| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

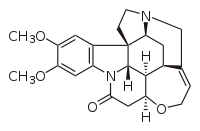

| IUPAC name

2,3-Dimethoxystrychnidin-10-one | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(4bR,4b1S,7aS,8aR,8a1R,12aS)-2,3-Dimethoxy-4b1,5,6,7a,8,8a,8a1,11,12a,13-decahydro-14H-12-oxa-7,14a-diaza-7,9-methanocyclohepta[cd]cyclopenta[g]fluoranthen-14-one | |

| Other names

2,3-Dimethoxystrychnine 10,11-Dimethoxystrychnine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.014 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1570 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C23H26N2O4 | |

| Molar mass | 394.471 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 178 °C (352 °F; 451 K) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H300, H330, H412 | |

| P260, P264, P270, P271, P273, P284, P301+P310, P304+P340, P310, P320, P321, P330, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Brucine, is an alkaloid closely related to strychnine, most commonly found in the Strychnos nux-vomica tree. Brucine poisoning is rare, since it is usually ingested with strychnine, and strychnine is more toxic than brucine. In synthetic chemistry, it can be used as a tool for stereospecific chemical syntheses.

Brucine is named from the genus Brucea, named after James Bruce who brought back Brucea antidysenterica from Ethiopia.

History

Brucine was discovered in 1819 by Pelletier and Caventou in the bark of the Strychnos nux-vomica tree.[1] While its structure was not deduced until much later, it was determined that it was closely related to strychnine in 1884, when the chemist Hanssen converted both strychnine and brucine into the same molecule.[2]

Identification

Brucine can be detected and quantified using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.[3] Historically, brucine was distinguished from strychnine by its reactivity toward chromic acid.[4]

Applications

Chemical applications

Since brucine is a large chiral molecule, it has been used in chiral resolution. Fisher first reported its use as a resolving agent in 1899, and it was the first natural product used as an organocatalyst in a reaction resulting in an enantiomeric enrichment by Marckwald, in 1904.[5] Its bromide salt has been used as the stationary phase in HPLC in order to selectively bind one of two anionic enantiomers.[6] Brucine has also been used in fractional distillation in acetone in order to resolve dihydroxy fatty acids,[7] as well as diarylcarbinols.[8]

Medical applications

While brucine has been shown to have good anti-tumor effects, on both hepatocellular carcinoma[9] and breast cancer,[10] its narrow therapeutic window has limited its use as a treatment for cancer.

Brucine is also used in traditional Chinese medicine as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic agent,[11] as well as in some Ayurveda and homeopathy drugs.[12]

Alcohol denaturant

Brucine is one of the many chemicals used as a denaturant to make alcohol unfit for human consumption.[13]

Cultural references

One of the most famous cultural references to brucine occurs in The Count of Monte Cristo, the novel by French author Alexandre Dumas. In a discussion of mithridatism, Monte Cristo states:

“Well, suppose, then, that this poison was brucine, and you were to take a milligramme the first day, two milligrams the second day, and so on…at the end of a month, when drinking water from the same carafe, you would kill the person who drank with you, without your perceiving…that there was any poisonous substance mingled with this water.”[14]

Brucine in also mentioned in the 1972 version of The Mechanic, in which the hitman Steve McKenna betrays his mentor, aging hitman Arthur Bishop, using a celebratory glass of wine spiked with brucine, leaving Bishop to die of an apparent heart attack.[15]

Such fictions run contrary to reality in the very properties which make brucine useful as a denaturant, and useless as a covert poison. While being only about one-eighth as toxic as strychnine, its threshold of bitterness occurs at 69% greater dilution. A drink laden with brucine, overwhelmingly bitter at far below lethal concentration, would cause an intended victim to gag on the first sip.

Safety

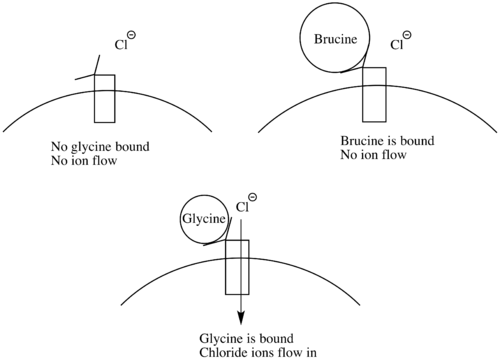

Brucine intoxication occurs very rarely, since it is usually ingested with strychnine. Symptoms of brucine intoxication include muscle spasms, convulsions, rhabdomyolysis, and acute kidney injury. Brucine’s mechanism of action closely resembles that of strychnine. It acts as an antagonist at glycine receptors and paralyzes inhibitory neurons.

The probable fatal dose of brucine in adults is 1 g.[16] In other animals, the LD50 varies considerably.

| Animal | Route of Entry | LD50[17] |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Subcutaneous | 60 mg/kg |

| Rat | Intraperitoneal | 91 mg/kg |

| Rabbit | Oral | 4 mg/kg |

References

- ↑ Wormley, T (1869). Micro-chemistry of poisons including their physiological, pathological, and legal relations : Adapted to the use of the medical jurist, physician, and general chemist. New York: W. Wood.

- ↑ Buckingham, J (2007). Bitter Nemesis: The Intimate History of Strychnine. CRC Press. p. 225.

- ↑ Teske, J; Weller, J; Albrecht, U; Fieguth, A (2011). "Fatal Intoxication Due to Brucine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 35 (4): 248–253. doi:10.1093/anatox/35.4.248. PMID 21513620.

- ↑ Glasby, J. (1975). Encyclopedia of the alkaloids. New York: Plenum Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780306308451.

- ↑ Koskinen, A (1993). Asymmetric synthesis of natural products. Chichester: J. Wiley. pp. 17, 28–29.

- ↑ Zarbua, K; Kral, V (2002). "Quaternized brucine as a novel chiral selector". Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 13 (23): 2567–2570. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(02)00715-2.

- ↑ Malkar, N; Kumar, V (1998). "Optical resolution of (±)-Threo-9,10,16-trihydroxy hexadecanoic acid using (−)brucine". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 75 (10): 1461–1463. doi:10.1007/s11746-998-0202-9. S2CID 83662051.

- ↑ Toda, F; Tanaka, K; Koshiro, K (1991). "A New Preparative Method for Optically Active Diarylcarbinols". Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2 (9): 873–874. doi:10.1016/s0957-4166(00)82198-9.

- ↑ Qin, J (2012). "Anti-Tumor Effects of Brucine Immune-Nanoparticles on Hepatocellular Carcinoma". International Journal of Nanomedicine. 7: 369–379. doi:10.2147/IJN.S27226. PMC 3273973. PMID 22334771.

- ↑ Serasanambati, M; Chilakapati, S; Vanagavaragu, J; Cilakapati, D (2014). "Inhibitory effect of gemcitabine and brucine on MDA MB-231 human breast cancer cells". International Journal of Drug Delivery. 6.

- ↑ Zhang, J; Wang, S; Chen, X; Zhide, H; Xiao, M (2003). "Capillary Electrophorese with Field-Enhanced Stacking for Rapid and Sensitive Determination of Strychnine and Brucine". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 376 (2): 210–213. doi:10.1007/s00216-003-1852-y. PMID 12692702. S2CID 7832819.

- ↑ Rathi, A; Srivastava, N; Khatoon, S; Rawat, A (2008). "TLC Determination of Strychnine and Brucine of Strychnos nun vomica in Ayurveda and Homeopathy Drugs". Chromatographia. 67 (7–8): 607–613. doi:10.1365/s10337-008-0556-z. S2CID 94626190.

- ↑ "List of denaturants authorized for denatured spirits". www.law.cornell.edu. Cornell Law School. 30 August 2016. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ↑ Dumas, Alexandre (1845). The Count of Monte Cristo. Feedbooks. p. 622.

- ↑ "Synopsis for The Mechanic". IMDb. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Gosselin, R. E.; Smith, R. P.; Hodge, H. C. (1984). Clinical Toxicology of Commercial Products (5 ed.). Baltimore/London: Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ "Brucine". TOXNET. NIH. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

External links

- Brucine, INCHEM.org