Black Canadians have lived in New Brunswick since at least the 1690s.[1] As of 2021, there were 12,100 Black residents in New Brunswick, making them the largest visible minority group in the province.[2][3]

History

About 3,300 black loyalists arrived in the province in the mid-1780s, following the American Revolutionary War. They had been promised land grants in exchange for their service in the British army. Given either poor land or no land at all, most left for Sierra Leone.[4]

An additional wave of 371 African-American refugees arrived in 1815, following the War of 1812.[4]

The first human rights protest in New Brunswick occurred in 1916, when most of Saint John's Black community took part in protests over the showing of the controversial American movie The Birth of a Nation.[5] The spiritual heart of Saint John's Black community was the St. Philips African Methodist Episcopalian Church, which was demolished in 1942.[1]

In 1935, Eldridge "Gus" Eatman, a black man from Saint John tried to raise an Ethiopian Foreign Legion to fight for Ethiopia, which was threatened with an invasion by Italy.[6] Eatman's call to defend Ethiopia drew an enthusiastic response to defend what the black lawyer Joseph Spencer-Pitt called "the last sovereign state belonging to the coloured race".[6] However, it appears that no volunteers actually reached Ethiopia.[6]

Since the immigration reforms of the 1970s, the province's multi-generational Black community has been joined by immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa. Some of the larger groups include Jamaicans, people from Democratic Republic of the Congo,[lower-alpha 1] Haitians, and Nigerians.[7] Meanwhile, many from New Brunswick's long established Black communities have moved out of the province. Bangor, Maine's lumber industry in particular attracted Black people from New Brunswick for decades. They formed a sizeable community on the town's west end throughout the 1900s.[8]

The term Africadia was coined by George Elliott Clarke in the 1990s to refer to the combined group identity of African Canadian communities from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.[9]

New Brunswick Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The New Brunswick Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NBAACP) was established in 1959, which followed the Saint John Association for the Advancement of Colored People (SJAACP), which was founded in September 1949.[10] One of the founding members was Frederick Hodges, who held the distinction of being the New Brunswick Federation of Labor's first black officer and the Saint John City Council's first visible minority.[11]

In May 1964, Joseph Drummond, who served as the NBAACP vice president, organized a sit-in at a local barber shop along with two other members, in order to protest against the refusal of service towards colored people in Saint John's barber shops. Additionally, they sought to address the difficulties faced by people of color in achieving fair housing and employment opportunities.[12]

21st century

In May 2021, Kassim Doumbia was elected mayor of Shippagan, New Brunswick, making him the first Black mayor in the province's history.[13]

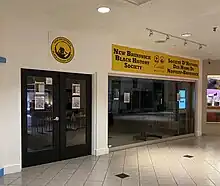

In June 2021, the first permanent display dedicated to the preservation of New Brunswick's Black history opened in Saint John.[14] The opening of the New Brunswick Black History Society follows the opening of similar institutions such as the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia and the Amherstburg Freedom Museum in Ontario.

Settlements

As in many Canadian provinces, independent rural all-Black settlements existed in New Brunswick since the 1800s. Two prominent settlements in New Brunswick were Willow Grove and Elm Hill. As of 2022, only the settlement of Elm Hill remains.[15] The residents of Willow Grove are noted to be settled on extremely infertile land, where very little agriculture was possible. Commerce and industry was also difficult in Willow Grove due to the remoteness of the area from major cities at a time where most lacked access to vehicles or public transit. It was largely depopulated by the 1970s, when most young people chose to relocate to Saint John in search of a better range of opportunities.[16] Woodstock and Kingsclear both had significant Black communities until the 1970s.[17][18]

Today, over 75% of New Brunswick's Black population lives in one of three cities: Moncton, Saint John, or Fredericton.[2] The Indigenous Black Canadian population is heavily concentrated in Saint John, while the other two cities have attracted a growing immigrant African and Caribbean population.[19]

Notable people

- Measha Brueggergosman, opera singer

- Lawrence Costello, police officer killed in the 2018 Fredericton shooting

- Anna Minerva Henderson, teacher, civil servant and poet

- Manny McIntyre, professional baseball and ice hockey player

- Willie O'Ree, first Black player in the National Hockey League (NHL)

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Statistics Canada, for the period 2011-2016, there were 155 immigrants from the DRC, in comparison to just ten from the Republic of the Congo, who were resident in New Brunswick.[lower-alpha 2]

- Government of Canada; Statistics Canada (25 October 2017). "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables - Immigrant population by place of birth, period of immigration, 2016 counts, both sexes, age (total), New Brunswick, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". www12.statcan.gc.ca (in English and French). Retrieved 7 April 2022.

References

- 1 2 Spray, W. A (1972). The Blacks in New Brunswick. Brunswick Press.

- 1 2 "Statistics Canada - New Brunswick". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-02-09). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- 1 2 "Before Willie O'Ree: New Brunswick's surprising black history contributions". CBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "April 1916: First Human Rights Protest in New Brunswick History". NBBHS. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 Panneton, Daniel (16 February 2021). "Forgotten native son: The Canadian who tried to raise an army for Ethiopia". TVO. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ↑ Government of Canada; Statistics Canada (25 October 2017). "Admission Category and Applicant Type (7), Period of Immigration (7), Place of Birth (272), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Immigrant Population Who Landed Between 1980 and 2016, in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca (in English and French). Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ↑ Lee, Maureen Elgersman (2005). Black Bangor: African Americans in a Maine Community, 1880-1950. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-58465-499-5.

- ↑ Moynagh, Maureen. "Mapping Africadia's Imaginary Geography: An Interview with George Elliott Clarke" (PDF). Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ↑ "Black History Month – February 2023". NBM-MNB. 28 February 2023.

- ↑ "New Brunswick's Black History - The Argosy". 11 February 2015.

- ↑ "STAGE BRIEF SIT-IN". da.tj.news. Moncton Transcript. May 13, 1964. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ↑ Cox, Aidan. "From Ivory Coast to the Acadian Peninsula: How Shippagan's new mayor came to call N.B. home". CBC. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ Perry, Brad. "Black History Society Opens New Heritage Room". Country 94. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ↑ Hodges, Graham Russell (1996). The Black Loyalist Directory. New York: Garland Publishing Inc.

- ↑ Paz, Franco (3 December 2021). "W.A. Spray, The Blacks in New Brunswick". Journal of New Brunswick Studies. 13 (2): 159–160.

- ↑ "Carleton Lodge No. 41 Independent Order of Oddfellows Hall - Woodstock, NB - Atlantic Canada Heritage Properties on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ↑ Elgersman Lee, Maureen (2005). Black Bangor : African Americans in a Maine community, 1880-1950. Durham, N.H.: University of New Hampshire Press. p. 37. ISBN 1584654996.

- ↑ Burgos, Maria Jose. "Ubuntu in Fredericton: Somali newcomer keeps up an African tradition of helping others". CBC. Retrieved 20 March 2022.