| Battle of Nördlingen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Thirty Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Nördlingen by Jan van den Hoecke | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

33,000[2][lower-alpha 1] 20,000 infantry 13,000 cavalry 50 guns |

25,700[2] 16,000 infantry 9,700 cavalry 68 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,500 killed or wounded[2] |

8,000[4]–12,000[5] killed or wounded 4,000 captured[4][5] | ||||||

The Battle of Nördlingen[6] took place on 6 September 1634 during the Thirty Years' War. A combined Imperial-Spanish force inflicted a crushing defeat on the Swedish-German army.

By 1634, the Swedes and their German allies occupied much of southern Germany. This allowed them to block the Spanish Road, an overland supply route running from Italy to Flanders, used by the Spanish to support their war against the Dutch Republic. Seeking to re-open this, a Spanish army under Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand linked up with an Imperial force led by Ferdinand of Hungary near the town of Nördlingen, which was held by a Swedish garrison.

A Swedish-German army commanded by Gustav Horn and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar marched to its relief but they significantly underestimated the number and calibre of the Imperial-Spanish troops facing them. On 6 September, Horn launched a series of assaults against earthworks constructed on the hills to the south of Nördlingen, all of which were repulsed. Superior numbers meant the Spanish-Imperial commanders could continually reinforce their positions and Horn eventually began to retreat. As they did so, they were outflanked by Imperial cavalry and the Protestant army collapsed.

Defeat had far-reaching territorial and strategic consequences; the Swedes withdrew from Bavaria and under the terms of the Peace of Prague in May 1635, their German allies made peace with Emperor Ferdinand II. France, which had previously restricted itself to funding the Swedes and Dutch, formally became an ally and entered the war as an active belligerent.

Background

Swedish intervention in the Thirty Years' War began in June 1630 when nearly 18,000 troops under Gustavus Adolphus landed in the Duchy of Pomerania. Provided with subsidies as part of a French policy of opposition to the Habsburgs, and supported by Saxony and Brandenburg-Prussia, Gustavus won a series of victories over Imperial forces, including Breitenfeld in September 1631, then Rain in April 1632.[7]

Despite the death of Gustavus at Lützen in November, Sweden and its German Protestant allies formed the Heilbronn League in April 1633, once again financed by France.[8] In July, the coalition defeated an Imperial army at Oldendorf in Lower Saxony; a few months later, Emperor Ferdinand II dismissed his leading general Albrecht von Wallenstein, who was assassinated by Imperial agents in February 1634.[9]

The removal of Wallenstein strengthened Emperor Ferdinand's position within the Empire but made him more reliant on Spanish military resources. Their main objective was to re-open the Spanish Road to support their campaign against the Dutch Republic and the focus now shifted to the Rhineland and Bavaria.[10] Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, newly appointed Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, recruited an army of 11,700 in Italy, which in May crossed the Alps through the Stelvio Pass. At Rheinfelden, he linked up with forces previously commanded by the Duke of Feria, who died in January 1634. This brought his numbers up to 18,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.[11]

The Swedish army and their German allies fought as separate units with diverging objectives, and thus suffered from less coherent leadership. While Johan Banér and Hans von Arnim invaded Bohemia, Gustav Horn tried to block the Spanish by investing Überlingen, and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar sought to consolidate his position in Franconia by taking Kronach.[12] Neither attempt was successful and left Regensburg isolated, which was besieged on 23 May by an Imperial army of 25,000 under Ferdinand of Hungary. Horn and Bernhard met at Augsburg on 12 July and marched towards the Bohemian border, hoping the threat of them combining with Arnim would force Ferdinand to abandon the siege.[12]

Although they defeated an Imperial blocking force under Johann von Aldringen at Landshut on 22 July, the siege continued and Regensburg surrendered on 26 July.[13] With 15,000 men, Ferdinand marched down the Danube (see Map) and reached Donauwörth on 26 August, where he turned aside to besiege the Swedish-held town of Nördlingen, which had to be taken before continuing his advance. Horn and Bernhard marched to Bopfingen but delayed their attack; with both sides short of supplies and suffering from plague, they were confident the outnumbered Imperials would have to withdraw.[14]

However, on 2 September Ferdinand of Hungary was joined by his Spanish cousin and Nördlingen nearly fell to an assault two days later.[3] At a council of war held on 4 September, the Protestant commanders agreed the political impact of its loss outweighed the military risk of accepting battle. Although they had just been joined by 3,400 men under Scharffenstein, Horn wanted to wait for additional troops but these were a week's march away. Bernhard argued they could not wait and urged an immediate attack, while he estimated the Spanish reinforcements as less than 7,000. The true figure was over 18,000, which meant the Habsburg army totalled over 33,000, compared to the Protestant figure of around 26,000. This included 8,000 poorly trained Württemberg militia, many of whom had previously served in the Imperial army.[15]

Battle

- The Battle in Three Maps

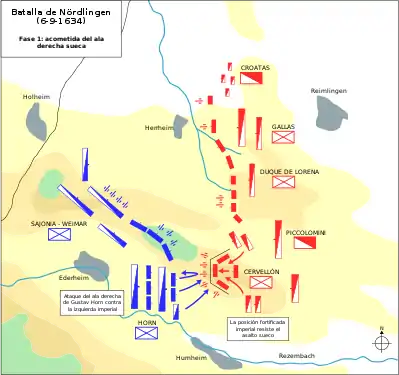

Phase 1; (Blue) Swedish assault takes the Albuch before being repulsed by (red) Spanish infantry and Bavarian cavalry led by Ottavio Piccolomini

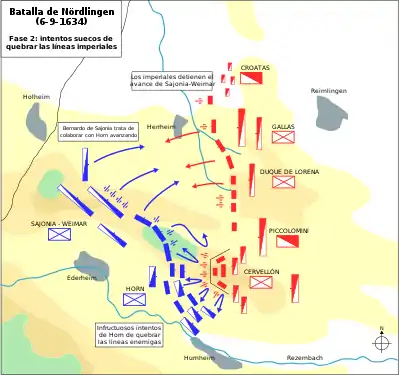

Phase 1; (Blue) Swedish assault takes the Albuch before being repulsed by (red) Spanish infantry and Bavarian cavalry led by Ottavio Piccolomini Phase 2; Assaults by Swedish-German infantry are repulsed; von Taupadel launches a cavalry attack against the Imperial left but is forced back

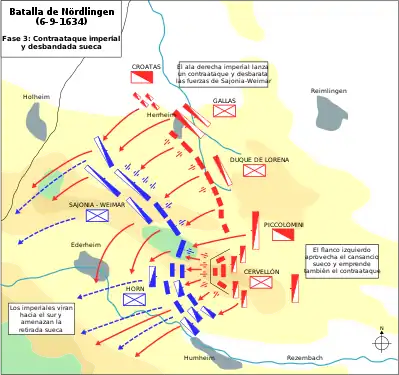

Phase 2; Assaults by Swedish-German infantry are repulsed; von Taupadel launches a cavalry attack against the Imperial left but is forced back Phase 3; Horn retreats, exposing Bernhard's right, while Croatian cavalry outflank him on the left; a general Spanish-Imperial advance routs the Protestant army

Phase 3; Horn retreats, exposing Bernhard's right, while Croatian cavalry outflank him on the left; a general Spanish-Imperial advance routs the Protestant army

Early on 5 September, the Protestant army broke camp and first feinted west as if retreating to Ulm, then moved across country to seize a line of hills two kilometres south of Nördlingen.[3] Around 16:00, the advance guard under Bernhard came into contact with Spanish and Imperial pickets holding the western edge of the hills. Although their experienced subordinates, Matthias Gallas and Count Leganés, advised retreat, the two Ferdinands made the decision to stand their ground and fighting continued until after midnight. The Habsburg forces were driven off some of the hills but retained the Albuch, which was key to the position as it prevented them being outflanked. This was occupied by 6,600 Spanish and 1,500 Bavarian infantry under Ottavio Piccolomini, who spent the night digging trenches and positions for a battery of 14 guns. A detachment of 2,800 Bavarian cavalry was stationed directly behind, with the rest of their army holding a line running north to Nördlingen (see Phase 1 map above).[16]

Leaving the Württemberg militia to guard the baggage train, the bulk of the infantry under Horn and 4,000 cavalry led by Scharffenstein was tasked with taking the Albuch, whose loss would force the Spanish-Imperial forces to retreat and abandon the siege of Nördlingen. At the same time, Bernhard's troops would distract the Imperial right, although it soon became clear he was badly outnumbered and thus restricted to limited skirmishing.[17] At 5:00 am on 6 September, the Swedish artillery opened fire on the Albuch, followed by a general assault; although the first wave was repulsed with heavy losses, the second composed of veteran units overran the Bavarian infantry and for a short period it appeared Horn had won a great victory. However, a powder wagon exploded, causing confusion among the Swedish troops, and the Spanish infantry took advantage of this to drive them back to their starting positions.[18]

Horn rallied his men and made a series of assaults over the next few hours, all of which were beaten back by the veteran Spanish units (see Phase 2 map above).[19] Despite Bernhard's skilful use of artillery on the left, which forced the Imperials to hold their positions, their superior numbers allowed Leganés and Gallas to feed in a constant stream of fresh troops to support their comrades on the Albuch.[20] Two brigades of Bernhard's infantry joined the assault but were attacked by Bavarian cavalry before reaching the hill, while an attack against the Imperial left by his own under von Taupadel was soon forced back upon their lines. By midday, Horn's men were exhausted after making up to 15 separate attempts to capture the Albuch and began to retreat.[3]

Their withdrawal exposed Bernhard's infantry on the other hills, while Croat light cavalry simultaneously outflanked him on the left. Under this pressure, the Protestant army disintegrated, despite attempts to rally them and suffered heavy losses during the pursuit (see Phase 3 map above). Two thousand of the militia guarding the baggage were killed and another 4,000 taken prisoner, most of whom then enrolled in the Imperial army. Scharffenstein, previously a senior commander in the Bavarian army, was captured and later executed for treason; Horn was also taken and held in custody until 1642.[21] In addition to prisoners, the Protestants suffered a total of 8,000 casualties, compared to 3,500 for their opponents;[lower-alpha 2] Bernhard and von Taupadel reached Heilbronn with the remaining 12,000 men a few days later.[22]

Aftermath

Nördlingen has been described as "arguably the most important battle of the war", a result which effectively destroyed Swedish power in southern Germany.[23] The Imperial army retook most of the Duchy of Württemberg and moved into the Rhineland, while Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna faced pressure from his domestic opponents to end the war. In December, two of their main allies, Saxony and Hesse-Darmstadt, negotiated a peace agreement with Emperor Ferdinand, later formalised in the May 1635 Treaty of Prague. Its terms included the dissolution of the Heilbronn and Catholic Leagues and the treaty is generally seen as the point when the Thirty Years' War ceased to be primarily a German religious conflict.[24]

However, the collapse of the anti-Habsburg alliance in Germany now prompted direct French intervention. In February 1635, Cardinal Richelieu signed a treaty agreeing a joint Franco-Dutch offensive in the Spanish Netherlands, while a French army under Henri, Duke of Rohan, cut the Spanish Road by invading the Valtellina in March.[25] This was followed in April by a new alliance with Sweden, as well as financing an army of 12,000 under Bernard of Saxe-Weimar in the Rhineland. In May, France formally declared war on Spain, starting the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish War.[26] Two years after Nördlingen, the battle of Wittstock in October 1636 was a resounding victory for the Swedish forces, and corrected any delusions harboured by the Imperials that the Swedish army was a spent force after the battle of Nördlingen.

Notes

References

- ↑ Guthrie 2001, p. 273.

- 1 2 3 David 2012, p. 406.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson 2009, p. 545.

- 1 2 Wilson 2009, p. 549.

- 1 2 3 Parker 1997, p. 126.

- ↑ (German: Schlacht bei Nördlingen; Spanish: Batalla de Nördlingen; Swedish: Slaget vid Nördlingen)

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Riches 2012, p. 160.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, p. 358.

- ↑ Kamen 2003, pp. 385–386.

- ↑ Wilson 2009, p. 544.

- 1 2 Wedgwood 2005, p. 369.

- ↑ Wilson 2009, p. 543.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, p. 370.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ Wilson 2009, p. 546.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, p. 373.

- ↑ Guthrie 2001, pp. 271–272.

- ↑ Guthrie 2001, p. 272.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, p. 375.

- ↑ Parker 1997, p. 192.

- ↑ Wilson 2009, p. 547.

- ↑ Kamen 2003, p. 386.

- ↑ Parker 1997, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Kamen 2003, p. 387.

- ↑ Wedgwood 2005, pp. 389–191.

Sources

- David, Saul (2012). The Encyclopedia of War. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4093-8664-3.

- Guthrie, William (2001). Battles of the Thirty Years War: From White Mountain to Nordlingen, 1618–1635. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-32028-6.

- Kamen, Henry (2003). Spain's Road to Empire. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-14-028528-4.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1997) [1984]. The Thirty Years' War. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12883-4. (with several contributors)

- Riches, Daniel (2012). Protestant Cosmopolitanism and Diplomatic Culture: Brandenburg-Swedish Relations in the Seventeenth Century (Northern World). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24079-7.

- Wedgwood, C. V. (2005) [1938]. The Thirty Years War. New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1-59017-146-2.

- Wilson, Peter (2009). The Thirty Years War: Europe's Tragedy. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06231-3.

%252C_by_Michiel_van_Mierevelt.jpg.webp)