| Billfish Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| The largest billfish, the Atlantic blue marlin weighs up to 820 kg (1800 lb) and has been classified as a vulnerable species.[3][2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Clade: | Percomorpha |

| Order: | Istiophoriformes |

| Informal group: | "Xiphioids" |

| Families: | |

| |

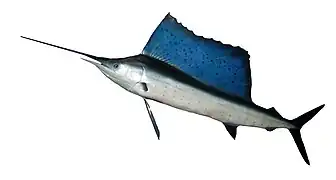

The billfish are a group of saltwater predatory fish characterised by prominent pointed bills (rostra), and by their large size; some are longer than 4 m (13 ft). Extant billfish include sailfish and marlin, which make up the family Istiophoridae; and swordfish, sole member of the family Xiphiidae. They are often apex predators which feed on a wide variety of smaller fish, crustaceans and cephalopods. These two families are sometimes classified as belonging to the order Istiophoriformes, a group which originated around 71 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous, with the two families diverging around 15 million years ago in the Late Miocene.[4] However, they are also classified as being closely related to the mackerels and tuna within the suborder Scombroidei of the order Perciformes.[5] However, the 5th edition of the Fishes of the World does recognise the Istiophoriformes as a valid order, albeit including the Sphyraenidae, the barracudas.[6]

Billfish are pelagic and highly migratory, and are found in all oceans.[7] Although they usually inhabit tropical and subtropical waters, swordfish are also found in temperate waters. Billfish use their long spear/sword-like upper beaks to slash at and stun prey during feeding. Their bills have been known to impale prey, and have sometimes even accidentally impaled boats and people, but they are not intentionally used for this purpose.[8] They are highly valued as game fish by sports fishermen.

Evolution

Several extinct families of smaller billfish are known from the early Paleogene, including the Blochiidae, Palaeorhynchidae, and Hemingwayidae; all of these already have the elongated rostrum present in modern billfish. The earliest fossil billfishes are a Blochius-like fish from Peru and Hemingwaya from Turkmenistan, both of which are known from the Late Paleocene.[9][10][11]

The enigmatic Cylindracanthus, known from the Late Cretaceous to the Eocene, is sometimes considered a "billfish" related to blochiids on the basis of its presumed rostral spines, but no other fossils are known of it aside from its rostral spines, leading to the suggestion that it had a cartilaginous body and may even be a relative of sturgeons.[12] Similarly, the pachycormid fish Protosphyraena and the plethodid fish Rhamphoichthys from the Late Cretaceous had both convergently evolved a highly billfish-like body plan, but are known to be very distantly related to actual billfish; these genera may have instead served as a Cretaceous ecological analogue to billfish.[13]

Species

The term billfish refers to the fishes of the families Xiphiidae and Istiophoridae. These large fishes are "characterized by the prolongation of the upper jaw, much beyond the lower jaw into a long rostrum which is flat and sword-like (swordfish) or rounded and spear-like (sailfishes, spearfishes, and marlins)."[14]

True billfish

The 12 species of true billfish are divided into two families and five genera. One family, Xiphiidae, contains only one species, the swordfish Xiphias gladius, and the other family, Istiophoridae, contains 11 species in four genera, including marlin, spearfish, and sailfish.[14][15] Controversy exists about whether the Indo-Pacific blue marlin, Makaira mazara, is the same species as the Atlantic blue marlin, M. nigricans. FishBase follows Nakamura (1985)[14] in recognizing M. mazara as a distinct species, "chiefly because of differences in the pattern of the lateral line system".[16]

| Family | Genus | Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiphiidae | Xiphias | Swordfish | Xiphias gladius (Linnaeus, 1758) | 455 cm | 300 cm | 650 kg | years | 4.49 | [17] | [18] | |

| Istiophoridae | Istiophorus Sailfish |

Atlantic sailfish | Istiophorus albicans (Latreille, 1804) | 315 cm | cm | 58.1 kg | 17 years[20] | 4.50 | [21] | Not assessed | |

| Indo-Pacific sailfish | Istiophorus platypterus (Shaw, 1792) | 340 cm | cm | 100 kg | years | 4.50 | [22] | [23] | |||

| Istiompax | Black marlin | Istiompax indica (Cuvier, 1832) | 465 cm | 380 cm | 750 kg | years | 4.50 | [15] | |||

| Makaira | Indo-Pacific blue marlin | Makaira mazara (Jordan and Snyder, 1901) | 500 cm | 350 cm | 625 kg | 4.5 – 6 years | 4.46 | [16] | |||

| Atlantic blue marlin | Makaira nigricans (Lacépède, 1802) | 500 cm | 290 cm | 820 kg | years | 4.50 | [27] | ||||

| Tetrapturus | White marlin | Tetrapturus albidus/Kajikia albida Poey, 1860 | 300 cm | 210 cm | 82.5 kg | years | 4.48 | [28] | |||

| Shortbill spearfish | Tetrapturus angustirostris Tanaka, 1915 | 200 cm | cm | 52 kg | years | 4.50 | [30] | ||||

| Striped marlin | Tetrapturus audax/Kajikia audax (Philippi, 1887) | 350 cm | cm | 200 kg | years | 4.58 | [32] | [33] | |||

| Roundscale spearfish | Tetrapturus georgii Lowe, 1841 | 184 cm | cm | 24 kg | years | 4.37 | [35] | ||||

| Mediterranean spearfish | Tetrapturus belone Rafinesque, 1810 | 240 cm | 200 cm | 70 kg | years | 4.50 | [37] | ||||

| Longbill spearfish | Tetrapturus pfluegeri Robins and de Sylva, 1963 | 254 cm | 165 cm | 58 kg | years | 4.28 | [39] |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

Swordfish, most commercially fished billfish

Swordfish, most commercially fished billfish The Indo-Pacific sailfish, fastest of all fishes

The Indo-Pacific sailfish, fastest of all fishes

Billfish-like fish

A number of other fishes have pronounced bills or beaks, and are sometimes referred to as billfish, despite not being true billfish. Halfbeaks look somewhat like miniature billfish, and the sawfish and sawshark, which are cartilaginous fishes with long, serrated rostrums. Needlefish are sometimes confused with billfish, but they are "easily distinguished from the true billfish by having both jaws prolonged, the dorsal and anal fins both single and similar in size and shape, and the pelvic fins inserted far behind the pectorals."[14] Paddlefish have elongated rostrums containing electroreceptors that can detect weak electrical fields. Paddlefish are filter feeders and may use their rostrum to detect zooplankton.[41]

Structure and function of the bill

Billfish have a long, bony, spear-shaped bill, sometimes called a snout, beak or rostrum. The swordfish has the longest bill, about one-third its body length. Like a true sword, it is smooth, flat, pointed and sharp. The bills of other billfish are shorter and rounder, more like spears.[42]

Billfish normally use their bills to slash at schooling fish. They swim through the fish school at high speed, slashing left and right, and then circle back to eat the fish they stunned. Adult swordfish have no teeth, and other billfish have only small file-like teeth. They swallow their catch whole, head-first. Billfish do not normally spear with their bills, though occasionally a marlin will flip a fish into the air and bayonet it. Given the speed and power of these fish, when they do spear things the results can be dramatic. Predators of billfish, such as great white and mako sharks, have been found with billfish spears embedded in them.[43][44][45] Pelagic fish generally are fascinated by floating objects, and congregate about them.[46] Billfish can accidentally impale boats and other floating objects when they pursue the small fish that aggregate around them.[45] Care is needed when attempting to land a hooked billfish. Many fisherman have been injured, some seriously, by a billfish thrashing its bill about.[44]

Other characteristics

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Billfish are large swift predators which spend most of their time in the epipelagic zone of the open ocean. They feed voraciously on smaller pelagic fish, crustaceans and small squid. Some billfish species also hunt demersal fish on the seafloor, while others descend periodically to mesopelagic depths. They may come closer to the coast when they spawn in the summer. Their eggs and larvae are pelagic, that is they float freely in the water column.[43][45] Many grow over three metres (10 feet) long, and the blue marlin can grow to five metres (16 feet). Females are usually larger than males.[43][45]

Like scombroids (tuna, bonito and mackerel), billfish have both the ability to migrate over long distances, efficiently cruising at slow speeds, and the ability to generate rapid bursts of speed. These speed bursts can be quite astonishing, and the Indo-Pacific sailfish has been recorded making a burst of 68 miles per hour (110 km/h), nearly top speed for a cheetah and the highest speed ever recorded for a fish.[43]

Some billfish also descend to considerable mesopelagic depths. They have sophisticated swim bladders which allow them to rapidly compensate for pressure changes as the depth changes. This means that when they are swimming deep, they can return swiftly to the surface without problems.[47] "Like the large tuna, some billfish maintain their body temperature several degrees above ambient water temperatures; this elevated body temperature increases the efficiency of the swimming muscles, especially during excursions into the cold water below the thermocline."[45] See heater cells for more information about these specialized modified muscle cells.[48]

In 1936 the British zoologist James Gray posed a conundrum which has come to be known as Gray's paradox. The problem he posed was how dolphins can swim and accelerate so fast when it seemed their muscles lacked the needed power.[49] If this is a problem with dolphins it is an even greater problem with billfish such as swordfish, which swim and accelerate faster than dolphins. In 2009, Taiwanese researchers from the National Chung Hsing University introduced new concepts of "kidnapped airfoils and circulating horsepower" to explain the swimming capabilities of swordfish. The researchers claim this analysis also "solves the perplexity of dolphin's Gray paradox". They also assert that swordfish "use sensitive rostrum/lateral-line sensors to detect upcoming/ambient water pressure and attain the best attack angle to capture the body lift power aided by the forward-biased dorsal fin to compensate for most of the water resistance power."[50]

Billfish have prominent dorsal fins. Like tuna, mackerel and other scombroids, billfish streamline themselves by retracting their dorsal fins into a groove in their body when they swim.[43] The shape, size, position and colour of the dorsal fin varies with the type of billfish, and can be a simple way to identify a billfish species. For example, the white marlin has a dorsal fin with a curved front edge and is covered with black spots. The huge dorsal fin, or sail of the sailfish is kept retracted most of the time. Sailfish raise them if they want to herd a school of small fish, and also after periods of high activity, presumably to cool down.[43][51]

Distribution and migration

Billfish occur worldwide in temperate and tropical waters. They are highly migratory oceanic fish, spending much of their time in the epipelagic zone of international water following major ocean currents.[43][45] Migrations are linked to seasonal patterns of sea surface temperatures.[52] They are sometimes referred to as "rare event species" because the areas they roam over in the open seas are so large that researchers have difficulty locating them. Little is known about their movements and life histories, so assessing how they can be sustainably managed is not easy.[53][54]

Unlike coastal fish, billfish usually avoid inshore waters unless there is a deep dropoff close to the land.[44] Instead, they swim along the edge of the continental shelf where cold nutrient rich upwellings can fuel large schools of forage fish. Billfish can be found here, cruising and feeding "above the craggy bottom like hawks soaring along a ridge line".[55]

Commercial fishing

In parts of the Pacific and Indian ocean such as the Maldives, billfishing, particularly for swordfish, is an important component of subsistence fishing.

Recreational fishing

Over the years, billfish tournaments have transformed into big business enterprises. Many prestigious tournaments now have enormous calcuttas and purses as well as large numbers of participating anglers. With huge purses and egos on the line, concern often arises whether all participants are adhering to the letter of the rules.

– IGFA Conservation Director, Jason Schratwieser[57]

Billfish are among the most coveted of big gamefish, and major recreational fisheries cater to the demand.[54] In North America, "the apex of the salt water pursuits is billfishing, the quest for elusive blue marlin and sailfish in the deep blue water about 60 miles out."[55] A lot of resources are committed to the activity, particularly in the construction of private and charter billfishing boats to participate in the billfishing tournament circuit. These are expensive purpose-built offshore vessels with powerfully driven deep sea hulls. They are often built to luxury standards and equipped with many technologies to ease the life of the deep sea recreational fisherman, including outriggers, flying bridges and fighting chairs, and state of the art fishfinders and navigation electronics.[55]

The boats cruise along the edge of the continental shelf where billfish can be found down to 200 metres (600 ft), sometimes near weed lines at the surface and submarine canyons and ridges deeper down. Commercial fishermen usually use drift nets or longlines to catch billfish, but recreational fishermen usually drift with bait fish or troll a bait or lure. Billfish are caught deeper down the water column by drifting with live bait fish such as ballyhoo, striped mullet or bonito. Alternatively, they can be caught by trolling at the surface with dead bait or trolling lures designed to imitate bait fish.[58]

Most recreational fishermen now tag and release billfish.[55] A 2003 study surveyed 317,000 billfish known to have been tagged and released since 1954. Of these, 4122 were recovered. The study concluded that, while tag and release programs have limitations, they provided important information about billfish that cannot currently be obtained by other methods.[45][54]

Hooked striped marlin

Hooked striped marlin Hooked billfish can leap spectacularly out of the water

Hooked billfish can leap spectacularly out of the water

As food

Billfish make good eating fish, and are high in omega-3 oils. Blue marlin has a particularly high oil content.[59]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 144 kJ (34 kcal) |

6.65 g | |

19.66 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A | 120 IU |

| Vitamin D | 93% 558 IU |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 5 mg |

| Iron | 3% 0.38 mg |

| Magnesium | 8% 29 mg |

| Phosphorus | 36% 255 mg |

| Potassium | 9% 418 mg |

| Sodium | 5% 81 mg |

| Zinc | 7% 0.66 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 73.38 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Billfish are primarily marketed in Japan, where they are eaten raw as sashimi. They are marketed fresh, frozen, canned, cooked and smoked.[45] It is not usually a good idea to fry billfish. Swordfish and marlin are best grilled or broiled, or eaten raw as in sashimi. Sailfish and spearfish are somewhat tough and are better cooked over charcoal or smoked.[59]

Swordfish auction in the fish market of Vigo

Swordfish auction in the fish market of Vigo Slice of Atlantic blue marlin

Slice of Atlantic blue marlin Swordfish marinade

Swordfish marinade Fried sailfish with noodle salad

Fried sailfish with noodle salad

Mercury

However, because billfish have high trophic levels, near the top of the food web, they also contain significant levels of mercury and other toxins. According to the United States Food and Drug Administration, swordfish is one of four fishes, along with tilefish, shark, and king mackerel, that children and pregnant women should avoid due to high levels of methylmercury found in these fish and the consequent risk of mercury poisoning.[60] [61]

Conservation

Billfish are exploited both as food and as fish. Marlin and sailfish are eaten in many parts of the world, and many sport fisheries target these species. Swordfish are subject to particularly intense fisheries pressures, and although their survival is not threatened worldwide, they are now comparatively rare in many places where once they were abundant. The istiophorid billfishes (marlin and spearfish) also suffer from intense fishing pressures. High mortality levels occur when they are caught incidentally by longline fisheries targeting other fish.[62] Overfishing continues to "push these declines further in some species".[63] Because of these concerns about declining populations, sport fishermen and conservationists now work together to gather information on billfish stocks and implement programs such as catch and release, where fish are returned to the sea after they have been caught. However, the process of catching them can leave them too traumatised to recover.[43] Studies have shown that circle fishing hooks do much less damage to billfish than the traditional J-hooks, yet they are at just as effective for catching billfish. This is good for conservation, since it improves survival rates after release.[64][65]

The stocks for individual species in billfish longline fisheries can "boom and bust" in linked and compensatory ways. For example, the Atlantic catch of blue marlin declined in the 1960s. This was accompanied by an increase in sailfish catch. The sailfish catch then declined from the end of the 1970s to the end of the 1980s, compensated by an increase in swordfish catch. As a result, overall billfish catches remained fairly stable.[66]

"Many of the world's fisheries operate in a data poor environment that precludes predictions about how different management actions will affect individual species and the ecosystem as a whole."[67] In recently years pop-up satellite archival tags have been used to monitor billfish. The capability of these tags to recover useful data is improving, and their use should result in more accurate stock assessments.[68] In 2011, a group of researchers claimed they have, for the first time, standardized all available data about scombrids and billfishes so it is in a form suitable for assessing threats to these species. The synthesis shows that those species which combine a long life with a high economic value, such as the Atlantic blue marlin and the white marlin, are generally threatened. The combination puts such species in "double jeopardy".[69]

See also

References

- Makaira nigricans Archived 29 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine bioSearch. Updated: 20 January 2011.

- 1 2 Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Cardenas, G.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr.; N.; Di Natale, A.; Die, D.; Fox, W.; Fredou, F.L.; Graves, J.; Guzman-Mora, A.; Viera Hazin, F.H.; Hinton, M.; Juan Jorda, M.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Montano Cruz, R.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; Restrepo, V.; Salas, E.; Schaefer, K.; Schratwieser, J.; Serra, R.; Sun, C.; Teixeira Lessa, R.P.; Pires Ferreira Travassos, P.E.; Uozumi, Y.; Yanez, E. (2011). "Makaira nigricans". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170314A6743776. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170314A6743776.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Makaira nigricans Archived 29 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine bioSearch. Updated: 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Santini, F.; Sorenson, L. (2013). "First molecular timetree of billfishes (Istiophoriformes: Acanthomorpha) shows a Late Miocene radiation of marlins and allies". Italian Journal of Zoology. 80 (4): 481–489. doi:10.1080/11250003.2013.848945. S2CID 83901839.

- ↑ Joseph S. Nelson (2006). Fishes of the World (PDF). John Wiley & Sons Limited. pp. 430–434. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- ↑ Nelson, JS; Grande, TC & Wilson, MVH (2016). "Classification of fishes from Fishes of the World 5th Edition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ Ken Schultz: Ken Schultz's Fishing Encyclopedia. 1999. "http://www.gofishn.com/content/billfish# Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine"

- ↑ "Sea Wonder: Swordfish". National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ Friedman, Matt; V. Andrews, James; Saad, Hadeel; El-Sayed, Sanaa (16 June 2023). "The Cretaceous–Paleogene transition in spiny-rayed fishes: surveying "Patterson's Gap" in the acanthomorph skeletal record André Dumont medalist lecture 2018". Geologica Belgica. doi:10.20341/gb.2023.002. ISSN 1374-8505.

- ↑ Monsch, Kenneth A.; Bannikov, Alexandre F. (2011). "New taxonomic synopses and revision of the scombroid fishes (Scombroidei, Perciformes), including billfishes, from the Cenozoic of territories of the former USSR". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 102 (4): 253–300. Bibcode:2011EESTR.102..253M. doi:10.1017/S1755691011010085. ISSN 1755-6910. S2CID 129577132.

- ↑ Fierstine, Harry L. (1 November 2006). "Fossil history of billfishes (Xiphioidei)". Bulletin of Marine Science. 79 (3): 433–453.

- ↑ Parris, D. C., Grandstaff, B. S. and Bell, G. L. 2001. Reassessment of the affinities of the extinct genus Cylindracanthus (Osteichthyes). Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science, 80: 161–172.

- ↑ El Hossny, Tamara; Cavin, Lionel; Kaplan, Ulrich; Schwermann, Achim H.; Samankassou, Elias; Friedman, Matt (2023). "The first articulated skeletons of enigmatic Late Cretaceous billfish-like actinopterygians". Royal Society Open Science. 10 (12). doi:10.1098/rsos.231296. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 10698480. PMID 38077217.

- 1 2 3 4 Nakamura, Izumi (1985) Billfishes of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of marlins, sailfishes, spearfishes and swordfishes known to date FAO Fisheries Synopsis, 125 (5). Rome.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2013). "Istiompax indica" in FishBase. April 2013 version.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Makaira mazara" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Xiphias gladius" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Xiphias gladius (Linnaeus, 1758) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Collette B; et al. (2011). "Xiphias gladius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Arocha F and Ortiz M (2006) Description of Sailfish (SAI) ICCAT Manual.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Istiophorus albicans" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Istiophorus platypterus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Istiophorus platypterus (Shaw, 1792) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Cardenas, G.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr.; N.; Di Natale, A.; Die, D.; Fox, W.; Fredou, F.L.; Graves, J.; Guzman-Mora, A.; Viera Hazin, F.H.; Hinton, M.; Juan Jorda, M.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Montano Cruz, R.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; Restrepo, V.; Salas, E.; Schaefer, K.; Schratwieser, J.; Serra, R.; Sun, C.; Teixeira Lessa, R.P.; Pires Ferreira Travassos, P.E.; Uozumi, Y.; Yanez, E. (2011). "Istiophorus platypterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170338A6754507. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170338A6754507.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Carpenter, K.E.; Di Natale, A.; Fox, W.; Miyabe, N.; Montano Cruz, R.; Nelson, R.; Schaefer, K.; Serra, R.; Sun, C.; Uozumi, Y.; Yanez, E. (2011). "Istiompax indica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170312A6742465. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170312A6742465.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Makaira nigricans" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus albidus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Amorim, A.F.; Bizsel, K.; Boustany, A.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr.; N.; Die, D.; Fox, W.; Fredou, F.L.; Graves, J.; Viera Hazin, F.H.; Hinton, M.; Juan Jorda, M.; Masuti, E.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; Restrepo, V.; Schratwieser, J.; Teixeira Lessa, R.P.; Pires Ferreira Travassos, P.E. (2011). "Kajikia albida". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170322A6747343. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170322A6747343.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus angustirostris" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Carpenter, K.E.; Di Natale, A.; Fox, W.; Miyabe, N.; Montano Cruz, R.; Nelson, R.; Schaefer, K.; Serra, R.; Sun, C.; Uozumi, Y.; Yanez, E. (2011). "Tetrapturus angustirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170315A6744759. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170315A6744759.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus audax" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Tetrapturus audax (Philippi, 1887) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Boustany, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; Cardenas, G.; Carpenter, K.E.; Di Natale, A.; Die, D.; Fox, W.; Graves, J.; Hinton, M.; Juan Jorda, M.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Montano Cruz, R.; Nelson, R.; Restrepo, V.; Schaefer, K.; Schratwieser, J.; Serra, R.; Sun, C.; Uozumi, Y.; Yanez, E. (2011). "Kajikia audax". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170309A6738801. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170309A6738801.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus georgii" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr.; N.; Fox, W.; Fredou, F.L.; Graves, J.; Viera Hazin, F.H.; Juan Jorda, M.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; Teixeira Lessa, R.P.; Pires Ferreira Travassos, P.E. (2011). "Tetrapturus georgii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170333A6752763. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170333A6752763.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus belone" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Heessen, H. (2015). "Tetrapturus belone". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T170334A48680954. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-1.RLTS.T170334A48680954.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Tetrapturus pfluegeri" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- ↑ Collette, B.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; Carpenter, K.E.; de Oliveira Leite Jr.; N.; Fox, W.; Fredou, F.L.; Graves, J.; Viera Hazin, F.H.; Juan Jorda, M.; Minte Vera, C.; Miyabe, N.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; Teixeira Lessa, R.P.; Pires Ferreira Travassos, P.E. (2011). "Tetrapturus pfluegeri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170307A6738137. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170307A6738137.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Wiley, Edward G. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ↑ Schultz 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Aquatic Life of the World pp. 332–333, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2000. ISBN 9780761471707.

- 1 2 3 Iversen ES and Skinner RH (2006) Dangerous sea life of the west Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico: a guide for accident prevention and first aid Page 77–78, Pineapple Press. ISBN 9781561643707.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heemstra PC and Heemstra E (2004) Coastal fishes of Southern Africa Page 424, NISC. ISBN 9781920033019.

- ↑ Hunter JR, Mitchell CT (1966). "Association of fishes with flotsam in the offshore waters of Central America". Fishery Bulletin. 66: 13–29.

- ↑ Schultz, 2007, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Sherwood, Klandorf, Yancey, Animal Physiology: From Genes to Organisms, 2nd edition)

- ↑ Gray, J (1936). "Studies in animal locomotion VI. The propulsive powers of the dolphin". Journal of Experimental Biology. 13: 192–199. doi:10.1242/jeb.13.2.192.

- ↑ Lee, Hsing-Juin; Jong, Yow-Jeng; Change, Li-Min & Wu, Wen-Lin (2009). "Propulsion Strategy Analysis of High-Speed Swordfish". Transactions of the Japan Society for Aeronautical and Space Sciences. 52 (175): 11–20. Bibcode:2009JSAST..52...11L. doi:10.2322/tjsass.52.11.

- ↑ Dement J Species Spotlight: Atlantic Sailfish (Istiophorus albicans) Archived 17 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine littoralsociety.org. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Breman, Joe (2002) Marine geography: GIS for the oceans and seas Page 46, ESRI. ISBN 9781589480452.

- ↑ Lutcavage, M (2001). "Bluefin Spawning in Central North Atlantic" (PDF). Pelagic Fisheries Research Program. 6 (2): 1–6.

- 1 2 3 Ortiz M, Prince ED, Serafy JE, Holts DB, Davy KB, Pepperell JG, Lowry MB, Holdsworth JC (2003). "Global overview of the major constituent-based billfish tagging programs and their results since 1954" (PDF). Marine and Freshwater Research. 54 (4): 489–507. doi:10.1071/MF02028. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Janiskee RL (2008) Tourism and recreation in the Carolinas In: DG Bennett and JC Patton, A geography of the Carolinas, pp. 201–202, Parkway Publishers. ISBN 9781933251431.

- ↑ Based on data sourced from FAO Species Fact Sheets

- ↑ IGFA’s Observer Training Class in Virginia Beach IGFA News, March 2010.

- ↑ Williams RG and Nichols CR (2009) Encyclopedia of Marine Science Page 505, Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438118819.

- 1 2 Livingston AD (1996) Complete Fish & Game Cookbook Page 158, Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811704281.

- ↑ FDA (1990–2010). "Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Natural Resources Defense Council. "Protect Yourself and Your Family". Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ Myers, Ransom A. & Boris Worm (2003). "Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities". Nature. 423 (6937): 280–283. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..280M. doi:10.1038/nature01610. PMID 12748640. S2CID 2392394.

- ↑ ICCAT (2002) Report of the 2001 billfish species group session. ICCAT Collected Volume of Scientific Papers 54: 649–764

- ↑ Prince ED, Ortiz M, and Venizelos A (2002) "A Comparison of Circle Hook and "J" Hook Performance in Recreational Catch-and-Release Fisheries for Billfish" Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine American Fisheries Society Symposium 30: pp. xxx–xxx.

- ↑ Prince ED, Snodgrass D, Orbesen ES (2007). "Circle hooks,'J' hooks and drop‐back time: a hook performance study of the south Florida recreational live‐bait fishery for sailfish, Istiophorus platypterus" (PDF). Fisheries Management and Ecology. 14 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2400.2007.00539.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ↑ Duffy, J. Emmett (2008) Marine biodiversity and food security Encyclopedia of Earth. Updated 25 July 2008.

- ↑ Richardson DE (2008) "Physical and biological characteristics of billfish spawning habitat in the Straits of Florida" Open Access Dissertations. Paper 26.

- ↑ Kerstetter DW, Luckhurst BE, Prince ED, Graves JE (2003). "Use of pop-up satellite archival tags to demonstrate survival of blue marlin (Makaira nigricans) released from pelagic longline gear" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 101: 939–948. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Collette, BB; Carpenter, KE; et al. (2011). "High Value and Long Life—Double Jeopardy for Tunas and Billfishes" (PDF). Science. 333 (6040): 291–292. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..291C. doi:10.1126/science.1208730. PMID 21737699. S2CID 20406751.

Further reading

- Abascal, FJ; Mejuto, J; Quintans, M; Ramos-Cartelle, A (2010). "Horizontal and vertical movements of swordfish in the Southeast Pacific". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 67 (3): 466–474. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp252.

- Eliason, Erika (2010). "Billfishes are closely related to flatfish" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (17): iv. doi:10.1242/jeb.036673.

- Fierstine, Harry L (2006). "Fossil history of billfishes (Xiphioidei)". Bulletin of Marine Science. 79 (3): 433–453.

- Kerstetter, DW; Graves, JE (2007). "Post-release survival of sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus) captured on commercial pelagic longline gear in the southern Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). ICCAT. 60 (5): 1576–1581.

- Little, AG; Lougheed, SC; Moyes, CD (2010). "Evolutionary affinity of billfishes (Xiphiidae and Istiophoridae) and flatfishes (Plueronectiformes): Independent and trans-subordinal origins of endothermy in teleost fishes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (3): 897–904. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.04.022. PMID 20416385.

- Liu, Qing-ping; Ren, Lu-quan; Chen, Kun; Liao, Geng-hua; Yang, Ying; Li, Jian-qiao; Han, Zhi-wu (2010). "Propulsion Experimental Research on the Structure of Swordfish's Lunate Caudal Fin". Advances in Natural Science. 3 (2): 199–205.

- Lynch PD, Graves JE and Latour RJ (2011) "Challenges in the assessment and management of highly migratory bycatch species: a case study of the Atlantic marlins" In: WA Taylor, AJ Lynch and M Schechter (Eds.), Sustainable Fisheries: Multi-level Approaches to a Global Problem, American Fisheries Society. ISBN 978-1-934874-21-9. Review

- Maguire, Jean-Jacques (2006) The state of world highly migratory, straddling and other high seas fishery resources and associated species Fisheries technical paper 495, FAO, Rome. ISBN 9789251055540.

- Reygondeau, G; Maury, O; Beaugrand, G; Fromentin, JM; Fonteneau, A; Cury, P (2011). "Biogeography of tuna and billfish communities" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 39 (1): 114–129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02582.x. S2CID 73646012.

- Schultz, Ken (2011) Ken Schultz's Field Guide to Saltwater Fish John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9781118039885.

- Stobutzki I, Lawrence E, Bensley N and Norris W (2006) "Bycatch mitigation approaches in Australia's Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery: seabirds, turtles, marine mammals, sharks and non-target fish" Information Paper WCPFC-SC2/EBSWG–IP5. Ecosystem and Bycatch Specialist Working Group of the Second Meeting of the Scientific Committee of the WCPFC.

- Takahashi, Taiga (2011). "Left Out at Sea: Highly Migratory Fish and the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). California Law Review. 99 (1): 179–233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Ward P and Hindmarsh S (2006) "An overview of historical changes in the fishing gear and practices of pelagic longliners" WCPFC Scientific Committee, Second Regular Session.

- Wueringer, BE; Squire, L; Kajiura, SM; Hart, NS; Collin, SP (2012). "The function of the sawfish's saw". Current Biology. 22 (5): R150–R151. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.055. PMID 22401891.

External links

- Atlas of Tuna and Billfish Catches Interactive Atlas, FAO, Rome.

- Family Istiophoridae at Fishbase.org

- Family Xiphiidae at Fishbase.org

- The Billfish Foundation

- PBS/BBC/NHK Documentary Superfish

- Bill Fish Outdoor Lodge.

- One Quarter of Tuna and Billfish Fishstocks in Need of Conservation Fish Channel, 26 July 2011.

- Swordfish & Billfish WWF.

- Offield Center for Billfish Studies

- Eastern Tuna And Billfish Fishery Management The FishSite, June 2011.

- Billfish Tagging Tuna Research and Conservation Center.

- Scientists find tuna and billfish species at risk European Commission, 12 September 2011.

- One Quarter of Tuna and Billfish Fishstocks in Need of Conservation Fish Channel, 26 July 2011.

- Blue marlin blues: Loss of dissolved oxygen in oceans squeezes billfish habitat EurekAlert, 14 December 2011.

- Expanding Dead Zones Are Shrinking Tropical Blue Marlin Habitat ScienceDaily, 12 December 2011.

- Study helps assess global status of tuna and billfish stocks EurekAlert, 15 August 2011.

- Assessing Global Status of Tuna and Billfish Stocks ScienceDaily, 15 August 2011.

- Campaign on mercury levels sparks controversy Tico Times, 20 May 2011.

.png.webp)