| 1897 Brussels | |

|---|---|

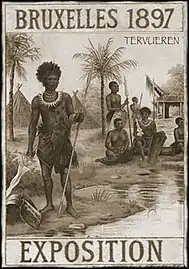

Exhibition poster by Art Nouveau artist Henri Privat-Livemont | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | Exposition Internationale de Bruxelles |

| Building(s) | Palace of the Colonies |

| Area | 36 hectares (89 acres) |

| Visitors | 6,000,000 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 27 |

| Location | |

| Country | Belgium |

| City | Brussels |

| Venue | |

| Coordinates | 50°50′30″N 4°23′19.4″E / 50.84167°N 4.388722°E |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | May 10, 1897 |

| Closure | November 8, 1897 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago |

| Next | Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris |

The Brussels International Exposition (French: Exposition Internationale de Bruxelles, Dutch: Wereldtentoonstelling te Brussel) of 1897 was a world's fair held in Brussels, Belgium, from 10 May 1897 through 8 November 1897. There were 27 participating countries, and an estimated attendance of 7.8 million people.

The main venues of the fair were the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark, as well as a colonial section in the suburb of Tervuren, showcasing King Leopold II's personal property: the Congo Free State.[1][2] The two exposition sites were linked by a purpose-built tramway.

Location

The exhibition took place on two different sites comprising 14 sections. The first was located in the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark in the easternmost part of the City of Brussels and constituted the main grounds of the fair, and the second in the Flemish suburb of Tervuren, consisted of a colonial section devoted to the Congo Free State, the personal property of King Leopold II.[1][2] The two sites were linked by a new tramway line and by the Avenue de Tervueren/Tervurenlaan, an 11 km-long (6.8 mi) grand alley also laid out for this purpose.

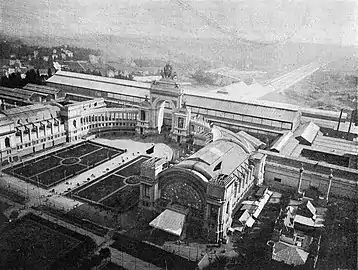

Postcard of the Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark section of the 1897 Brussels International Exposition

Postcard of the Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark section of the 1897 Brussels International Exposition View of the Cinquantenaire during the 1897 International Exposition

View of the Cinquantenaire during the 1897 International Exposition

Colonial exhibit

The Tervuren section was hosted in the Palace of the Colonies.[1][2] The building was designed by the French architect Alfred-Philibert Aldrophe and the classical gardens by the French landscape architect Elie Lainé. In the main hall, known as the Hall of the Great Cultures (French: Salon des Grandes Cultures), the architect and decorator Georges Hobé designed a distinctive wooden Art Nouveau structure to evoke a Congolese forest, using Bilinga wood, an African tree. The exhibition displayed ethnographic objects, stuffed animals and Congolese export products (e.g. coffee, cacao and tobacco). In the park, a temporary "human zoo"—a copy of an African village—was built, in which 60 Congolese people lived for the duration of the exhibition.[3] Seven of them, however, did not survive their forced stay in Belgium.[4] This exhibition's success led to the permanent establishment of the Museum of the Congo (today's Royal Museum for Central Africa) in 1898.

Art Nouveau

The primary designers of the fair were among the Belgian masters of Art Nouveau architecture at the height of the style: Henry van de Velde, Paul Hankar, Gédéon Bordiau, and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy. Henri Privat-Livemont produced posters for the exposition.

There seems to be few physical remnants. The small neoclassical pavilion called the Temple of Human Passions that Victor Horta designed to house a sculptural relief by Jef Lambeaux was completed in time for the fair, but its opening was delayed by disputes until 1899.

Vieux-Bruxelles

A public favorite at the World's Fair was Vieux-Bruxelles (also called Bruxelles-Kermesse), a miniature city and theme park evoking Brussels around 1830. Conceived by George Garnir, and designed by Jules Barbier (not to be confused with the Parisian author), Gombeaux and Ghyssels, with dioramas painted by Albert Dubosq, Pierre Devis and Armand Lynen, the section occupied 25,000 m2 (270,000 sq ft) of the Parc du Cinquantenaire. Its construction begun on 19 October 1896 and its inauguration took place on 24 April 1897. Somewhat foreshadowing Main Street at Disneyland, Vieux-Bruxelles offered visitors nostalgic, smaller-size reproductions of historic buildings. As Charles Vogel put it,

Bruxelles-Kermesse is the popular city with its numerous distractions, its casual pleasures, its elements of gaiety everywhere renewed. … The visitor is first struck by a set of various constructions: houses , monumental gates, towers, among which stands majestically that of the Chien-Vert restaurant. This is our old town with – reduced to a slightly reduced scale – its buildings of yesteryear, some of which still exist have been faithfully copied and give, thanks to the staff, the absolute illusion of reality. … The entrance to Brussels-Kermesse is the Porte du Rivage, then come the house of the Count of Egmont, the house of the Trois-Têtes, the Auberge Saint-Laurent, adjoining at the Hôtel Ravenstein, – the house of the Cheval Marin, the old Butter Market, the Hotel de Nassau, – which, with its superb pear-shaped spire tower, gives asylum to the restaurant estaminet of the Green Dog already named, – the old gate of Ghent or Flanders, of an astounding illusionism; the fountain of Manneken-Piss [sic] and that of the Three Pucelles … Should we talk about the Moulin Saint-Michel, the house of Barques, the door of the old Sainte-Catherine church?[5]

Participating countries

Some 27 countries took part in the exhibition, most of them from Europe. For these countries, the pavilions were, as it were, a showcase of their power, wealth and technical skills. With the exception of Oceania, all continents were represented in the exposition. The participating countries were:

| Participating Nations |

|---|

Commemoration

.jpg.webp) Commemorative stamp and postmark

Commemorative stamp and postmark.jpg.webp) Postcard

Postcard

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Schroeder-Gudehus & Rasmussen 1992, p. 128–131.

- 1 2 3 Aubry 2000, p. 179.

- ↑ Dirk F.E. Thys van den Audenaerde, Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale (in French), Brussels, Crédit communal, coll. "Musea Nostra" (no 32), 1994, p. 8–9

- ↑ Hochschild 1998.

- ↑ L'Éventail, 25 April 1897.

- ↑ Imprimerie Ricouart-Dugour, ed. (1897). "Exposition Internationale de Bruxelles 1897". Anzin. p. 12.

Bibliography

- Aubry, Françoise (2000). "L'exposition de Tervueren en 1897 : scénographie Art nouveau et arts primitifs". Bruxelles carrefour de cultures (in French). Brussels: Mercator. ISBN 978-90-6153-457-0.

- Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost. Boston: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-358-21250-8.

- Schroeder-Gudehus, Brigitte; Rasmussen, Anne (1992). Les fastes du progrès : le guide des expositions universelles 1851-1992 (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-012617-7.

External links

- Official website of the BIE

- Brussels International Exposition pdf

- BIE description (in French; pdf format)

- photos of the Congo display

![Wooden structure by Georges Hobé [fr] in the Hall of the Great Cultures during the exhibition](../I/Tervuren_1897_salon_des_grandes_cultures.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)