| Siege of Knoxville | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

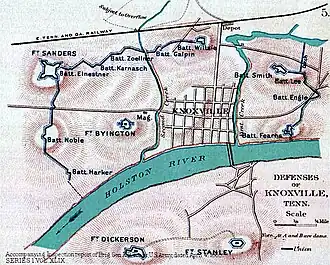

Map shows the Knoxville defenses. Mabry's Hill and Fort Hill are off map to the right. Fort Higley is off map, below and to the left of Fort Dickerson. Sevierville Heights are off map to the right of Fort Stanley.[note 1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Ohio | Longstreet's Corps | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000[1] | 14,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 693[1] | 1,296[2] | ||||||

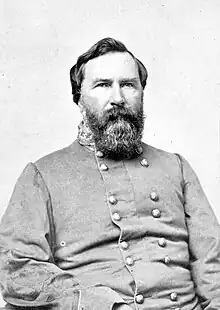

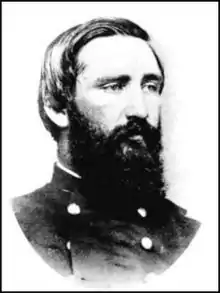

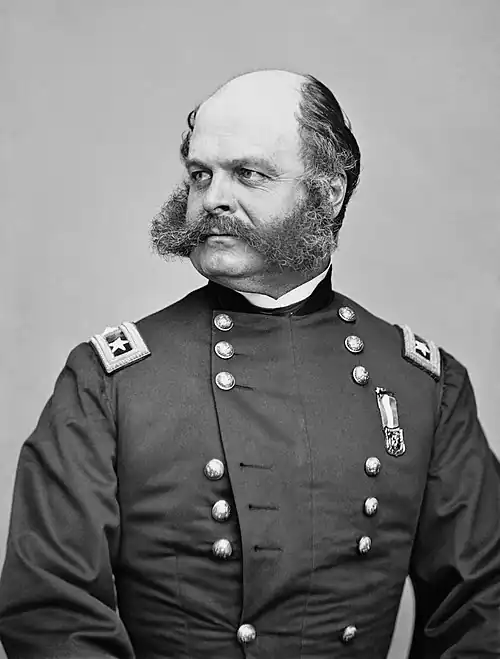

The siege of Knoxville (November 19 – December 4, 1863) saw Lieutenant General James Longstreet's Confederate forces besiege the Union garrison of Knoxville, Tennessee, led by Major General Ambrose Burnside. When Major General William T. Sherman approached Knoxville with an overwhelming Union force, Longstreet ended the siege on December 4 and withdrew northeast. The siege was part of the Knoxville campaign of the American Civil War.

In August and September 1863, Burnside's Army of Ohio carried out a nearly bloodless invasion of East Tennessee, an area that included a substantial pro-Union population. Burnside's occupying force was thrown on the defensive when Longstreet's corps and Major General Joseph Wheeler's cavalry launched a counter-invasion from the southwest in November. Longstreet missed his chance to smash the Union forces in the field when Burnside conducted a successful fighting withdrawal to Knoxville. When Longstreet hesitated to attack, the Union soldiers built fortifications to make Knoxville's strong natural defenses even more powerful.

Longstreet's forces lacked sufficient strength to completely surround Knoxville. Therefore, Burnside's Union garrison avoided starvation by bringing food into the city from the south bank of the Tennessee River. On November 29, a major Confederate assault was repulsed with heavy losses in the Battle of Fort Sanders. Aside from day-to-day skirmishing, there were two other significant actions, the first on November 18 west of the city and the second on November 25 at Armstrong's Hill on the south bank. After the siege ended, Longstreet's troops lingered in East Tennessee until April 1864, but were unable to capture Knoxville.

Background

Union occupation

Burnside, commanding the Union Army of the Ohio,[3] mounted the Union invasion of East Tennessee in late August 1863, with two infantry divisions and one large cavalry division from XXIII Corps soldiers stationed in Kentucky. Burnside's offensive was mostly unopposed and Federal troops occupied Knoxville on September 1. Many of the people of East Tennessee were pro-Union and welcomed the Union troops. By mid-September, Burnside's troops had seized control over a large part of East Tennessee.[4] When Bragg's Army of Tennessee defeated the Union Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19–20, 1863 the strategic situation dramatically changed. After his victory, Bragg effectively blockaded the Army of the Cumberland within Chattanooga.[5]

On September 20, two divisions of IX Corps joined Burnside, and on October 3, Brigadier General Orlando B. Willcox with 3,000 six-month Indiana soldiers arrived at Cumberland Gap.[6] The Army of the Ohio's strength returns for October 1863 reported the following troops present for duty: 6,352 officers and enlisted men in IX Corps, 7,912 infantry and artillery and 7,458 cavalry in XXIII Corps, and 4,391 troops in the Left Wing.[7] Brigadier General Robert B. Potter commanded IX Corps, Brigadier General Mahlon D. Manson directed XXIII Corps,[8] Brigadier General James M. Shackelford led the cavalry, and Willcox commanded the Left Wing.[9]

Major General Robert Ransom Jr. with 5,800 Confederate infantry plus two cavalry brigades under Brigadier General William E. "Grumble" Jones and Colonel H. L. Giltner lurked to the northeast.[10] The Confederate department commander Major General Samuel Jones doubted whether his 8,000 troops were strong enough to seriously disrupt the Union occupation.[11] On October 17, Bragg ordered an infantry division under Major General Carter L. Stevenson and two cavalry brigades under Colonels George Gibbs Dibrell and J. J. Morrison to menace the Union area of control. On October 20, Dibrell and Morrison defeated a Union cavalry brigade under Colonel Frank Wolford in the Battle of Philadelphia. After this reverse, Burnside abandoned Loudon and fell back behind the Tennessee and Little Tennessee Rivers.[12]

Subsequently, Burnside massed the 6,000 men from IX Corps and 3,000 soldiers from Brigadier General Julius White's XXIII Corps infantry division in the area near Lenoir's Station. The remaining XXIII Corps infantry division under Brigadier General Milo Smith Hascall defended Knoxville, Brigadier General William P. Sanders' cavalry division observed the area around Maryville, Willcox held Bull's Gap, and two infantry regiments and 300 cavalry garrisoned Cumberland Gap.[13] In addition, two Union cavalry brigades cooperated with Willcox's force.[14] Major General Ulysses S. Grant was anxious whether Burnside could hold Knoxville.[15]

Longstreet's advance

On November 4, Bragg ordered Longstreet to detach his two divisions from the Army of Tennessee and recapture Knoxville. Bragg believed Longstreet botched the Battle of Wauhatchie on October 28, in which the Confederates proved unable to cut the Federals' newly established Cracker Line. Bragg also wished to send away a general whom he found to be troublesome. Longstreet wanted to be reinforced to 20,000 men for the campaign, but Bragg said no and recalled both Stevenson's and Benjamin F. Cheatham's infantry divisions that opposed Burnside. However, Bragg loaned him Major General Joseph Wheeler and most of his army's mounted force. Longstreet tried to obtain accurate maps of East Tennessee but was only able to get inferior ones. The old locomotives proved unable to efficiently shift Longstreet's two divisions north at the same time that Stevenson's and Cheatham's divisions moved south, so the railroad transfer took until November 13 to complete. Longstreet discovered that Stevenson's troops had eaten most of the countryside's food supplies and that his own wagon train was hardly adequate to mount a campaign. Longstreet's command totaled 10,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 35 guns.[16]

The Confederates built a pontoon bridge at Hough's Ferry on the Tennessee River; this was a short distance west of Loudon.[17] The division of Brigadier General Micah Jenkins was first to cross the pontoon bridge to the north bank on November 14.[18] Major General Lafayette McLaws' division crossed the next day. By the evening of November 15, Burnside's forces were holding Lenoir's Station, confronted by Jenkins' division to the north with McLaws' division farther north. Longstreet hoped to cut off Burnside's troops from Knoxville, but did not have a good understanding of the area.[19] Earlier, Longstreet authorized Wheeler and most of the cavalry to attempt to seize Knoxville from the south. Wheeler defeated Sanders' Union cavalry in several encounters during November 14–15, pressing them back to the outskirts of Knoxville. However, Wheeler was ultimately thwarted when his troopers ran into Knoxville's infantry defenders on the south bank of the Tennessee River. On November 16, Longstreet recalled Wheeler's cavalry to the north bank, but by that time it was too late to use the horsemen to trap Burnside's forces.[20]

On the north bank of the Tennessee were Longstreet's 12,000 Confederates, including one brigade of Wheeler's cavalry. Opposing them were 9,000 Union troops under Burnside. Longstreet's advance on November 14–15 was so rapid that one of White's two Union brigades was left behind at Kingston where it remained until Knoxville was relieved.[21] Burnside began evacuating Lenoir's Station during the night of November 15. Marching on muddy roads caused by a recent heavy rain, the Federals reached Campbell's Station ahead of Longstreet's pursuit. On November 16, Longstreet failed to crush Burnside in the Battle of Campbell's Station. The Federal rearguard made three separate stands that morning before joining Burnside's main force astride the Kingston Pike in the early afternoon. When the Confederates began turning Burnside's left flank, the Federals fell back to a fifth position. Supported by their artillery, the Union infantry conducted a well-executed fighting withdrawal before marching through the night. The first infantry did not reach Knoxville until 4:00 am on November 17.[22]

Siege

Sanders' delaying action

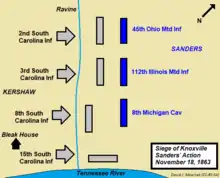

Burnside's directed his chief engineer, Captain Orlando Metcalfe Poe to assign each brigade a position in the defense line. As the Union soldiers arrived at Knoxville, Poe gave them their orders. As soon as the soldiers were able, they began building defenses according to Poe's plans. The troops were assisted in the construction by pro-Union volunteers, by drafted Confederate sympathizers who proved to be unenthusiastic, and by Black workers who were "particularly efficient" at the work. Burnside also ordered Sanders to bring his cavalry division to the north bank to oppose Longstreet. Sanders posted four mounted regiments behind Tank Creek (now known as Fourth Creek) to the west of Knoxville. By 9:20 am on November 17, Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw's brigade of McLaws' division began pressing against Sanders' defense line. After a skirmish, Sanders withdrew 1 mi (1.6 km) east and took up a new position around noon. McLaws sent a regiment to outflank this line from the north, but before it could get into position, Sanders' horsemen pulled back again.[23]

Sanders fell back to a hilltop position behind a small ravine west of Third Creek and 750 yd (686 m) east of a home belonging to Robert H. Armstrong,[24] known as Bleak House.[25] At this point, the Tennessee River was immediately on Sanders' left flank and a branch of Third Creek protected his right flank. McLaws deployed his division with Kershaw's brigade facing Sanders and Brigadier General Goode Bryan's brigade in the second line. To Kershaw's left on a ridge was Brigadier General Benjamin G. Humphreys' brigade with Colonel Solon Z. Ruff's brigade in second line. McLaws did not attempt to advance farther that day; he waited while Jenkins' division arrived and extended Longstreet's line to McLaws' left. By evening on November 17, Jenkins' division was positioned across the road to Clinton while Colonel John R. Hart's Georgia cavalry brigade was farther east, blocking the road leading to Tazewell.[24]

Sanders posted about 600 Union soldiers with the 45th Ohio Mounted Infantry on his right, 112th Illinois Mounted Infantry in the center, and 8th Michigan Cavalry on the left. The 8th Michigan's men were armed with the Spencer repeating rifle. Two cedar trees marked the center of the line on the otherwise bare hilltop. The Union troops dismounted and every fifth man held the horses of four other men. Along the front line, the Union soldiers built a breastwork of fence rails about 3 ft (0.9 m) high and the same width at the base. Colonel Charles D. Pennebaker's Union cavalry brigade of two regiments faced Humphreys' and Ruff's brigades farther north. East of Third Creek, Colonel James W. Reilly's infantry brigade formed a battle line. Burnside requested Sanders to hold his advanced position until noon on November 18. That would give time for soldiers and workers to put Knoxville in a state of defense.[26]

On November 18, Longstreet planned to drive Sanders off his hill and probe Burnside's defenses, but a heavy fog delayed Confederate operations until 10:00 am. Confederate skirmishers then attacked Sanders' line but were driven off. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander unlimbered four Confederate guns near Bleak House and took Sanders' troops under fire, causing losses in the 45th Ohio. At 2:00 pm, Kershaw's skirmishers mounted a second attack, approaching within 25 yd (22.9 m) of the Federal line before being driven off.[27] During the fighting, several Confederate snipers took position in an upper story of Bleak House and opened a harassing fire on Sanders' troops. Sanders asked First Lieutenant Samuel Nicoll Benjamin, commander of 2nd U.S. Artillery, Battery E if his 20-pounder Parrott rifles could suppress the sharpshooters. Though the range was extreme at 2,500 yd (2,286 m), a projectile from one of Benjamin's guns burst in the room where the snipers were. Poe remarked, "During the whole war, I saw no prettier shot."[28]

At 3:00 pm, the final attack commenced when Captain George V. Moody's Louisiana battery, Madison Light Artillery, opened fire from the ridge to the north. It was soon joined by the 12-pounder Napoleons of Captain Osmond B. Taylor's Virginia Battery near Bleak House which blasted gaps in the rail breastwork. The 2nd South Carolina and 3rd South Carolina Infantry Regiments assaulted the Union right and center while the 15th South Carolina supported by the 8th South Carolina attacked the Union left. After a bitter struggle, the Federals retreated. Colonel James D. Nance of the 3rd South Carolina wrote that, "this was the most desperate encounter in which my command was ever engaged." McLaws reported that his division suffered 140 casualties, while Union losses were 200–300. The 112th Illinois reported suffering 94 casualties. The commander of the 15th South Carolina, Major William M. Gist, was killed. Sanders was fatally wounded, possibly by one of the snipers in Bleak House,[29] and died at 11:00 am on November 19.[30] Sanders had been promoted brigadier general only a month before, on October 18, 1863.[31] Fort Loudon, which was originally built by the Confederates, was renamed Fort Sanders in honor of the slain Union general on November 24.[30]

Knoxville defenses

.jpg.webp)

In 1863, the city of Knoxville was located entirely on the north bank of the Tennessee River. Poe's defenses were laid out on a ridge that was at least 100 ft (30 m) higher than the surrounding terrain that trended past the north side of the city. The railroad line ran roughly east-west just north of the ridge with the depot directly north of the city. The East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad went west from the depot; the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad went east. First Creek ran south into the Tennessee on the east side of the city; Second Creek ran south into the river on the west side of Knoxville. Third Creek was farther west, near where Sanders' fight took place.[32]

.jpg.webp)

Brigadier General Edward Ferrero's IX Corps division held the Union defenses on the west side of the city from the river to Fort Sanders and west to Second Creek. Colonel John F. Hartranft's smaller IX Corps division defended the line north of Knoxville between First and Second Creeks. Colonel Marshall W. Chapin's brigade of Brigadier General Julius White's division held the defenses from First Creek to Mabry's Hill. Colonel William A. Hoskins' provisional XXIII Corps brigade and pro-Union Tennessee volunteers defended the line from Mabry's Hill to the river east of the city. Hascall's division was disposed with Colonel Daniel Cameron's brigade defending the south side of the Tennessee River and Colonel James W. Reilly's brigade forming Burnside's reserve.[33] Brigadier General James M. Shackelford also assigned cavalry units to assist Cameron's infantry south of the river.[34] These included Colonel Frank Wolford's brigade which remained on the south bank throughout the siege.[35]

On November 19, Longstreet moved his troops to oppose the Union defenses of Knoxville. Technically, Longstreet's operation was not a siege because the Confederates were unable to completely surround the city. When the IX Corps arrived from Kentucky, it brought 2,000 hogs and 600 cattle. Another 800 hogs reached the city before the city was cut off.[36] During the siege, the pro-Union farmers of the French Broad River valley east of Knoxville provided the garrison with 10,000 bushels of corn, 6,000 bushels of wheat, 1,500 hogs, 1,000 cattle, and additional foodstuffs. This was in addition to what Union foragers gathered south of the Tennessee River. Longstreet did not have enough troops to interrupt these supplies, but he also mistakenly believed a faulty map that placed the French Broad River in the wrong place. Pro-Confederate civilians pointed out the error, but the general apparently doubted their loyalty to the Southern cause.[37]

Except for Fort Sanders, all the Union forts surrounding Knoxville received their official names on December 11, 1863, after the end of the siege. All the forts were named after Union officers killed during the campaign. On the north side of the river, Battery Noble was defended by two 3-inch Ordnance rifles from Captain Jacob Roemer's Battery L, 2nd New York Artillery. Fort Byington was located on College Hill, while Battery Zoellner was east of Fort Sanders and Battery Galpin even farther east. Fort Comstock was on Summit Hill overlooking the depot and was armed by four 10-pounder Parrott rifles from Lieutenant Erskine Gittings' 3rd U.S. Artillery, Batteries L and M. Farther east were Battery Wiltsie and Battery Billingsley; the latter had three 3-inch rifles from Captain John von Sehlen's 15th Indiana Battery. Fort Huntington Smith was a major fortification sited on Temperance Hill and it included several 3.8-inch James rifles from Captain Joseph A. Sims' 24th Indiana Battery and Captain Edward C. Henshaw's Illinois Battery. Farther east, Battery Clifton Lee and Battery Stearman were each armed with two 6-pounder guns from Henshaw's Battery.[38]

Completing the north side defenses, Fort Hill on Mabry's Hill included six 12-pounder Napoleons from Captain Joseph C. Shields' 19th Ohio Battery and two 3-inch rifles from Captain Hubbard T. Thomas' 26th (Wilder) Indiana Battery. Battery Fearns was sited on Flint Hill east of Knoxville and was armed with two 12-pounder howitzers. South of the river, Fort Stanley was a major earthwork. Farther west was Fort Dickerson, and to the southwest of Dickerson was Fort Higley.[39] During the siege, the soldiers of Cameron's brigade extended trenches east from Fort Stanley to include Sevierville Heights.[35]

Fort Sanders was constructed as a bastioned earthwork, with its northern and southern sides 125 yd (114 m) long, its western side 95 yd (87 m) long, and its eastern side open. Its ditch was 12 ft (3.7 m) wide and 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) deep. The fort was armed with four 20-pounder Parrott rifles from Benjamin's battery, six 12-pounder Napoleons from Captain William W. Buckley's Battery D, 1st Rhode Island Artillery, and two 3-inch rifles from Roemer's battery. The infantry garrison consisted of 120 men from the 79th New York Infantry, 75 men from the 29th Massachusetts Infantry, 80 men from the 20th Michigan Infantry, and 60 men from the 2nd Michigan Infantry. In addition, 40 men from the 2nd Michigan manned a firing step in front of the northwest bastion; when pressed, they were intended to retreat from this position and enter the fort at the southeast corner. More than twice as many men as the garrison were probably able to deliver fire on any attackers of Fort Sanders.[40] Counting the artillery crews, there were about 440 men manning the fort.[41]

Kingston

Longstreet was anxious about the line of communication between his forces and Bragg's army near Chattanooga. He believed that the Union garrison of Kingston might pose a threat. Colonel H. B. Lyon and 320 Confederate cavalrymen erroneously reported that there were only two Union cavalry regiments in Kingston. Based on Lyon's report, Longstreet authorized Wheeler to take most of his two divisions to Kingston and wipe out its garrison. Leaving behind five cavalry regiments to screen the sector from Jenkins' left flank to the river east of Knoxville, Wheeler began his march on the morning of November 23. Wheeler's horsemen arrived near Kingston early on November 24, worn out from the march and lack of food. They were opposed by Colonel Robert K. Byrd's forces which included Colonel Samuel R. Mott's Federal infantry brigade (White's division), four regiments strong, plus the 1st Tennessee Mounted Infantry[42] and Captain Andrew M. Wood's Elgin Illinois Battery.[43] In the Battle of Kingston, Wheeler's cavalry was unable to dislodge the strongly-posted Union garrison and withdrew at noon. Wheeler returned to Bragg's army and left Brigadier General William T. Martin in command of his cavalry corps. Martin and the cavalry soon rejoined Longstreet's forces.[44]

On the night of November 23, Jenkins advanced his skirmish line to the railroad north of Knoxville. This action prompted the Union soldiers to set fire to the buildings near the railroad depot, where a quantity of old ammunition was stored. The resulting pyrotechnical display entertained the inhabitants of Knoxville. On the morning of November 24, Hartranft ordered his troops to push back the Confederates, which was successfully done at the cost of 22 Union casualties. At the same time, Ferrero ordered a sortie by the 2nd Michigan Infantry Regiment against a position from which Confederates were firing at Fort Sanders. The position was briefly taken, but the 2nd Michigan suffered heavy losses and was compelled to retreat.[45]

Armstrong Hill

From early in the siege, the Confederates tried to find the most vulnerable point in Knoxville's defenses. Alexander believed that Fort Sanders was the weak spot and arranged his artillery to take the fort under crossfire. Meanwhile, Longstreet hoped to conduct operations on the south bank and on November 20 sent Bryan's brigade across the Tennessee River to Cherokee Heights. On November 22, Longstreet contemplated making an assault on Fort Sanders, but called it off. Instead, he sent the four 10-pounder Parrott rifles of William W. Parker's Virginia Battery across to Cherokee Heights. This would allow Fort Sanders to be shelled from the south, but only at the extreme range of 2,300 yd (2,103 m). On November 24, Longstreet replaced Bryan's brigade with the brigades of Brigadier Generals Evander M. Law and Jerome B. Robertson, both from Jenkins' division. Bragg also decided to send infantry reinforcements and his chief engineer, Brigadier General Danville Leadbetter to Knoxville, so Longstreet decided to put off any immediate plans to attack Fort Sanders.[46]

Armstrong Hill was a wooded height that stood 400 ft (122 m) above the Tennessee River. It was east of Cherokee Heights and west of the hill where Fort Higley would soon be built. On November 25, Longstreet ordered Law to use both brigades to make a reconnaissance-in-force. Opposing Law's and Robertson's Confederates were, from right to left, five companies of the 24th Kentucky, eight companies of the 65th Illinois, and seven companies of the 103rd Ohio Infantry Regiments. The 103rd Ohio had just moved into position, was taken by surprise, and driven back. However, it quickly rallied, drove off Law's skirmishers, and regained the top of the hill. After holding the hilltop for 90 minutes, Cameron decided to launch his own advance.[47]

The 24th Kentucky and 65th Illinois advanced across the valley and gained a foothold in the woods at the base of Cherokee Heights, but the 103rd Ohio was held up by a log cabin that the Confederates used as a strongpoint. With help from the other two regiments, the Ohioans finally captured the log house. Later in the day, Wolford's cavalry joined the Union forces. The 24th Kentucky advanced partly up Cherokee Heights but was recalled by Cameron and all three infantry units re-established their original picket lines and withdrew to Armstrong Hill. Law reported 85 casualties and Robertson reported 31 casualties. Union losses were about 50 casualties. The outcome was remarkable because the Confederates were veterans, while Cameron's troops had limited combat experience. On November 27, Cameron's men were put to work building Fort Higley and entrenching the Sevierville Heights.[48]

Fort Sanders

The Confederates planned to wreck the vital pontoon bridge that connected Knoxville with the south bank, but nothing came of this effort. Nevertheless, Poe stretched a cable across the river upstream to block any attempt to break the bridge. Meanwhile, the Federals continued to improve their defensive fortifications. Old telegraph wire was found and run between tree stumps in a narrow belt in front of Fort Sanders.[49] The 2,625-strong division of Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson reached Longstreet on November 26–27. Johnson brought two brigades under Brigadier General Archibald Gracie III and Colonel John S. Fulton, but no artillery. Meanwhile, Leadbetter wanted to attack Mabry's Hill, but a reconnaissance on November 27 discovered that its Union defenses were far too strong to give any hope of success. Later that day, Longstreet watched through his binoculars as a Union soldier walked from Fort Sanders to his sentry post. It seemed to him that the ditch was only waist deep. What Longstreet could not have known was that the sentry used a plank to cross the deep ditch. Yet it convinced Longstreet that the ditch around the fort was insignificant.[50]

Longstreet wanted to assault Fort Sanders at dawn on November 28, but the operation was rescheduled until 2:00 pm when a rainstorm struck the area. Then, McLaws convinced Longstreet to postpone the attack until the morning of November 29 so that his skirmish line could be advanced close to the fort. Meanwhile, the cavalry brigades of "Grumble" Jones and Giltner from Ransom's division arrived near Knoxville. These troops were sent to the north when it was discovered that Willcox's Union forces were advancing from Cumberland Gap. Rumors began circulating that Grant defeated Bragg near Chattanooga, but this made Longstreet more determined to attack. McLaws' assault on Fort Sanders was made in two side-by-side columns. The left column was made up of Ruff's brigade, while the right column was composed of units from both Humphreys' and Bryan's brigades. Gracie's and Fulton's brigades were positioned so that they could form a second wave of attack. At the same time, Brigadier General George T. Anderson's brigade from Jenkins' division was ordered to attack the Union trenches east of Fort Sanders. If the assault captured the fort, Law was supposed to attack the south bank defenses.[51]

At 10:00 pm, McLaws advanced his skirmish lines to within 80 to 120 yd (73 to 110 m) of Fort Sanders. The operation was successful, but it alerted the Federals that the fort was about to be assaulted. McLaws' two assault columns of about 2,400 men formed about 250 yd (229 m) to the northwest of the fort.[52] The infantry assault began at 6:20 am after a 20 minute artillery bombardment. The front ranks were knocked over when they reached the wire entanglement, but got up again and surged forward. When the Confederates reached the ditch, it was a rude surprise. The Union parapet loomed 18 ft (5.5 m) above the bottom of the deep ditch. To reach the parapet, the attackers had to climb a slippery clay slope of about 70° while braving intense fire. During the attack, Union officers ordered their soldiers into the fort to assist the garrison. Benjamin lit the fuses of his battery's artillery shells and threw them into the ditch among the crowded Confederates. Union infantry also poured flanking fire into the ditch from the east.[53] Anderson's attack was bungled; it was made in the wrong direction and sustained only 37 casualties.[54]

The assault failed and cost the Confederates 129 killed, 458 wounded, and 226 missing, for a total of 813 casualties. Historian Earl J. Hess stated that Union casualties were only about 20 men inside the fort and 30 men outside.[55] According to Jacob Dolson Cox, there were 43 Union casualties.[56] Ruff was killed and so was his successor, Colonel Henry P. Thomas of the 16th Georgia Infantry. Colonel Kennon McElroy of the 13th Mississippi Infantry was also killed. Colonel Edward Ball of the 53rd Georgia Infantry, Lieutenant Colonel John Fiser of the 17th Mississippi Infantry, and Major Joseph Hamilton of Phillip's Georgia Legion were wounded.[57] Perhaps 30 minutes after the assault failed, Longstreet received official news that Grant badly defeated Bragg at the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863. Burnside allowed a truce so that the Confederates could recover their dead and wounded.[58] Some defenders belonging to the IX Corps regarded the battle as revenge for the Federal defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg.[59]

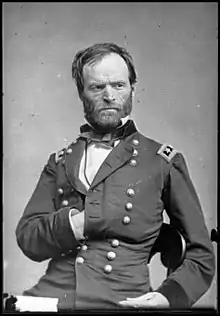

Relief

After the debacle at Fort Sanders, Longstreet decided to besiege Burnside for as long as possible. He believed this would force Grant to relieve Knoxville and hopefully divert some Union forces away from Bragg's beaten army.[60] When the Union forces chasing Bragg's army were repulsed at the Battle of Ringgold Gap on November 27, Grant called off the pursuit. He assigned Major General William Tecumseh Sherman to command a large force designed to relieve Knoxville. Sherman was given command of Major General Gordon Granger's IV Corps, Major General Oliver Otis Howard's XI Corps, Major General Francis Preston Blair Jr.'s XV Corps, Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis's division of XIV Corps, and Colonel Eli Long's cavalry brigade. Sherman soon started his troops marching toward Knoxville and they reached Charleston, Tennessee, on the Hiwassee River on November 30. Because the situation was considered urgent, Sherman's force marched without its artillery and wagon trains.[61] Granger's corps included the divisions of Major General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood. Howard's corps consisted of the divisions of Major General Carl Schurz and Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr. Blair's corps comprised the divisions of Brigadier Generals Morgan Lewis Smith and Hugh Boyle Ewing. Sherman's infantry numbered approximately 30,000 men.[62]

Grant arranged for a message announcing Sherman's approach to fall into Confederate hands. A second copy was sent via Byrd at Kingston and got through to Burnside. While Sherman's main column, consisting of Blair, Howard, and Davis crossed the Hiwassee at Charleston, Granger's troops crossed at Kincannon's Ford to the west. Since the railroad bridge at Charleston was wrecked and the Confederates destroyed all the rolling stock between there and Knoxville, Sherman's army was compelled to live off the country. On December 3, Howard reached Loudon to find the railroad bridge wrecked. Sherman shifted Granger's corps from his left to his right wing. Granger, Blair, and Davis crossed the swollen Little Tennessee River at Morganton via an improvised bridge, while Howard crossed at Davis' Ford to the west on a bridge built from wagons captured at Loudon. Long's cavalry brigade rode ahead and reached Knoxville before dawn on December 4.[63]

Meanwhile, Willcox moved south and repulsed an attack by Martin's cavalry at the Battle of Walker's Ford on December 2. Though it was a Union tactical victory, Willcox's force was too weak to advance any farther.[64] While Sherman's 30,000 advanced on the east bank of the Tennessee River, Brigadier General James G. Spears and three Tennessee Union regiments at Sale Creek advanced on the west bank. On December 3, Spears reached Kingston where he incorporated Byrd's and Mott's troops into his command. The Federals bumped into a Confederate cavalry brigade which soon retreated and joined Longstreet's command. Spears' brigade occupied Loudon while Mott's brigade continued moving toward Knoxville, reaching there on December 9.[65]

After acquiring the message announcing Sherman's approach, Longstreet determined to retreat northeast toward Virginia. The mountainous route to join Bragg's army near Dalton, Georgia was regarded too difficult to travel. Longstreet refused Wheeler's request to return his cavalry corps to Bragg's army; he needed Martin's cavalry to form a rearguard. Law's and Robertson's brigades were moved to the north bank on December 3. That day, the Confederate wagon train started moving away from the city. On the evening of December 4, Longstreet's troops began to march away from Knoxville. Moody's battery of 24-pounder howitzers was the last artillery in action. It was a difficult march; it rained, and then the temperature dropped below freezing, cutting the feet of soldiers without shoes. By December 9, Longstreet's troops reached Rogersville. The Confederates left behind men who were too wounded or sick to march, and numbers of stragglers were also captured.[66]

Aftermath

By the evening of December 5, Howard's troops reached Louisville (Tennessee), while the soldiers of Granger, Blair, and Davis arrived at Maryville. After receiving news that Longstreet's forces retreated, Sherman ordered only Granger's IV Corps to continue marching to Knoxville. Sherman, Granger, and Howard reached Knoxville on December 6 where they were treated to dinner at Burnside's headquarters. Sherman was annoyed because he had been led to believe that the garrison was starving. Satisfied that Knoxville was safely in Union hands, Sherman ordered Howard's XI Corps, Blair's XV Corps, and Davis' division to immediately march back to Chattanooga, which they reached December 16–18. Since the Federal forces remaining in East Tennessee needed cavalry reinforcements, Brigadier General Washington Lafayette Elliott's 2,500 cavalry and six guns were ordered to march from Alexandria, Tennessee. Elliott's force reached Kingston on December 11, bringing a wagon train with fresh clothing for Burnside's troops, who were still wearing their tattered summer uniforms.[67]

Granger's divisions stayed in Knoxville to reinforce Burnside's forces;[56] the IV Corps rejoined the Army of the Cumberland for the Atlanta campaign in spring 1864. The XXIII Corps also served in that campaign.[68] Beginning on March 17–23, 1864, the IX Corps was transferred to Annapolis, Maryland, in the Eastern Theater and heavily reinforced.[69] On December 7, Burnside organized a pursuit using soldiers from the IX and XXIII Corps led by Major General John Parke; this effort reached Rutledge and Bean's Station before halting. Major General John G. Foster replaced Burnside as commander of the Army of the Ohio on December 11, but he was injured by falling off his horse and relieved on February 9, 1864.[70]

The Knoxville siege cost the Federals 92 killed, 394 wounded, and 207 missing, for a total of 693 casualties. See table below. The Confederates counted 198 killed, 850 wounded, and 248 missing, for a total of 1,296 casualties. McLaws' division lost 782, while Jenkins' division lost 514 men. The Confederate cavalry never made a casualty report.[71] Longstreet still hoped to defeat the Union forces in the field and then compel them to abandon Knoxville. Finding that most of Sherman's troops had left the area, he planned to envelop Shackelford's cavalry at Bean's Station.[72] The result was the indecisive Battle of Bean's Station on December 14.[73]

Longstreet mounted more forays into the Union-held areas of East Tennessee. On December 29, 1863, the Battle of Mossy Creek was a cavalry fight. On January 17, 1864, the Battle of Dandridge resulted in the Federals pulling back toward Knoxville. Longstreet's forces advanced as far as Strawberry Plains by early February, but finally withdrew to winter quarters at Russellville.[74] Longstreet's corps was recalled to fight in the Eastern Theater on April 11.[75] Throughout the campaign, both sides suffered from lack of supplies. The Federals in East Tennessee were at the end of a long railroad supply line extending from Nashville south to Chattanooga and then northeast to Knoxville.[76] However, the worst of Knoxville's supply problems were resolved by March 1.[69] One Confederate veteran of the campaign recalled that, "all the boys used to say that all East Tennessee lacked of being hell was a roof over it".[77]

Casualties

Union losses

Click show to display table.

| Corps | Division | Brigade | Unit | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IX Corps Brigadier General Robert Brown Potter |

Headquarters | Not brigaded | 6th Indiana Cavalry Regiment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 1st Division Brigadier General Edward Ferrero |

1st Brigade Colonel David Morrison |

36th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| 8th Michigan Infantry Regiment | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |||

| 79th New York Infantry Regiment | 4 | 10 | 0 | 14 | |||

| 45th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |||

| 1st Brigade Total | 4 | 19 | 6 | 29 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Colonel Benjamin C. Christ |

29th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | ||

| 27th Michigan Infantry Regiment | 6 | 12 | 20 | 38 | |||

| 46th New York Infantry Regiment | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | |||

| 50th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment | 2 | 5 | 2 | 9 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Total | 15 | 25 | 24 | 64 | |||

| 3rd Brigade Colonel William Humphrey |

2nd Michigan Infantry Regiment | 10 | 67 | 16 | 93 | ||

| 17th Michigan Infantry Regiment | 3 | 10 | 18 | 31 | |||

| 20th Michigan Infantry Regiment | 2 | 16 | 12 | 30 | |||

| 100th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment | 3 | 9 | 0 | 12 | |||

| 3rd Brigade Total | 18 | 102 | 46 | 166 | |||

| 1st Division Artillery |

34th Battery New York Light Artillery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Battery D, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 1st Division Total | 37 | 148 | 76 | 261 | |||

| 2nd Division Colonel John F. Hartranft |

1st Brigade Colonel Joshua K. Siegfried |

2nd Maryland Infantry Regiment | 1 | 7 | 26 | 34 | |

| 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment | 1 | 13 | 1 | 15 | |||

| 48th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment | 3 | 7 | 5 | 15 | |||

| 1st Brigade Total | 5 | 27 | 32 | 64 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Lt. Colonel Edwin Schall |

35th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 11th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 51st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Total | 4 | 7 | 3 | 14 | |||

| 2nd Division Artillery[note 2] |

3rd U.S. Artillery, Batteries L and M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2nd Division Total | 9 | 34 | 35 | 78 | |||

| Unattached | Artillery | 2nd U.S. Artillery, Battery E | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Summary | Corps Total | 47 | 184 | 112 | 343 | ||

| XXIII Corps Brigadier General Mahlon Manson |

2nd Division Brigadier General Julius White[note 3] |

2nd Brigade Colonel Marshal W. Chapin |

107th Illinois Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13th Kentucky Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 23rd Michigan Infantry Regiment | 0 | 8 | 2 | 10 | |||

| 111th Ohio Infantry Regiment | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Henshaw's Battery Illinois Light Artillery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2nd Division Total | 0 | 13 | 6 | 19[note 4] | |||

| 3rd Division Brigadier General Milo S. Hascall |

1st Brigade Colonel James W. Reilly |

44th Ohio Infantry Regiment | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |

| 100th Ohio Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 104th Ohio Infantry Regiment | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 | |||

| Battery D, 1st Ohio Light Artillery | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 1st Brigade Total | 2 | 15 | 7 | 24 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Colonel Daniel Cameron |

65th Illinois Infantry Regiment | 3 | 20 | 0 | 23 | ||

| 24th Kentucky Infantry Regiment | 4 | 55 | 0 | 59 | |||

| 103rd Ohio Infantry Regiment | 2 | 22 | 2 | 26 | |||

| Wilder Indiana Battery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Total | 9 | 97 | 2 | 108 | |||

| 3rd Division Total | 11 | 112 | 9 | 132 | |||

| Unattached | Provisional Brigade Colonel William A. Hoskins[note 5] |

12th Kentucky Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8th Tennessee Infantry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Reserve Artillery | Captain Andrew J. Konkle | 24th Battery Indiana Light Artillery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 19th Ohio Battery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Summary | Corps Total | 11 | 125 | 15 | 151 | ||

| Cavalry Corps Brigadier General James M. Shackelford |

1st Division Brigadier General William P. Sanders (mw) Colonel Frank Wolford |

1st Brigade Colonel Frank Wolford Lt. Colonel Silas Adams |

1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| 11th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 12th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment | 3 | 5 | 6 | 14 | |||

| 1st Brigade Total | 5 | 9 | 10 | 24 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Lt. Colonel Emery S. Bond |

112th Illinois Infantry Regiment (mounted) | 18 | 38 | 12 | 68 | ||

| 8th Michigan Cavalry Regiment | 3 | 14 | 28 | 45 | |||

| 45th Ohio Infantry Regiment (mounted) | 4 | 11 | 23 | 39 | |||

| 15th Battery Indiana Light Artillery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2nd Brigade Total | 25 | 63 | 64 | 152 | |||

| 3rd Brigade Colonel Charles D. Pennebaker |

11th Kentucky Infantry Regiment (mounted) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 27th Kentucky Infantry Regiment (mounted) | 4 | 10 | 1 | 15 | |||

| 3rd Brigade Total | 4 | 12 | 1 | 17 | |||

| 1st Division Total | 34 | 85[note 6] | 75 | 194 | |||

| 2nd Division | 1st Brigade | 2nd Ohio Cavalry Regiment | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Summary | Corps Total | 34 | 85 | 80 | 199 | ||

| Army of the Ohio Major General Ambrose Burnside |

Summary | Army Total | 92 | 384 | 207 | 693 | |

Confederate losses

Click show to display table.

| Division | Brigade | Date | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hood's Division Brigadier General Micah Jenkins |

Colonel John Bratton | Nov. 14–Dec. 4 | 22 | 109 | 5 | 136 |

| Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning | Nov. 14–Dec. 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |

| Brig. Gen. Jerome B. Robertson | Nov. 25 | 8 | 17 | 6 | 31 | |

| Brig. Gen. Jerome B. Robertson | Nov. 29 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law | Nov. 25 | 14 | 64 | 7 | 85 | |

| Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law | Nov. 29 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | |

| Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson | Nov. 17–18 | 3 | 57 | 0 | 60 | |

| Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson | Nov. 29 | 33 | 129 | 25 | 187 | |

| Hood's Division Total | - | 83 | 387 | 44 | 514 | |

| McLaws Division Major General Lafayette McLaws |

Colonel Solon Z. Ruff (k) | Nov. 29 | 48 | 121 | 81 | 250 |

| Brig. Gen. Goode Bryan | Nov. 29 | 27 | 121 | 64 | 212 | |

| Brig. Gen. Benjamin G. Humphreys | not reported | 0 | 18 | 0 | 18 | |

| Brig. Gen. Benjamin G. Humphreys | Nov. 29 | 21 | 87 | 56 | 164 | |

| Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw | Nov. 17–18 | 19 | 116 | 3 | 138 | |

| McLaw's Division Total | - | 115 | 463 | 204 | 782 | |

| Grand Total | - | 198 | 850 | 248 | 1,296 | |

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Civil War era maps show the Holston River flowing past Knoxville, while modern maps call it the Tennessee River.

- ↑ The Official Records does not list this artillery unit. It is listed in Hess (p. 250).

- ↑ The 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, XXIII Corps garrisoned Kingston as noted in Hess (pp. 259–260).

- ↑ Casualties include 2 members of 2nd Division staff captured.

- ↑ This brigade was not listed in the Official Records (OR). The 8th Tennessee was listed in the OR under 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division with no losses. 12th Kentucky was not listed in the OR. Hoskins' brigade is listed in Hess (p. 251).

- ↑ The wounded total included Sanders wounded (mortally).

- Citations

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 249.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 250.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 751.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 11–16.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 19.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, p. 811.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, pp. 812–813.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, pp. 815–816.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 175.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 30.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 186.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 30–35.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 53–74.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 77–80.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 83–86.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 738.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 87–90.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 92.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, p. 720.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 96.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 96–99.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 105.

- 1 2 Hess 2013, p. 131.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 95.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 265–267.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 267.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 742–743.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 137.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 115–117.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 260.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 125–127.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 134–137.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 138–140.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 140–143.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 144–148.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 151–162.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 170–171.

- 1 2 Cox 1882, p. 14.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 167–169.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 174.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 171.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 255–260.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 179–185.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 186–189.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 198.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 191–195.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 197–199.

- ↑ Cox 1882, p. 18.

- 1 2 Cox 1882, p. 17.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, p. 302.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 206.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 207.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 261.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 224–226.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 239.

- ↑ Hess 2013, pp. 226–228.

- ↑ Hess 2013, p. 241.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, pp. 290–292.

- ↑ Official Records 1890, p. 475.

References

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 3. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-571-X.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York: David McKay Company. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Cox, Jacob D. (1882). "Atlanta". New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- Hess, Earl J. (2013). The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-995-8.

- Official Records (1890). "A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: Volume XXXI, Part I". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved March 3, 2022.