_(cropped).JPG.webp)

J. R. R. Tolkien was attracted to medieval literature, and made use of it in his writings, both in his poetry, which contained numerous pastiches of medieval verse, and in his Middle-earth novels where he embodied a wide range of medieval concepts.

Tolkien's prose adopts medieval ideas for much of its structure and content. The Lord of the Rings is interlaced in medieval style. The Silmarillion has a medieval cosmology. The Lord of the Rings makes use of many borrowings from Beowulf, especially in the culture of the Riders of Rohan, as well as medieval weapons and armour, heraldry, languages including Old English and Old Norse, and magic.

Context

The Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the Post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and transitioned into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery.[2] In the Early Middle Ages, the End of Roman rule in Britain c. 400 was soon followed by the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. By the sixth century, Anglo-Saxon England, "the bit [of Medieval culture] that Tolkien knew best",[1] consisted of many small kingdoms including Northumbria, Mercia, and East Anglia, engaged in ongoing warfare with each other.[3]

Tolkien the medievalist

J. R. R. Tolkien was a scholar of English literature, a philologist and medievalist interested in language and poetry from the Middle Ages, especially that of Anglo-Saxon England and Northern Europe. His professional knowledge of works such as Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight shaped his fictional world of Middle-earth. His intention to create what has been called "a mythology for England"[T 1] led him to construct not only stories but a fully-formed world with its own languages, peoples, cultures, and history, based on medieval languages including Old English, Old Norse, and Old High German,[4] and detailed knowledge of medieval culture and mythology.[5]

Medieval themes in Middle-earth

Poetry

We `heard of the `horns in the `hills `ringing,

the `swords `shining in the `South-`kingdom.

`Steeds went `striding to the `Stoning`land

as `wind in the `morning. `War was `kindled.

There `Théoden `fell, `Thengling `mighty,

to his `golden `halls and `green `pastures

in the `Northern `fields `never `returning,

`high lord of the `host.— from "The Mounds of Mundburg"[T 2]

Tolkien stated that whenever he read a medieval work, he wanted to write a modern one in the same tradition. He constantly created these, whether pastiches and parodies like "Fastitocalon"; adaptations in medieval metres, like "The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun" or "asterisk texts" like his "The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late" (from "Hey Diddle Diddle"); and finally "new wine in old bottles" such as "The Nameless Land" and Aelfwine's Annals. The works are extremely varied, but all are "suffused with medieval borrowings", making them, according to the Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff, "most readers' portal into medieval literature". Not all found use in Middle-earth, but they all helped Tolkien develop a medieval-style craft that found expression in his legendarium.[6] One of the most distinctively medieval poems in The Lord of the Rings is the Riders of Rohan's Old English-style lament for Théoden, written in what Tolkien called "the strictest form of Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse",[7] complete with balanced half-lines separated by a caesura, each half-line with two stresses, and a varying pattern of alliteration and use of multiple names for the same person.[8]

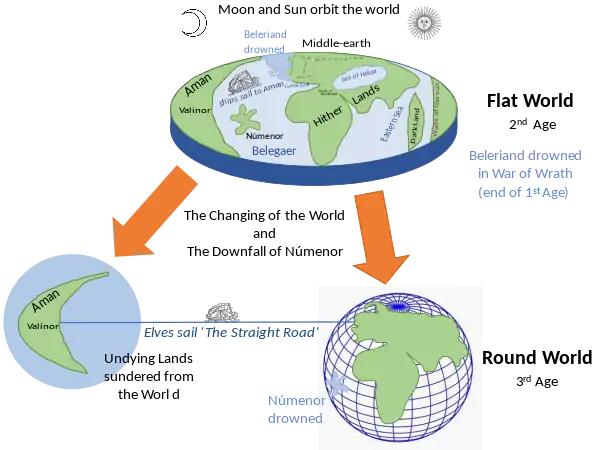

Cosmology

The cosmology of Middle-earth contains many medieval elements, but these are interwoven both with classical ideas like Atlantis, and modern cosmology with a round world. Tolkien was trying to reconcile different conceptions of the world, including the medieval Germanic migrations and the culture of Anglo-Saxon England, to create his mythology.[9] The world of Middle-earth is overseen by the godlike Valar, who resemble the medieval Norse Æsir, the gods of Asgard.[10] They function in some ways like angels in Christianity, mediating between the creator, named as Eru Ilúvatar, and the created world. They have free will, so that the Satanic Melkor is able to rebel against the will of Eru.[11]

Beowulf

_-_cropped.png.webp)

J. R. R. Tolkien drew on the medieval Old English poem Beowulf for multiple aspects of Middle-earth: for elements such as names, monsters, the importance of luck and courage, and the structure of society in a heroic and pagan age;[13] for aspects of style, such as creating an impression of depth[14] and adopting an elegiac tone;[15][16][17] and for its larger but hidden symbolism.[18]

He derived the names of Middle-earth races including Ents, Orcs, and Elves,[13] and names such as Orthanc and Saruman,[19] rather directly from Beowulf. The were-bear Beorn in The Hobbit has been likened to the hero Beowulf himself; both names mean "bear", and both characters have enormous strength.[12] Scholars have compared some of Tolkien's monsters to those in Beowulf. Both his trolls[20] and Gollum[21][22] share attributes with Grendel, while Smaug's characteristics closely match those of the Beowulf dragon.[23] Tolkien's Riders of Rohan are distinctively Old English, and he has made use of multiple elements of Beowulf in creating them, including their language,[24] culture,[25][26] and poetry.[8]

Tolkien admired the way that Beowulf, written by a Christian looking back at a pagan past, as he himself was, embodied a "large symbolism"[18] without ever becoming allegorical. That symbolism, of life's road and individual heroism, and that avoidance of allegory, Tolkien worked to echo in The Lord of the Rings.[18]

Weapons and armour

Tolkien's modelled his fictional warfare on the tactics and equipment of the Ancient and Early Medieval periods. His depictions of weapons and armour are based in particular on the Northern European culture of Beowulf and the Norse sagas.[27] As in his sources, Tolkien's weapons are often named, sometimes with runic inscriptions to show they are magical and have their own history and power.[28] In Tolkien's writings, as in the medieval epics, one weapon, the sword, announces a hero; his fate and the fate of his sword are linked closely together.[29][30]

Heraldry

Heraldry is a medieval system, by origin military, for displaying each knight or lord's identity. Tolkien invented quasi-medieval heraldic devices for many of the characters and nations of Middle-earth. His descriptions were in simple English rather than in specific blazon language. The emblems correspond in nature to their bearers, and their diversity contributes to the richly-detailed realism of his writings. Scholars note that Tolkien went through different phases in his use of heraldry; his early account of the Elvish heraldry of Gondolin in The Book of Lost Tales corresponds broadly to heraldic tradition in the choice of emblems and colours. Later, when he wrote The Lord of the Rings, he was freer in his approach; and in the complex use of symbols for Aragorn's sword and banner, he clearly departs from medieval tradition to suit his storytelling.[31][32][33][34]

Languages

Using his knowledge of medieval languages including Old English and Old Norse, Tolkien created his own languages for Middle-earth.[T 4] An item that the philologist and Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey suggests may have been crucial in his creation is the Old English word Sigelwara, found in the Codex Junius to mean "Aethiopian". Tolkien wondered why there should have been a word with this meaning, and after some years of research suggested it could be derived from Sigel, meaning both sun and jewel, and *hearwa, perhaps meaning soot, giving a conjectural original meaning for Sigelwara as "soot-black fire-demon". The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey links this to the Balrog fire-demon and the Silmaril sun-jewels.[35]

Magic

Middle-earth is pervaded with medieval-style magic, its races such as Wizards, Elves, and Dwarves each possessing their own inherent powers, which they could embody in magical artefacts such as a wizard's staff, Elvish waybread, and rings of power. Magical beasts derived directly from medieval concepts include dragons with their hoards of gold, birds such as crows and ravens carrying omens, and the ability to shapeshift into the form of an animal, like Beorn and the great fighting bear of The Hobbit. Norse mythology is rich in seeresses, dwarves, giants, and other monsters. The medieval world held that plants and other objects had magical powers. Tolkien absorbed all of these ideas and reworked them for his version of Middle-earth.[37][38][39] Thus for example the Hobbit Merry returns from Rohan with a magic horn, brought from the North by Eorl the Young, from the dragon-hoard of Scatha the Worm. Blowing it brings joy to his friends in arms, fear to his enemies, and it awakens the Hobbits to purify the Shire of Saruman's ruffians.[36] The Two Trees of Valinor derive from the magical medieval Trees of the Sun and the Moon. The two magical trees drip a wonderful balsam, and have the power of speech. They tell Alexander the Great that he will die in Babylon. Tolkien has adapted the story; his trees emit light, not balsam; and instead of prophesying death, their own deaths bring the era of immortality to an end.[40]

Interlacing

The Lord of the Rings has an unusual and complex medieval narrative structure, interlacing or entrelacement, in which multiple threads of story are maintained side by side. It was used especially in French medieval literature such as the 13th century Queste del Saint Graal,[41][42] and in English literature such as Beowulf[T 5] and The Faerie Queene.[42] Tolkien uses this medieval-style framework to achieve a variety of literary effects, including maintaining suspense, keeping the reader uncertain of what will happen and even of what is happening to other characters at the same time in the story; creating surprise and an ongoing feeling of bewilderment and disorientation. More subtly, the leapfrogging of the timeline by the different story threads allows Tolkien to make hidden connections that can only be grasped retrospectively, as the reader realises on reflection that certain events happened at the same time, and that these connections imply a contest of good and evil powers.[43]

Heroic romance

Tolkien described The Lord of the Rings not as a novel but as a heroic romance, meaning that it embodied medieval concepts unfamiliar or unfashionable in the 20th century, such as the hero, the quest, and interlacing. A traditional romance, according to the critic Northrop Frye, has six phases: the hero's strange birth – Frodo's parents both drown; his innocent youth – in the countryside of the Shire for Frodo, in Rivendell for Aragorn; the quest – for Frodo to destroy the Ring, for Aragorn to regain his Kingdom; confrontation with evil, as in Minas Tirith and the Battle of the Pelennor Fields; in the re-establishment of happiness, marriage, and fertility – Aragorn marries Arwen, Faramir marries Éowyn, Sam marries Rosie; and finally, the contemplative or penseroso phase, as characters depart or settle down – Frodo takes ship into the West, Sam becomes Mayor and has many children, Aragorn governs Gondor and Arnor as King.[44]

Elena Capra writes that Tolkien made use of the medieval poem Sir Orfeo, both for The Hobbit's Elvish kingdom, and for his story in The Silmarillion of Beren and Lúthien. That in turn influenced his "Tale of Aragorn and Arwen". In Capra's view, Sir Orfeo's key ingredient was the political connection "between the recovery of the main character's beloved and the return to royal responsibility."[45] Sir Orfeo is in its turn a reworking of the classical legend of Orpheus and Eurydice.[45]

Exile

Yvette Kisor writes that Tolkien made repeated use of the Old English theme of exile, seen in poems such as The Wanderer, Genesis, and Beowulf. She gives as examples Aragorn, rightful King of Gondor and Arnor, living in the wild; Frodo, who exclaims "But this would mean exile, a flight from danger into danger, drawing it after me"; the Númenóreans, the survivors of the destruction of their Atlantis-like land, living in Middle-earth; and the Noldor Elves, living across the sea from Valinor. She notes that Tolkien never describes the monster Gollum as an exile, commenting however that he meets Stanley Greenfield's four characteristics of an Old English exile. Among the numerous parallels, Kisor notes that "wretch", used repeatedly by Gandalf, Frodo, and Sam to describe Gollum, comes directly from Old English wreċċa, meaning "exile"; Old English poetry frequently, she states, uses wineléas wreċċa, "friendless exile".[46]

|

|

|---|---|

| The exile's status | Gandalf says "He is very old and very wretched." |

| The exile's state of mind | Gollum says "Poor hungry Sméagol." |

| The exile's journey | Gandalf says "He wandered in loneliness, weeping a little for the hardness of the world." |

| The exile's expression of deprivation | Gollum says "Poor, poor Sméagol, he went away long ago. They took his Precious, and he's lost now." |

References

Primary

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951.

- ↑ Tolkien 1955, book 5, chapter 6, "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields".

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #211.

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #163 to W. H. Auden, 7 June 1955

- ↑ Tolkien 1997, pp. 5–48.

Secondary

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 146–149.

- ↑ Power 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ "Anglo-Saxons: a brief history". Historical Association. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ↑ Chance 2003, Introduction.

- ↑ Bates 2003, ch. 1 "The Real Middle-earth".

- ↑ Rateliff 2014, pp. 133–152.

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #187 to H. Cotton Minchin, April 1956.

- 1 2 Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 46–53.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ↑ Garth 2003, p. 86.

- ↑ Wood 2003, p. 13.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 91–92.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 66, 74, 149.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 259–261.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, p. 239.

- ↑ Burns 1989, pp. 5–9.

- ↑ Hannon 2004, pp. 36–42.

- 1 2 3 Shippey 2005, pp. 104, 190–197, 217.

- ↑ Shippey 2001, pp. 88, 169–170.

- ↑ Fawcett 2014, pp. 29, 97, 125–131.

- ↑ Nelson 2008, p. 466.

- ↑ Flieger 2004, pp. 141–144.

- ↑ Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 109–111.

- ↑ Shippey 2001, pp. 90–97, 111–119.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 139–143.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Piela 2013, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Burdge & Burke 2013, pp. 703–705.

- ↑ Whetter & McDonald 2006, article 2.

- ↑ Flieger 1981, pp. 40–62.

- ↑ McGregor 2013, pp. 95–112.

- ↑ Purdy 1982, pp. 19–22, 36.

- ↑ Hriban 2011, pp. 198–211.

- ↑ Hammond & Scull 1998, pp. 187–198.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 48–49, 54, 63.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Eden 2005, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Bates 2003, ch. 9 "Magical Beasts", ch. 10 "Wizards of Wyrd", ch. 13 "Shapeshifters".

- ↑ Perry 2013, pp. 400–401.

- ↑ Garth 2020, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Seaman 2013, p. 468.

- 1 2 West 1975, pp. 78–81.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 181–183.

- 1 2 Thomson 1967, pp. 43–59.

- 1 2 Capra 2022.

- 1 2 Kisor 2014, pp. 153–168.

Sources

- Bates, Brian (2003). The real Middle-earth : exploring the magic and mystery of the Middle Ages, J.R.R. Tolkien and. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6319-3. OCLC 53343091.

- Burdge, Anthony; Burke, Jessica (2013) [2007]. "Weapons, Named". In Drout, Michael (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 703–705. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Burns, Marjorie J. (1989). "J.R.R. Tolkien and the Journey North". Mythlore. 15 (4): 5–9. JSTOR 26811938.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Capra, Elena Sofia (2022). ""Orfeo out of Care"". Thersites. 15 There and Back Again: Tolkien and the Greco–Roman World (eds. Alicia Matz and Maciej Paprocki). doi:10.34679/THERSITES.VOL15.209.</ref>

- Chance, Jane (2003). Tolkien the Medievalist. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47348-4. OCLC 53706034.

- Eden, Bradford Lee (2005). "The Real Middle-earth: Exploring the Magic and Mystery of the Middle Ages, J.R.R. Tolkien, and "The Lord of the Rings" (review)". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 256–257. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0015. ISSN 1547-3163. S2CID 170981408.

- Fawcett, Christina (2014). J.R.R. Tolkien and the morality of monstrosity (PhD). University of Glasgow (PhD thesis).

- Flieger, Verlyn (1981). "Frodo and Aragorn: The Concept of the Hero". In Isaacs, Neil D.; Zimbardo, Rose A. (eds.). Tolkien: New Critical Perspectives. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 40–62. ISBN 978-0813114088.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2004). "Frodo and Aragorn: The Concept of the Hero". In Rose A. Zimbardo and Neil D. Isaacs (ed.). Understanding the Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 122–145. ISBN 978-0-618-42251-7.

- Garth, John (2003). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. Houghton Mifflin. p. 86. ISBN 0-618-33129-8.

- Garth, John (2020). The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. Frances Lincoln Publishers & Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (1998) [1995]. "6. Patterns and Devices". J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. HarperCollins. pp. 187–198. ISBN 978-0-261-10360-3.

- Hannon, Patrice (2004). "The Lord of the Rings as Elegy". Mythlore. 24 (2): 36–42.

- Hriban, Catalin (2011). "The Eye and the Tree. The Semantics of Middle-earth Heraldry". Hither Shore. 8: 198–211.

- Kennedy, Michael (September 2001). "Tolkien and Beowulf – Warriors of Middle-earth". Amon Hen (171): 15–16. Archived from the original on 9 May 2006.

- Kisor, Yvette (2014). ""Poor Sméagol": Gollum as Exile in The Lord of the Rings". In Houghton, John Wm.; Croft, Janet Brennan; Martsch, N. (eds.). Tolkien in the New Century: Essays in Honor of Tom Shippey. McFarland. pp. 153–168. ISBN 978-1-4766-1486-1.

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137454690.

- McGregor, Jamie (2013). "Tolkien's Devices: The Herald[r]y of Middle-Earth". Mythlore. 32 (1): 95–112, Article 7.

- Nelson, Brent (2008). "Cain-Leviathan Typology in Gollum and Grendel". Extrapolation. 49 (3): 466–485. doi:10.3828/extr.2008.49.3.8.

- Perry, Michael W. (2013) [2007]. "Magic: Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 400–401. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Piela, Joseph (2013) [2007]. "Arms and Armour". In Drout, Michael (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Power, Daniel (2006). The Central Middle Ages: Europe 950–1320. The Short Oxford History of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925312-8.

- Purdy, Margaret R. (1982). "Symbols of Immortality: A Comparison of European and Elvish Heraldry". Mythlore. 9 (1): 19–22, 36, Article 5.

- Rateliff, John D. (2014). "Inside Literature: Tolkien's Explorations of Medieval Genres". In Houghton, John Wm.; Croft, Janet Brennan; Martsch, Nancy (eds.). Tolkien in the New Century: Essays in Honor of Tom Shippey. McFarland. pp. 133–152. ISBN 978-0-7864-7438-7.

- Seaman, Gerald (2013) [2007]. "Old French Literature". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Thomson, George H. (1967). "The Lord of the Rings: The Novel as Traditional Romance". Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature. 8 (1): 43–59. doi:10.2307/1207129. JSTOR 1207129.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1997) [1958]. Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics and other essays. London: HarperCollins.

- West, Richard C. (1975). "The Interlace Structure of The Lord of the Rings". In Jared Lobdell (ed.). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 77–94. ISBN 0-87548-303-8.

- Whetter, K. S.; McDonald, R. Andrew (2006). ""In the Hilt is Fame": Resonances of Medieval Swords and Sword- lore in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings". Mythlore. 25 (1). article 2. ISSN 0146-9339.

- Wood, Ralph C. (2003). The Gospel According to Tolkien. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-664-23466-9.

.jpg.webp)