| White Elephant | |

|---|---|

| Native names Polish: Biały Słoń Ukrainian: Білий слон | |

Observatory in 2018 | |

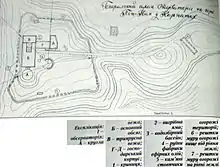

| Location | Pip Ivan, Verkhovyna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ukraine |

| Coordinates | 48°02′49″N 24°37′38″E / 48.04694°N 24.62722°E |

| Area | 500 square metres (5,400 sq ft)[1] |

| Elevation | 2,028 metres (6,654 ft)[1] |

| Built | 29 July 1938 |

| Built for | Polish Armed Forces / University of Warsaw |

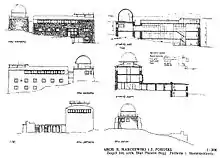

| Architect | K.Marczewski, J.Pohoski |

| Governing body | Verkhovyna Raion authorities along with State Emergency Service of Ukraine and Ministry of Education |

Biały Słoń (English: White Elephant; Ukrainian: Білий слон, Bily slon) is a Polish name for an abandoned campus of the former Polish Astronomical and Meteorological Observatory of University of Warsaw, located at remote area on the peak of Pip Ivan in the Chornohora range of the Carpathian Mountains, Ukraine. Currently the structure is used as a mountain shelter with a small search and rescue team with some rooms adapted for lodging and recovery.

Along with that Bialy Slon is recognized as a historical landmark and there are restoration activities on the way since 2012 to restore its original conditions in cooperation with the Ciscarpathian National University and the University of Warsaw and scheduled to be finished in 2018.[2] It is considered to be the highest built residential structure in Ukraine.[2]

The closest settlement today is a village of Zelena in Verkhovyna Raion (Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast) and territorially belongs to the Zelena rural council. Currently the observatory is classified under the registration number three as a monument of cultural heritage that is not considered for privatization.[3] The facility is located with the Carpathian National Nature Park.

The region was part of the Second Polish Republic when the observatory was established during the interbellum period. Biały Słoń, started in 1937 and completed in the summer of 1938, was the highest-elevated, permanently inhabited, building in Poland.[4] It was located on the international border between the Second Polish Republic and Czechoslovakia that stretched across mountain peaks of the Carpathian Mountains.

Polish observatory

Preparation and construction

According to Wladyslaw Midowicz, the first and only director of the observatory, the construction of "Biały Słoń" was suggested by a group of influential Warsaw astronomers who managed to convince General Leon Berbecki, director of the influential Airborne and Antigas Defence League, to support it. General Tadeusz Kasprzycki, minister of military affairs, also backed the construction of the observatory.[5]

The building design was approved sometime in 1935.[6] Construction of the building began in the summer of 1936[6] with an official ceremony for the placing of the cornerstone. Biały Słoń was a very expensive structure with total costs exceeding one million Polish złoty, a huge burden on the state budget at the time. The design was based on the Przemyśl Castle and shaped like a letter "L" with a tower.

The whole complex consists of three major features that could be considered as separate structure connected together: a tower, a main building, and smaller service attachment. Biały Słoń had five stories facing the Czechoslovakian side (today Zakarpattia Oblast), and two stories facing the Polish side (today Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast).[6] The whole complex was built mostly from local sandstone.[6] Due to lack of roads, the construction materials were brought by horses, or either by hand or on the backs of local Hutsuls and soldiers of the 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment from the Vorokhta train station located some 70 km (43 mi) away.[6][5] The walls of a lower attachment and the semi-basement floor have a thickness of 1.5 m (4.9 ft), while upper floors - 1 m (3.3 ft).[6] The roof of a building was covered with copper sheets.[6] On the southern side there was a rotunda on which a telescope was located.[6] The copper dome of the telescope opened automatically.[6]

Biały Słoń had 43 rooms, including a conference hall, living quarters, offices, a cafeteria, a battery station, and a boiler room in the basement (the lower structure).[6] The upper floors were occupied by astronomers and meteorologists, most of whom worked for the State Meteorological Institute and Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw. Their work was to carry out meteorological observations for the Polish Air Force. In the lower levels, there were lodgings for soldiers of the "Karpaty" Regiment of the Border Defence Corps, with headquarters in Stryj.[4] Altogether, the number of inhabitants never exceeded 20. Among those who worked there were professor Wlodzimierz Zonn, doctor Jan Gadomski, and professor Eugeniusz Rybka.

Opening and operations

The opening ceremony of the building took place on 29 July 1938.[7] Its official name was the "Observatory of the State Meteorological Institute", but soon it took on the nickname "Biały Słoń", due to the color of its walls. The observatory was lavishly equipped, with a custom-made astrograph and refracting telescope made by the British company Grubb Parsons of Newcastle upon Tyne. It had its own power plant with two diesel motor-generators and central heating fueled by oil, which was transported in iron barrels from the Polmin company in Borysław (today Boryslav). The military authorities also installed their own equipment, including two radiotelephone prototypes constructed to withstand high altitude.

The observatory was located in a remote, deserted area, with the nearest store and mail office 12 miles (19 km) away (at Żabie, today Verkhovyna), the nearest doctor 30 miles (48 km) away, and a rail station in Kolomyia as far as 80 miles (130 km) away. The director of the observatory, Mykulychyn native Władysław Midowicz, wrote that the staff's main problem, however, was water, as no waterworks had been constructed and it had to be carried from a stream 4 miles (6.4 km) away.[5]

For fourteen months (July 1938-September 1939) the observatory was the highest-elevated, permanently inhabited, building in interbellum Poland. As entry was permitted only with a special military pass, local Hutsuls made up several legends about the building and its inhabitants. Wladyslaw Midowicz wrote that the Hutsuls thought that the observatory was in fact a mighty cannon, capable of attacking neighboring countries.[5]

World War II and abandonment

On 18 September 1939, following the Soviet aggression on the eastern part of Poland (see: Kresy), the personnel of the observatory packed the most important equipment (including the refractor) and left for the Hungarian border.[7] At first it was taken to the Budapest Konkoly Observatory, and then the Vienna Observatory by the end of the war.[6] Within the first years after the war, the equipment returned to Poland.[6] The three-lens objective today is located in the Silesian Planetarium (Katowice).[6]

By the end of the month, the Red Army had captured the building. After the region was united with the Ukrainian SSR, the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU) sent an expedition.[6] On 31 December 1939 the first academician-astronomer of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, Oleksandr Orlov, visited the observatory.[6] He established that the most valuable equipment has been taken out of the building, including five large-diameter lenses, two lenses of smaller diameter, two micrometers, and two chronometers.[6] Based on Orlov's report, the NASU Presidium declared that the Carpathian Astronomical Observatory (the newly acquired name) was to be transferred to the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, based on a resolution of the government of the Ukrainian SSR of 2 January 1940.[6] Orlov was appointed the director of the Carpathian Observatory.[6] Until June 1941, it was used as a meteorological station.[6] In the summer of 1941 (see: Operation Barbarossa), the Observatory was seized by the Wehrmacht, which in turn was turned over to the Hungarian troops,[6] who were stationed there until winter 1941. After that, the deserted building became a ruin, even though it had not been damaged during the war. The locals reused all remaining materials;[6] even the cast iron batteries were taken away.[8]

It was reported that Germans took out the metal parts of the astrograph to Lviv.[6] Now they are kept indoors at the Lviv University Faculty of Physics.[6]

Revival

Restoration of the building started only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but progress was very slow. In the mid-1990s scientists of the Lviv Polytechnic, led by professor Anatoliy Dultsev, together with their colleagues from Warsaw Polytechnic, brought forward the idea of rebuilding the observatory. In October 1996 a special conference took place in Lviv and Yaremche, but no works had been started.[7]

On 24 January 2002 another scientific council took place in Yaremche to revive the rebuilding project for the observatory. In the beginning of October 2002 the head of the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast administration, Mykhailo Vyshyvaniuk, sent an official letter to the President of Ukraine, Leonid Kuchma, about the project. By the end of November that year, Vyshyvaniuk received an answer from the First Deputy of the presidential administration, Valeriy Khoroshkovskiy, stating that the proposition was reviewed and recognized as one for international discussion for the restoration. In that regard, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was given the required orders. Between 1998 and 2010 there were about a dozen summer expeditions that contributed to the reconstruction of the building.

In 2012 the Ministry of Culture of Poland directed about $70,000 as a grant program in partnership with the Ciscarpathian University.[1] With contributions from Warsaw and the Ciscarpathian University, the total amount of money allocated for preparation works amounted to $100,000.[6] From July 2012[6] some preparation work started and continued in the fall of 2012, where all window openings were sealed with bricks and the roof was covered.[9][8] It was decided to enclose the building in order to get rid of moisture.[9][10] The whole cost of the project is $2 million.[6] Initially, the project was to be finished by 28 July 2015.[6]

Since at least 2015, there has been a small chapel next to the former observatory complex.[11]

In December 2017 it was reported that the White Elephant will be equipped with a lightning protection system, and the Ciscarpathian University had already ordered documentation for a projected budget.[1] The lightning prevention system was intended to be installed by the summer of 2018.[1]

Mountain rescue post

Since 2015, the building has been home to a mountain rescue post of the Ivano-Frankivsk branch of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine. The post is unique as the most high-altitude government institution in Ukraine. The post is insulated and electrified. There is Wi-Fi and a separate space for visitors.

The tourist traffic over Chornohora Ridge is constant and exceeds 6,000 people per month in summer, according to statistics of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine in 2017. Between the summer of 2016 and summer of 2017, the mountain was visited by 4,000 groups totaling over 22,000 people, of whom 9,000 were foreigners. Some 420 groups totaling about 1,500 people found shelter at the top. The rescue post conducted seven search-and-rescue missions saving eight people, and provided various types of aid to 89 others.

In 2017 a joint Polish-Ukrainian mountain rescue service and a school of mountain rescue were created.[1] During the ongoing restoration activities in 2017, main rooms of mountain shelter were not available, but some provisional space was created without heating.[12]

Gallery

Skiers (1964)

Skiers (1964) Conditions of the actual observatory room in 2006

Conditions of the actual observatory room in 2006 In the evening (2008)

In the evening (2008) Conditions of the top level (2012)

Conditions of the top level (2012) Back side (2012)

Back side (2012) Mountaineers in winter (2012)

Mountaineers in winter (2012) People on the top of the building (2014)

People on the top of the building (2014) Visitors (summer, 2014)

Visitors (summer, 2014) White Elephant in snow (2016)

White Elephant in snow (2016)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White Elephant" in Carpathians will receive a system of lightning protection ("Білий слон" у Карпатах отримає систему громовідведення). Ukrinform. 4 December 2017

- 1 2 Renovation of the abandoned observatory at the Carpathian peak continues. Ukrayinska Pravda. 7 October 2015

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Law of Ukraine: About the list of monuments of cultural heritage that are not considered for privatization (#574-17, September 23, 2008)

- 1 2 (in Polish) Archived 2009-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 (in Polish)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 The abandoned observatory in Carpathians will be rescued. (Закинуту обсерваторію в Карпатах будуть рятувати. ФОТО). Istorychna Pravda (Ukrayinska Pravda). 9 July 2012

- 1 2 3 (in Polish)

- 1 2 "White Elephant" in Carpathians will be restored, and on its roof will be installed solar batteries ("Білий слон" у Карпатах відновлюють, а на даху встановлюють сонячні батареї (ФОТО)). Mukachevo.net. 25 August 2014

- 1 2 (in Ukrainian) http://www.report.if.ua/portal/novyny/na-gori-pip-ivan-pochaly-zamurovuvaty-observatoriyu-foto On the Pip Ivan mountain started to wall up the observatory (На горі Піп Іван почали замуровувати обсерваторію (ФОТО))]. Reporter (Ivano-Frankivsk). 17 September 2012.

- ↑ In the observatory on Pip Ivan have started works in conservation (В обсерваторії на Піп-Івані почалися роботи з консервації. ФОТО). Istorychna Pravda (Ukrayinska Pravda). 5 October 2012

- ↑ The Pip Ivan mountain in Carpathians is covered in snow, while in Mukachevo a lilac blooms (Гору Піп Іван в Карпатах занесло снігом, а в Мукачево цвіте бузок). Mirror Weekly. 10 October 2016

- ↑ White Elephant will help tourists with shelter (Білий слон допоможе туристам з укриттям). Ukrinform. 30 October 2017

External links

- Grand opening of the first stage of restoration of the Astronomical and Meteorological Observatory on Pip Ivan mountain – consecration of a mountain rescue post (УРОЧИСТЕ ВІДКРИТТЯ ПЕРШОЇ ЧЕРГИ ВІДНОВЛЕННЯ АСТРОНОМІЧНО-МЕТЕОРОЛОГІЧНОЇ ОБСЕРВАТОРІЇ НА ГОРІ ПІП ІВАН – посвята рятувального поста гірських рятувальників). State Service of Ukraine on Emergency Situations. 18 September 2017.

- Restoration of the Astronomic Observatory (Відновлення астрономічної обсерваторії). Ciscarpathian Pedagogic University. 25 December 2014

- Pip Ivan (aerial view by quadcopter). YouTube. 2015

- "White Elephant" of the Carpathians - short video dedicated to the Observatory, Polish Institute in Kyiv, 2018.