| Beorn | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Race | Skin-Changer |

| Book(s) | The Hobbit (1937) |

Beorn is a character created by J. R. R. Tolkien, and part of his Middle-earth legendarium. He appears in The Hobbit as a "skin-changer",[T 1] a man who could assume the form of a great black bear. His descendants or kinsmen, a group of Men known as the Beornings, dwell in the upper Vales of Anduin, between Mirkwood and the Misty Mountains, and are counted among the Free Peoples of Middle-earth who oppose Sauron's forces during the War of the Ring. Like the powerful medieval heroes Beowulf and Bödvar Bjarki, whose names both mean "bear", he exemplifies the Northern courage that Tolkien made a central virtue in The Lord of the Rings.

Appearances

Beorn lives in a wooden house on his pasture-lands between the Misty Mountains and Mirkwood, to the east of the Anduin. His household includes an animal retinue (with horses, dogs, sheep, and cows); according to Gandalf, Beorn does not eat his cattle, nor hunt wild animals. He grows large areas of clover for his bees.[T 1] Gandalf believes that Beorn is either a descendant of the bears who had lived in the Misty Mountains before the arrival of the giants, or a descendant of the men who had lived in the region before the arrival of the dragons or Orcs from the north.[T 1]

He is of immense size and strength for a man and retains these attributes in bear-form. He has black hair (in either form) and a thick black beard and broad shoulders. While not a "giant" outright, Beorn's human form is of such great size that the three and a half foot tall Bilbo judges that he could have easily walked between Beorn's legs without touching his body. Beorn names the large rock by the River Anduin the Carrock; he had created the steps that led from its base to its flat top.[T 1]

Beorn receives Gandalf, Bilbo Baggins and thirteen Dwarves and aids them in their quest to reclaim their kingdom beneath the Lonely Mountain. He is convinced of their trustworthiness after going out and confirming their tale of encountering the Goblins of the Misty Mountains and Gandalf's slaying of their leader, the Great Goblin. As well as giving the group much-needed supplies and lodging, Beorn provides them with vital information about what path to take while crossing Mirkwood.[T 1]

_-_cropped.png.webp)

Later, hearing of a vast host of Goblins on the move, Beorn arrives at the Lonely Mountain in time to strike the decisive blow in the Battle of Five Armies. In his bear form he kills the Goblin leader, Bolg, and his bodyguards. Without direction, the Goblin army is scattered, forming easy pickings for the other armies of Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Eagles. Beorn often leaves his home for hours or days at a time, for purposes not completely explained.[T 1] It is said that "Beorn indeed became a great chief afterwards in those regions and ruled a wide land between the mountains and the wood; and it is said that for many generations the men of his line had the power of taking bear's shape and some were grim men and bad, but most were in heart like Beorn, if less in size and strength."[T 2]

In the years between the Battle of Five Armies and the War of the Ring, Beorn emerges to become a leader of the woodmen living between the Anduin river and the fringes of Mirkwood.[T 2] As stated by Glóin in The Fellowship of the Ring, the Beornings "keep open the High Pass and the Ford of Carrock."[T 3] In the events leading up to the War of the Ring, the Beornings assist Aragorn, who was taking Gollum to Mirkwood so that Gandalf could find out what Gollum knew about the One Ring, to cross the Anduin.[T 4]

Concept and creation

Bear-like warrior

_sid_103).jpg.webp)

In naming his character, Tolkien used beorn, an Old English word for "man" and "warrior" (with implications of "freeman" and "nobleman" in Anglo-Saxon society).[2] The name is cognate with the Scandinavian names Björn (Swedish and Icelandic) and Bjørn (Norwegian and Danish), meaning bear; and the figure of Beorn can be related to the traditional Northern heroes Bödvar Bjarki and Beowulf, both of whose names also mean "bear".[3][4] The name Beorn survives in the name of the Scottish town Borrowstounness, which is derived from the Old English Beornweardstun ("the town with Beorn as its guardian").[5][6] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey comments that Beorn exemplifies the heroic Northern courage that Tolkien later made a central virtue in his larger novel, The Lord of the Rings, as he is ferocious, rude, and cheerful, characteristics that reflect his huge inner self-confidence.[7]

Paul W. Lewis, writing in Mythlore, calls Beorn "essentially a berserker in battle", alluding to the Old Norse warriors who fought in a trance-like state of fury. The term means "bear-shirt"; its Old Norse form, hamrammr, was taken by Tolkien to mean "skin-changer", and he gave Beorn this capability.[1]

| Name or term | Language | Literal meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beorn | Old English | "Bear" | Man as strong as a bear, warrior, chieftain; cf modern Scandinavian names Björn, Bjørn |

| Beowulf | Old English | "Bees' wolf" = honey-eater, bear | Hero of the epic poem Beowulf |

| Bödvar Bjarki | Old Norse | "Warlike little-bear" | Hero of Hrólfs saga kraka; a skin-changer, bear by day, a man by night |

| berserker | Old English | "Bear-shirt" | Warrior who fights in a trance-like state of fury |

| hamrammr | Old Norse | Taken by Tolkien as "Skin-changer" | Were-bear, berserker |

Distinctive loner

Beorn's name for the large rock in the River Anduin, the Carrock, on the other hand, is not Germanic – whether Norse or English – but Brittonic, related to Welsh carreg, "a stone".[8] The medievalist Marjorie Burns notes the tension between "British" and Norse in Tolkien's handling of his materials. This is one of many instances of what Clyde S. Kilby called "contrasistency" – Tolkien's apparently intentional "doubleness" or switching between opposite viewpoints. Burns comments that Beorn's story and character embody tensions "between forest and garden, home and wayside, comradeship and solitude, risk and security" and in her view most strongly between "freedom and obligation", not to mention bear and man.[9] Burns calls Beorn one of

the most striking of Tolkien's individuals ... his innate, one-of-a-kind loners, the honorable isolationists, who dwell in secluded domains and ... are distinctive, free, self-reliant but respectful of other lives and hostile only to those deserving hostility.[9]

The Tolkien scholar Justin Noetzel compares Beorn to Tom Bombadil in The Lord of the Rings, another one-of-a-kind figure strongly attached to the place where he lives. Both have "an intimate connection with the natural world", using this to help their visitors, protecting them from local dangers, whether wolves and goblins, or Old Man Willow and the Barrow-wight.[10]

Norse and English

Burns writes that Beorn's character, too, contains a complex tension between Norse and English. As a skin-changer he is evidently pagan and Norse; but his vegetarianism, reluctance to use metal, home-loving nature and flower garden all look more compatible with Christianity and Englishness, without being those things specifically. Burns comments that he is thus[9]

in the best Tolkienian tradition, a being of two extremes: both ruthless and kind, a bear and man, a homebody and wanderer, a berserker and pacifist in one.[9]

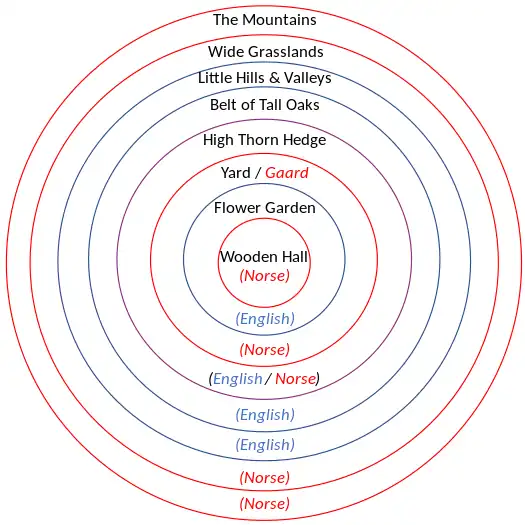

Burns states that this blending of wild Norse with civilised English can be seen in Middle English literature such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Gawain meets a big rugged Beorn-like shape-changer, Bertilak (the Green Knight), who lives in a castle in an oak forest, and speaks with Christian courtesy. She calls Sir Gawain's oaks "entirely druidic", suggesting Celtic mythology or Arthurian legend. But she notes that "the oak was sacred to [the Norse god] Thor", allowing Tolkien to assemble Celtic and Norse elements in his composite Middle-earth. Further, she writes, Beorn's home has an almost diagrammatic set of circles of "mixed English and Nordic characteristics": at the centre the Nordic hall; the "Shire-like flower garden" and courtyard; a wider yard (Norse gaard) with its outbuildings; a "high thorn-hedge" in English style; a "belt of tall and very ancient oaks" (English or Norse) and fields of flowers; little English-like hills and valleys with oaks and elms; "wide grass-lands, and a river running through it all", which remind Burns of Iceland; and finally "the mountains", evidently Norse.[9]

Diagram of Marjorie Burns's analysis of mixed Norse and English influence on Beorn's dwelling-place[9]

Diagram of Marjorie Burns's analysis of mixed Norse and English influence on Beorn's dwelling-place[9]

Adaptations

Film

The Swedish actor Mikael Persbrandt portrays Beorn in Peter Jackson's The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug and in its sequel The Battle of the Five Armies.[12] In the DVD commentary, the production team explain that they normally ensured that all characters had accents from the British Isles, but they made an exception for Beorn by letting Persbrandt use his natural Swedish accent. They reasoned that Beorn should have a distinctive and foreign-sounding accent, since he is the last survivor of an isolated race.[13] Jackson stated that many actors were auditioned for the role, but that Persbrandt captured Beorn's primitive energy. Richard Armitage, who played Thorin Oakenshield, said that Persbrandt had a fantastic voice, and that his accent was perfect for the role.[11]

Games

In the 2003 video game adaptation of The Hobbit the original encounter with Beorn at his lodge is omitted. Nevertheless, he shows up at the Battle of Five Armies to kill Bolg. Beorn only appears in bear form in the game.[14]

The Beornings appear as trainable units in The Lord of the Rings: War of the Ring (2003). The Beornings were added as a playable class to the massively multiplayer online role-playing game The Lord of the Rings Online in Update 15 (November 2014). One can play as a male or a female Beorning, and can transform into a bear after building up sufficient wrath during combat. Grimbeorn's Lodge in the Vales of Anduin is a starter area for the Beorning class, and Grimbeorn makes a brief appearance.[15]

References

Primary

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tolkien 1937, ch. 7 "Queer Lodgings"

- 1 2 Tolkien 1937, ch. 18 "The Return Journey"

- ↑ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings"

- ↑ Tolkien 1980, "The Hunt for the Ring"

Secondary

- 1 2 3 Lewis, Paul W. (2007). "Beorn and Tom Bombadil: A Tale of Two Heroes". Mythlore. 25 (3). Article 13.

- ↑ See definition: Bosworth, Joseph; Toller, T. Northcote. "BEORN". An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Online). Prague: Charles University., cognate to the Swedish and Icelandic björn

- ↑ Shippey 2001, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, p. 77.

- ↑ Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 951. ISBN 978-0-19-860561-4.

- ↑ Ross, David. Scottish Place-Names. Birlinn. p. 15. OCLC 213108856.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Erat, Vanessa; Rabitsch, Stefan (2017). ""Croeso i Gymru"–where they speak Klingon and Sindarin: An essay in appreciation of conlangs and the land of the red dragon". The Polyphony of English Studies: A Festschrift for Allan James. Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. p. 197. ISBN 978-3-8233-9140-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Burns, Marjorie (1990). "J. R. R. Tolkien: The British and the Norse in Tension". Pacific Coast Philology. 25 (1/2 (November 1990)): 49–59. doi:10.2307/1316804. JSTOR 1316804.

- ↑ Noetzel, Justin T. (2014). "Beorn and Bombadil: Mythology, Place and Landscape in Middle-earth". In Eden, Bradford Lee (ed.). 'The Hobbit' and Tolkien's Mythology. McFarland & Company. pp. 161–180. ISBN 9781476617954.

- 1 2 Löwenskiold, Ebba (10 December 2012). "Persbrandt hyllas för sin roll i "Hobbit"" [Persbrandt is praised for his role in The Hobbit]. Expressen (in Swedish).

Richard Armitage (Thorin): - Han har en fantastisk röst - för mig är rösten 80 procent av en karaktär. Hans accent var perfekt för rollen.

- ↑ Dunerfors, Alexander. "Persbrandt åker tillbaka för mera "Hobbit"" [Persbrandt goes back for more "Hobbit"]. MovieZine (in Swedish). Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, DVD Commentary.

- ↑ "The Hobbit Cheats". Games Radar. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ↑ Adams, Dan (24 November 2018). "Lord of the Rings: War of the Ring Review". IGN. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

Sources

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.