| CN Tower | |

|---|---|

Tour CN | |

The CN Tower as seen from the Toronto City Centre Airport in September 2008, it is currently the world's 10th tallest free-standing structure[1][2] | |

| Alternative names | Canadian National Tower, Canada's National Tower |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1975[3] to 2007[4][I] | |

| Preceded by | Ostankino Tower |

| Surpassed by | Burj Khalifa |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Mixed use: Observation, telecommunications, attraction, restaurant |

| Address | 290 Bremner Boulevard Toronto, Ontario M5V 3L9 |

| Coordinates | 43°38′33.36″N 79°23′13.56″W / 43.6426000°N 79.3871000°W |

| Construction started | 6 February 1973[5][6] |

| Topped-out | 2 April 1975 |

| Completed | 1976 |

| Opening | 26 June 1976 |

| Cost | CA$63,000,000[6] |

| Owner | Canada Lands Company |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 553.3 m (1,815 ft) |

| Antenna spire | 96.1 m (315 ft) |

| Roof | 457.2 m (1,500 ft) |

| Top floor | 446.5 m (1,464.9 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 8 (7 in the main pod, 1 in the sky pod) |

| Lifts/elevators | 9[7] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | WZMH Architects: John Andrews, Webb Zerafa, Menkes Housden[7] |

| Website | |

| www | |

| References | |

| [5][6][7] | |

The CN Tower (French: Tour CN) is a 553.3 m-high (1,815.3 ft) concrete communications and observation tower in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[5][8] Completed in 1976, it is located in downtown Toronto, built on the former Railway Lands. Its name "CN" referred to Canadian National, the railway company that built the tower. Following the railway's decision to divest non-core freight railway assets prior to the company's privatization in 1995, it transferred the tower to the Canada Lands Company, a federal Crown corporation responsible for the government's real estate portfolio.

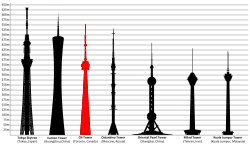

The CN Tower held the record for the world's tallest free-standing structure for 32 years, from 1975 until 2007, when it was surpassed by the Burj Khalifa, and was the world's tallest tower until 2009 when it was surpassed by the Canton Tower.[9][10][11] It is currently the tenth-tallest free-standing structure in the world and remains the tallest free-standing structure on land in the Western Hemisphere. In 1995, the CN Tower was declared one of the modern Seven Wonders of the World by the American Society of Civil Engineers. It also belongs to the World Federation of Great Towers.[12][13][7]

It is a signature icon of Toronto's skyline[14][15] and attracts more than two million international visitors annually.[7][16] It houses several observation decks, a revolving restaurant at some 350 metres (1,150 ft), and an entertainment complex.[17]

History

The original concept of the CN Tower was first conceived in 1968 when the Canadian National Railway wanted to build a large television and radio communication platform to serve the Toronto area, and to demonstrate the strength of Canadian industry and CN in particular. These plans evolved over the next few years, and the project became official in 1972.

The tower would have been part of Metro Centre (see CityPlace), a large development south of Front Street on the Railway Lands, a large railway switching yard that was being made redundant after the opening of the MacMillan Yard north of the city in 1965 (then known as Toronto Yard). Key project team members were NCK Engineering as structural engineer; John Andrews Architects; Webb, Zerafa, Menkes, Housden Architects; Foundation Building Construction; and Canron (Eastern Structural Division).[5][6][8]

As Toronto grew rapidly during the late 1960s and early 1970s, multiple skyscrapers were constructed in the downtown core, most notably First Canadian Place, which has Bank of Montreal's head offices. The reflective nature of the new buildings reduced the quality of broadcast signals, requiring new, higher antennas that were at least 300 m (980 ft) tall. The radio wire is estimated to be 102 metres (335 ft) long in 44 pieces, the heaviest of which weighs around 8 tonnes (8.8 short tons; 7.9 long tons).[18]

At the time, most data communications took place over point-to-point microwave links, whose dish antennas covered the roofs of large buildings. As each new skyscraper was added to the downtown, former line-of-sight links were no longer possible. CN intended to rent "hub" space for microwave links, visible from almost any building in the Toronto area.

The original plan for the tower envisioned a tripod consisting of three independent cylindrical "pillars" linked at various heights by structural bridges. Had it been built, this design would have been considerably shorter, with the metal antenna located roughly where the concrete section between the main level and the SkyPod lies today. As the design effort continued, it evolved into the current design with a single continuous hexagonal core to the SkyPod, with three support legs blended into the hexagon below the main level, forming a large Y-shape structure at the ground level.[8][19]

The idea for the main level in its current form evolved around this time, but the Space Deck (later renamed SkyPod) was not part of the plans until later. One engineer in particular felt that visitors would feel the higher observation deck would be worth paying extra for, and the costs in terms of construction were not prohibitive. Also around this time, it was realized that the tower could become the world's tallest free-standing structure to improve signal quality and attract tourists, and plans were changed to incorporate subtle modifications throughout the structure to this end.[8][19]

Construction

The CN Tower was built by Canada Cement Company (also known as the Cement Foundation Company of Canada at the time),[20] a subsidiary of Sweden's Skanska, a global project-development and construction group.

Construction began on February 6, 1973, with massive excavations at the tower base for the foundation. By the time the foundation was complete, 56,000 t (62,000 short tons; 55,000 long tons) of earth and shale were removed to a depth of 15 m (49.2 ft) in the centre, and a base incorporating 7,000 m3 (9,200 cu yd) of concrete with 450 t (496 short tons; 443 long tons) of rebar and 36 t (40 short tons; 35 long tons) of steel cable had been built to a thickness of 6.7 m (22 ft). This portion of the construction was fairly rapid, with only four months needed between the start and the foundation being ready for construction on top.[19]

To create the main support pillar, workers constructed a hydraulically raised slipform at the base. This was a fairly unprecedented engineering feat on its own, consisting of a large metal platform that raised itself on jacks at about 6 m (20 ft) per day as the concrete below set. Concrete was poured Monday to Friday (not continuously) by a small team of people until February 22, 1974, at which time it had already become the tallest structure in Canada, surpassing the recently built Inco Superstack in Sudbury, built using similar methods.

The tower contains 40,500 m3 (53,000 cu yd) of concrete, all of which was mixed on-site in order to ensure batch consistency. Through the pour, the vertical accuracy of the tower was maintained by comparing the slip form's location to massive plumb bobs hanging from it, observed by small telescopes from the ground. Over the height of the tower, it varies from true vertical accuracy by only 29 mm (1.1 in).[8][19]

In August 1974, construction of the main level commenced. Using 45 hydraulic jacks attached to cables strung from a temporary steel crown anchored to the top of the tower, twelve giant steel and wooden bracket forms were slowly raised, ultimately taking about a week to crawl up to their final position. These forms were used to create the brackets that support the main level, as well as a base for the construction of the main level itself. The Space Deck (currently named SkyPod) was built of concrete poured into a wooden frame attached to rebar at the lower level deck, and then reinforced with a large steel compression band around the outside.[19]

While still under construction, the CN Tower officially became the world's tallest free-standing structure on March 31, 1975.[3]

The antenna was originally to be raised by crane as well, but, during construction, the Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane helicopter became available when the United States Army sold one to civilian operators. The helicopter, named "Olga", was first used to remove the crane, and then flew the antenna up in 36 sections.

The flights of the antenna pieces were a minor tourist attraction of their own, and the schedule was printed in local newspapers. Use of the helicopter saved months of construction time, with this phase taking only three and a half weeks instead of the planned six months. The tower was topped-off on April 2, 1975, after 26 months of construction, officially capturing the height record from Moscow's Ostankino Tower, and bringing the total mass to 118,000 t (130,000 short tons; 116,000 long tons).

Two years into the construction, plans for Metro Centre were scrapped, leaving the tower isolated on the Railway Lands in what was then a largely abandoned light-industrial space. This caused serious problems for tourists to access the tower. Ned Baldwin, project architect with John Andrews, wrote at the time that "All of the logic which dictated the design of the lower accommodation has been upset," and that "Under such ludicrous circumstances Canadian National would hardly have chosen this location to build."[21]

Phases of construction

Constructing the base, July 1973

Constructing the base, July 1973 Brackets being raised, August 1974

Brackets being raised, August 1974 Helicopter lifting part of antenna, March 1975

Helicopter lifting part of antenna, March 1975.jpg.webp) Main pod construction, April 1975

Main pod construction, April 1975 Nearing completion, December 1975

Nearing completion, December 1975 Two months after opening, August 1976

Two months after opening, August 1976

Opening

The CN Tower opened on June 26, 1976.[22] The construction costs of approximately CA$63 million ($287 million in 2021 dollars)[23] were repaid in fifteen years.[24]

From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, the CN Tower was practically the only development along Front Street West; it was still possible to see Lake Ontario from the foot of the CN Tower due to the expansive parking lots and lack of development in the area at the time. As the area around the tower was developed, particularly with the completion of the Metro Toronto Convention Centre (north building) in 1984 and SkyDome in 1989 (renamed Rogers Centre in 2005), the former Railway Lands were redeveloped and the tower became the centre of a newly developing entertainment area. Access was greatly improved with the construction of the SkyWalk in 1989, which connected the tower and SkyDome to the nearby Union Station railway and subway station, and, in turn, to the city's Path underground pedestrian system. By the mid-1990s, it was the centre of a thriving tourist district. The entire area continues to be an area of intense building, notably a boom in condominium construction in the first quarter of the 21st century, as well as the 2013 opening of the Ripley's Aquarium by the base of the tower.[7][8][19]

Early years

When the CN Tower opened in 1976, there were three public observation points: the SkyPod (then known as the Space Deck) that stands at 447 m (1,467 ft), the Indoor Observation Level (later named Indoor Lookout Level) at 346 m (1,135 ft), and the Outdoor Observation Terrace (at the same level as the Glass Floor) at 342 m (1,122 ft).[7][19] One floor above the Indoor Observation Level was the Top of Toronto Restaurant, which completed a revolution once every 72 minutes.[25]

The tower would garner worldwide media attention when stuntman Dar Robinson jumped off the CN Tower on two occasions in 1979 and 1980. The first was for a scene from the movie Highpoint, in which Robinson received CA$250,000 ($885,000 in 2021 dollars)[23] for the stunt. The second was for a personal documentary. The first stunt had him use a parachute which he deployed three seconds before impact with the ground, while the second one used a wire decelerator attached to his back.[26]

On June 26, 1986, the tenth anniversary of the tower's opening, high-rise firefighting and rescue advocate Dan Goodwin, in a sponsored publicity event, used his hands and feet to climb the outside of the tower, a feat he performed twice on the same day. Following both ascents, he used multiple rappels to descend to the ground.[27]

From 1985 to 1992, the CN Tower basement level hosted the world's first flight simulator ride, Tour of the Universe. The ride was replaced in 1992 with a similar attraction entitled "Space Race." It was later dismantled and replaced by two other rides in 1998 and 1999.

The 1990s and 2000s

A glass floor at an elevation of 342 m (1,122 ft) was installed in 1994.[19] Canadian National Railway sold the tower to Canada Lands Company prior to privatizing the company in 1995, when it divested all operations not directly related to its core freight shipping businesses. The tower's name and wordmark were adjusted to remove the CN railways logo, and the tower was renamed Canada's National Tower (from Canadian National Tower),[28] though the tower is commonly called the CN Tower.

Further changes were made from 1997 to January 2004: TrizecHahn Corporation managed the tower and instituted several expansion projects including a CA$26 million entertainment expansion, the 1997 addition of two new elevators (to a total of six) and the consequential relocation of the staircase from the north side leg to inside the core of the building, a conversion that also added nine stairs to the climb. TrizecHahn also owned the Willis Tower (Sears Tower at the time) in Chicago approximately at the same time.

In 2007, light-emitting diode (LED) lights replaced the incandescent lights that lit the CN Tower at night. This was done to take advantage of the cost savings of LED lights over incandescent lights. The colour of the LED lights can change, compared to the constant white colour of the incandescent lights. On September 12, 2007, Burj Khalifa, then under construction and known as Burj Dubai, surpassed the CN Tower as the world's tallest free-standing structure.[29] In 2008, glass panels were installed in one of the CN Tower elevators, which established a world record (346 m) for highest glass floor panelled elevator in the world.

2010s: EdgeWalk

On August 1, 2011, the CN Tower opened the EdgeWalk, an amusement in which thrill-seekers can walk on and around the roof of the main pod of the tower at 356 m (1,168.0 ft), which is directly above the 360 Restaurant.[30] It is the world's highest full-circle, hands-free walk. Visitors are tethered to an overhead rail system and walk around the edge of the CN Tower's main pod above the 360 Restaurant on a 1.5-metre (4.9 ft) metal floor.[31] The attraction is closed throughout the winter and during periods of electrical storms and high winds.

One of the notable guests who visited EdgeWalk was Canadian comedian Rick Mercer, featured as the first episode of the ninth season of his CBC Television news satire show, Rick Mercer Report. There, he was accompanied by Canadian pop singer Jann Arden. The episode first aired on April 10, 2013.[32]

Pan Am Games

The tower and surrounding areas were prominent in the 2015 Pan American Games production. In the opening ceremony, a pre-recorded segment featured track-and-field athlete Bruny Surin passing the flame to sprinter Donovan Bailey on the EdgeWalk and parachuting into Rogers Centre. A fireworks display off the tower concluded both the opening and closing ceremonies.

Canada 150

On July 1, 2017, as part of the nationwide celebrations for Canada 150, which celebrated the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, fireworks were once again shot from the tower in a five-minute display coordinated with the tower lights and music broadcast on a local radio station.

Closures

- The CN Tower was closed on September 11, 2001 following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

- The CN Tower was closed during the G20 summit on June 26–27, 2010, for security reasons, given its proximity to the Metro Toronto Convention Centre and ongoing citywide protests and riots.

- The CN Tower was closed from 2020 to 2021 due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions throughout Ontario.

- The CN Tower was closed on December 16, 2021, due to glass falling off from heavy winds.[33]

Structure

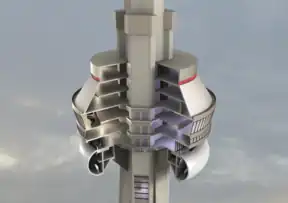

The CN Tower consists of several substructures. The main portion of the tower is a hollow concrete hexagonal pillar containing the stairwells and power and plumbing connections. The tower's six elevators are located in the three inverted angles created by the Tower's hexagonal shape (two elevators per angle). Each of the three elevator shafts is lined with glass, allowing for views of the city as the glass-windowed elevators make their way through the tower. The stairwell was originally located in one of these angles (the one facing north), but was moved into the central hollow of the tower; the tower's new fifth and sixth elevators were placed in the hexagonal angle that once contained the stairwell. On top of the main concrete portion of the tower is a 102 m (334.6 ft) tall metal broadcast antenna, carrying television and radio signals. There are three visitor areas: the Glass Floor and Outdoor Observation Terrace, which are both located at an elevation of 342 m (1,122 ft), the Indoor Lookout Level (formerly known as "Indoor Observation Level") located at 346 m (1,135 ft), and the higher SkyPod (formerly known as "Space Deck") at 446.5 m (1,465 ft),[34] just below the metal antenna. The hexagonal shape is visible between the two highest areas; however, below the main deck, three large supporting legs give the tower the appearance of a large tripod.

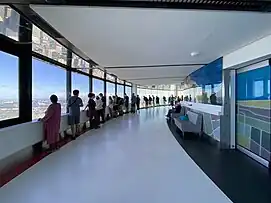

The main deck level has seven storeys, some of which are open to the public. Below the public areas—at 338 m (1,108.9 ft)—is a large white donut-shaped radome containing the structure's UHF transmitters. The glass floor and outdoor observation deck are at 342 m (1,122.0 ft). The glass floor has an area of 24 m2 (258 sq ft) and can withstand a pressure of 4.1 megapascals (595 psi). The floor's thermal glass units are 64 mm (2.5 in) thick, consisting of a pane of 25 mm (1.0 in) laminated glass, 25 mm (1.0 in) airspace and a pane of 13 mm (0.5 in) laminated glass. In 2008, one elevator was upgraded to add a glass floor panel, believed to have the highest vertical rise of any elevator equipped with this feature.[35] The Horizons Cafe and the lookout level are at 346 m (1,135.2 ft). The 360 Restaurant, a revolving restaurant that completes a full rotation once every 72 minutes, is at 351 m (1,151.6 ft). When the tower first opened, it also featured a disco named Sparkles (at the Indoor Observation Level), billed as the highest disco and dance floor in the world.[36]

The SkyPod was once the highest public observation deck in the world until it was surpassed by the Shanghai World Financial Center in 2008.[37]

A metal staircase reaches the main deck level after 1,776 steps,[7][38] and the SkyPod 100 m (328 ft) above after 2,579 steps; it is the tallest metal staircase on Earth. These stairs are intended for emergency use only except for charity stair-climb events two times during the year.[39][40] The average climber takes approximately 30 minutes to climb to the base of the radome, but the fastest climb on record is 7 minutes and 52 seconds in 1989 by Brendan Keenoy, an Ontario Provincial Police officer.[40] In 2002, Canadian Olympian and Paralympic champion Jeff Adams climbed the stairs of the tower in a specially designed wheelchair. The stairs were originally on one of the three sides of the tower (facing north), with a glass view, but these were later replaced with the third elevator pair and the stairs were moved to the inside of the core.[38] Top climbs on the new, windowless stairwell used since around 2003 have generally been over ten minutes.[41]

.jpg.webp) Inside 360 Restaurant

Inside 360 Restaurant Main Observation Level after renovation in 2018

Main Observation Level after renovation in 2018 Cross-section of Main Pod

Cross-section of Main Pod.jpg.webp) Skypod

Skypod Terrace Level glass floor

Terrace Level glass floor View through glass floor

View through glass floor Gift shop in 2023

Gift shop in 2023 Ground view looking up at the CN Tower.

Ground view looking up at the CN Tower.

Architects

- WZMH Architects

- John Hamilton Andrews

- Webb Zerafa

- Menkes Housden with the help of Edward R. Baldwin

Falling ice danger

A freezing rain storm on March 2, 2007, resulted in a layer of ice several centimetres thick forming on the side of the tower and other downtown buildings. The sun thawed the ice, then winds of up to 90 km/h (56 mph) blew some of it away from the structure. There were fears that cars and windows of nearby buildings would be smashed by large chunks of ice. In response, police closed some streets surrounding the tower. During morning rush hour on March 5 of the same year, police expanded the area of closed streets to include the Gardiner Expressway 310 m (1,017 ft) away from the tower as increased winds blew the ice farther, as far north as King Street West, 490 m (1,608 ft) away, where a taxicab window was shattered. Subsequently, on March 6, 2007, the Gardiner Expressway reopened after winds abated.[42]

On April 16, 2018, falling ice from the CN Tower punctured the roof of the nearby Rogers Centre stadium, causing the Toronto Blue Jays to postpone the game that day to the following day as a doubleheader; this was the third doubleheader held at the Rogers Centre. On April 20 of the same year, the CN Tower reopened.[43]

Safety features

In August 2000, a fire broke out at the Ostankino Tower in Moscow, killing three people and causing extensive damage. The fire was blamed on poor maintenance and outdated equipment. The failure of the fire-suppression systems and the lack of proper equipment for firefighters allowed the fire to destroy most of the interior and sparked fears the tower might even collapse.

The Ostankino Tower was completed nine years before the CN Tower and is only 13 m (43 ft) shorter.[44] The parallels between the towers led to some concern that the CN Tower could be at risk of a similar tragedy. However, Canadian officials subsequently stated that it is "highly unlikely" that a similar disaster could occur at the CN Tower, as it has important safeguards that were not present in the Ostankino Tower. Specifically, officials cited:

- the fireproof building materials used in the tower's construction,

- frequent and stringent safety inspections,

- an extensive sprinkler system,

- a 24-hour emergency monitoring operation,

- two 68,160-litre (15,000-imperial gallon; 18,006-US gallon) water reservoirs at the top, which are automatically replenished,

- a fire hose at the base of the structure capable of sending 2,725 L/min (720 U.S. gal/min; 599 imp gal/min) to any location in the tower,

- a ban on natural gas appliances anywhere in the tower (including the restaurant in the main pod),

- an elevator that can be used during a fire as it runs up the outside of the building and can be powered by three emergency generators at the base of the structure (unlike the elevator at the Ostankino Tower, which malfunctioned).[45]

Officials also noted that the CN Tower has an excellent safety record, although there was an electrical fire in the antennas on August 16, 2017 — the tower's first fire.[45][46][47][48] Moreover, other supertall structures built between 1967 and 1976 — such as the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower), the World Trade Center (until its destruction on September 11, 2001), the Fernsehturm Berlin, the Aon Center, 875 North Michigan Avenue (formerly the John Hancock Center), and First Canadian Place — also have excellent safety records, which suggests that the Ostankino Tower accident was a rare safety failure, and that the likelihood of similar events occurring at other supertall structures is extremely low.

Lighting

The CN Tower was originally lit at night with incandescent lights, which were removed in 1997 because they were inefficient and expensive to repair. In June 2007, the tower was outfitted with 1,330 super-bright LED lights inside the elevator shafts, shooting over the main pod and upward to the top of the tower's mast to light the tower from dusk until 2 a.m. The official opening ceremony took place on June 28, 2007, before the Canada Day holiday weekend.

The tower changes its lighting scheme on holidays and to commemorate major events. After the 95th Grey Cup in Toronto, the tower was lit in green and white to represent the colours of the Grey Cup champion Saskatchewan Roughriders.[49] From sundown on August 27, 2011, to sunrise the following day, the tower was lit in orange, the official colour of the New Democratic Party (NDP), to commemorate the death of federal NDP leader and leader of the official opposition Jack Layton.[50] When former South African president Nelson Mandela died, the tower was lit in the colours of the South African flag. When former federal finance minister under Stephen Harper's Conservatives Jim Flaherty died, the tower was lit in green to reflect his Irish Canadian heritage. On the night of the attacks on Paris on November 13, 2015, the tower displayed the colours of the French flag. On June 8, 2021, the tower displayed the colours of the Toronto Maple Leafs' archrivals Montreal Canadiens after they advanced to the semifinals of 2021 Stanley Cup playoffs.[51] The CN Tower was lit in the colours of the Ukrainian flag during the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022.

Programmed remotely from a desktop computer with a wireless network interface controller in Burlington, Ontario, the LEDs use less energy to light than the previous incandescent lights (10% less energy than the dimly lit version and 60% less than the brightly lit version).[52] The estimated cost to use the LEDs is $1,000 per month.

During the spring and autumn bird migration seasons, the lights are turned off to comply with the voluntary Fatal Light Awareness Program, which "encourages buildings to dim unnecessary exterior lighting to mitigate bird mortality during spring and summer migration."[53]

| Date | Colour | Occasion |

|---|---|---|

| Ongoing | Red and White | Top of the hour CN Tower light show |

| January 26 | Light Blue and Yellow | World Alzheimer Day |

| February 4 | Orange and Blue | World Cancer Day |

| February 14 | Red | Valentine's Day |

| March 17 | Green | Saint Patrick's Day |

| March 21–June 20 | Decreased Lighting | Bird Migration - Lighting is decreased during spring bird migration |

| September 23–December 20 | Decreased Lighting | Bird Migration - Lighting is decreased during autumn bird migration |

| December | Red and Green | Season's Greetings |

| December 1 | Red | World AIDS Day |

| December 6 | Purple | White Ribbon Day |

| December 10 | Yellow | Human Rights Day |

| December 21 | Blue and White | First Day of Winter |

| December 31 | Countdown to 2025 and Light Show | New Year's Eve |

Height comparisons

The CN Tower is the tallest freestanding structure in the Western Hemisphere. As of 2013, there were two other freestanding structures in the Western Hemisphere exceeding 500 m (1,640.4 ft) in height: the Willis Tower in Chicago, which stands at 527 m (1,729.0 ft) when measured to its pinnacle, and One World Trade Center in New York City, which has a pinnacle height of 541.33 m (1,776.0 ft), or approximately 12 m (39.4 ft) shorter than the CN Tower. Due to the symbolism of the number 1776 (the year of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence), the height of One World Trade Center is unlikely to be increased. The proposed Chicago Spire was expected to exceed the height of the CN Tower, but its construction was halted early due to financial difficulties amid the Great Recession, and was eventually cancelled in 2010.[54]

Height distinction debate

"World's Tallest Tower" title

Guinness World Records has called the CN Tower "the world's tallest self-supporting tower" and "the world's tallest free-standing tower".[55][56] Although Guinness did list this description of the CN Tower under the heading "tallest building" at least once,[56] it has also listed it under "tallest tower", omitting it from its list of "tallest buildings."[55] In 1996, Guinness changed the tower's classification to "World's Tallest Building and Freestanding Structure". Emporis and the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat both listed the CN Tower as the world's tallest free-standing structure on land, and specifically state that the CN Tower is not a true building, thereby awarding the title of world's tallest building to Taipei 101, which is 44 m (144 ft) shorter than the CN Tower.[13][57] The issue of what was tallest became moot when Burj Khalifa, then under construction, exceeded the height of the CN Tower in 2007 (see below).

Although the CN Tower contains a restaurant, a gift shop and multiple observation levels, it does not have floors continuously from the ground, and therefore it is not considered a building by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) or Emporis. CTBUH defines a building as "a structure that is designed for residential, business, or manufacturing purposes. An essential characteristic of a building is that it has floors."[57] The CN Tower and other similar structures—such as the Ostankino Tower in Moscow, Russia; the Oriental Pearl Tower in Shanghai, China; The Strat in Las Vegas, Nevada, United States; and the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France—are categorized as "towers", which are free-standing structures that may have observation decks and a few other habitable levels, but do not have floors from the ground up. The CN Tower was the tallest tower by this definition until 2010 (see below).[13]

Taller than the CN Tower are numerous radio masts and towers, which are held in place by guy-wires, the tallest being the KVLY-TV mast in Blanchard, North Dakota, in the United States at 628 m (2,060 ft) tall, leading to a distinction between these and "free-standing" structures. Additionally, the Petronius Platform stands 610 m (2,001 ft) above its base on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico near the Mississippi River Delta, but only the top 75 m (246 ft) of this oil and natural gas platform are above water, and the structure is thus partially supported by its buoyancy. Like the CN Tower, none of these taller structures are commonly considered buildings.

On September 12, 2007, Burj Khalifa, which is a hotel, residential and commercial building in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (formerly known as Burj Dubai before opening), passed the CN Tower's 553.33-m[8] height. The CN Tower held the record of the tallest freestanding structure on land for over 30 years.[29]

After Burj Khalifa had been formally recognized by the Guinness World Records as the world's tallest freestanding structure, Guinness re-certified CN Tower as the world's tallest freestanding tower.[58] The tower definition used by Guinness was defined by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat as 'a building in which less than 50% of the construction is usable floor space'. Guinness World Records editor-in-chief Craig Glenday announced that Burj Khalifa was not classified as a tower because it has too much usable floor space to be considered to be a tower.[59] CN Tower still held world records for highest above ground wine cellar (in 360 Restaurant) at 351 m, highest above ground restaurant at 346 m (Horizons Restaurant),[60] and tallest free-standing concrete tower during Guinness's recertification. The CN Tower was surpassed in 2009 by the Canton Tower in Guangzhou, China, which stands at 604 m (1,982 ft) tall, as the world's tallest tower; which in turn was surpassed by the Tokyo Skytree in 2011, which currently is the tallest tower at 634.0 m (2,080.1 ft) in height.[11][61] The CN Tower, as of 2022, stands as the tenth-tallest free-standing structure on land, remains the tallest free-standing structure in the Western Hemisphere, and is the third-tallest tower.[1][62][63]

Height records

Since its construction, the tower has gained the following world height records:[3]

| Record | Owner | Value | Time period | Succeeded by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World's tallest free-standing structure | CN Tower | 553.33 metres (1,815.4 ft) | March 31, 1975 to September 12, 2007 | Burj Khalifa |

| World's tallest tower | CN Tower | 553.33 metres (1,815.4 ft) | 1975 to 2009 | Canton Tower |

| World's highest public observation gallery | SkyPod | 447 metres (1,467 ft) | ||

| World's highest glass floor panelled elevator | CN Tower | 346 metres (1,135 ft) | 2008 to present | — |

| World's longest metal staircase | CN Tower | 2,579 steps | ||

| World's highest glass floor | CN Tower | 342 metres (1,122 ft) | 2008 to July 2, 2009 | Willis Tower |

| World's highest and largest revolving restaurant | 360 Restaurant | 351 metres (1,152 ft) | ||

| World's highest bar | Horizons Restaurant | 346 metres (1,135 ft) | September 21, 2009 to present | — |

| World's highest wine cellar | 360 Restaurant | 351 metres (1,152 ft) |

Use

The CN Tower has been and continues to be used as a communications tower for a number of different media and by numerous companies.[64]

Television broadcasters

| VHF | UHF | Virtual | Callsign | Affiliation | Branding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | — | 9.1 | CFTO-DT | CTV | CTV Toronto |

| — | 19 | 19.1 | CICA-DT | TVO | TVO |

| — | 20 | 5.1 | CBLT-DT | CBC Television | CBC Toronto |

| — | 25 | 25.1 | CBLFT-DT | Ici Radio-Canada Télé | ICI Ontario |

| — | 40 | 40.1 | CJMT-DT | Omni Television | Omni.2 |

| — | 41 | 41.1 | CIII-DT-41 | Global | Global Toronto |

| — | 44 | 57.1 | CITY-DT | Citytv | Citytv Toronto |

| — | 47 | 47.1 | CFMT-DT | Omni Television | Omni.1 |

Source: Vividcomm[64]

Radio

There is no AM broadcasting from the CN Tower.[65] The FM transmitters are situated in a 102 m-tall (335 ft) metal broadcast antenna, on top of the main concrete portion of the tower at an elevation above 446.5 m (1,465 ft).

| Frequency | kW | Callsign[66] | Affiliation/Owner | Branding | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91.1 MHz | 40 | CJRT | Independent; Public | JAZZ.FM91 | Jazz |

| 94.1 MHz | 38 | CBL | Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | CBC Music | Non-commercial; classical; jazz |

| 97.3 MHz | 28.9 | CHBM | Stingray Group | boom 97.3 | Classic hits |

| 98.1 MHz | 44 | CHFI | Rogers Sports & Media | 98.1 CHFI | Adult contemporary |

| 99.9 MHz | 40 | CKFM | Bell Media | Virgin Radio 99.9FM | Top 40/Contemporary hits |

| 100.7 MHz | 4 | CHIN | CHIN Radio/TV International | CHIN Radio | Primarily in Italian and Portuguese |

| 102.1 MHz | 35 | CFNY | Corus Entertainment | 102.1 the Edge | Alternative rock |

| 104.5 MHz | 40 | CHUM | Bell Media | 104.5 CHUM FM | Hot adult contemporary |

| 107.1 MHz | 40 | CILQ | Corus Entertainment | Classic Rock Q 107 | Mainstream rock |

Source: Vividcomm[64]

Communications

- Bell Canada

- Toronto Transit Commission

- Amateur radio repeaters "2-Tango" (VHF) and "4-Tango" (440/70 cm UHF)—owned and operated by the Toronto FM Communications Society, under callsign VE3TWR[67]

In popular culture

The CN Tower has been featured in numerous films, television shows, music recording covers, and video games. The tower also has its own official mascot, which resembles the tower itself.[68]

- Highpoint is a Canadian 1982 action film starring Richard Harris, Christopher Plummer and Beverly D'Angelo. It features a shot of stuntman Dar Robinson jumping off of the CN Tower in 1979.[26]

- Views is a 2016 studio album released on April 29, 2016 by Canadian rapper Drake. The cover artwork features Drake sitting atop the CN Tower in Toronto.[69] Drake appeared significantly larger than life-size on the cover, and the CN Tower's Twitter account later confirmed it to be photo edited.[70]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Compare Data: Results". The Skyscraper Center.

- ↑ "CN Tower retains world record as tallest 'tower'". Toronto Star. September 22, 2009. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "The Tower, according to Guinness World Records". CN Tower. Archived from the original on November 18, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ "CN Tower no longer world's tallest". Toronto Star. September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "CN Tower". SkyscraperPage.

- 1 2 3 4 "Emporis building ID 112537". Emporis. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Facts and visitor information on the CN Tower in Canada". The World Federation of Great Towers. Archived from the original on September 29, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Canada's Wonder of the World". CN Tower. Archived from the original on July 23, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ↑ "The world's tallest structures through history". The Daily Telegraph. London. April 20, 2017. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ↑ "Modern World Wonders-CN Tower". www.theworldwonders.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Mollins, Julie (April 9, 2008). "CN Tower's glass-floored lift not for faint-hearted". Reuters.

- 1 2 "Canton Tower, Guangzhou". SkyscraperPage.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Matt (March 3, 2017). "Seven Wonders of the World". ThoughtCo. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "The Seven Wonders of the Modern World". Infoplease.com. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ↑ Plummer, Kevin (September 4, 2007). "The CN Tower is Dead. Long Live The CN Tower!". The Torontoist. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ↑ CN Tower celebrates 30th birthday, Broadcast News/canada.com, June 26, 2006 Archived June 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "World Wonders and Facts at a Glance". CN Tower. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ↑ "CN Tower | building, Toronto, Ontario, Canada | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ↑ Sienkiewicz, Alexandra (August 16, 2017). "Here's what the CN Tower was intended for, before the glass floor and EdgeWalk". CBC.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 TrizecHahn. "A Brief Overview of the CN Tower". Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ↑ Barr, Elinor (2015). Swedes in Canada: Invisible Immigrants. University of Toronto Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1442613744.

- ↑ Fulford, Robert (March 13, 1996). Accidental city: the transformation of Toronto. MacFarlane, Walter & Ross. p. 32. ISBN 978-0395773079.

- ↑ Botelho-Urbanski, Jessica (June 25, 2016). "CN Tower celebrates 40 years as a tourist magnet and lightning rod". Toronto Star. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- 1 2 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Building the CN Tower". DOZR. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ↑ "General Information" (PDF). CN Tower. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- 1 2 Kupferman, Steve (February 26, 2010). "Man Jumps From CN Tower With No Parachute (Thirty Years Ago)". Torontoist. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ↑ Goodwin, Dan. "Dan Goodwin's Building Climbs". Skyscraperdefense.com. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ↑ ""Canada's Wonder of the World"". CN Tower: Plan Your Visit > Who We Are. CN Tower - Canada Lands Company. Archived from the original on July 23, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- 1 2 "CN Tower dethroned by Dubai building". CBC News. September 12, 2007. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ "New CN Tower attraction offers a walk on the outside". Toronto Star. May 9, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Toronto's Most Extreme Attraction". CN Tower. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

It is the world's highest full circle hands-free walk on a 5 ft (1.5 metres) wide ledge encircling the top of the tower's main pod, 356m/1168ft (116 storeys) above the ground.

- ↑ "Season 9 - Episode 1". CBC Television. Rick Mercer Report. April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Glass falls from CN Tower as heavy winds hit Toronto". CBC. December 16, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ↑ "CN Tower". SkyscraperPage.com. Skyscraper Source Media. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ Canadian Press (April 9, 2008). "CN Tower's glass-floor elevator aims for record". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on October 18, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2008. Both linked pages include a video of the elevator with glass floor in operation.

- ↑ Malcolm, Andrew. "A New High for Disco in Toronto's Tower", The New York Times, October 10, 1979. Accessed February 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Shanghai World Financial Center". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- 1 2 "Man climbs CN Tower steps in wheelchair". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. September 27, 2002. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ↑ "18th Annual Canada Life CN Tower Climb for WWF Canada". World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Canada. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- 1 2 Ferenc, Leslie (October 15, 2007). "Corporate climbers ready to step up for charity". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ "21st Annual Canada Life CN Tower Climb for WWF-Canada". WWF. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Video: Falling CN Tower Ice". CITY-DT. March 2, 2007. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ↑ "CN Tower, closed since Monday due to falling ice concerns, reopens". cbc.ca. April 20, 2018.

- ↑ Womackin, Helen (August 29, 2000). "Fire in 1,800ft TV tower adds to Russians' feeling of doom". The Independent.

- 1 2 "What if the CN Tower Caught Fire?". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. November 10, 2000. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ↑ Doherty, Brennan (August 16, 2017). "Fire crews tackle smouldering fire at CN Tower antenna". Toronto Star. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Amara (August 16, 2017). "Fire inside broadcasting antenna atop CN Tower now extinguished". CBC News. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, Codi (August 16, 2017). "CN Tower open for business after early morning fire in antenna mast". CTV Toronto News. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Highlighting the CN Tower — Testing of Innovative Illumination Technology Begins Early June 2007" (PDF) (Press release). CN Tower. June 28, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Jack Layton's 'passion, civility' honoured at funeral". CBC News. August 27, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ↑ TSN.ca Staff (June 8, 2021). "Toronto's CN Tower to be lit in Canadiens colours". TSN. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ↑ Black, Debra (May 30, 2007). "Come Canada Day, CN Tower will once again light up the night". Toronto Star. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ↑ "CN Tower in Toronto receives LED lighting treatment". LEDs Magazine. June 18, 2007. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Calatrava Dances onto a New Stage". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on February 13, 2011.

- 1 2 McWhirter, Norris (1981). Guinness Book of World Records 1982. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. p. 704. ISBN 978-0-8069-0225-8. OCLC 7902975. Reference is on page 275.

- 1 2 "Guinness Book of World Records 2005 – Science and Technology << Buildings". Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- 1 2 "CTBUH Tall Building Database". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ↑ Daubs, Katie (September 22, 2009). "CN tower now the 'world's tallest freestanding tower'". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ "CN Tower remains world's tallest tower, Guinness says". National Post. September 18, 2009.

- ↑ "CN Tower still world's tallest: Guinness". CBC News. September 18, 2009.

- ↑ Owen, James (November 29, 2011). "World's Tallest Tower Rises in Tokyo". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Where Is The Largest Tower In The World?". worldatlas.com. October 4, 2018.

- ↑ "The CN Tower, once the world's tallest, soon won't even make the top 10". National Post. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Martin, M.J. (September 25, 2019). "CN Tower: RF Telecom". Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ↑ "AM Query & AM List Results". Federal Communications Commission – Audio Division. April 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ "FM Query & FM List Results". Federal Communications Commission – Audio Division. April 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Toronto ARES Channels". October 26, 2005. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- ↑ Fearon, Emily (July 19, 2017). "A new mascot for the CN Tower is a mini CN Tower". Toronto Star.

- ↑ "Drake's towering view of The 6 | Toronto Star". thestar. April 26, 2016. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ↑ @TourCNTower (April 25, 2016). "Proud Torontonian @Drake at the top of CN Tower with the help of some photoshop magic! #photshopped #notreallythere" (Tweet). Archived from the original on April 28, 2016 – via Twitter.

External links

- Official website

- CBC Archives – CN Tower opens to the public. (Multimedia)

- Edgewalk

- The Design, Engineering and Construction of the CN Tower – 1972 through to 1976

- A visual construction history of the CN Tower – at 40th year anniversaries

- How the CN Tower was Built - Art Of Engineering (YouTube documentary)