Blackwall Yard is a small body of water that used to be a shipyard on the River Thames in Blackwall, engaged in ship building and later ship repairs for over 350 years. The yard closed in 1987.

History

East India Company

Blackwall was a shipbuilding area since the Middle Ages. In 1607, the Honorable East India Company (HEIC) decided to build its own ships and leased a yard in Deptford. Initially, this change of policy proved profitable as the first ships cost the Company about £10 per ton instead of the £45 per ton that it had been paying to have ships built for it. However, the situation changed as the Deptford yard came to be expensive to run.

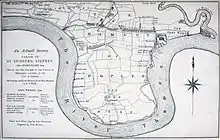

In 1614 the East India Company outgrew Deptford and ordered William Burrell to begin work on a new yard for repair, construction and loading of out-going ships. The site Burrell selected was at Blackwall, which was further down river and had deeper water, allowing laden ships to moor closer to the dock. The new yard was fully operational by 1617. The yard and its facilities were enlarged repeatedly during the early 17th Century. The yard was surrounded by a 12-foot (3.7 m) high wall, but was not used for storage of imported goods. [1] Later on in the 17th century the East India Company reverted to its original practice of hiring vessels. In many cases the owners who chartered their vessel to the East India Company had them built at Deptford and Blackwall.

Johnsons

In 1656, following a decline in the East India Company's fortunes, the yard was sold to shipwright Henry Johnson (later Sir Henry), who was already leasing the docks and part of the yard. The premises sold included three docks, two launching slips, two cranes and storehouses. Johnson went on to expand the yard, which continued to build and repair ships for the East India company as well as other activities.

The Anglo-Dutch wars of the late 17th Century resulted in too much work for the royal dockyards, and the Navy Board under Samuel Pepys began to commission third rates from Blackwall which was by then the largest private yard on the Thames. A new dock of 1½ acres constructed in the 1660s was the largest wet dock in England until the construction of the Howland Great Wet Dock in Rotherhithe. Construction of merchant ships continued, with Blackwall building 12 ships between 1670 and 1677 in a period when a bounty was offered to shipbuilders by Charles II. Following Johnson's death in 1683 the yard passed to Henry's son Henry Johnson (junior), who was not a shipwright, but left the management to others, including his brother William Johnson. After William's death in 1718 on a posting as Governor of Cape Coast Castle for the Royal African Company, the yard had little work until sold in 1724 and was overtaken in importance by Bronsdens yard at Deptford. With the end of the Dutch wars naval shipbuilding had also retreated to the royal yards. This was reversed by war with Spain in 1739.[1]

Perrys

The yard continued to repair and build ships, particularly for the East India Company, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. The yard recovered under the management and later ownership of the Perry family. When the Navy again surveyed the yard in 1742, the yard had the greatest capacity on the Thames. In 1784 when Francis Holman painted it, it was said to be the biggest private yard in the world.[2] It was at this time that the Perrys began construction of the large Brunswick Dock to the east of the yard, opened in 1790.

The yard was reduced in size in 1803 when the East India Dock company bought the eastern part including the Brunswick Dock. The Brunswick Dock became the East India Export Dock (the southern of two docks), which in the 20th Century was filled to become the site of Brunswick Wharf Power Station. In the 1830s the London and Blackwall Railway isolated the northern part of the remaining site, which the company then sold off.

Wigram and Green

As the Perrys began to withdraw from the business the firm became Perry Sons & Green (George Green having married John Perry's second daughter, Sarah in 1796), Perry Wells & Green (a half share having been sold to Rotherhithe shipbuilder John Wells) and eventually Wigram & Green. In 1821 the firm built its first steamship. During this period the yard built Blackwall Frigates.

In 1834 the paddle-steamer Nile was built for delivery to the Egyptian Navy. William Light captained the ship from London to Alexandria, reaching Alexandria in September. John Hindmarsh, who had prepared the steamer for delivery at Blackwall, travelled as a passenger on the ship on its journey to Egypt, and was made captain of the ship by November.[3][4][5]

Wigrams

In 1843 the remaining site was split into two yards, with Money Wigram & Sons in the western yard. Wigrams soon began construction of iron ships, but ceased building in 1876.[6] In 1877 Wigram's yard was bought by the Midland Railway and developed as a coal dock, which survived until the 1950s. This was known as Poplar Dock, not to be confused with the North London Railway's Poplar Dock built in 1851 further west,[7] and still in use as a marina. During World War II the dock was seriously damaged by bombing and it was later filled in and used as a fuel oil storage yard by Charringtons. Part of the site is now occupied by the northern ventilation shaft of the second Blackwall Tunnel and the rest by housing.

Greens

The eastern yard was occupied by R & H Green. Greens demolished earlier buildings in order to extend the dry dock, known as the eastern or lower graving dock. This was progressively lengthened and reduced in width. By 1882 it was 335 ft long (102 m) and 62 ft wide (19 m), with a wooden bottom and brick sides. In 1878 they opened the 'new' or upper graving dock. This was 410 ft long (120 m) [later lengthened to 471 ft (144 m)], 65 ft wide (20 m) at the entrance, and 23 ft deep (7.0 m). Greens continued building wooden ships longer than Wigrams, including 25 naval vessels, 14 of them 200-ton gunboats, during the Crimean War. Their first iron ship was built in 1866.

R. & H. Green Ltd continued to build ships at Blackwall until 1907. In 1910 the company amalgamated with Silley Weir & Company, as R.& H. Green and Silley Weir Ltd, with further premises at the Royal Albert dry docks. The company grew rapidly until the outbreak of the First World War, concentrating on repairing vessels. Throughout the war the firm constructed and repaired munitions ships, minesweepers, hospital ships and destroyers.

After the war a major programme of building and refurbishment was begun at the yard. A marine engineering shop was built between the two graving docks. This was nearly 350 ft long (110 m), over 100 ft wide (30 m) and nearly 60 ft high (18 m), and dominated the yard until the late 1980s. Their head office was located at the YMCA Building in Greengate Street, Plaistow E13, and they remained there, almost at the last occupants, until the company finally moved out in 1981.

In 1977 the company merged with the London Graving Dock Company Ltd (located on the SE of Blackwall Basin in the West India Docks) to form River Thames Shiprepairers Ltd, as a division of the nationalized British Shipbuilders. The Blackwall site became known as Blackwall Engineering and continued in operation until 1987.

Redevelopment

The upper graving dock remained in use until closure. In 1989 it was partially filled in and the new Reuters building was constructed, straddling it. The eastern dry dock (one of the earliest remaining on the Thames) was refurbished in 1991–92.[8][9][10]

In 2021, plans to redevelop the 1.7ha Blackwall Yard were published, including five buildings ranging from nine to 39-storeys tall, with the former graving dock to become an open-air swimming pool.[11]

Ships

- HMS Warspite, 62 guns was built 1665-6 by Johnsons, at a cost of £6,090.

- HMS Belliqueux, 1780 by Perrys, a 64-gun ship of 1,376 tons.

- HMS Powerful, 1783 by Perrys, a 74-gun ship.

- HMS Vennable, 1784 by Perrys, a 74-gun ship, of 1,652 tons.

- HMS Hannibal, also of 1,652 tons, was built by Perrys between June 1782 and April 1786 at a cost of £31,509.

- Warley. Perrys built two East Indiamen by the name of Warley, one in 1788 and one in 1796.

- HMS Albion, 1802 by Perrys. A third-rate of 1729 tons.

- 109 ton Paddlewheel steamer SS Beaver launched in 1835 for use in the Columbia District by the Hudson's Bay Company

- Alfred, 1845 by Greens. Indiaman.[12]

- PS Ripon, a paddlesteamer built in 1846 for P&O.

- HMS Terpsichore, launched by Wigrams in 1847.

- Indus, 1,782-ton paddle steamer by Wigrams in 1847.

- Yard Nos. 275, 278, 282 were lightships built in 1847.

- Yard No. 279 was the tea clipper Sea Witch built in 1848.

- Yard No. 291 was the famous tea clipper Challenger built in 1852. 174 ft (53 m) by 32 ft (9.8 m) by 20 ft (6.1 m) deep.

- Radetzky, launched by Wigrams in 1854 for the Austrian navy.

- Steam frigate BAP Apurímac, launched by Greens in 1854 for the Peruvian navy.

- HMY Emperor, commissioned by Queen Victoria as a gift for the Japanese Emperor by R&H Green in 1857. Renamed Banryu by the Japanese.[13]

- Clipper ship Superb, 364 tons, launched by Greens in 1866.[14]

- HMS Crocodile, 4,173 ton troopship launched by Wigrams in 1867.

- Tug Gamecock, Tug by R & H Green, 1880.[15]

- Tug Stormcock, Tug by R & H Green, 1881.[15]

- Tug Woodcock, Tug by R & H Green, 1884.[15]

- Tug Sirdar, Twin screw steam tug by R & H Green, 1899.[16]

References

- 1 2 "'Blackwall Yard: Development, to c.1819'". Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 553-565. English Heritage. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ National Maritime Museum Archived 19 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Elder, David F. "Light, William (1786–1839)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967

- ↑ "Hindmarsh, Sir John (1785–1860))". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, (MUP), 1966

- ↑ "Egyptian Navy ships 1827-1838". Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

Nile (paddle steamer), 1834, 2. Built at London. Guns 2x10" shell guns. (dimensions : 190-3 x 32-8,5/54-0 x 21-9, 412 hp.)

- ↑ Banbury, Philip (1971). Shipbuilders of the Thames and Medway. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. pp. 289–291. ISBN 0-7153-4996-1.

- ↑ "'Poplar Dock: Historical development'". Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 336-341. English Heritage. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ portcities.org Archived 9 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "'Blackwall Yard: Development, c.1819-1991'". Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 565-574. English Heritage. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ National Maritime Museum Green Blackwall Collection Archived 10 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Morby, Aaron (19 July 2021). "900-home London Blackwall Yard towers approved". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Illustrated London News 12 April 1845

- ↑ King, Ian. "HMS Emperor (1857) (1st)". Britain's Navy. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ↑ Clipper ship 'Superb' - National Maritime Museum

- 1 2 3 Thames Tugs, Gamecock Steam Towing Co. Ltd

- ↑ Thames Tugs, Port of London Authority

External links

Further reading

- Lubbock, Basil (1922). Blackwall Frigates. available online at

- Robert Wigram; Henry Green (1881). Chronicles of Blackwall yard. available online at