| Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) | |

|---|---|

| Cree headman | |

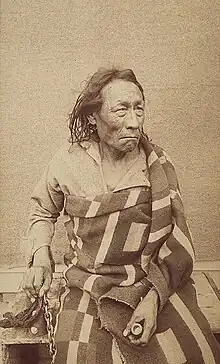

Chief Mistahi-maskwa, 1885 | |

| Born | c. 1825 Jackfish Lake, Rupert’s Land |

| Died | 17 January 1888 Poundmaker Indian Reserve, Cut Knife, Saskatchewan District (Northwest Territories), Canada |

| Father | Black Powder |

| Mother | Delaney |

Big Bear, also known as Mistahi-maskwa (Cree: ᒥᐢᑕᐦᐃᒪᐢᑿ; c. 1825 – 17 January 1888[1]), was a powerful and popular Cree chief who played many pivotal roles in Canadian history. He was appointed to chief of his band at the age of 40 upon the death of his father, Black Powder, under his father's harmonious and inclusive rule which directly impacted his own leadership. Big Bear is most notable for his involvement in Treaty 6 and the 1885 North-West Rebellion; he was one of the few chief leaders who objected to the signing of the treaty with the Canadian government.[2] He felt that signing the treaty would ultimately have devastating effects on his nation as well as other Indigenous nations. This included losing the free nomadic lifestyle that his nation and others were accustomed to. Big Bear also took part in one of the last major battles between the Cree and the Blackfoot nations. He was one of the leaders to lead his people against the last, largest battle on the Canadian Plains.[1]

Early life

Big Bear (Mistahi-maskwa, ᒥᐢᑕᐦᐃᒪᐢᑿ in syllabics) was born in 1825 in Jackfish Lake, near the future site of Battleford. His father, Muckitoo (otherwise known as Black Powder), was a minor chief of a tribe of 80 Plains Cree-Saulteaux people who were deemed to be "true nomadic hunters".[2][3] Little is known about Big Bear's mother. When Big Bear was old enough to walk on his own he spent his time wandering the camp socializing with many people, from the women to council members. In the spring of 1837, smallpox struck Big Bear's community and caused the quick departure of the Cree from the plains. Big Bear was infected with the virus but unlike many in the community, after two months of suffering, he overcame it, although it did leave his face partially disfigured.[4] After his recovery from smallpox, Big Bear began to spend a great deal of time with his father, including a journey by the two of them to Bull's Forehead Hill, where they spent a great deal of time reflecting and offering to their gods and spirits.

Upon reflection, Big Bear was visited by many spirits, but the bear took great prominence in his mind. As a result of his vision of the Bear Spirit, which is the most powerful spirit regarded by the Crees, he received his power bundle, song, and his name.[1] The power bundle, which was never opened unless to be worn in war or dance, contained a fur necklace in the shape of a bear paw.[1][5] It is said that when the weight of the necklace rested against his soul, it enabled him to be in a perfect power position where nothing could hurt him.[1] This necklace was the source of his nickname Maskwa, meaning bear, and Mistahi, meaning much, or big.[6]

It is reported that throughout Big Bear's life, he had several wives, producing at least four male children who would carry on his name, including his son Âyimisîs (Little Bad Man/Little Bear), who helped found the Montana First Nation reserve in Alberta and the Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana.[1] There is little documentation to support the names of most of his sons.

Leadership

Before becoming a great leader, Big Bear became a great warrior, taking warriors under his father's command on missions that he described as "haunting the Blackfoot".[7] Upon the death of his father Black Powder in the winter of 1864, his Band with over 100 members needed a chief. Big Bear was 40 years old and was the obvious choice. He would be the next chief.

Big Bear was described as "an independent spirit" who did not like taking direction from outsiders."[2] He was chosen and followed by the Plains Cree because of his traditional manner and wisdom.

Traditional activities, such as hunting and warfare, kept Big Bear and his band occupied until the 1870s brought police, treaties, and the end of the buffalo.[1]

At the height of his influence in the winter of 1878 to 1879, the buffalo that the plains peoples hunted for food did not come north.[1]

Historical context

The Western Plains Indigenous People underwent a cultural, environmental and structural change starting in the mid-1870s and continuing into the late 1800s. Canada was attempting to cultivate the land that the Indigenous population occupied for European settlers. The treaties were the method of choice by the government to gain rights to the ground; all Indigenous groups were given the opportunity, according to the government, to sign and receive the benefits of the treaty terms. However, the Indigenous People who did not want to sign were ultimately forced to sign because of environmental and cultural changes between 1870 and 1885.[8] The most significant contributing factor to this was the disappearance of the bison which created a region-wide famine; in addition to this, there was the emergence and widespread epidemic of tuberculosis which had a devastating effect on the Indigenous population.[9] The disappearance of the bison has been explained to some extent by the overhunting by white settlers to supply the fur trade which ultimately led to the famine. There were some attempts by the Canadian government to conserve the bison but the measures were not enacted in time to stop the drastic depletion of the bison food supply.[10] In the early 1880s, tuberculosis became the main killer of the Indigenous people on the reserve as European settlers brought over the disease and spread it through coughing and the sharing of pipes during tobacco-smoking ceremonies.[9] The disappearance of the bison was devastating to the Indigenous population because hunting allowed them to be self-sufficient and free from the dominion government; once the bison disappeared their need for assistance was imperative.[11] The Canadian government was the only option of survival but this meant signing the numbered treaties which would change their culture indefinitely. During this time, Big Bear tried to withhold his signature from the treaty so that his people might get better terms but by the mid-1880s malnutrition was severe and the meagre rations given by the dominion government did not supply enough food. Big Bear was ultimately forced to sign the treaty on 8 December 1882 to save his people from starvation and disease because the dominion government would not help unless they signed.[2][12] These factors contributed to the many deaths of Indigenous leaders leaving tribes without their history, which was taught by the elderly, and without men to lead their tribes changing their life from that point on.

Conflict with other Indigenous People

To be a Scrub Plains Cree Indigenous man it was an expectation to be an accomplished hunter and warrior, Big Bear was no exception to the rule. Big Bear was known to be a strong warrior and was often, as an adult, called upon to defend the community. A Cree man, to raise his position in the community, participated in raids and or attacks of enemy tribes which meant stealing of horses, land and food from their enemies. Big Bear's main responsibility was to be a hunter and provide for his family but he was involved in attacks against the enemies of the Cree.[14]

The Battle of the Belly River was one of the largest battles that the Cree were involved in. Occurring in October 1870, Big Bear and his band were involved in an attack between the Plains Cree and their enemies, the Blackfoot tribe, at Belly River, which is near present-day Lethbridge, Alberta.[2] Known to be the largest Indian battle to be fought on the Canadian Plains, the Blackfoot band only lost 40 warriors while the Cree lost between 200 and 300.[1] This was the last battle to be fought between the First Nations.[2] The decades following this battle brought an increased White settlement, as well as police and government presence and the disappearance of the buffalo.[2]

Treaty 6

As the 1870s began, Big Bear and his tribe had reached the high point of development for their band. It started to become more and more apparent that these conditions would not remain forever. Disease had begun to ravage his people and the declining numbers of buffalo threatened their food source and economy.[15] This was quite worrisome for Big Bear as both a father and a chief, and he knew something had to be done. On 14 August 1874, The Hudson's Bay Company visited Big Bear and his fellow Cree people. This was seen as peculiar to Big Bear and his people as the Hudson's Bay Company would have had to travel seven days from the nearest trading post to visit their camp. The Hudson's Bay Company arrived with four wagons full of supplies.[16] Factor William McKay (an old friend of Big Bear) came along for the trip, and he warned Big Bear of the establishment of the North-West Mounted Police in the area. McKay told Big Bear that the North-West Mounted Police were to preserve the west as Canadian and how they were not to interfere with but to protect aboriginal interests.[17] At the end of the visit, McKay and the HBC distributed gifts to the 65 tents of Big Bear's people; however, some were reluctant, they viewed the gifts and the North-West Mounted Police as a means of appeasement and incentive to start the treaty process with Canada.[17]

Big Bear began talks with the Canadian government in the 1870s to work out a treaty. Big Bear was never open to the idea of reserve life, as he feared his loss of freedom and identity as a hunter.[18] But he knew that best way for him and his band to avoid starvation was to sign a treaty with the Canadian government. By 1876, all major Plains Cree chiefs had signed Treaty 6 except for Big Bear. Big Bear stalled signing as he believed that the Canadian government would violate the treaty. Big Bear said "we want none of the Queen's presents: When we set a fox trap we scatter pieces of meat all around but when the fox gets into the trap we knock him on the head. We want no baits. Let your chiefs come like men and talk to us."[19]: 70 Big Bear believed that the Canadian government was telling him and his fellow chiefs what they wanted to hear. This led Big Bear to resist signing and to pursue better terms for Treaty 6.[19]

Big Bear made several attempts to warn the others against signing Treaty 6. At one point Big Bear rode by horseback to each lodge in the area urging people not to sign the treaty and not to give up the land, because it was so rich in natural resources.[19] Big Bear also resisted publicly at both Fort Carleton and Pitt, where the treaty was being signed. Big Bear understood the importance of making the best of this treaty as it would have implications on the generations to come. Big Bear also questioned the Eurocentric worldview and new order being brought forth with these treaties.[19]

Others tried to discredit Big Bear in his attempt to change Treaty 6. John McDougall tried on several occasions to discount him. He claimed Big Bear was an outsider, that he was not of the area and did not deserve the esteem he carried among the people of this area.[19]: 75–6 This was not true, as he was a Cree but also his father was Saulteaux (the other aboriginal group present in the signing of Treaty 6). He was not an outsider but rather leader of a group of people who had elements of both cultures.[19]: 76 Big Bear resisted signing but signed Treaty 6 in 1882. He did so because he believed he had no other choice.[18] Big Bear believed he was betrayed by the other chiefs as they signed the treaty after all his warnings.

The North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion was a five-month revolt in 1885 against the Canadian government that was mainly fought by the Métis and their First Nations allies due to rising fear, insecurity, and white settlers of the rapidly changing West.[20] The result of this battle was seen in the enforcement of Canadian law, the subjugation of the Plains Indigenous Peoples, and the conviction of Louis Riel.[20]

Big Bear's involvement in the North-West Rebellion was seen in his advocacy for a better deal with the Canadian government in terms of Treaty 6. By the late 1870s, the Plains Indigenous nations were facing starvation due to the disappearing bison herds. In 1880, Big Bear and Crowfoot founded a confederacy in order to solve their people's grievances.[20] In 1885, the Canadian government cut off rations to force Big Bear to settle, as he was still resistant in moving his people onto a reserve.[20]

Led by Big Bear's son Little Bad Man and Chief Wandering Spirit, their group camped along Frog Lake believed that they could take matters into their own hands after receiving news that the Métis defeated the North-West Mounted Police at Duck Lake on 26 March 1885.[2] On 1 April 1885, several Métis and non-Métis settlers were taken as prisoners; the following day, Wandering Spirit had killed federal agent Thomas Trueman Quinn, who denied his people food rations.[2] Although Big Bear tried to stop the violence, the warriors went on to kill nine more men.[2] This became known as the Frog Lake Massacre. Once news spread of this incident, the Canadian government decided to hold Big Bear responsible as an active participant in the rebellion, even though at this point he had no control over his band.[2]

Life after Treaty 6 and the Trial of Big Bear

Big Bear had resisted signing Treaty 6 for four years. With food supplies running low and his people facing starvation, he was forced to sign the Treaty.[21] After signing the Treaty, Big Bear and his people could not decide where their reserve would be. Though they did not want to live on a reserve, in order to receive food rations from the government a location needed to be decided on. The first winter after signing the treaty, Big Bear and his people did not receive any rations as they had not decided what reserve to live on. It was in the year 1884 that Big Bear would meet Hudson's Bay Company clerk Henry Ross Halpin in Frog Lake, and the pair soon became friends. [22] In 1885 Big Bear had chosen a reserve to live on. After Big Bear was unable to choose a reserve quickly, he began losing influence over his people. Cree Chief Wandering Spirit rose in authority among the Cree people.[22] When the Métis initiated the North-West Rebellion of 1885 under Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont, Big Bear and his supporters played a minimal role in the overall uprising, Big Bear's son Little Bear joined with Chief Wandering Spirit to go to Frog Lake and kill some of the white residents. Big Bear surrendered to the Mounted Police on 2 July 1885 at Fort Carlton.[20]

Big Bear had tried to solve the problems between his people and the Canadian government peacefully.[23] Many people felt Big Bear would be found 'not guilty' as he had tried to stop the Massacre at Frog Lake and tried to protect those that were taken prisoner. Henry Ross Halpin testified at his trial saying that he was just as much of a prisoner as he, himself had been. At the time of the trial, Big Bear was 60 years old. The trial was confusing for Big Bear as the trial was in English, and had to be translated into Cree. Hugh Dempsey has stated in his book, that Stanley Simpson, a man who was taken prisoner at Fort Pitt, was the only man to appear for the Prosecution. Much of the evidence was in favour of Big Bear's innocence. The evidence was clear that Big Bear had not taken part in killings at Frog Lake or the looting and taking of prisoners at Fort Pitt. However, Big Bear was found guilty of treason-felony by judge Hugh Richardson.[2] He was sentenced to three years at Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba and converted to Christianity during imprisonment.

Death

While imprisoned, Big Bear became ill and was eventually released in February 1887 after serving approximately half of his prison term.[2] He resided on the Little Pine reserve until his failing health conditions resulted in his death on January 17, 1888, at 62 years of age.[2]

Legacy

Long after his death, Big Bear's legacy continues to be prominent to this day. To many, he is remembered as a powerful Cree Chief who advocated for Aboriginal rights and fought against socio-economic injustices that the Canadian government brought upon his people.[2] He was chosen and followed by the Cree because of his wisdom; this can be seen in the fact that he resisted whites with ideas, not guns or any sort of violence.[1]

It has been argued that Big Bear should be commemorated as part of the ongoing reconciliation process towards Indigenous people in Canada, as he deserves public recognition for all that he sacrificed and stood up for during his time as Chief.[24]

The issue of chiefs, such as Big Bear, Poundmaker and One Arrow, remaining convicted for the crime of treason-felony has been brought up in order to exonerate them.[25] It has been said that these convictions were false, as “the government of the day was looking for an excuse to silence First Nations leaders who were pressing for the treaties to be honoured.”[25]

In popular culture

- In the miniseries Big Bear (1998), directed by Gil Cardinal, Big Bear is played by Gordon Tootoosis.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wiebe, Rudy (2003). MISTAHIMASKWA (Big Bear). University of Toronto.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Pannekoek, Frits (2016). "Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ↑ Wiebe 2008, p. 7

- ↑ Wiebe 2008, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Wiebe 2008, p. 14

- ↑ Wiebe 2008, p. 15

- ↑ Wiebe 2008, p. 17

- ↑ Friesen 1987, pp. 148–149

- 1 2 Daschuk 2013, pp. 99–100

- ↑ Friesen 1987, p. 150

- ↑ Daschuk 2013

- ↑ Daschuk 2013, pp. 160–161

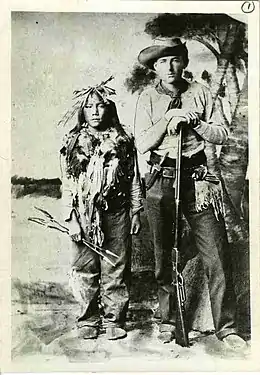

- ↑ "Big Bear Trading at Fort Pitt". Our Legacy. University of Saskatchewan Archives. 1884.

- ↑ Jenish, D'arcy (1999). Indian Fall: The Last Great Days of the Plains Cree and the Blackfoot Confederacy. Toronto, Ontario: Penguin Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-670-88090-4.

- ↑ Miller 1996, p. 58.

- ↑ Miller 1996, p. 59.

- 1 2 Miller 1996, p. 60.

- 1 2 Allard, Jean (2002). "Big Bear's Treaty: The road to freedom". Inroads. 11: 117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McLeod, Neil (1999). "Rethinking Treaty Six in the spirit of Mistah maskwa (Big Bear)" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. XIX: 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Beal, Bob; Macleod, Rod (2006). "North-West Rebellion". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ↑ Dempsey 1984, p. 120

- 1 2 Thompson, Christian (2004). Saskatchewan First Nations: Lives Past and Present. University of Regina. p. 28.

- ↑ Dempsey 1984, p. 122

- ↑ Waiser, Bill (4 October 2020). "A case for commemorating Chief Big Bear: an early advocate for Indigenous rights". CBC. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- 1 2 Warick, Jason (24 May 2019). "Chief Poundmaker exoneration spurs calls for more historical corrections". CBC News. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

Sources

- Daschuk, James (2013). Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. University of Regina Press. ISBN 978-0-88977-296-0.

- Dempsey, Hugh (1984). Big Bear : The End of Freedom. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-88894-506-X.

- Friesen, Gerald (1987). The Canadian Prairies: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6648-0.

- Miller, James Rodger (1996). Big Bear, Mistahimusqua. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-272-4.

- Wiebe, Rudy (2008). Extraordinary Canadians: Big Bear. Penguin Canada. ISBN 978-0-14-317270-3.

Further reading

- Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser. Loyal Till Death: Indians and the North-West Rebellion (1997)

- Rudy Wiebe, The Temptations of Big Bear, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995. ISBN 0-7710-3454-7