ဗမာနွယ်ဖွား သြစတြေးလျ bamar nwe phwa sya hc-tyay-lya | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Western Australia | 8,704 |

| Victoria | 10,973 |

| New South Wales | 7,128 |

| Queensland | 3,172 |

| South Australia | 2000+ |

| Languages | |

| Australian English · Burmese · Karen · Hakha Chin · Shan · Kachin · Mon · Rakhine | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism · Christianity · Hinduism · Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Anglo-Burmese people, Bangladeshi Australians, Chinese Australians, Indian Australians, Rohingya people, Thai Australians | |

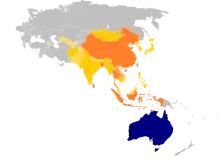

Burmese Australians (ဗမာနွယ်ဖွား သြစတြေးလျ) are Australian citizens or permanent residents who carry full or partial ancestry from Myanmar, also known as Burma, a country located in Southeast Asia. The majority ethnic group of Burma is the Bamar people but there are also numerous Burmese ethnic minorities.

Burma was historically ruled as a British colony throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was part of the British Raj (i.e., British India) at one point. The United Kingdom lost control of Burma to the Empire of Japan during World War II (1942), regained control over Burma in 1945, and was subsequently expelled from Burma in 1948 when the country became independent.

Like Burma, Australia was also historically a British colony, though Australia's indigenous population has largely been replaced by Anglo-Celtic Australians and other settler groups, whereas Anglo-Burmese people constitute a minority of Burma's native population.

Most Burmese Australians are of Bamar descent, though there are also many Sino-Burmese, Indo-Burmese and some Rohingya people in Australia.

History

For much of its post-colonial history, Myanmar (Burma) has been ruled by the Tatmadaw, its armed forces, which has exacerbated domestic political instability, especially in regions inhabited by ethnic minorities, such as the Karen, Shan, Rakhine, Mon, Chin and others. Unresolved political issues and grievances by ethnic armed organizations have fomented significant tensions and conflict with the military government.[2] Consequently, the ordinary Burmese have endured subjugation for decades under a series of military governments.[3] Many Burmese people were internally displaced in 2002 as a result.[3] Burmese people were either being forced to relocate or relocating by their own will.[3] Over a half million Burmese had escaped to neighbouring countries for safety. The government was accused of engaging in various many human rights violations, such as forced labour, forced displacement and persecution.[3]

Prior to Burmese arrival in Australia, this group of refugees were living in camps on the border between Burma and Thailand.[3] During their time in these camps Burmese refugees had experienced health problems and diseases, women in camps were exposed to violence, a lack of income and food security.[3]

Health

It was reported that a great number of the Burmese community have experienced certain health difficulties upon migrating to Australia.[4] Mental health conditions of the Burmese community in Australia upon migration has been examined and associated with factors of pre and post migration.[4] A study that was conducted indicated that a high number of participants reported various mental health distress this includes: PTSD (9%), anxiety (20%), depression (36%), and somatisation (37%).[4] This mental health factors were related to pre migration trauma and post migration difficulties.[4] It was reported that pre migration traumas linked to traumatisation symptoms whereas post migration had escalated symptoms of depression and anxiety.[4] Burmese migrants were greatly concerned about the difficulties of communication in Australia, and this hindering their ability to obtain job security and/or access to the right health services.[4] Furthermore, more worry was accentuated to educational opportunities and being away from family.[4]

A number of Burmese migrants who have settled in Australia have demonstrated Vitamin D deficiency as well as a number of infectious diseases.[5] Oral health is also not seen as a priority by many Burmese refugees in Australia due to the lack of oral health services in Burma.[5] It is also reported that the oral health of Burmese Australians is prone to further impacts if there is a rapid consumption of snacks and sugar in Australia.[5] Burmese migrants to Australia are also prone to chronic diseases.[5] Many refugees who were at the Thai-Burmese border camps before migrating to Australia have reported suffering from depression, and PTSD. Further members of the Burmese community are at risk of diabetes, high blood pressure and weight gain.[6]

Post-migration experiences

Access to services

After migrating to Australia, some Burmese people experienced various difficulties when settling in a new country.[7] One example of this is access to services, some Burmese Australians have reported difficulty when it came to knowing where and how to access a service, and the lack of interpreters has made them become reluctant when trying to access certain services.[7]

Fear of authorities

Burmese people had experienced much trauma with the due to the traumatic experiences in Burma with regards to the and the fear of Burmese military many Burmese people have developed a sense of fear towards authorities.[7] Many Burmese people had experienced much trauma due to the military dictatorship in Burma and the experiences of detention, ethnic discrimination, and persecution.[7] This has left a sense of fear, reluctance, and mistrust towards authorities in Australia such as police and government officials.[7]

Children

Certain Burmese Australian parents are struggling to understand their children who are experiencing two different cultures, thus reported to be making disciplining much more difficult for parents.[7]

Counselling

It is found that a vast number of the Burmese community in Australia experience much mental health issues due to the struggles and difficulties of both pre and post migration experiences, however due to the culture Burmese people are not familiar with seeking help or counselling from stranger or professional help.[7] Burmese culture and personality are seemed to influence their perspectives on mental health and the idea of support systems.[8]

Religious observance

Burmese Australians adhere to different religions including Buddhism, Christianity, or Islam. Religion is usually determined based on the ethnic group.[7] There are various religious organisations where Burmese Australians observe their religion and foster connectedness with the community.[7] Upon an influx of Burmans migrating to Australia, Buddhist monasteries were established. Burmese people also congregated in existing churches and there is a developing Burmese Muslim population in Southeast Melbourne.[7]

Demographics

According to the 2016 census the main languages spoken at home by Myanmar-born people in Australia is Burmese 40.5%, Karen languages 16.3%, English 12.3%, Hakha Chin 9.9%, other languages 20.5%.[9]

At the 2016 census the major religious affiliations for Myanmar-born were Baptist 31.0%, Buddhist 25.0%, Catholic 14.2%, Islam 10.7%, other religion 14.1%, no religion 2.9%.[9]

Locations

The Burmese population in Australia live in the major cities of Western Australia, Sydney, and Melbourne. In New South Wales, most Burmese Australians were reported to reside in the Western Sydney council areas of Cumberland 0.36% and Canterbury Bankstown 0.29%.[10] Sydney is also the home of the Australian Shan Community. There is also a fast-growing community of Burmese Australians in Adelaide, South Australia. Karen is considered to be the second most-spoken language in Mount Gambier.[11]

Culture

The Burmese association of Western Australia is one of the oldest organisations that was formed in 1965.[12] It originally was created to assist and support Burmese migrants but has moved to foster a broader purpose of creating understanding and relationships among other Australian communities through different programs and activities.[13] Burmese Australians frequently continue to consume traditional meals.[14] Food is considered an integral part of Burmese-Myanmar culture.[14] The Burmese association of Western Australia holds a monthly food fete that raises charity through the community and volunteer cooks.[13] This food fete enables people to try different types of the traditional cuisine by bringing the community together and celebrating multiculturalism.[13]

Gender roles

Gender roles in a Burmese Australian family is typically like that in their homeland.[5] Both men and women are involved in household tasks such as making food and shopping.[15] However, when larger festivities or gatherings are to take place, men are more typically responsible of cooking for these events.[5]

Religious and cultural influences

Burmese Australians are affiliated to various ethnic groups. These ethnic groups influence their religious and cultural and food practices. The Rohingya people who are primarily Muslim consume much more seafood and chilli.[16] They observe Islamic festivals of Ramadan and Eid.[5] The ethnic groups of Zomi and Chin have reported of eating a specific type of meat, whereas the Karenni group of people in Australia have reported eating vegetables.[5] In October the Buddhists celebrate their period of fasting with a festival in which many foods are consumed.[5] A harvest festival takes place in February whereby the Burmese community use the harvest food to make a festive glutinous rice dish called htamane.[5]

Food habits in Australia

The common foods of Burmese Australians are rice, curry, soups, stir fries and salads.[5] Many Burmese Australians have also reported consuming more meat and less vegetables in Australia.[5] Cooking techniques in the Burmese community include boiling, frying, fermentation[5] Young Burmese Australians have reported drinking soft drinks, juices as well as sweetened milk teas with jelly pieces have become popular.[5]

21st century media

The military takeover in Myanmar and the detention of Aung San Suu Kyi has shocked and dismayed the Burmese Australian community.[17] For some it brought back memories of military dictatorship and the experiences they had faced with the government before migration.[17] Many have also expressed their concerns and fears of their homeland going backwards, whilst others felt helpless for those in Myanmar and pray for the peace of their people and country.[17]

Notable people

See also

References

- 1 2 Australian Government - Department of Immigration and Border Protection. "Burmese Australians". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Archived 23 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine BURMESE Community Profile. Static1.squarespace.com,(2006).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 BURMESE Community Profile. Static1.squarespace.com. (2006). Retrieved 20 December 2021, from https://www.mcww.org.au/s/community-profile-burma.pdf Archived 23 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Schweitzer, R. D., Brough, M., Vromans, L., & Asic-Kobe, M. (2011). Mental health of newly arrived Burmese refugees in Australia: contributions of pre-migration and post-migration experience. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45 (4), 299-307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 -Tung, K., Chauk, L., & Taw, K. N. P. Burmese food and cultural profile: dietetic consultation guide.

- ↑ - Tung, K., Chauk, L., & Taw, K. N. P. Burmese food and cultural profile: dietetic consultation guide.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 People of Burma in Melbourne. Smrc.org.au. (2011). Retrieved 20 December 2021, from https://smrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/people-of-burma-in-melbourne.pdf Archived 3 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Way, Raymond Tint. "Burmese Culture, Personality and Mental Health". Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 19 (3): 275–282. doi:10.3109/00048678509158832. ISSN 0004-8674.

- 1 2 Myanmar Born Community Information Summary. Australian Government department of Human affairs. (2016). Retrieved 20 December 2016, from https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-myanmar.PDF Archived 3 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Introduction Burmese ancestry. CRC NSW. Multiculturalnsw.id.com.au. (2021). Retrieved 20 December 2021, from https://multiculturalnsw.id.com.au/multiculturalnsw/ancestry-introduction?COIID=238 Archived 13 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Karen overtakes Italian as second most spoken language in South Australian city". SBS News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ↑ The Burmese Association of Western Australia. Bawa.org.au. Retrieved 20 December 2021, from https://www.bawa.org.au/pages/services.html Archived 1 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 The Burmese Association of Western Australia. Bawa.org.au. Retrieved 20 December 2021, from https://www.bawa.org.au/pages/services.html Archived 1 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Myanmar's national dish has a cult following in Perth". SBS Food. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ↑ - Tung, K., Chauk, L., & Taw, K. N. P. Burmese food and cultural profile: dietetic consultation guide.

- ↑ Tung, K., Chauk, L., & Taw, K. N. P. Burmese food and cultural profile: dietetic consultation guide.

- 1 2 3 Handley, E. (2021). 'Going backwards': Australia's Burmese community fears return of military rule after Aung San Suu Kyi's arrest. Abc.net.au. Retrieved 11 January 2022, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-01/myanmar-burmese-rohingya-australia-community-react-military-coup/13108708 Archived 11 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ According to the local classification, South Caucasian peoples (Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Georgians) belong not to the European but to the "Central Asian" group, despite the fact that the territory of Transcaucasia has nothing to do with Central Asia and geographically belongs mostly to Western Asia.