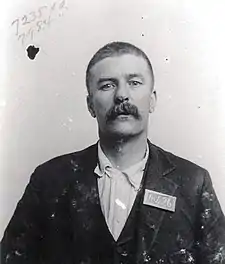

Buck English (1855 – January 15, 1915) was an American Old West outlaw, and one of Lake County, California's most notorious thieves and stagecoach robbers toward the end of the 19th century.[1]

Early life

Born Lawrence Buchanen English in Oregon, he soon received the nickname "Buck".[2] The English family feuded with the Durbin family for years, which led to three of Buck's brothers dying. When Buck was thirteen, he became obligated to take revenge on the Durbin family. Unlike Black Bart, Lake County's other notorious thief, Buck was rash and openly flaunted his overconfident capacity.

He was only 22 years old when he and a companion held up the Lower Lake stage coach and took the Wells Fargo strongbox from the driver. Instead of the usual gold or silver for the miners, the box yielded only two brass castings. The local newspaper later said, "Shortly before this robbery, he and his companion met four Chinese miners coming down from the Great Western Mine (near Middletown), and robbed them of their watches and money."

Territory

Wells Fargo strongboxes were often the target of stagecoach robbers in Middletown. After the mid-19th century, the payroll money was brought in on the stagecoach with an armed guard beside the driver. Not all of the holdups in the area were the doing of Buck and his gang, although he was a scourge to the local vicinity for a number of years. Buck worked the road near Mountain Hill House, south of Middletown, or near the double bridge north of Middletown near Lower Lake. For 20 years, Buck roamed the countryside, making little effort to hide his identity or his disreputable enterprise.

Duel

Buck walked the streets of Middletown with a six-shooter strapped to his side, daring any who insulted his authority to a contest. One day, he ran into Captain Good on the main street, and harsh words were exchanged. Later in the day, they met again, and this time it was a shooting affair, with Buck emerging unscathed. The captain was seriously wounded in the arm and legs. In another unrelated incident, Buck shot and killed a man in the Middletown skating rink, turning the arena into a scene of pandemonium.

After jail time

After his release from San Quentin in 1882, Buck returned to Middletown. Soon after his arrival, the Lebree store in town was robbed of some watches and jewelry.

Buck left Middletown for a few years, but upon his return, he showed he had not changed. It was not long before he held up the stage at the foot of Mount Saint Helena, near the summer home of the mayor of San Francisco. The six passengers were ordered out of the stage, and stripped of their possessions. Buck made no effort to hide his identity. He greeted the driver of a passing wagon, who quickly drove on when he realized a robbery was in progress.

Capture

This occurred on May 7, 1895. A posse was formed and they set off to capture Buck. They discovered him on a stagecoach going from Monticello to Napa, and a wild chase ensued. The San Francisco Examiner reported the next day:

One of the robbers jumped to the horses ahead and leveled his guns. He waved weapons and spouted profanity, all the while threatening to "blow" the driver off of the seat. The two robbers were armed with old style Colt revolvers, and he cursed at everyone, especially the Chinamen

The capture of Buck by Sheriff Bell reads like a Wild West novel. He was so badly wounded and had lost so much blood that many thought he would not survive. He did recover, however, and returned to San Quentin to serve yet another sentence.[2]

Buck was not as well known as Black Bart and other Western gunmen of the time, but he created fear wherever he went. Although he was arrested for his robberies and attacks on the general population, Buck had his hands in many other criminal activities, including cattle rustling, which he served less than a year in jail for.[1]

Later life

Buck ended up living long enough to enjoy freedom again after his release from prison. He died in San Francisco on January 15, 1915 of natural causes, unlike his brothers, all of whom died violent deaths.[1][3]

References

- 1 2 3 Hattala, Doug (August 20, 2011). "Napa stagecoach robber stole his way into local lore". Napa Valley Register. Napa, CA: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- 1 2 "Bandit of Road Leaves His Cell". The Indianapolis Star. February 25, 1912. p. 39. Retrieved March 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Famous Napa Bandit Dies at Bay City". Napa Daily Journal. January 21, 1915. p. 1. Retrieved March 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lake County Historical Society

- Lake County Courthouse Museum Exhibit

- "Mount St. Helena and Robert Louis Stevenson State Park: A history and guide"