A broadside is a large sheet of paper printed on one side only.[1] Historically in Europe, broadsides were used as posters, announcing events or proclamations, giving political views, commentary in the form of ballads, or simply advertisements. In Japan, chromoxylographic broadsheets featuring artistic prints were common.

Description and history

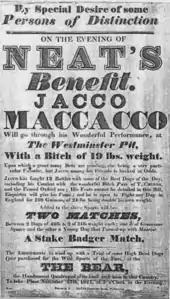

The historical type of broadsides, designed to be plastered onto walls as a form of street literature, were ephemera, i.e., temporary documents created for a specific purpose and intended to be thrown away. They were one of the most common forms of printed material between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. They were often advertisements, but could also be used for news information or proclamations.

Broadsides were a very popular medium for printing topical ballads starting in the 16th century. Broadside ballads were usually printed on the cheapest type of paper available. Initially, this was cloth paper, but later it became common to use sheets of thinner, cheaper paper (pulp). In Victorian era London they were sold for a penny or half-penny. The sheets on which broadsides were printed could also be folded, twice or more, to make small pamphlets or chapbooks. Collections of songs in chapbooks were known as garlands. Broadside ballads lasted longer in Ireland, and although never produced in such huge numbers in North America, they were significant in the eighteenth century and provided an important medium of propaganda, on both sides, in the American War of Independence.[2]

Broadsides were commonly sold at public executions in the United Kingdom in the 18th and 19th centuries. These were often produced by printers who specialised in them. They could be illustrated by a crude picture of the crime, a portrait of the criminal, or a generic woodcut of a hanging taking place. There would be a written account of the crime and of the trial and often the criminal's confession of guilt. A doggerel verse warning others to not follow the executed person's example, to avoid their fate, was another common feature.[3]

By the mid-19th century, the advent of newspapers and inexpensive novels resulted in the demise of the street literature broadside.

One classic example of a broadside used for proclamations is the Dunlap broadside, which was the first publication of the United States Declaration of Independence, printed on the night of July 4, 1776 by John Dunlap of Philadelphia in an estimated 200 copies.[4] An example of a broadside used for news information is the first published account of George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River, printed on December 30, 1776, by an unknown printer.[5] In nineteenth-century Pennsylvania, broadsides were used by the Pennsylvania Dutch to advertise the "vendu", or county sale, for religious instruction, and to publish Trauerlieder or "sorrow songs" for sale.[6]

Today, broadside printing is done by many smaller printers and publishers as a fine art variant, with poems often being available as broadsides, intended to be framed and hung on the wall. Broadsides pasted on walls are still used as a form of mass communication in Haredi Jewish communities, where they are known by the Yiddish term "pashkevil" (pasquil).[7] Originally, a pasquil was used to ridicule public authority figures, to publicly criticize the powers, and to impart to the public information that is being withheld.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ ILAB: Definition of term: Broadside Retrieved 2011-07-06

- ↑ M. Savelle, Seeds of liberty: The Genesis of the American Mind (Kessinger Publishing, 2005), p. 533.

- ↑ "Dying Speeches and Bloody Murders: Crime Broadsides Collected by Harvard Law School Library". Harvard University Law School Library. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ↑ Illustration for Widmer, Ted, "Looking for Liberty", op-ed commentary, The New York Times, July 4, 2008, accessed July 7, 2008

- ↑ Congress received the following intelligence from the Council of Safety, as coming from "an officer of distinction in the army" Retrieved 2023-02-06

- ↑ Yoder, Don; Woloson, Wendy (September 2005). "The Broadside in Public Life and The Broadside in Private Life". Pennsylvania German Broadsides: Windows into an American Culture. Library Company of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ Rena Rossner (December 9, 2005). "The writing on the wall". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Pashkevil. The Jerusalem Notice Board. Exhibition at The Isaac Kaplan Old Yishuv Court Museum". Museums in Israel. National Portal. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

Further reading

- A Book of Broadsheets; with an introduction by Geoffrey Dawson. London: Methuen, 1928 ("a reproduction ... of the pocket literature provided by The Times for the men in the trenches during the early days of the War ... every item in it was printed in the autumn of the year 1915 in the form of a broadsheet ..."—p. xi)

External links

- English Broadside Ballad Archive at the University of California, Santa Barbara

- Modern American Poetry Collection at Ball State University Archives and Special Collections Research Center

- Broadsided Contemporary, original broadsides published monthly online and posted around the US and abroad

- Poetry Center of Chicago Broadsides – fine letter press broadsides

- Green Linden Press Poetry Broadsides

- Historical broadsides

- Library of Congress – Three Centuries of Broadsides and other Printed Ephemera

- University of Georgia – Historical broadsides from 1849–1989

- Wake Forest University – Confederate Broadside Poetry Collection

- The Word on the Street. 1,800 Scottish broadsides from 1650–1910 at National Library of Scotland. NLS Broadsides dataset.

- Broadsides at the Boston Athenaeum

- Pennsylvania German Broadsides: Windows into an American Culture, Library Company of Philadelphia

- Crime broadsides

- Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library; a digitized collection of 500 crime and execution broadsides, from 1707 to 1891.