| Battle of Brienne | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Campaign of France of the Sixth Coalition | |||||||

Napoleon was nearly taken by the Cossacks after the battle, but was saved by French general Gaspard Gourgaud. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 36,000[1] | 28,000–30,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000[1]–4,000 killed, wounded, or captured | ||||||

Location within France | |||||||

The Battle of Brienne (29 January 1814) saw an Imperial French army led by Emperor Napoleon attack Prussian and Russian forces commanded by Prussian Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. After heavy fighting that went on into the night, the French seized the château, nearly capturing Blücher. However, the French were unable to dislodge the Russians from the town of Brienne-le-Château. Napoleon himself, making his first appearance on a battlefield in 1814, was also nearly captured. Very early the next morning, Blücher's troops quietly abandoned the town and retreated to the south, conceding the field to the French.

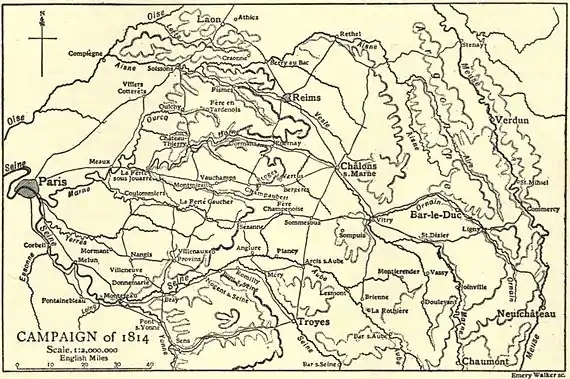

In late December 1813, two Allied armies initially numbering 300,000 men smashed through France's weak defenses and moved west. By late January, Napoleon personally took the field to lead his armies. The French emperor hoped to cripple Blücher's army before it could combine with the main Allied army under Austrian field marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg. Napoleon's gamble failed and Blücher escaped to join Schwarzenberg. Three days later, the two Allied armies combined their 120,000 men and attacked Napoleon in the Battle of La Rothière.

Prelude

Plans

In November 1813, the 70,000 French survivors of the disastrous German Campaign of 1813 crossed to the west bank of the Rhine River. Emperor Napoleon left 100,000 French soldiers in German garrisons, trapped by enemy blockading forces and hostile populations. All of Napoleon's German allies switched sides and joined the Sixth Coalition. To the south, Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult's 60,000 men and Marshal Louis Gabriel Suchet's 37,000 defended the Spanish border. Napoleon's step-son Eugène de Beauharnais with 50,000 troops defended the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy against the Austrian Empire. There were numerous French garrisons in Belgium, the Netherlands and eastern France, while 15,000 soldiers were isolated in Mainz.[3]

Czar Alexander I of Russia and King Frederick William III of Prussia wished to dethrone Napoleon, but Emperor Francis I of Austria was not anxious to overthrow his son-in-law. Francis also feared that weakening France would strengthen his rivals, Russia and Prussia. Prince Schwarzenberg followed his emperor's wait-and-see policy while Blücher burned to crush Napoleon at the earliest opportunity. Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, the crown prince of Sweden and a former French marshal, led a third Allied army. He secretly wished to replace Napoleon as the leader of France and was not inclined to invade his former homeland. The Allied leaders met at Frankfurt-am-Main to work out a plan to fight Napoleon.[4]

In the Allied plan that emerged, Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow with one of Bernadotte's corps would advance into the Netherlands and be joined there by a British corps under Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch. Blücher would cross the middle Rhine with 100,000 troops and occupy Napoleon's attention. Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg with 200,000 men would cross the upper Rhine near Basel and move toward Langres, falling on the French right flank.[5]

To oppose this vast array, Napoleon deployed Marshal Claude Perrin Victor with 10,000 troops on the upper Rhine, Marshal Auguste de Marmont with 13,000 and Horace Sebastiani with 4,500 on the middle Rhine and Marshal Jacques MacDonald with 11,500 on the lower Rhine. Holland and Belgium were held by 15,000 troops led by Nicolas Joseph Maison.[6] In reserve were the Old Guard under Marshal Édouard Mortier and two newly-formed Young Guard divisions under Marshal Michel Ney. Well to the south at Lyon, Marshal Pierre Augereau was directed to form a new army.[5]

Operations

On 22 December 1813, elements of Schwarzenberg's army crossed the upper Rhine and moved into France and Switzerland. Blücher crossed the middle Rhine on 29 December.[5] Napoleon's cordon defense quickly collapsed in the face of the two Allied armies. Victor soon abandoned Nancy and on 13 January 1814 Marmont retreated to Metz. By 17 January, Marmont, Ney and Victor withdrew behind the Meuse River. Blücher's army advanced 75 miles (121 km) in nine days and got across the Meuse on 22 January. Schwarzenberg reached Langres on 17 January where the cautious Austrian halted for a few days, convinced that Napoleon was about to attack him with 80,000 troops. When Schwarzenberg moved forward again, Mortier's Imperial Guard slowed his advance by carrying out skillful rearguard actions.[7] The First Battle of Bar-sur-Aube was fought on 24 January between Mortier's guardsmen and two of Schwarzenberg's corps.[8]

.jpg.webp)

At first, Napoleon grossly underestimated Allied numbers, crediting Schwarzenberg with 50,000 troops and Blücher with 30,000.[9] By the end of January, he formed a more realistic estimate and resolved to prevent the armies of Blücher and Schwarzenberg from joining.[10] In fact, the combined Allied armies would number 120,000 soldiers for the Battle of La Rothière on 1 February.[11] On that date, the two Coalition armies brought 85,000 men and 200 guns into action against Napoleon, who could only oppose them with 45,100 soldiers and 128 guns.[12]

Leaving his brother Joseph Bonaparte in charge of the capital, Napoleon departed from Paris and reached Châlons-sur-Marne on 26 January 1814. Near Châlons were the following forces. Victor led 14,747 men from the II Corps and Édouard Jean Baptiste Milhaud's V Cavalry Corps. Marmont headed 12,051 troops from the VI Corps and Jean-Pierre Doumerc's I Cavalry Corps. Ney directed 14,505 soldiers in three Young Guard infantry divisions under Claude Marie Meunier, Pierre Decouz and Henri Rottembourg and a Guard cavalry division under Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes. MacDonald and Sebastiani were approaching from the north with about 10,000 men but were too distant to be available. Mortier with 20,000 soldiers, including 12,000 Imperial Guards, retreated west to Troyes after his clash with Schwarzenberg's army.[13]

Napoleon directed that his presence at the front should be kept a secret. He issued four days' rations to his army and marched it from Châlons toward Saint-Dizier, where he believed Blücher was located with about 25,000 soldiers and 40 guns. When his army reached Saint-Dizier, he found that his adversary had marched southwest to Brienne-le-Château.[14] In a clash at Saint-Dizier on 27 January 1814, Milhaud's 2,100 cavalrymen drove back 1,500 Russians of Sergey Nikolaevich Lanskoy's 2nd Hussar Division.[8] At Brienne, Blücher would be near parts of Schwarzenberg's army and Napoleon hoped to drive the Prussian field marshal's forces into the Aube River before he could be reinforced.[14] Napoleon was familiar with Brienne; he had entered the Royal School of Brienne at the age of nine on 23 April 1779 and studied there for five and a half years.[15]

On 28 January, Napoleon advanced toward Brienne in three columns. Étienne Maurice Gérard's right column marched south from Vitry-le-François and included the infantry divisions of Étienne Pierre Sylvestre Ricard (of VI Corps) and Georges Joseph Dufour plus Cyrille Simon Picquet's cavalry. The center column was made up of the Imperial Guard and marched southwest from Saint-Dizier through Montier-en-Der. The left column, consisting of Victor and Milhaud, marched south to Wassy before turning west to join the center column at Montier-en-Der. Marmont was left with Joseph Lagrange's infantry division and the I Cavalry Corps near Bar-le-Duc to hold off Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg's Prussian I Corps. Napoleon sent messages to Mortier at Troyes, Étienne Tardif de Pommeroux de Bordesoulle at Arcis-sur-Aube and Pierre David de Colbert-Chabanais at Nogent-sur-Seine to cooperate with his plan. Russian Cossacks captured all three couriers and delivered their dispatches to Blücher. By the morning of 29 January, the Prussian field marshal was aware that Napoleon had gotten between him and Yorck and was approaching him from the northeast with 30,000–40,000 soldiers.[16]

The roads were in poor condition because of a thaw, but Napoleon's soldiers managed to slog through the mud to reach Montier-en-Der and Wassy by nightfall on 28 January. Blücher was in Brienne with Zakhar Dmitrievich Olsufiev's infantry corps while Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken's Russian army corps was farther west at Lesmont. The Allied VI Corps under Peter Wittgenstein was approaching Joinville but its cavalry under Peter Petrovich Pahlen reached Brienne. Schwarzenberg's headquarters was located at Chaumont. The Allied V Corps under Karl Philipp von Wrede was between Chaumont and Saint-Dizier.[17] The Allied III Corps under Ignaz Gyulai and the IV Corps under Crownprince Frederick William of Württemberg were near Bar-sur-Aube. The Allied I Corps under Hieronymus Karl Graf von Colloredo-Mansfeld was well to the south at Châtillon-sur-Seine and the Reserve under Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly was marching from Langres to Chaumont.[18]

Battle

Warned just in time of the impending French attack, Blücher recalled Sacken from Lesmont to Brienne.[19] The Prussian field marshal had Olsufiev's 6,000 infantry, Pahlen's 3,000 cavalry and Lanskoy's 1,600 hussars on hand until Sacken arrived. Olsufiev's command was part of Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron's Russian army corps. Blücher posted Olsufiev in Brienne, Pahlen in the plain to the northeast and Lanskoy near the Bois d'Ajou (Ajou Woods).[18] The 9th Light Cavalry Division under Hippolyte Piré at the point of the French advance met three Cossack regiments under Nikolay Grigoryevich Scherbatov at Maizières-lès-Brienne.[20] Scherbatov also directed the 4th and 34th Jäger Regiments which were detached from the Russian 4th Division in the Allied VI Corps.[21] Piré was soon joined by the remainder of the V Cavalry Corps under the overall command of Emmanuel de Grouchy. The French horsemen pressed back Scherbatov and Pahlen after some skirmishing.[20] Lefebvre-Desnouettes was wounded during the cavalry action.[21]

By 3:00 pm Pahlen retreated through Brienne and reformed his horsemen on the Russian right flank. The French pursuit by the divisions of Samuel-François Lhéritier and André Briche stopped when it encountered three battalions of the 4th and 34th Jägers deployed in square formation. Sacken's troops began arriving at Brienne at this time and he sent his cavalry under Ilarion Vasilievich Vasilshikov to the right flank. Napoleon called a halt until 3:30 pm when Guillaume Philibert Duhesme's II Corps infantry division reached the field. Then the French emperor ordered a general attack.[21] For an hour the soldiers of Duhesme and Olsufiev fought to a stalemate. Between 4:00 and 5:00 pm Decouz's division of Ney's corps reached the battlefield and was put in on Duhesme's right flank.[22] At first Decouz's men were successful in forcing their way deeper into the town. However, Ney called a halt when trouble developed elsewhere on the field.[23]

Noticing that Duhesme's division was not supported by cavalry, Blücher hurled 40 cavalry squadrons under Pahlen and Vasilshikov at the French left flank. The Russian horsemen routed Duhesme's division and captured eight artillery pieces.[22] In the confusion, a group of Cossacks nearly captured Napoleon, but right afterward the unruffled French emperor rallied his shaken soldiers and led them back into action.[19] Nightfall prevented a worse disaster to Duhesme, which came about because the French cavalry was all deployed on the right flank. By this time, Sacken's troops were all on the field but his wagon train was still lumbering past Brienne.[24] Blücher and his chief of staff, August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, thinking that the day's fighting was ended, went to the château. They were nearly made prisoners when some of Victor's infantry led by Louis Huguet-Chateau slipped up to the château by an unguarded road and seized the place.[25] This coup was carried out by 400 soldiers of the 37th and 56th Line Infantry Regiments. Huguet-Chateau's men also captured four guns but lost them to a Russian counterattack.[23]

Napoleon ordered the divisions of Decouz and Meunier, supported by Lefebvre-Desnouettes' cavalry, to storm Brienne. The assault was completely unsuccessful; Decouz was mortally wounded and one of his brigadiers, Rear Admiral Pierre Baste, was killed outright.[23] Another brigadier, Jean-Jacques Germain Pelet-Clozeau took temporary command of Decouz's division.[26] To keep Sacken's trains from capture, Blücher ordered Sacken to clear the French from Brienne and Olsufiev to retake the château. After bitter fighting, Sacken drove the French from most of the town, but Olsufiev failed to recapture the château.[25] Finally, Grouchy sent Lhéritier's horsemen into the town but this gallant effort was futile. At midnight, Blücher ordered Olsufiev's troops to retreat and two hours later gave Sacken instructions to withdraw. The Russian cavalry held their positions until morning.[23] The French did not initially notice the Russian withdrawal and finally occupied Brienne at 4:00 am.[25]

Result

Historian Francis Loraine Petre stated that both sides suffered about 3,000 casualties. He called the action "scarcely a tactical victory for Napoleon" and noted that the French were unable to keep Blücher from joining Schwarzenberg.[25] David G. Chandler reported that the French lost 3,000 and the Allies 4,000 casualties,[19] but that the battle was "inconclusive".[27] Digby Smith asserted that Napoleon had 36,000 troops while the Allies had 28,000. The French lost 3,500 casualties and 11 guns and the Allies sustained 3,000 casualties. François Louis Forestier, commanding Victor's 2nd Division, lost his life.[2] Forestier died of his wounds on 5 February.[28] Decouz succumbed to his wounds on 18 February.[29] George Nafziger wrote that the French lost eight guns[22] but found the Russian claim to capturing three additional guns doubtful.[21] Nafziger gave combined casualties as 6,000 without specifying how many were lost on each side.[23]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bodart 1908, p. 470.

- 1 2 Smith 1998, p. 491.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 947.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1966, pp. 948–949.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, pp. 950–952.

- 1 2 Smith 1998, p. 490.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 13.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 14.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 493.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 30.

- ↑ Petre 1994, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 Chandler 1966, p. 958.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 6.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 19.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 20.

- 1 2 Petre 1994, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1966, p. 959.

- 1 2 Nafziger 2015, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 Nafziger 2015, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Nafziger 2015, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nafziger 2015, p. 96.

- ↑ Petre 1994, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Petre 1994, p. 23.

- ↑ Horward 1973, p. 511.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 960.

- ↑ Broughton 2006.

- ↑ Broughton 2001.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905). Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- Broughton, Tony (2006). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789–1815: Fabre to Fyons". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Broughton, Tony (2001). "French Infantry Regiments and the Colonels who Led Them: 1791–1815: Pierre Decouz". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

- Horward, Donald D. (1973). The French Campaign in Portugal 1810–1811: An Account by Jean Jacques Pelet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0658-7.

- Nafziger, George (2015). The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1994) [1914]. Napoleon at Bay. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 1-85367-163-0.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

Further reading

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2002). The Napoleonic Wars: The Fall of the French Empire 1813–1815. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-431-0.

- Skaarhoj, Kasper (2017). "History of the Brienner Quartier". Munich, Germany.

External links

- Description of the battle

Media related to Battle of Brienne at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Brienne at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Sehested |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Brienne |

Succeeded by Battle of La Rothière |