| |

| |

| Native name | |

|---|---|

| Namesake | George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham |

| Length | 414 |

| Width | 24 m (79 ft) |

| Postal code | D01 |

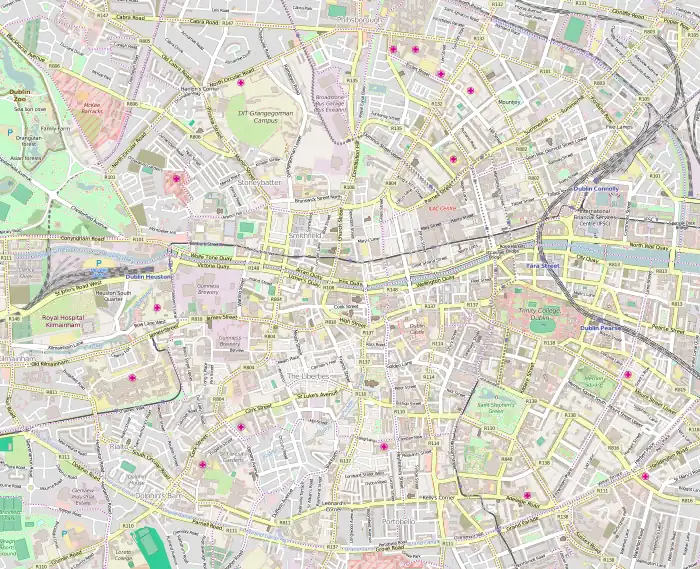

| Coordinates | 53°21′16″N 6°15′00″W / 53.35448238825031°N 6.24995156788307°W |

| north end | Summerhill |

| south end | Amiens Street |

Buckingham Street is a street in Dublin running from Summerhill to Amiens Street. It is divided into Buckingham Street Lower (south end) and Buckingham Street Upper (north end).

History

Buckingham Street was named for George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the time of its creation.[1] The upper section of the street is mentioned first around 1788, when plots of land on the new thoroughfare were laid out and offered with leases of 999 years. The street was initially planned to be 80 ft wide and 1300 ft long. It is possible that the land in this area was owned by Edward Stratford, 2nd Earl of Aldborough, who owned much of the land locally. It has been suggested that his membership of the Belles Lettres Literary Society inspired the naming of Bella Street, a small street off Upper Buckingham Street. From the 1790s, the street was developed by speculators.[2]

Following the economic and social effects of the Act of Union in 1801, property prices declined steeply between 1790 and 1840. By 1841, there were 19 buildings on the upper section of the street, with number 6 listed as a police station. By 1854, a large portion of the street remained undeveloped, 66 years after it was initially laid out. The street was largely tenements by 1890.[2]

Along with the neighbouring streets, Buckingham Street suffered deprivation throughout most of the 20th century. Between 1937 and 1939, a scheme of local authority flat complexes was built on the street, now known as the Killarney Street scheme. These were designed by Herbert George Simms. After the clearing of a number of the tenements on the street from number 11 to 17 a Dublin Corporation flat complex, Seán Treacy House, was built in the 1960s. Numbers 39 to 42 were demolished to make way for the Mountain View Court flats in the early 1970s, along with a number of Georgian houses on Summerhill. Mountain View Court was later demolished and the site redeveloped in 2004, and the Sean Tracey flats were similarly demolished and replaced beginning in 2009.[2]

A Christmas tree has been erected on this site each year since 1996 with a star memorialising a person who died from drug abuse, primarily heroin. In 2000 there were 124 stars on the tree. In 2000, the sculpture Home was unveiled on the street as a permanent memorial. It is by Leo Higgins, and is a gilded bronze flame within a limestone doorway.[3]

Architecture

One of the grandest buildings on the street is 9 Upper Buckingham Street, which was built in the 1810s by John Beresford for his son John Claudius Beresford. This house was later converted into a hospital, and was the first site of the Children's Health Ireland at Temple Street as St Joseph's Infirmary for Sick Children.[2][4]

The fire station on Lower Buckingham Street, which dates from 1899, is the oldest in a series of stations designed by the city architect, Charles J. McCarthy. Featuring an Italian Romanesque style, there was an attached alarm bell at Tara Street. The building now houses art studios.[5]

Buckingham Buildings

Upper Buckingham Street features one of the earliest Dublin Artisans' Dwellings Company schemes, known as Buckingham Buildings. The scheme was built on land donated by Francis Beatty, a resident at number 37.[2] Designed by Thomas Drew, work commenced in 1876, and consisted of two sections of purpose built tenement blocks. Block A was completed in 1878 and consisted of two storeys over basement. Block B was completed in 1879, and was a larger development of 4 storeys over basement with a large central staircase. The development was never popular with tenants, and many of the flats remained vacant for long periods of time. They were sold to Texacloth Ltd in 1979,[2] and later "coarsely" remodelled[6] in the early 1990s. It was renamed Buckingham Village in 1993.[2]

Notable residents

- John O'Donovan, lived at 36 Upper Buckingham Street from 1853 to 1861.[2]

- Bram Stoker lived in 19 Buckingham Street, from age 11 to 17. The house, which is derelict, had murals added to mark his association with the street.[7]

- Patrick Kelly, one of the children killed during the events of the Easter Rising, lived at 24 Buckingham Buildings.[8]

- John Claudius Beresford, lived at number 8 for a period[9][10]

References

- ↑ M'Cready, C. T. (1987). Dublin street names dated and explained. Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Carraig. p. 17. ISBN 1850680000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 O'Shea, Sinead; McManus, Ruth (2012). "Upper Buckingham Street: a microcosm of Dublin, 1788-2012". Studia Hibernica (38): 141–179. doi:10.3828/studia.38.141. ISSN 0081-6477. JSTOR 23645554. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Doherty, Neal (2015). The complete guide to the statues and sculptures of Dublin City. Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-909895-72-0. OCLC 907195579.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Buckingham Street Upper, Dublin, DUBLIN". Buildings of Ireland. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Clerkin, Paul (2001). Dublin street names. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 21. ISBN 0717132048.

- ↑ Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin : the city within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 182. ISBN 9780300109238.

- ↑ Byrne, Luke; O'Keeffe, Alan (19 October 2019). "The untold story of how inner-city Dublin shaped Dracula". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ↑ Hourihane, Ann Marie (22 March 2014). "Children of the revolution". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ "Beresford, John Claudius | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ↑ Campbell, John P. (1940). "Two Memorable Dublin Houses". Dublin Historical Record. pp. 141–155. Retrieved 25 September 2023.