| Battle of Bean's Station | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Bean Station Hotel before it was dismantled in 1941 to make way for the TVA's Cherokee Dam.[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

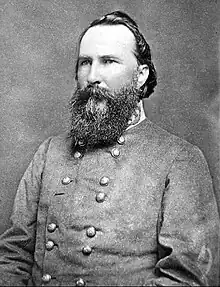

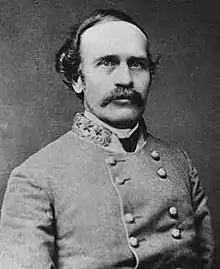

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Confederate Forces in East Tennessee | Army of the Ohio | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 12,000 Engaged: 4,200[2] | 5,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 290[2]–900[4] | 115[3]–700[4][5] | ||||||

Location within Tennessee  Battle of Bean's Station (the United States) | |||||||

The Battle of Bean's Station (December 14, 1863) was a battle fought in Grainger County, Tennessee, during the Knoxville campaign of the American Civil War. The action saw Confederate forces commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet attack Union Army cavalry led by Brigadier General James M. Shackelford. After a clash that lasted until nightfall, Longstreet's troops compelled the Federals to retreat. Two cavalry columns that were intended to envelop Shackelford's force were unable to cut off the Union cavalry, though one of the columns captured 25 Federal wagons. On December 15, Shackelford was joined by some Union infantry southwest of Bean's Station where they skirmished with the Confederates before withdrawing again.

Longstreet's troops began the Siege of Knoxville on November 19. When Major General Ambrose Burnside's garrison was relieved on December 4 by a much larger Union army led by Major General William T. Sherman, Longstreet retreated northeast to Rogersville. The pursuing Union force under Major General John Parke soon halted at Rutledge and Bean's Station. Learning that the bulk of Sherman's army left the area, Longstreet decided to assume the offensive again. He planned to surround and crush Shackelford's cavalry, but the Union cavalry resisted stubbornly, and the Confederate cavalry pincers failed to close. On December 16, Shackelford joined Parke's main Union field force at Blaine's Crossroads. Seeing that his strategy failed, Longstreet withdrew to the northeast.

Background

Strategic situation

Though it was part of the Confederacy, many of East Tennessee's inhabitants remained loyal to the Union. Political pressure was put on President Abraham Lincoln's administration to send a Federal army to occupy the region. When military men looked at the problem, they saw how difficult it would be to maintain an army over 200 mi (322 km) of poor roads. Nevertheless, Burnside was appointed commander of the Army of the Ohio with both the IX Corps and the XXIII Corps and ordered to undertake the invasion of East Tennessee from Kentucky. On June 3, 1863, the IX Corps was called away to help with the Siege of Vicksburg, which delayed Burnside's plans. During this time, the Confederate invasion of the North was defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg and the Union captured Vicksburg, securing control of the Mississippi River. On August 16, Burnside advanced with 18,000 troops from the XXIII Corps and entered East Tennessee by way of Kingston. Burnside's infantry occupied Knoxville on September 3 and received the surrender of the Confederate garrison at Cumberland Gap on September 9. Subsequently, Burnside drove the local Confederate forces northeast toward Virginia.[6]

The Union defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19–20, 1863 caused Burnside to move most of his strength southwest to defend Knoxville. Meanwhile, 6,000 men from the IX Corps arrived in East Tennessee to reinforce Burnside. On November 14, the Union forces were attacked by Longstreet's corps, which was detached from General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee near Chattanooga. After the Battle of Campbell's Station on November 16, Burnside's troops withdrew in good order within the defenses of Knoxville where they were besieged by Longstreet's Confederates. On November 25, Major General Ulysses S. Grant routed Bragg's army at the Battle of Missionary Ridge. Soon afterward, Grant sent Sherman with a large army to relieve Knoxville. At its approach, Longstreet withdrew on December 4 to the northeast. Sherman left Major General Gordon Granger and the IV Corps with Burnside and returned to Chattanooga with the remainder of his army. Burnside was relieved at his request and replaced in command of the Army of the Ohio by Major General John G. Foster[7] on December 11.[8]

Longstreet's advance

Before retreating, Longstreet held a council of war with his subordinates. It was determined not to rejoin Bragg's army, since the route through the mountains to Dalton, Georgia, was too difficult. However, Major General Lafayette McLaws recommended that Longstreet remain in East Tennessee in order to encourage the inhabitants who were pro-Confederate. On December 5, Longstreet's troops reached Blaine's Crossroads, about 18 mi (29.0 km) northeast of Knoxville, where they rendezvoused with the division of Major General Robert Ransom Jr. The Confederate force paused at Rutledge until December 8, then continued to Rogersville where it halted from December 9–14. Many of Longstreet's soldiers hoped to return to Virginia, and were disappointed to remain in Tennessee. Because the men were poorly supplied during the retreat, they plundered local farmers with a heavy hand. Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson reported that desertion was a problem in his Tennessee brigade.[9]

On September 5, Burnside ordered his cavalry to pursue Longstreet.[10] On December 7, Burnside's infantry left Knoxville under the command of Parke. Each man left his knapsack behind and only carried 60 rounds of ammunition, half of a shelter tent, and scanty provisions. Some of the artillery was left behind because of a lack of horses to pull the guns. Granger's men, exhausted by their march from Chattanooga, were left to garrison Knoxville. Shackelford's cavalrymen followed the retreating Confederates, picking up about 150 stragglers by the time they reached Bean's Station on December 9. That day, Parke's infantry halted at Rutledge, about 9 mi (14.5 km) southwest of Bean's Station. The badly provisioned Federals were unable to go any farther because Longstreet's soldiers had stripped the countryside of food. Foster arrived in Knoxville on December 11 and assumed command of the Army of the Ohio the following day.[11]

On December 10, Confederate President Jefferson Davis gave Longstreet authority over all troops in East Tennessee. Word reached Longstreet on December 12, that Sherman's army was headed back to Chattanooga. He learned that Parke was no longer pursuing his forces and the Confederates were able to obtain local food supplies. Longstreet still hoped to draw the Federals into a pitched battle, crushing them and forcing them to abandon Knoxville. Therefore, Longstreet decided to remain in East Tennessee. His immediate plan was to encircle Shackelford's forces at Bean's Station.[12] To do this, the Confederates would advance in three columns in order to catch the Union cavalrymen in a vise.[5]

Despite its name, Bean's Station was not a depot on the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad. Rather it was a convenient stopping place where a road from Cumberland Gap met the Great Warpath of the Cherokees. By 1825 a 52-room hotel was located at the site and there were about 20 houses in the area in 1863. To the north was Clinch Mountain which ran northeast to southwest. From Bean's Station, a road snaked north across Clinch Mountain before continuing to Tazewell and Cumberland Gap. Another good road ran southwest to Rutledge, Blain's Crossroads, and Knoxville.[13] Shackelford's cavalry defended a narrow valley that was bounded on the north by Clinch Mountain and on the south by Big Ridge, which was lower.[14]

Longstreet ordered Brigadier General William T. Martin to move two cavalry divisions along the south bank of the Holston River until they were west of Bean's Station, then cross the river and block the valley behind Shackelford's force. Brigadier General William E. "Grumble" Jones was directed to move his cavalry brigade along the north side of Clinch Mountain to prevent the Union troops from escaping to the north. Longstreet's column, headed by Colonel Henry L. Giltner's cavalry brigade and Johnson's two infantry brigades, would attack Bean's Station frontally.[12][15] The weather was clear and cold from December 5 to 12, but then it rained hard for a day and a half, causing the Holston River and other streams to rise and muddying the roads. Longstreet decided to carry out his planned attack in spite of the foul weather. He ordered his soldiers to cook three days rations in preparation for the forward move.[16]

On December 13, Longstreet sent Giltner's cavalry and Brigadier General Benjamin G. Humphreys' infantry brigade to within 3 mi (4.8 km) of Bean's Station, which involved a 24 mi (39 km) round-trip march in the rain. This probe confirmed the presence of Shackelford's cavalry. Several Confederates were captured in the skirmishing and interrogated; Shackelford learned that an attack was imminent. He notified Parke that Longstreet was, "in our front". He also sent out the 1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment to screen his front and set up pickets on the Morristown (south of Bean's Station) and Rogersville roads. On December 14, both Parke and Brigadier General Robert Brown Potter, commander of IX Corps, visited Shackelford at Bean's Station. Burnside's Chief Engineer, Captain Orlando Metcalfe Poe also was there to find positions near Bean's Station to fortify.[17]

The battle

December 14: infantry attack

On the morning of December 14, Longstreet's troops began their 16 mi (26 km) march to Bean's Station in the rain. Giltner assigned 100 horsemen from the 4th Kentucky Cavalry to lead the column. Following Giltner's cavalry, in order, were the infantry divisions of Johnson, McLaws, and Brigadier General Micah Jenkins.[16] Altogether, Longstreet's column was made up of about 12,000 soldiers.[14] At 2 pm, Parke, Shackelford, Potter, and other officers had lunch, after which Poe traveled north on the Tazewell road. Soon afterward, one of Shackelford's brigade commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Emery S. Bond reported that Confederates encountered his outpost 3 mi (4.8 km) northeast on the Rogersville road. Bond's troopers made a fighting withdrawal, compelling their opponents to commit part of Brigadier General Archibald Gracie's infantry brigade.[14]

Shackelford commanded about 5,000 men organized into five brigades that included both cavalry and mounted infantry regiments. One unit, the 8th Michigan Cavalry Regiment was armed with the Spencer repeating rifle. Shackelford deployed Colonel Frank Wolford's division to the south of the main road. Two of Wolford's brigades, those of Bond and Lieutenant Colonel Silas Adams, were posted on a commanding hill. Wolford's third brigade under Colonel Charles D. Pennebaker was placed to the left rear of the other two. The 45th Ohio Infantry Regiment (mounted) was held in reserve. Colonel John W. Foster's division was deployed north of the main road. Colonel Israel Garrard's brigade held the center while Colonel Horace Capron's brigade defended the left flank on a hill with a church and cemetery. Five companies of Colonel John H. Ward's 27th Kentucky Infantry Regiment (mounted) took position inside the Bean's Station hotel.[14] Union artillery unlimbered west of the hotel on both sides of the road.[18]

Gracie's Alabama brigade deployed north of the main road, while Johnson's Tennessee brigade, under Colonel John S. Fulton, lined up to the south of the road. Early in the action, Gracie was struck in the forearm by a bullet and compelled to relinquish command. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander directed Captain Osmond B. Taylor's Virginia Battery to deploy its four 12-pounder Napoleons north of the main road and Captain William W. Parker's Virginia Battery to take position south of the road. Both batteries mainly targeted the Federal artillery, but Johnson asked one section of Parker's guns to fire at the dismounted Union cavalry.[19] Parker's battery was armed with four 10-pounder Parrott rifles.[20]

When Fulton's troops charged the hill, Wolford's men responded with enough fire to force the Confederates to lie prone. However, after a few minutes, Fulton's men advanced again and caused Wolford's soldiers to waver. Shackelford ordered the 45th Ohio forward from reserve to stiffen the line. Wolford rode along his line waving his hat and the Union soldiers held their ground. Gracie's brigade moved toward the hotel but had to stop after going 0.25 mi (402 m). Led by Colonel John W. A. Sanford and the 60th Alabama Infantry Regiment, Gracie's soldiers advanced again until they were within 200 yd (183 m) of the Union defense line where they were again brought to a stand by heavy gunfire. At this time, Longstreet ordered Johnson to make an all-out push. Johnson personally encouraged Fulton's men and they drove Wolford's soldiers off the hill. Wolford's troops assumed a new position 200 yd (183 m) southwest of the hotel. As Fulton's troops moved in pursuit they were struck by enfilade fire coming from the hotel and stopped. The soldiers on Fulton's right flank fired at the hotel.[21]

The 60th Alabama was badly hit by rifle fire coming from Federals on the second and third stories of the hotel. Nevertheless, the regiment advanced again to a large stable only 50 yd (46 m) from the hotel, where they took cover. At this time, two Alabamians were killed and two wounded by friendly artillery fire that targeted the stable. Somewhat later, the 43rd and 59th Alabama Infantry Regiments in skirmish order moved forward to the right of the 60th Alabama.[22] Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw's brigade of McLaws' division arrived on the field and was directed to the right of Gracie's brigade.[5][18] At 4 pm, Kershaw formed the 8th and 15th South Carolina Infantry Regiments about 700 yd (640 m) from the northern hill. The two regiments advanced and drove Capron's brigade from the hill. Kershaw saw that by advancing another 300 yd (274 m), the two units might strike Garrard's brigade and the hotel from the rear. Meanwhile, McLaws ordered Brigadier General Goode Bryan to support Kershaw.[23]

Alexander moved some batteries from his battalion to the northern hill where there were good firing positions. However, Longstreet denied him permission to open fire for fear of hitting Kershaw's troops.[23] Longstreet ordered Jenkins to assist Johnson's division. Jenkins sent Brigadier General George T. Anderson's brigade to the extreme left flank, but darkness fell before it could accomplish anything. About 150 Federals from the 27th Kentucky still held out in the hotel, though they were under fire from three directions. The 43rd and 59th Alabama were to the north, the 60th Alabama was to the east, and Fulton's right flank was to the south.[24] Johnson ordered one section of Parker's guns moved to within 350 yd (320 m) of the hotel, and two shots were fired into the hotel before Gracie's brigade rushed forward.[25] Ward ordered the hotel evacuated before his men were trapped. Either the 8th or 9th Michigan Cavalry Regiments, lost in the dark, blundered into the Confederates closing in on the hotel and unwittingly helped the 27th Kentucky to escape. Even so, three Kentucky soldiers were captured in the cellar.[24]

Shackelford's troops got away in the darkness, though their retreat was very confused. In the chaos, four Confederates came to Shackelford's headquarters to ask where to find Gracie's brigade. Kershaw's brigade was unable to carry out its planned attack due to nightfall, though it captured enough bacon to feed its men for a day. The victorious Confederates also found abandoned saddles and other cavalry equipment. They also saw a line of campfires, but upon inspection they found no Union soldiers present. The fires were apparently lit by the Federals as a diversion.[26]

December 14: cavalry attack

Longstreet’s encircling movement was tactically sound, but it ultimately did not succeed.[18] Martin mishandled his part of the operation.[27] His two cavalry divisions advanced through Morristown, but were blocked at May's Ford by a small force of Union cavalry. At 11 pm, the defenders were forced to retreat after being shelled by two of Martin's artillery batteries. However, Martin did not try to cross the difficult ford that night, and it was early on December 15 before his two divisions reached the Holston River's north bank. As Poe and a small party of Federals rode north from Bean's Station on the afternoon of December 14, they were nearly captured by Jones' cavalrymen. Poe's party warned a wagon train's commander that Confederate horsemen were nearby and managed to reach safety at Tazewell. However, a half hour later, Jones' brigade captured 25 Federal wagons carrying sugar and coffee for the IX Corps. For unknown reasons, Jones never completed his part of the envelopment of Shackelford's force.[28]

The 117th Indiana Infantry Regiment, a 6-month unit, was repairing the road over Clinch Mountain that went north from Bean's Station to Tazewell. Its commander Colonel Thomas J. Brady heard the sounds from Jones' attack on the wagon train on the north side, as well as the racket from the fight at Bean's Station to the south. Brady sent five companies downhill to the wagon train's assistance, but the train surrendered before they arrived. They were withdrawn to stop some Confederates that Jones sent up the slope farther east. There was a brief skirmish before Jones decided to pull his men back. As evening fell, Brady realized that his regiment was isolated, and he ordered his soldiers to abandon their equipment and retreat. At 9 pm, the 117th Indiana began filing southwest along the crest of Clinch Mountain. They reached Rutledge the next day, reuniting with other Federal forces. The next morning, McLaws sent Brigadier General Benjamin G. Humphreys' brigade to round up the Union soldiers reported to be on Clinch Mountain. Except for 12 prisoners, their quarry was long gone, but the Confederates helped themselves to 400 blankets, 34 mules, 6 wagons, plus overcoats, canteens, and other gear that their opponents left behind.[29]

Losses

Johnson reported that his division suffered 222 casualties, including 60 from Fulton's brigade and 162 from Gracie's brigade.[25][note 1] Kershaw reported 62 casualties, and counting losses from other units, Earl J. Hess stated that the total Confederate loss was 290 men.[30] Shackelford's official losses were 115 killed, wounded, and missing. See table below.[31] The Federals also lost 12 men captured from the 117th Indiana and an unknown number from the wagon train.[29] J. Rickard stated that the Union lost 700 casualties while Confederate losses numbered 900.[4] The National Park Service listed 115 Union and 222 Confederate casualties.[32] Longstreet had 12,000 men available but only 4,200 soldiers came into action. Shackelford's Union force counted about 5,000 men.[33] Longstreet wrote, "we were looking for large capture more than fight". Johnson admitted that the Federals fought "persistently and gallantly". Alexander wrote that the action, "had been bloody for its duration and our side had the worst of it".[34]

Aftermath

Parke ordered his infantry to march toward Bean's Station and Brigadier General Milo S. Hascall's infantry division (XXIII Corps) met Shackelford's retreating mounted force at 2:30 am on December 15. The combined force moved to a defensive position 0.5 mi (805 m) east of Godwin's House and the men began building a breastwork of fence rails across the valley. The position was 3 mi (4.8 km) west of Bean's Station and 5 mi (8.0 km) east of Rutledge. Shackelford and Hascall requested Parke to send forward Potter's IX Corps. Parke did so, and also ordered Granger's IV Corps at Knoxville to join them. Jenkins' division, now leading Longstreet's column, approached the new Union position at 9 am on December 15. After conducting a reconnaissance, Jenkins ordered Anderson to skirmish while Colonel John Bratton's brigade tried to turn the Federals' northern flank and Brigadier General Henry L. Benning's brigade turned the south flank. Both flanking attempts failed.[35]

The brigades of Brigadier Generals Evander Law and Jerome B. Robertson finally reached the Godwin's House position at 2:30 pm. Earlier, these units guarded Longstreet's wagon train, but they were ordered forward on December 13. Longstreet criticized Law for their tardy appearance. McLaws remained at Bean's Station, citing that he needed to feed his soldiers. By late afternoon, Martin marched from May's Ford to the ridge on the Union right flank. After a strenuous effort, Martin's artillerists hauled their guns up the slope and opened an enfilading fire on the Federals. Galled by this barrage, the Union force abandoned its position at dusk. Unfortunately for the Confederates, there was no communication between Martin and Jenkins, so their efforts were not coordinated.[36] Historian Douglas Southall Freeman remarked that, "Pursuit was attempted but futile, Longstreet maintained, because Evander Law was slow and Lafayette McLaws was loath to move before bread was issued the hungry men".[27]

While December 15 had seen mild and dry weather, the following day turned cold. The retreating Union soldiers passed through Rutledge before dawn and reached a position 2 mi (3.2 km) east of Blain's Crossroads by early afternoon on December 16. Parke's forces included the troops of Shackelford, Hascall, and Potter. Granger's troops arrived later in the afternoon as the troops constructed a breastwork of fence rails. Longstreet's men reached the new Federal defenses and that night saw heavy rain. On December 17, there was an artillery duel and skirmishing all day, as Parke's men dug trenches. A cavalry reinforcement led by Brigadier General Washington Elliott reached Parke.[37] Elliott brought 2,500 cavalry and 6 guns from the Army of the Cumberland.[38]

Longstreet claimed that his opponents were "greatly demoralized and in some confusion". Disappointed that he failed to score a significant victory, he lashed out at his subordinates.[37] Longstreet realized that the Federals had entrenched themselves beyond eviction.[39] That night, Longstreet ordered a withdrawal to the east amid bitterly cold weather.[30] Longstreet soon placed his troops into winter quarters at Russellville.[39] Hess asserted that, "Bean's Station proved to be barren of strategic value for the Confederates".[40] On December 17, Longstreet removed McLaws from the command of his division and later filed charges for a court-martial. Longstreet and McLaws had been friends, and this dispute permanently soured their relationship. Ultimately McLaws was acquitted. Longstreet also preferred charges against Law and Robertson.[41]

Union casualties

All infantry regiments listed in the table were serving as mounted infantry.[31]

| Unit | Officers killed | Enlisted killed | Officers wounded | Enlisted wounded | Officers captured | Enlisted captured | Aggregate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14th Illinois Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| 112th Illinois Infantry Regiment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 5th Indiana Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 11 |

| 6th Indiana Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 7 |

| 65th Indiana Infantry Regiment | 0 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 12 | 29 |

| 1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 11th Kentucky Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| 27th Kentucky Infantry Regiment | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 16 |

| 8th Michigan Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9th Michigan Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| 2nd Ohio Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7th Ohio Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| 45th Ohio Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Totals | 0 | 16 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 47 | 115 |

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ The killed, wounded, and missing total for Fulton's brigade was 54, but curiously, Bushrod Johnson listed 60 "aggregate" casualties. For Gracie's brigade, the total killed, wounded, and missing was 151, but 162 "aggregate" losses were listed. The difference between "total" and "aggregate" is inexplicable.

- Citations

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 292–293.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 262.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 261.

- 1 2 3 Rickard 2000.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1999, p. 39.

- ↑ Cox 1882, pp. 9–13.

- ↑ Cox 1882, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, p. 302.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 191–194.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 197.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 200–202.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 207.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 207–208.

- 1 2 3 4 Hess 2013, p. 210.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 208.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 208–210.

- 1 2 3 King 2018.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 253.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, p. 535.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 213.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 214.

- 1 2 Official Records 1890, p. 536.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 214–215.

- 1 2 Freeman 1944, p. 299.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 215.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 216.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 Official Records 1890, p. 293.

- ↑ NPS 2022.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 217.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 218.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 199.

- 1 2 Smith 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 220.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 233–236.

References

- "Battle Detail: Bean's Station". National Park Service. 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- Boatner, Mark M. (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York: David McKay Co. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Cox, Jacob D. (1882). "Atlanta". New York, N.Y.: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- Freeman, Douglas S. (1944). Lee's Lieutenants-A Study in Command. Vol. 3. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hess, Earl J. (2013). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-995-8.

- King, Spurgeon (2018). "Battle of Bean's Station". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Rickard, J (2000). "Battle of Bean's Station, 14 December 1863". HistoryOfWar.org. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Smith, David (1999). Campaign to Nowhere: The Results of General Longstreet's Move into Upper East Tennessee. Strawberry Plains Press.

- "The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. XXXI Part 1". Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1890. p. 293. Retrieved October 14, 2020.