| Battle of Höchst | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Palatinate phase of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

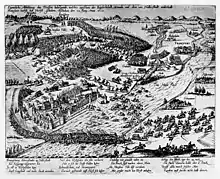

Battle near Höchst, engraving by Merian. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17,000 | 26,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 | 100 | ||||||

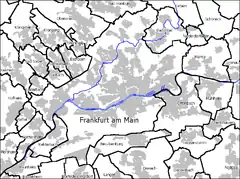

Höchst Location within Frankfurt am Main  Höchst Höchst (Hesse)  Höchst Höchst (Germany) | |||||||

The Battle of Höchst (20 June 1622) was fought between a Catholic League army led by Johan Tzerclaes, Count of Tilly and a Protestant army commanded by Christian the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, close to the town of Höchst, today a suburb of the city of Frankfurt am Main. The result was a one-sided Catholic League victory. The action occurred during the Thirty Years' War.

Background

In April 1622, Tilly had lost the Battle of Mingolsheim to Ernst von Mansfeld. In early May, however, Tilly won a decisive engagement with Georg Friedrich, Margrave of Baden-Durlach at the Battle of Wimpfen, which dispersed or killed approximately 3/4 of Georg Friederich's army, leaving only Christian of Brunswick and Ernst von Mansfeld to command in the coming battle. Meanwhile, even though Tilly had lost the army of Gonzalo de Córdoba, who had left, Tilly was more than compensated by the troops of General Tommaso Caracciolo and the count of Anholt, Johann Jakob.

Christian wanted to use the situation for a crucial strike against the Catholic League. With 12,000 infantrymen, nearly 5,000 cavalrymen, and three guns he moved from Westphalia along the Weser River shoreline, and through Hesse towards the Main River to unite his troops with armies of Mansfeld and Baden-Durlach, at Darmstadt.[1] Continuing their mission of blocking a rendezvous between Mansfeld and Christian of Brunswick, the Catholic forces reached the river at Höchst on 20 June to find Christian's army already crossing the river.

Battle

On 15 June, Christian reached the territory of the Archbishopric of Mainz at Oberursel. He sent Colonel Dodo zu Innhausen und Knyphausen with an advance guard of 1,500 men against Höchst to take the town in a coup de main and to safeguard the Main crossing point. However, the Höchst municipal troops successfully defended the town against Knyphausen's initial assault. On the 16th Knyphausen's troops finally stormed and plundered Höchst.

Two days later the Protestants started building a pontoon bridge across the Main. Meanwhile, Christian moved with his troops towards Höchst and destroyed the villages of Oberusel, Eschborn, and Sulzbach. At the same time the Catholic troops approached in forced marches from Würzburg with 20,000 infantrymen, 6,000 cavalrymen, and 18 guns. On 19 June, they arrived at the Nidda River between Nied and Sossenheim late at night.[2]

When the bridge was completed in the morning of 20 June, Christian's baggage started to cross the river. Tilly planned to force Christian's troops back to the Höchst walls and the Main, isolating the two thousand troops in Sossenheim. Hence, Christian ordered his troops to withdraw over the pontoon bridge towards Kelsterbach, but under the Catholic artillery fire the withdrawal turned into a headlong flight. The bridge broke after only 3,000 men had crossed and many of Christian's soldiers and horses drowned in the Main.[3]

By the time Höchst castle was captured at around 10 p.m., Christian had already lost a third of his army and was forced to retreat. Mansfeld lost an additional 2,000 troops acting as rearguard at Mannheim. Christian's entire baggage train and guns became Catholic loot. While the League troops lost only 100 soldiers, nearly 2,000 of Christian's soldiers died. However, Christian succeeded in escaping with 3,000 cavalrymen, 8,000 infantrymen, and his war chest, eventually uniting with Mansfeld's army. More recent investigations, however, showed that Christian had lost most of his booty.[4]

Aftermath

Tilly claimed a strategic victory because his army had far fewer losses, despite the fact that Christian of Brunswick had achieved his operational goal of uniting his army with Mansfeld's. As a result of the battle, however, his troops were severely demoralised and had also lost most of their equipment, making them more of a liability than a reinforcement.[4]

Höchst was the decisive battle of the 1622 campaign and signalled the end for "Winter King" Frederick V. Shortly after the battle, the combined Protestant forces, now numbering 26,000 strong, positioned themselves on the western bank of the Rhine and ceased to resist the invasion of the Palatinate. Frederick cancelled their contract and they were then hired by the Dutch Republic to lift the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom.[5] On their way there, they were intercepted by Córdoba's troops in the Battle of Fleurus on 29 August, but despite heavy losses, they managed to escape and reach the siege.

Heidelberg came under siege and despite an 11-week resistance, fell on 15 September. With this news, the token English forces under Sir Horace Vere evacuated Mannheim, which fell on 2 November, and moved to the fortress of Frankenthal, which served as a final outpost for Protestant resistance in this area. It fell the following year. Duke Maximillian now controlled half of the Lower Palatinate and installed Heinrich von Metternich as governor.[6]

Illustrations of the battle

A contemporary pamphlet about the battle (1625). |

The Swiss engraver Merian depicted the battle and the bridging of the Main in an engraving. Another contemporary engraving of an unknown artist shows the battle in a large panorama. Neither of these artists had been an eye witness of the event.

References

- ↑ Schäfer, Rudolf (1986). Chronik von Höchst am Main (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Waldemar Kramer.

- ↑ Vollert, Adalbert (1980). Sossenheim. Geschichte eines Frankfurter Stadtteils (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Sparkasse.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter H. (2009-07-30). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141937809.

- 1 2 Pfenninger, Markus (2022). 1622 - The Battle of Höchst. Tredition. ISBN 978-3-347-59083-0.

- ↑ Abelin, Johann Philipp (1662) [1635]. Merian, Matthäus (ed.). Theatrum Europaeum (in German). Vol. 1: 1617–1629. Frankfurt am Main: Workshop of Matthäus Merian. pp. 630–633.

- ↑ Maier, Unterpfalz, pp. 36–37, 70–96.