A bougnat ([bu.ɲa]) was a term for a person who moved from rural France to Paris, originally from the Massif Central and more specifically from Aubrac, Viadène, the Monts du Cantal, the Planèze of Saint-Flour and the Lot valley. After taking up the job of water-carrier (for the public baths) in the 19th century, they turned to trading in firewood and coal delivery, drinks (wine, spirits, lemonade), hostelry and sometimes had a sideline in scrap. This change of occupation went on during the Second French Empire, as Paris developed its water supply network.[1]

Etymology

At this time, Parisians started calling them bougnats. The word came to be associated with charbonniers (Charcoal burners) and the Auvergnat dialect.[Note 1] (Auvergnat dialect: charbouniat). The origin of this strong alliance between Auvergne and coal may be from the Brassac-les-Mines coal sold in Paris.[2]

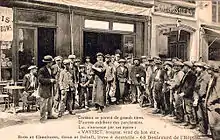

The term expanded meaning, to include the sense of Parisian cafés owned by bougnats, which would both sell drinks and deliver coal. They were in every working-class district, and one would often see the signage Vins et charbons ("wine and coal").

History

Hard-working, and with a close-knit community, many had success stories.

Today, although many Paris cafés have changed ownership, the community of Aveyronnais (Rouergat) owners is still well represented, and is relatively well-off, as illustrated in the film XXL (with Gérard Depardieu) in which the director draws an interesting parallel with the Jewish community that lives alongside, in the Sentier district, and which in some ways it resembles.

The husband would deliver the coal, while his wife would serve the customers. Some also served meals, and had rooms to let. The golden age of the bougnats was the first half of the 20th century.

There is still at least one bougnat in Paris, on the Rue Émile-Lepeu in the 11th arrondissement.[3]

Famous bougnats

Without doubt, the standard for the bougnat is Marcellin Cazes (born 1888 in Laguiole, Aveyron). He started as a commis waiter in a bougnat, before opening his own, first in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, and later at Les Halles. In 1920, he bought a well-regarded establishment, the Brasserie Lipp, and in 1931 the Balzar, on the Rue des Écoles. In 1935, he started a literary prize, the Prix Cazes, which is still awarded each year.

Another bougnat of note is Paul Boubal (1908 – 1988), born in Sainte-Eulalie-d'Olt, Aveyron. He was owner-manager of the Café de Flore, which he bought in 1939 and ran until 1983. His parents had settled in the Rue Ordener, in the 18th arrondissement.[4]

More recently, another Aveyronnais from around Languole, Gilbert Costes, from a modest country family, went on to own, with them, around forty Parisian establishments. In 1999, he became President of the Tribunal de commerce de Paris.[5]

In art and literature

The bougnat appears in the songs of Georges Brassens (Brave Margot) and Jacques Brel (Mathilde: "Bougnat, apporte-nous du vin, celui des noces et des festins" – "Bougnat, bring us wine, that for weddings and feasts").

In literature, bougnats appear in the works of Blaise Cendrars and more so in Marcel Aymé, where is mae the hero of his novella Le Mariage de César[Note 2] (The Marriage of César). Lesser-known authors such as Joseph Bialot (Bialot 1990) and Marc Tardieu (Tardieu 2000, Tardieu 2001) have also made the bougnat a central character in their work.

In Asterix and the Chieftain's Shield, the eleventh collection of The Adventures of Asterix, the town of Gergovie is full of "wine and coal" shops, in reference to the bougnats.

See also

- L'Auvergnat de Paris, a weekly trade magazine for café and brasserie owners

Notes

- ↑ According to Wirth 1996 himself citing from Anon 1987, p. 27, the word derived from the shouts of those delivering coal: de carbou n'ia.

- ↑ The novel starts: "Il y avait à Montmartre un bougnat vertueux qui s'appelait César. Il tenait boutique de vins et charbons à l'enseigne des 'Enfants du Massif'." ("There was in Montmartre a kindly bougnat, called César. He ran a shop selling wine and coal, under the sign of the 'Children of the Massif'."

Sources

- Wirth, Laurent (1996). Un équilibre perdu : évolution démographique, économique et sociale du monde paysan dans le Cantal au XIXème [A lost balance: demographic, economic and social evolution of country life in 19th-century Cantal] (in French). Clermont-Ferrand, Institut d'études du Massif central. p. 209. ISBN 2-87741-073-0.

- Anon (1987). Les Auvergnats de Paris, hier et aujourd'hui [Paris Auvergnats, Yesterday and Today] (in French). Ligue auvergnate et du Massif central.

- Bialot, Joseph (1990). Le Royal-bougnat. Série noire (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-049239-7.

- Tardieu, Marc (2000). Le Bougnat (in French). Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 2-268-03484-4.

- Tardieu, Marc (2001). Les Auvergnats de Paris (in French). Paris: Le Grand Livre du mois. ISBN 2-7028-4757-9.

References

- ↑ Wirth 1996, p. 209.

- ↑ Monange, Jean (1 May 2001). "Les Auvergnats de Paris". www.histoire-genealogie.com (in French). Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "Le dernier bougnat de Paris" [The last bougnat in Paris]. www.aveyron.com (in French). Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ See also the work of his grandson Christophe Durand (pen-name Boubal): Boubal, Christophe (2004). Café de Flore : L'esprit d'un siècle. Littératures (in French). Fernand Lanore. ISBN 2-85157-251-2.

- ↑ "Gilbert Costes, le comptoir à la barre". Le Nouvel Économiste (in French). No. 1231. 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-03-12.