Ubud and Batuan are known for their paintings, Mas for their woodcarvings, Celuk for gold and silver smiths, and Batubulan for their stone carvings. Covarrubias[1] describes Balinese art as, "... a highly developed, although informal Baroque folk art that combines the peasant liveliness with the refinement of classicism of Hinduistic Java, but free of the conservative prejudice and with a new vitality fired by the exuberance of the demonic spirit of the tropical primitive". Eiseman correctly pointed out that Balinese art is carved, painted, woven, and prepared into objects intended for everyday use rather than as object d 'art.[2] Balinese paintings are notable for their highly vigorous yet refined, intricate art that resembles baroque folk art with tropical themes.[3]

Recent History

Before the 1920s, Balinese traditional paintings were mainly found in what is now known as the Kamasan or Wayang style. These are visual presentations of narratives, especially of the Hindu-Javanese epics——the Ramayana and Mahabharata——as well as several indigenous stories, such as the Malat, depicting Panji narratives and the Brayut story.[4]

These two-dimensional drawings are traditionally drawn on cloth or bark paper (Ulantaga or daluwang paper), and sometimes on wood, with natural dyes. The coloring is limited to available natural dyes: red from volcanic rocks, ochre, blue from indigo, and black from soot. In addition, the rendering of the figures and ornamentations must follow strictly prescribed rules, since they are mostly produced for religious articles and temple hangings. These paintings are produced collaboratively, and therefore mostly anonymously.

There were many experiments with new types of art by Balinese from the late nineteenth century onwards. These experiments were stimulated by access to new materials (western paper and imported inks and paint), and by the 1930s, new tourist markets stimulated many young Balinese to be involved in new types of art.

In the 1920s, with the arrival of many Western artists, Bali became an artist enclave (as Tahiti was for Paul Gauguin) for avant-garde artists such as Walter Spies (German), Rudolf Bonnet (Dutch), Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur (Belgian), Arie Smit (Dutch), Theo Meier (Swiss) and Donald Friend (Australian) in more recent years. Most of these Western artists had very little influence on the Balinese until the post-World War Two period, although some accounts over-emphasize the Western presence at the expense of recognizing Balinese creativity.

On his first visit to Bali in 1930, the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias noted that local paintings served primarily religious or ceremonial functions. They were used as decorative cloths to be hung in temples and important houses, or as calendars to determine children's horoscopes. Yet within a few years, he found the art form had undergone a "liberating revolution." Where they had once been severely restricted by subject (mainly episodes from Hindu mythology) and style, Balinese artists began to produce scenes from rural life. These painters had developed increasing individuality.[1]

This groundbreaking period of creativity reached a peak in the late 1930s. A stream of famous visitors, including Charlie Chaplin and the anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, encouraged the talented locals to create highly original works. During their stay in Bali in the mid-1930s, Bateson and Mead collected over 2000 paintings, predominantly from the village of Batuan, but also from the coastal village of Sanur.[5] Among Western artists, Spies and Bonnet are often credited for the modernization of traditional Balinese paintings. From the 1950s onwards Balinese artists incorporated aspects of perspective and anatomy from these artists.[6] More importantly, they acted as agents of change by encouraging experimentation and promoting departures from tradition. The result was an explosion of individual expression that increased the rate of change in Balinese art. The 1930s styles were consolidated in the 1950s, and in more recent years have been given the confusing title of "modern traditional Balinese painting". The Ubud painters, although a minority amongst the artists working in the 1930s, became the representatives of the new style thanks to the presence of the great artist Gusti Nyoman Lempad in that village, and to the patronage of the traditional rulers of Ubud. The key points of the Ubud Style included a concentration on the depiction of daily Bali life and drama; the change of the patron of these artists from the religious temples and royal houses to western tourists/collectors; shifting the picture composition from multiple to single focus.[7] Despite the adoption of modern Western painting traditions by many Balinese and Indonesian painters, "modern traditional Balinese painting" is still thriving and continues by descendants/students of the artists of the pre-war modernist era (1928-1942). The schools of modern traditional Balinese painting include Ubud, Batuan, Sanur, Young Artist, and Keliki schools of painting.[7]

Modern traditional painting

The pre-war modernization of Balinese art emanated from three villages: Ubud, where Spies settled, Sanur on the southern coast, and Batuan, a traditional hub of musicians, dancers, carvers, and painters. The artists painted mostly on paper, though canvas and board were also used. Often, the works featured repetitive clusters of stylized foliage or waves that conveyed a sense of texture, even perspective. Each village evolved a style of its own. Ubud artists made more use of open spaces and emphasized human figures. Sanur paintings often featured erotic scenes and animals, and work from Batuan was less colorful but tended to be busier.[8]

Ubud painting

.jpg.webp)

Ubud became a center for art in the 1930s, under the patronage of the lords of Ubud, who rose to power at the end of the nineteenth century. Before the 1930s, traditional wayang-style paintings from other villages may have been found in Ubud but were more influential in the nearby village of Peliatan, which is nowadays classified as part of Ubud. Significant Ubud artists were already adapting versions of the wayang style by the end of the 1920s, notably Ida Bagus Kembeng of Tebesaya, who may have studied with relatives in nearby Tampaksiring village. I Gusti Nyoman Lempad, who had come to Ubud under the patronage of its ruling lord, changed from being an architect and sculptor to executing outstanding drawings around 1931. Anak Agung Gde Sobrat of Ubud also began to paint around this time. These and other artists were given materials and opportunities to sell their work by the resident European artists Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet. They developed experimental styles which European commentators identified as a new, modern type of Balinese art, differentiated from the traditional art which is governed by strict rules of religious iconography.

Under the patronage of the Ubud royal family, especially Tjokorda Gde Agung Sukawati, and with Rudolf Bonnet as a chief consultant, the Pitamaha Art Guild was founded in 1936 as a way to professionalize Balinese painting. Its mission was to preserve the quality of Balinese Art in the rush of tourism to Bali. The board members of Pitamaha met regularly to select paintings submitted by its members, and to conduct exhibitions throughout Indonesia and abroad. Between 1936 and 1939, Bonnet organized significant exhibitions of this modern Balinese art in the Netherlands, with a smaller exhibition in London. Pitamaha was active until the Second World War came to Bali in 1942. Ubud artists who were members of Pitamaha came from Ubud and its surrounding villages: Pengosekan, Peliatan, and Tebasaya. Among them, besides those mentioned above, were: The three sons of Ida Bagus Kembeng: Ida Bagus Wiri, Ida Bagus Made, and Ida Bagus Belawa; Tjokorda Oka of the royal house of Peliatan; Sobrat and his family members, including Anak Agung Gde Meregeg, I Dewa Putu Bedil, I Dewa Nyoman Leper, Anak Agung Dana of Padangtegal; and I Gusti Ketut Kobot, his brother I Gusti Made Baret, I Wayan Gedot, Dewa Putu Mokoh of Pengosekan. Artists from other areas also participated, including Pan Seken from Kamasan, I Gusti Made Deblog from Denpasar, and some of the Sanur artists.

Although short-lived, Pitamaha is identified with the outpouring of modern art of the 1930s which preceded it, and with succeeding developments in art. Artists from Ubud have continued the Pitamaha tradition. Important among these Ubud Artists are Ida Bagus Sena (nephew of Ida Bagus Made Poleng), A.A Gde Anom Sukawati (son of A.A Raka Pudja), I Ketut Budiana, I Nyoman Kayun and I Nyoman Meja. Budiana is the artist with one of the most impressive solo exhibition track records. His paintings are collected by the Fukuoka Museum of Arts, Bentara Budaya Jakarta, Museum Puri Lukisan, Neka Museum, and Arma Museum. Ida Bagus Sena also has developed a unique style and has a deep understanding of Balinese philosophy in his paintings. Anom Sukawati is Balinese most successful colorist. I Nyoman Meja developed a style that is closely copied by several of his students. I Nyoman Kayun received the Bali Bangkit award in 2008.

Batuan painting

The Batuan School of Painting is practiced by artists in the village of Batuan, which is situated 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to the south of Ubud. The Batuan artisans are gifted dancers, sculptors, and painters. Leading artists of the 1930s included I Nyoman Ngendon, and some members of leading Brahman families, including Ida Bagus Made Togog. Other major Batuan artists from the pre-modernist era include I Dewa Nyoman Mura (1877-1950) and I Dewa Putu Kebes (1874-1962), who was known as sanging; traditional Wayang-style painters for temples' ceremonial textiles.

The Western influence in Batuan did not reach the intensity it had in Ubud.[5] According to Claire Holt, the Batuan paintings were often dark, crowded representations of either legendary scenes or themes from daily life, but they portrayed above all fearsome nocturnal moments when grotesque spooks, freakish animal monsters, and witches accosted people. This is particularly true for paintings collected by Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson during their field studies in Bali from 1936 to 1939.[5] Gradations of black to white ink washes laid over most of the surface, to create an atmosphere of darkness and gloom. In the later years, the designs covered the entire space, which often contributed to the crowded nature of these paintings.

Among the early Batuan artists, I Ngendon (1903-1946) was considered the most innovative Batuan School painter.[6] Ngendon was not only a good painter but a shrewd businessman and political activist. He encouraged and mobilized his neighbors and friends to paint for tourist consumption. His ability in portraiture played an important role in teaching his fellow villagers in Batuan more than Spies and Bonnet.[6] The major Batuan artists from this period were: I Patera (1900-1935), I Tombos (b. 1917), Ida Bagus Togog (1913-1989), Ida Bagus Made Jatasura (1917-1946), Ida Bagus Ketut Diding (1914-1990), I Made Djata (1920-2001), and Ida Bagus Widja (1912-1992). The spirit of the Pitamaha period is still strong and continues by contemporary Batuan Artists such as I Made Budi, I Wayan Bendi (b. 1950), I Ketut Murtika (b. 1952), I Made Sujendra (b. 1964), and many others. I Made Budi and I Wayan Bendi paintings capture the influence of tourism in modern life in Bali. They place tourists with their cameras, riding a motorbike or surfing during Balinese traditional village activities. The dichotomy of modern and traditional Balinese life is contrasted starkly in harmony. I Ketut Murtika still paints the traditional story of Mahabharata and Ramayana in painstaking details with subdued colors. His painting of the Wheel of Life viewed from the Balinese belief system shows his mastery of local legends and painstaking attention to detail.[9]

Sanur painting

Unlike Ubud and Batuan which are located in the inland of Bali, Sanur is a beach resort. Sanur was the home of the well-known Belgian artist Le Mayeur de Mepres, who lived with a Balinese wife (Ni Polok) and had a beach house on Sanur beach, although he had no interaction with local artists.

Tourists in the 1930s came to Bali on cruise ships docked in Sanur and made side trips to Ubud and neighboring tourist sites. Its prime location provided the Sanur artist with ready access to Western tourists who frequented the shop of the Neuhaus Brothers who sold Balinese souvenirs and had a tropical fish aquarium. The Neuhaus brothers became the major dealers of Sanur paintings and other local art. The beach around Sanur, full of outriggers and open horizons, provided local artists with a visual environment different from the Ubud and Batuan, which are located in the hinterland. The playful atmosphere pervades the Sanur paintings and is not dictated by the religious iconography.[7] It is lighter and airy than those of Batuan and Ubud with sea creatures, erotic scenery, and wild animals drawn in rhythmic patterns. It is possible that these works, and those of Batuan, influenced the European artist M.C. Escher. Most early works were black and white ink wash on paper, but at the request of Neuhaus, latter works were adorned with light pastel colors often added by a small number of the artists who specialized in coloring black and white drawings, notably I Pica and I Regug, who left their Balinese initials the margins.

The Sanur school of painting is the most stylized and decorative among all modern Balinese Art. Major artists from Sanur are I Rundu, Ida Bagus Nyoman Rai, Ida [Bagus] Made Pugug, I Soekaria, I [Gusti] Made Rundu, and I Pica. I Rudin, who lived nearby in Renon, started to paint in the mid-1930s, and in the 1950s turned to drawing Balinese dancers in the manner of the drawings of Miguel Covarrubias.

Young Artist painting

The development of the Young Artist School of painting is attributed to the Dutch artist Arie Smit, a Dutch soldier who served during the 2nd world-war and decided to stay in Bali. In the early 1960s, he came across children in the village of Penestanan near Tjampuhan drawing on the sand. He encouraged these children to paint by providing them with paper and paints.[6]

Their paintings are characterized by "child-like" drawings that lacks details and bright colors drawn with oil paint on canvas. By the 1970s, it attracted around three hundred peasant painters to produce paintings for tourists. In 1971 Datuk Lim Chong Kit held an exhibition of Young Artists' work from his collection, at Alpha Gallery in Singapore entitled Peasant Painters of Bali. A version of that exhibition was held in 1983 at the National Gallery of Malaysia.

The painting by I Wayan Pugur (b. 1945) shown here, was executed when he was 13 years old and was exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1964, as part of a traveling exhibition in the United States in 1964-1965, which was also exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution. This early drawing, executed on paper, exhibits the use of bright colors and a balanced composition. The drawing space is divided into three solid-color areas: dark blue, bright yellow, and magenta showing the influence of the Wayang painting tradition. The leaves of the large tree with the snakes show the juxtaposition of complementary colors. The faces of the figures were drawn with no details, yet the snakes have eyes and long tongues.

Major artists from the Young Artist School are I Wayan Pugur, I Ketut Soki,[10] I Ngurah KK, I Nyoman Londo, I Ketut Tagen, M D Djaga, I Nyoman Cakra, Ni Ketut Gampil, I Nyoman Mundik, I Wayan Regug and many others.

Keliki miniature painting

In the 1990s, miniature paintings emerged from Keliki, a small village north of Ubud, led by a local farmer I Ketut Sana.[8] The sizes range from as small as 2 x 3 inches to as large as 10 x 15 in. I Ketut Sana learnt to paint from I Gusti Nyoman Sudara Lempad from Ubud and from I Wayan Rajin from Batuan. He combined the line drawing of Lempad and the details of the Batuan school. Every inch of the space is covered with minute details of Balinese village life and legends drawn in ink and colored with watercolor. The outcome is a marriage between the youthfulness of the Ubud school and the details of the Batuan School. The Keliki artists were proud of their patience in painting minute details of every object that occupied the drawing space.

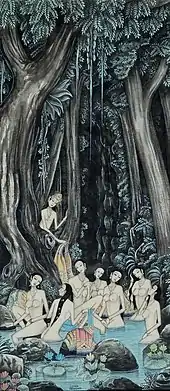

Illustrated on the left is a drawing by I Lunga (c. 1995) depicting the story of Rajapala. Rajapala is often referred to as the first Balinese voyeur or “peeping Tom.” According to the story, Rajapala catches sight of a group of celestial nymphs bathing in a pool. He approaches stealthily, and without their knowledge, steals the skirt (kamben) of the prettiest, Sulaish. As her clothing contains magical powers enabling her to fly, the nymph cannot return home. Rajapala offers to marry her. She accepts on the condition that she will return to heaven after the birth of a child. With time, she and Rajapala have a healthy young son. Years pass, and one day, Sulaish accidentally discovers her clothing hidden in the kitchen. Understanding that she has been tricked, she takes leave of her husband and son and goes back to her heavenly abode.

Major artists from the Keliki Artist School are Sang Ketut Mandera (Dolit),[8] I Ketut Sana, I Wayan Surana, I Lunga, I Wayan Nengah, I Made Ocen, Gong Juna, I Made Widi, I Wayan Lanus, I Wayan Lodra,[8] Ida Bagus Putra, Gusti Ngurah Putra Riong and many others.

Other Schools of Painting

Fingerprint painting

A Balinese of royal descent, I Gusti Ngurah Gede Pemecutan makes his paintings by fingerprints. If we use the brush technique, we can brush it off if needed, but the fingerprint technique should place every dot precisely. His fingerprint paintings have no signature but have a lot of his fingerprints. The fingerprint painting technique is regarded as part of the pointillism painting technique (with the brush).[11]

Wood carving

Like the Balinese painting, Balinese wood carving underwent a similar transformation during the 1930s and 1940s. The creative outburst that emerged during this transition period is often attributed to Western influences. In 2006, an exhibition at the Nusantara Museum, Delft, the Netherlands Leidelmeijer[12] traced the Art Deco influence on Balinese wood carving. Leidelmeijer further conjectured that the Art Deco influence continued well into the 1970s.

During the transition years, the Pitamaha Artist Guild was the prime mover not only for Balinese paintings but also for the development of modern Balinese wood carvings. I Tagelan (1902-1935) produced an elongated carving of a Balinese woman from a long piece of wood that was given by Walter Spies, who originally requested him to produce two statues.[6] This carving is in the collection of the Puri Lukisan Museum in Ubud.

Other masters of Balinese modernist woodcarving were: Ida Bagus Nyana, Tjokot (1886-1971),[2] and Ida Bagus Tilem. Ida Bagus Nyana was known for experimenting with mass in sculpture. When carving human characters, he shortened some parts of the body and lengthened others, thus bringing an eerie, surreal quality to his work. At the same time, he didn't overwork the wood and adopted simple, naive themes of daily life. He thus avoided the “baroque” trap, unlike many carvers of his day.

Tjokot gained a reputation for exploiting the expressive quality inherent in the wood. He would go into the forest to look for strangely shaped trunks and branches and, changing them as little as possible, transform them into gnarled spooks and demonic figures.[2]

Ida Bagus Tilem, the son of Nyana, furthered Nyana and Tjokot's innovations both in his work of the wood and in his choice of themes. Unlike the sculptors from the previous generation, he was daring enough to alter the proportions of the characters depicted in his carving. He allowed the natural deformations in the wood to guide the form of his carving, using gnarled logs well suited for representing twisted human bodies. He saw each deformed log or branch as a medium for expressing human feelings. Instead of depicting myths or scenes of daily life, Tilem took up “abstract” themes with philosophical or psychological content: using distorted pieces of wood that are endowed with strong expressive powers.[2] Ida Bagus Tilem, however, was not only an artist but also a teacher. He trained dozens of young sculptors from the area around the village of Mas. He taught them how to select wood for its expressive power, and how to establish dialogue between wood and Man that has become the mainstream of today's Balinese woodcarving.

Museums holding important Balinese painting collections

There are many museums throughout the world holding a significant collection of Balinese paintings.[13]

- Europe: In the Netherlands, the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam and the Ethnographic Museum in Leiden have a large number of paintings from the Wayang period (before the 1920s) and the pre-war period (1920s - 1950s). Notably, the Leiden Ethnographic Museum holds the Rudolf Bonnet and Paul Spies collection. In Switzerland, the Ethnographic Museum in Basel holds the pre-War Batuan and Sanur paintings collected by Schlager and the artist Theo Meier. In late 2010, the Ethnographic Museum in Vienna (Austria) rediscovered the pre-war Balinese paintings collected by Potjewyd in the mid-1930s.

- Asia: In Japan, the Asian Art Museum in Fukuoka holds an excellent Balinese collection after the Second World War. The National Gallery Singapore has a significant collection of pre-war and post-war Balinese paintings.

- Australia: The Australian Museum, Sydney, has a major collection of Kamasan and other traditional paintings assembled by the Anthropologist Anthony Forge. The National Gallery of Australia in Canberra holds some Balinese works.

- Indonesia: the Museum Sana Budaya in Yogyakarta and Museum Bentara Budaya in Jakarta. In Bali, pre-war Balinese drawings are at the holdings of the Bali Museum in Denpasar and the Center for Documentation of Balinese Culture in Denpasar. In addition, there are four major museums in Ubud, Bali, with significant collections: Museum Puri Lukisan, Agung Rai Museum of Art, Neka Art Museum , and Museum Rudana.

- America: Duke University Museum in Durham, American Museum of Natural History in New York, United Nations in New York.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Covarrubias, Miguel (1937). Island of Bali. Cassel.

- 1 2 3 4 Eiseman, Fred and Margaret (1988). Woodcarving of Bali. Periplus.

- ↑ Forge, Anthony (1978). "Balinese Traditional Paintings" (PDF). The Australian Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ "The Realm of Balinese Classical Art Form". Archived from the original on 2012-04-02.

- 1 2 3 Geertz, Hildred (1994). Images of Power: Balinese Paintings Made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1679-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Couteau, Jean (1999). Catalogue of the Museum Puri Lukisan. Ratna Wartha Foundation (i.e. the Museum Puri Lukisan). ISBN 979-95713-0-8.

- 1 2 3 Spanjaard, Helena (December 2007). Pioneers of Balinese Painting. KIT Publishers. ISBN 978-90-6832-447-1. Archived from the original on 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- 1 2 3 4 Agus Dermawan, Bali Bravo — a Lexicon of 200 years Balinese Traditional Painters, Bali Bangkit, 2006.

- ↑ Höhn, Klaus (1997). Reflections of Faith: The History of Painting in Batuan, 1834-1994: The Art of Bali. Published by Pictures Publishers Art Books.

- ↑ Soki, Ketut. "Pak Soki. Artist from Penestanan, the 'Village of Young Artists'". I Ketut Soki. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ↑ "I Gusti Ngurah Gede Pemecutan: Stamping a legacy with Balinese fingerprint paintings". July 12, 2012. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- ↑ Frans Leidermeijer, Art Deco beelden van Bali (1930-1970) - van souvenir tot kunstobject, Waanders, 2006, ISBN 90-400-8186-7

- ↑ Haks, Frans; Kunsthal Rotterdam (1999). Pre-war Balinese Modernists, 1928-1942. Ars et Animatio. ISBN 90-5349-297-6.

References

- Peasant Painters from the Penestanan Ubud Bali — Paintings from the Collection of Datuk Lim Chong Keat, National Art Gallery Kuala Lumpur (1983)

- Agus Dermawan, "Bali Bravo — A Lexicon of 200-years Balinese Traditional Painters," Bali Bangkit (2006)

- Anak Agung Djelantik, " Balinese Paintings," Oxford University Press (1990)

- Christopher Hill, "Survival and Change: Three Generations of Balinese Painters," Pandanus Books (2006)

- Jean Couteau, Museum Puri Lukisan Catalog, Bali, Indonesia (1999)

- Joseph Fischer, "Problems and Realities of Modern Balinese Art," in Modern Indonesian Art: Three Generations of Tradition and Change 1945-1990, Joseph Fischer, editor (1990)

- Haks, F., Ubbens J., Vickers, Adrian, Haks, Leo. and Maris, G., "Pre-War Balinese Modernists," Ars et Animatio (1999)

- Helena Spanjaard, Pioneers of Balinese Painting, KIT Publishers (2007). For USA and Canada follow this link, Stylus Publishers

- Hildred Geertz, Images of Power: Balinese Paintings Made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, University of Hawaii Press (1994)

- McGowan, Kaja; Adrian Vickers; Soemantri Widagdo; Benedict Anderson (July 2008). Ida Bagus Made — The Art of Devotion. Museum Puri Lukisan. ISBN 978-1-60585-983-5.

- Klaus D. Höhn, The Art of Bali: Reflections of Faith: the History of Painting in Batuan, 1834-1994, Pictures Publishers Art Books (1997)

- Moerdowo, "Reflections on Balinese Traditional and Modern Arts," Balai Pustaka (1983)

- Neka, Sutedja and Kam, Garrett, "The Development of Painting in Bali — Selections from the Neka Art Museum," 2nd edition, Museum Neka Dharma Seni Foundation (2000)

- Rhodius, Hans and Darling, John, "Walter Spies and Balinese Art," Terra, Zutphen (1980)

- Ruddick, Abby, "Selected Paintings form the Collection of the Agung Rai Fine Art Gallery," The Agung Rai Fine Art Gallery (1992)

- Taylor, Alison, "Living Traditions in Balinese Painting," The Agung Rai Gallery of Fine Art (1991)

- Mann, Richard I., "Classical Balinese Painting, Nyoman Gunarsa Museum", Book, Illustrated - 2006.

External links

- Kamasan, The Realm of Balinese Traditional and Classical Art-forms - A complete description of the Classic Kamasan style paintings.

- Balinese Painting and Woodcarving - Fine examples of Balinese paintings and woodcarvings

- Historic Lempad Exhibition - The world premier of Lempad drawings from the 1930s to 1940s at the Puri Lukisan Museum, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia.

- Walter Spies Painting Archived 2017-08-03 at the Wayback Machine - Paintings from Balinese and European period

- Museum Puri Lukisan - The home of the finest collection of pre-war Balinese paintings and woodcarvings in Bali

- Agung Rai Museum of Art (ARMA) - The only museum in Bali with an original work of Walter Spies

- Agung Rai Museum of Art (ARMA) at Google Cultural Institute

- Neka Museum - Works of foreign artists who lived in Bali, Arie Smit, I Gusti Njoman Lempad

- KIT - Indonesian works of art at the Tropenmuseum Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- Foreign Artists in Bali - Short biography of foreign artists who worked in Bali, including: W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, C.L Dake, P.A.J. Mooijen, Willem Dooijewaard, Rolland Strasser, John Sten, Walter Spies, Rudolf Bonnet, Miguel Covarrubias, Isaac Israel, Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Mepres, Theo Meier, Willem and Maria Hofker, Emilio Ambron, Auke Sonnega, Romuldo Locatelli, Lee Man Fong, Antonio Blanco, Arie Smit, Donald Friend

- Crossing Boundaries Exhibition Bali: A window to the 20th century Indonesian Art — an exhibition organized by Asia Society AustralAsia Center

- Bali: Art, Ritual, Performance An exhibition of Balinese art at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Keliki Painting School - A school for to learn the miniature traditional painting of Bali.

- Balinese Painting group on facebook - A group discussion for balinese art.

- Balinese Art from 1800 - 2012 - Adrian Vickers' book Balinese Art Paintings and Drawings of Bali 1800 - 2010

- Balinese Art - Australian Museum - Balinese Art - Australian Museum