| Beautiful demoiselle | |

|---|---|

_male_3.jpg.webp) | |

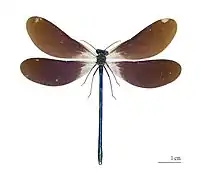

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Odonata |

| Suborder: | Zygoptera |

| Family: | Calopterygidae |

| Subfamily: | Calopteryginae |

| Tribe: | Calopterygini |

| Genus: | Calopteryx |

| Species: | C. virgo |

| Binomial name | |

| Calopteryx virgo | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

The beautiful demoiselle (Calopteryx virgo) is a species of damselfly belonging to the family Calopterygidae. It is found in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia.[1] It is often found along fast-flowing waters.

Subspecies

There are currently five known subspecies:[3]

- Calopteryx virgo britannica Conci, 1952

- Calopteryx virgo festiva (Brullé, 1832) (eastern Mediterranean) [1]

- Calopteryx virgo meridionalis Sélys, 1853 (western Mediterranean and south-west France) [1]

- Calopteryx virgo padana Conci, 1956 (northern Italy) [4]

- Calopteryx virgo virgo (Linnaeus, 1758)

Calopteryx virgo meridionalis

Calopteryx virgo meridionalis C. v. meridionalis. Mounted specimen

C. v. meridionalis. Mounted specimen

Description

Eggs and larvae

Females can lay up to 300 eggs at a time on floating plants, such as water-crowfoot. Like the banded demoiselle, they often submerge underwater to do so, and the eggs hatch around 14 days later. The larvae are stick-shaped and have long legs. They develop over a period of two years in submerged vegetation, plant debris, or roots. They usually overwinter in mud or slime.

The larvae of the beautiful demoiselle develop over 10 to 12 stages, each of which ends with a moult. The body length varies and depends on environmental conditions. In the final stage (F-0-stage), larvae are 3.5–4.6 millimetres long and weigh about 4 milligrams, slightly smaller than those of the banded demoiselle. The larvae of the beautiful demoiselle can be recognized by the bristles of the gills on their abdomen.

The body of the larvae shows only a relatively small adjustment to the fast-flowing waters of their habitat. The body is not flattened, but it is very slim, and the legs are long and end with strong claws. Because they reside within the water, and mainly in quiet areas, the danger of being swept by the flow is relatively low. If this happens, they stretch out to grab onto passing vegetation or substrate.

Adult

Beautiful demoiselle can reach a body length of 49–54 millimetres (1.9–2.1 in),[5] with a hindwing length of 31–37 millimetres (1.2–1.5 in).[6] These large, dark damselflies have small, lateral, hemispherical eyes; two pairs of wings similar in shape; and a slender abdomen. The wings have a dense internal network of veins, and can be transparent or uniformly colored at their basal area. This species presents an evident sexual dimorphism in colour pattern.[6]

The male usually has much more extensive pigmentation on the wings than other Calopteryx species in its range. In the southeast of its range (the Balkans and Turkey), the wings are entirely metallic blue. In other areas, the wings have clear spots at the base and the tip. Immature males have brown wings, as the metallic blue wing color develops only with age.[7] They have metallic blue-green bodies and blue-green eyes.[6] The female has dark brown iridescent wings, a white patch near the tip of the wings (called a pseudopterostigma) and a metallic green body with a bronze tip of the abdomen.[6]

This species is similar to the banded demoiselle (Calopteryx splendens), another British damselfly with coloured wings.[7]

Distribution

Beautiful demoiselle are distributed across all of Europe with the exception of the southwestern Iberian Peninsula, the Balearic Islands, and Iceland.[8][1] In the north, it extends to the Arctic Ocean, much farther north than the banded demoiselle. Its southern populations can be found as far south as Morocco and Algeria.[9] The eastern subspecies of C. v. japonica, found on the Japanese islands, is under debate as to whether it is a separate species. The beautiful demoiselle is mostly found in lowland locations. Regular findings come from areas up to a maximum height of 980 m above sea level; occasionally, they may be found up to 1,200 meters in altitude, such as in the Alps.

Habitat

Biotope

Beautiful demoiselles live mainly near small to medium-sized streams and creeks.[7] They prefer a relatively low water temperature and a moderate to fast flow. The water must not be nutrient-rich (eutrophic). In the northern part of their range, such as in Norway and Finland, they are also found near medium-sized rivers or even larger streams. The waters are usually in the immediate vicinity of forests.

Larval habitat

The larvae live in streams, and are mainly dependent on the water plants. The larvae need the stems and leaves to hold on to, especially in areas with strong currents. Because of this, it is extremely rare to find them in barren locations, flat expiring banks, or areas with a smooth stone floor. They also live in small natural lakes or ponds with limestone bedrock. They live in quiet areas between alluvial leaves or exposed roots. They can be found on submerged plants such as waterweed (Elodea sp.), water crowfoot (Ranunculus fluitans), or other plants submerged between a few centimetres to several decimetres.

Compared with the larvae of the banded demoiselle, the larvae of the beautiful demoiselle prefer quieter areas of the water, since slower flows allow for a more effective absorption of oxygen underwater. Only in very rare cases are the larvae present in stagnant water. The larvae reside mainly in vegetation.

An important factor in the occurrence of beautiful demoiselles is the oxygen in the water. The larvae are much more sensitive to oxygen deficiency than the larvae of the banded demoiselle, and need sufficient oxygen saturation in the water. Waters with high levels of sediment and sludge are not a good habitat for the larvae.

Another key factor for the occurrence of the larvae of the beautiful demoiselle is the temperature of the water. This species prefers cooler, shadier areas of the water, with an optimal summer average temperature between 13 and 18 °C. At temperatures above 22 °C, injuries to larvae were observed, as well as a reduced hatchability of eggs. Individual populations may adapt to permanently higher temperatures.

Adult habitat

The habitat of adults corresponds to the nearby larval habitat. Unlike the adults of the banded demoiselle, beautiful demoiselle may be found in forest clearings, and very rarely on the banks of larger ponds. Trees and shrubs are used as resting places, with the beautiful demoiselle often resting on high herbaceous plants such as the large nettle (Urtica dioica).

The breeding habitats are similar to the larval habitat. They prefer cool, shady waterways, with a more or less strong current, and near-natural vegetation and bank structure. This tends to be meadow and pasture streams in the area, and rarely forest. Riparian vegetation also plays a role as a windbreak. Due to their broad wings, the beautiful demoiselle can be blown away by the wind more easily than other species of damselflies.

Behaviour

Males are territorial, and will perch on bankside plants and trees where they wait for females or chase passing insects, often returning to the same perch.[7] Males can stray well away from water, and females live away from water unless laying eggs or seeking a mate.

Sexually mature beautiful demoiselles display pronounced territorial behavior, occupying territories that they defend against other males. Their defense consists mostly of threatening gestures, spreading their wings and being clearly visible. Optimal territories correspond to optimal nesting places for the females. They are characterized by an increased flow and a suitable oviposition substrate in the potential breeding sites. The size of the territories and their distance apart is dependant on the population density as well as availability of suitable habitat. Males who do not occupy a territory may stay in bankside vegetation and try to fill vacant spots. Especially when only a few males are present, territorial defense is very aggressive. With a higher number of competing males, aggression decreases significantly.

The males will defend their territories from exposed perches in the vegetation which extend over the water, sometimes on vegetation or rocks cushions amid the waters. From here they will survey their territory and perform a behaviour known as "wing lapping", where the wings are quickly flapped down and then slowly lifted. It is believed that this is mainly used for communication, however it may also help ventilate the thorax, possibly playing a role in thermoregulation.

Mating and egg laying

Beautiful demoiselle mating is similar to others in the genus Calopteryx. Females will fly over the water in search of suitable nesting places, passing through the territories of males along the way. The males will fly towards the female, demonstrating acrobatics which are only seen during courtship, and showing the underside of their abdomen. The rear three sections of the abdomen are much brighter and are presented to the female. The male will then lead the female to a nesting site and will circle the area once as the female lands. The male will then hover, waiting until the female has landed, showing her willingness to mate. The pair will arrange themselves in a "mating wheel", and mating can last between 40 seconds and 5 minutes.

After mating, the male releases the female and proceeds to show the female the nesting site. The females abdomen will droop during a post-copulatory rest which lasts a few seconds, after which they follow the male. The eggs are laid in the stems of aquatic plants at or below the water level, where the female can submerge for up to 90 minutes. Unlike almost all other species of damselflies, the female climbs upside down onto the stem and stabs the eggs into the stem using their ovipositor, orienting them almost vertically. While the female is laying the eggs, the male waits above, defending the female against other males. Both sexes mate several times a day for several weeks until their death.

Larval development

The development of the damselfly can be divided into three periods. First, the early development after fertilization where the basic shape of the body is formed, followed by the continued development of the body shape up until they hatch from the egg, and finally the larval development of hatched individuals up until the formation of wings.

The eggs of the beautiful demoiselle are on average 1.2 millimetres long and 0.2 millimetres wide, with a spindle-shaped structure. At the pointed end of the egg are four holes which are used by the male to inject sperm. The eggs also have a funnel-like appendix on this which allows them to project outwardly from the plant stem. The colour of the eggs change from a bright yellow when freshly laid to a yellow-brown or yellow brown as they age.

Once the eggs are laid and fertilized, the embryonic development of the damselfly begins. This was first described for the beautiful demoiselle in 1869, and was the first description of embryonic development of an insect. From outside, the development of the embryo can be see by a slight change in the length and shape of the egg. The upper part of the egg bulges slightly, which the lower part becomes concave. Eggs typically hatch between 20 days to one month after fertilization.

In the Middle East, the larval development of the beautiful demoiselle usually takes 6–8 weeks, mainly due to the preference for cooler waters. This is somewhat longer than that of the banded demoiselle. Larvae continue to develop over the winter, with some metamorphosing in the following year. If the water is cooler during breeding, a greater the portion of larvae will overwinter twice, giving a development time of nearly two years (semivoltine development). Studies have shown that this might modify the relationship between univoltine and semivoltine larvae within a body of water and clear in the course of the river and increase the water temperature moves toward univoltiner larvae.

The larvae, like other damselflies, are predatory and feed primarily on other insect larvae. This includes the larvae of black flies, midges, stoneflies, and mayflies, and they may also feed on amphipods. The larvae will defend themselves against over damselfly larvae, especially those of its own kind.

The larvae are much more sensitive to changes in habitat than the banded demoiselle, especially to temperature fluctuations. Only a few days of oxygen deprivation are needed for mortality to increase rapidly, and even after acceptable oxygen conditions return there will still be a higher rate of mortality and birth defect among affected individuals. This is mainly because beautiful demoiselles do not efficiently absorb oxygen from water. This differs from the banded damselfly, who have thin-skinned tracheogenic appendages which make them less sensitive fluctuations in oxygen supply. The inefficiency of their oxygen uptake is balanced by their choice of habitat, since both increased flow and cooler water increase their absorption capacity.

Hatching

Adult beautiful damselflies begin to emerge at the end of April, and continue until the end of September, depending on weather.[7] Most hatching occurs from late May to late June. The transformation of larvae to adults is not synchronous and lasts throughout the season until about mid-July. The newly hatched damselflies typically stay near their hatching site for 10 days, living in the surrounding vegetation until their wings are fully colored. After this, they return to the water and begin mating. The adults only live for one season; their adult lifespan is about 40 to 50 days.

Males will stay in sunlit areas throughout the day, typically reaching the water in the early morning. In Central Europe, they typically arrive between 7:00 A.M. and 9:00 A.M. In shaded environments, the damselflies will arrive later, and are usually seen basking on the top of surrounding vegetation. Females fly over the waters throughout the day in search of suitable nesting sites, and both sexes will engage in hunting, advertising, mating and egg laying during the warm midday hours. At night, the damselflies will return to the same sunlit areas within the vegetation where the started their day.

Male beautiful damselflies do not range far from their breeding, hunting, and resting areas, only going a relatively small 20–100 metres (66–328 ft). Females have been observed flying distances of up to 4 miles (6.4 km) per day.

Conservation

The beautiful demoiselle is considered stenoecious due to their very narrow ecological requirements. The larvae in particular can only thrive in natural bodies of waters that have little human influence. In the largest part of their range, the species is very rare. It is completely absent in major cities and industrial centers, and even in regions with strongly pronounced agricultural use it is found only rarely. Because of this, the Red Data Book (1998) of Germany classifies it as endangered in some states, even in danger of extinction. This is the same in Austria, Switzerland and other Central European countries. The IUCN, however, considers it a species of least concern.[1]

Several factors are known to impact the population of beaufitul damselflies is the necessity of certain aquatic plants. The eutrophication of some waters by household or agricultural wastewater has contributed to the decline of some populations. This causes an increase in algal blooms, decreasing the available oxygen in the affected waters and affecting the type of vegetation present. The new vegetation may not by accepted by the females as oviposition sites. In addition, the larvae have less to hold onto the current, and the algae and dirt particles settle into their gills restricting respiration. The algae is followed by a proliferation of weeds and ultimately a silting of water bodies.

However, natural waters with low water pollution do not guarantee a suitable habitat. Fast growing plants, such as meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), the stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) or Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera), may cause the area to become overgrown. Additionally if tree growth on the waters edge results in a closed canopy, the damselflies will lack the necessary sunlight. These issues can be counteracted by regular removal of some vegetation, or even a partial thinning of trees and shrubs. In intensively used agricultural areas with regular use of manure fertilizer, a bare strip a few meters wide can prevent eutrophication of riparian areas.

See also

Bibliography

- Georg Rüppell: . The Demoiselles Europe The New Brehm library . Westarp Sciences, Hohenwarsleben 2005, ISBN 3-89432-883-5.

- Gerhard Jurzitza: . the cosmos-dragonfly leader Franckh Kosmos Verlag GmbH & Co., Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-440-08402-7.

- Heiko Bellmann: . watching dragonflies - determine nature Verlag, Augsburg, 1993, ISBN 3-89440-107-9.

- K. D. B. Dijkstra, illustrations: R. Lewington, Guide des libellules de France et d'Europe, Delachaux et Niestlé, Paris, 2007, (ISBN 978-2-603-01639-8).

- Klaus Sternberg, Rainer Buchenwald . Dragonflies Baden-Württemberg, Volume 1 Eugen Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8001-3508-6.

- Misof, Bernhard; Anderson, Cort L.; Hadrys, Heike (2000). "A phylogeny of the damselfly genus Calopteryx (Odonata) using mitochondrial 16S rDNA markers". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 15 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0724. PMID 10764530.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Boudot, J.-P. (2022) [amended version of 2018 assessment]. "Calopteryx virgo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T165505A219967836. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T165505A219967836.en. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ↑ "Beautiful Demoiselle Calopteryx virgo (Linnaeus, 1758)". BioLib.

- ↑ Bisby F.A., Roskov Y.R., Orrell T.M., Nicolson D., Paglinawan L.E., Bailly N., Kirk P.M., Bourgoin T., Baillargeon G., Ouvrard D. Catalogue of life Archived 2018-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Checklist of the Italian fauna". www.faunaitalia.it.

- ↑ "Beautiful Demoiselle - Encyclopedia of Life". eol.org.

- 1 2 3 4 "Calopteryx virgo meridionalis at Grid.unep.ch". Archived from the original on 2018-03-19. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Beautiful Demoiselle". British Dragonfly Society. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ↑ "Fauna europaea".

- ↑ See "dissemination". In: Klaus Sternberg, Rainer Buchenwald . dragonflies Baden-Württemberg, Volume 1 Eugen Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, p 203 ISBN 3-8001-3508-6 .

External links

- Schorr, M. and Paulson, D. 2015. World Odonata List. Tacoma, Washington, USA

Media related to Calopteryx virgo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Calopteryx virgo at Wikimedia Commons