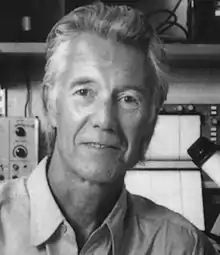

Brian Carey Goodwin (25 March 1931 – 15 July 2009) (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada - Dartington, Totnes, Devon, UK) was a Canadian mathematician and biologist, a Professor Emeritus at the Open University and a founder of theoretical biology and biomathematics. He introduced the use of complex systems and generative models in developmental biology. He suggested that a reductionist view of nature fails to explain complex features, controversially proposing the structuralist theory that morphogenetic fields might substitute for natural selection in driving evolution.[1] He was also a visible member of the Third Culture movement.[2]

Biography

Brian Goodwin was born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada in 1931. He studied biology at McGill University and then emigrated to the UK, under a Rhodes Scholarship for studying mathematics at Oxford. He got his PhD at the University of Edinburgh presenting the thesis "Studies in the general theory of development and evolution"[3] under the supervision of Conrad Hal Waddington. He then moved to Sussex University until 1983 when he became a full professor at the Open University in Milton Keynes until retirement in 1992. He became a major figure in the early development of mathematical biology, along with other researchers. He was one of the attendants to the famous meetings that took place between 1965 and 1968 in Villa Serbelloni, hosted by the Rockefeller Foundation, under the topic "Towards a theoretical Biology".

Thereafter, he taught at the Schumacher College in Devon, UK, where he was instrumental in starting the college's MSc in Holistic Science. He was made a Founding Fellow of Schumacher College shortly before his death. Goodwin also had a research position at MIT and was a long time visitor of several institutions including the UNAM in Mexico City. He was a founding member of the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico where he also served as a member of the science board for several years.[4][5]

Brian Goodwin died in hospital in 2009, after surgery resulting from a fall from his bicycle.[6] Goodwin is survived by his third wife, Christel, and his daughter, Lynn.

Gene networks and development

Shortly after François Jacob and Jacques Monod developed their first model of gene regulation, Goodwin proposed the first model of a genetic oscillator, showing that regulatory interactions among genes allowed periodic fluctuations to occur. Shortly after this model became published, he also formulated a general theory of complex gene regulatory networks using statistical mechanics. In its simplest form, Goodwin's oscillator involves a single gene that represses itself. Goodwin equations were originally formulated in terms of conservative (Hamiltonian) systems, thus not taking into account dissipative effects that are required in a realistic approach to regulatory phenomena in biology. Many versions have been developed since then. The simplest (but realistic) formulation considers three variables, X, Y and Z indicating the concentrations of RNA, protein and end product which generates the negative feedback loop. The equations are

and closed oscillations can occur for n>8 and behave limit cycles: after a perturbation of the system's state, it returns to its previous attractor. A simple modification of this model, adding other terms introducing additional steps in the transcription machinery allows to find oscillations for smaller n values. Goodwin's model and its extensions have been widely used over the years as the basic skeleton for other models of oscillatory behavior, including circadian clocks, cell division or physiological control systems.

Developmental biology

In the field of developmental biology, Goodwin explored self-organization in pattern formation, using case studies from single-cell (as Acetabularia) to multicellular organisms, including early development in Drosophila. He proposed that morphogenetic fields, defined in terms of spatial distributions of chemical signals (morphogenes), could pattern and shape the embryo. In this way, geometry and development were linked through a mathematical formalism. Along with his colleague Lynn Trainor, Goodwin developed a set of mathematical equations describing the changes of both physical boundaries in the organism and chemical gradients.

By considering the mechanochemical behaviour of the cortical cytoplasm (or cytogel) of plant cells, a viscoelastic material mainly composed of actin microfilaments and reinforced by a microtubules network, Goodwin & Trainor (1985) showed how to couple calcium and the mechanical properties of the cytoplasm. The cytogel is treated as a continuous viscoelastic medium in which calcium ions can diffuse and interact with the cytoskeleton. The model consists in two non-linear partial differential equations which describe the evolution of the mechanical strain field and of the calcium distribution in the cytogel.

It has been shown (Trainor & Goodwin, 1986) that, in a range of parameter values, instabilities may occur and develop in this system, leading to intracellular patterns of strain and calcium concentration. The equations read, in their general form:

These equations describe the spatiotemporal dynamics of the displacement from the reference state and the calcium concentration, respectively. Here x and t are the space and time coordinates, respectively. These equations can be applied to many different scenarios and the different functions P(x) introduce the specific mechanical properties of the medium. These equations can generate a rich variety of static and dynamic patterns, from complex geometrical motifs to oscillations and chaos (Briere 1994).

Structuralism

He was also a strong advocate of the view that genes cannot fully explain the complexity of biological systems. In that sense, he became one of the strongest defenders of the systems view against reductionism. He suggested that nonlinear phenomena and the fundamental laws defining their behavior were essential to understand biology and its evolutionary paths. His position within evolutionary biology can be defined as a structuralist one. To Goodwin, many patterns in nature are a byproduct of constraints imposed by complexity. The limited repertoire of motifs observed in the spatial organization of plants and animals (at some scales) would be, in Goodwin's opinion, a fingerprint of the role played by such constraints. The role of natural selection would be secondary.

These opinions were highly controversial, and they brought Goodwin into conflict with many prominent Darwinian evolutionists, whereas some physicists found some of his views natural. Physicist Murray Gell-Mann for example acknowledged that "when biological evolution — based on largely random variation in genetic material and on natural selection — operates on the structure of actual organisms, it does so subject to the laws of physical science, which place crucial limitations on how living things can be constructed." Richard Dawkins, the former professor for public understanding of science at Oxford University and a well known Darwinian evolutionist, conceded: "I don't think there's much good evidence to support [his thesis], but it's important that somebody like Brian Goodwin is saying that kind of thing, because it provides the other extreme, and the truth probably lies somewhere between." Dawkins also agreed that "It's a genuinely interesting possibility that the underlying laws of morphology allow only a certain limited range of shapes.". For his part, Goodwin did not reject basic Darwinism, only its excesses.

Reception

Biologist Gert Korthof has praised the research of Goodwin commenting he tried to "improve Darwinism in a scientific way."[7] David B. Wake has also positively reviewed Goodwin's research describing him as a "thoughtful scientist, one of the great dissenters from the orthodoxies of modern evolutionary, genetic and developmental biology".[8]

Goodwin had argued that natural selection was "too weak [a] force" to explain evolution and only operated as a filter mechanism. He claimed that modern evolutionary biology failed to provide an explanation for the theory of biological form and had ignored the importance of morphogenesis in evolution. He claimed to provide a new evolutionary theory to replace neo-Darwinism. In a critical review, biologist Catherine S. C. Price noted that although he had succeeded in providing an alternative to mutation as the only source of variation, he failed to provide an alternative to natural selection as a mechanism of adaptation.[9] Price claimed Goodwin's "discussion of evolution is biased, insufficiently developed and poorly informed", and that he misrepresented Darwinism, used straw man arguments and ignored research from population genetics.[9]

The evolutionary biologist Günter P. Wagner described Goodwin's structuralism as "a fringe movement in evolutionary biology".[10]

Publications

- Books

- 1963. Temporal Organization in Cells Academic Press, London 1963, ISBN 1376206161

- 1989. Theoretical Biology: Epigenetic and Evolutionary Order for Complex Systems with Peter Saunders, Edinburgh University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-85224-600-5

- 1994. Mechanical Engineering of the Cytoskeleton in Developmental Biology (International Review of Cytology), with Kwang W. Jeon and Richard J. Gordon, Academic Press, London 1994, ISBN 0-12-364553-0

- 1996. Form and Transformation: Generative and Relational Principles in Biology, Cambridge Univ Press, 1996.

- 1997. How the Leopard Changed its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity, Scribner, 1994, ISBN 0-02-544710-6 (German: Der Leopard, der seine Flecken verliert, Piper, München 1997, ISBN 3-492-03873-5)

- 2001. Signs of Life: How Complexity Pervades Biology, with Ricard V. Solé, Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 0-465-01927-7

- 2007. Nature's Due: Healing Our Fragmented Culture, Floris Books, 2007, ISBN 0-86315-596-0

- Selected Scientific papers

- Goodwin, BC 1965, "Oscillatory behaviour in enzymatic control processes", Adv. Enz. Reg. 3: 425-428.

- Goodwin BC 1978, "A cognitive view of biological process." J Soc Biol Structures 1:117-125

- Gordon, DM, Goodwin, BC and Trainor LEH 1992, "A parallel distributed model of the behaviour of ant colonies", J. Theor. Biol. 156, 293-307.

- 1997, "Temporal organization and disorganization in organisms". in: Chronobiology International 14 (5): 531-536 1997

- Goodwin BC, 1978 "A cognitive view of biological process", J. Soc. Biol. Struct. 1, 117-125.

- 2000, "The life of form. Emergent patterns of morphological transformation". in: Comptes rendud de la Academie des Science III 323 (1): 15-21 JAN 2000

- Goodwin BC (2000). The life of form. Emergent patterns of morphological transformation. Comptes rendus de l'academie des sciencies III - Sciences de la vie-life sciences 323 (1): 15-21

- Goodwin BC. (1997) Temporal organization and disorganization in organisms. Chronobiology international 14 (5): 531-536

- Solé, R., O. Miramontes y Goodwin BC. (1993) "Order and chaos in ant societies". J. Theor. Biol. 161: 343

- Miramontes, O., R. Solé y BC Goodwin (1993), Collective Behaviour of Random-Activated Mobile Cellular Automata. Physica D 63: 145-160

- Jaeger, J. and Goodwin BC 2001, "A cellular oscillator model for periodic pattern formation" J. Theor. Biol. 213, 71-181.

- 2002, "In the Shadow of Culture". in: "The Next Fifty Years: Science in the First Half of the Twenty-First Century" Edited by John Brockman, Vintage Books, MAY 2002, ISBN 0-375-71342-5

- Goodwin B 2005, "Meaning in evolution" J. Biol. Phys. Chem. 5, 51–56.

References

- ↑ Dickinson, W. Joseph. (1998). Form and Transformation: Generative and Relational Principles in Biology. by Gerry Webster; Brian Goodwin. The Quarterly Review of Biology. Vol. 73, No. 1. pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Brian Goodwin obituary - The Guardian, 9 August 2009

- ↑ Goodwin, Brian C. (1961). Studies in the general theory of development and evolution (Thesis). University of Edinburgh.

- ↑ Brian Goodwin Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, SteinerBooks

- ↑ Brian Goodwin Obituary - The Independent, 31 July 2009.

- ↑ Professor Brian Goodwin Archived 13 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Schumacher College

- ↑ "How the Leopard Changed Its Spots". Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ↑ Wake, David B. (1996). How the Leopard Changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity by Brian Goodwin. American Scientist. Vol. 84, No. 3. pp. 300-301.

- 1 2 Price, Catherine S. C. (1995). Structurally Unsound. Evolution. Vol. 49, No. 6. pp. 1298-1302.

- ↑ Wagner, Günter P., Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation. Princeton University Press. 2014. Chapter 1: The Intellectual Challenge of Morphological Evolution: A Case for Variational Structuralism. Page 7