For broader context, see Typeface anatomy.

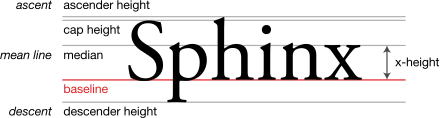

In European and West Asian typography and penmanship, the baseline is the line upon which most letters sit and below which descenders extend.[1]

In the example to the right, the letter 'p' has a descender; the other letters sit on the (red) baseline.

Most, though not all, typefaces are similar in the following ways as regards the baseline:

- capital letters sit on the baseline. The most common exceptions are the J and Q.

- Lining figures (see Arabic numerals) sit on the baseline.

- The following text figures have descenders: 3 4 5 7 9.

- The following lowercase letters have descenders: g j p q y.

- Glyphs with rounded lower and upper extents (0 3 6 8 c C G J o O Q) dip very slightly below the baseline ("overshoot") to create the optical illusion that they sit on the baseline, and rise above the x-height or capital height to create the illusion that they have the same height as flat glyphs (such as those for H x X 1 5 7). Peter Karow's Digital Typefaces suggests that typical overshoot is about 1.5%.

The vertical distance of the base lines of consecutive lines in a paragraph is also known as line height or leading, although the latter can also refer to the baseline distance minus the font size.

Northern Brahmic scripts have a characteristic hanging baseline; the letters are aligned to the top of the writing line, marked by an overbar, with diacritics extending above the baseline.

East Asian scripts have no baseline; each glyph sits in a square box, with neither ascenders nor descenders. When mixed with scripts with a low baseline, East Asian characters should be set so that the bottom of the character is between the baseline and the descender height.

See also

References