Candle making was developed independently in many places around the world.[1]

Dipped candles made from tallow were made by the Romans beginning about 1000 BC. Evidence for candles made from whale fat in China dates back to the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE).[2] In India, wax from boiling cinnamon was used for temple candles.[2]

Candles were primarily made from tallow and beeswax in ancient times, but have been made from spermaceti (from sperm whales), purified animal fats (stearin), and paraffin wax in recent centuries.[1]

Antiquity

The early Greeks used candles on moon-shaped "cakes" of some sort to honor the goddess Artemis's birth on the sixth day of every lunar month. The tradition of putting candles on birthday cakes might be traceable to this custom,[3] but cakes with any resemblance to modern Western birthday cakes only arose by around 1600 in Europe.[4]

Romans began making dipped candles from tallow, beginning around 1000 BC.[5] While oil lamps were the most widely used source of illumination in Roman Italy, candles were common and regularly given as gifts during Saturnalia.[6]

The mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BC), first emperor of China, contained candles made from whale fat.[7] The word zhú was used as candle during the Warring States period (403–221 BCE); some excavated bronzewares from that era feature a pricket thought to hold a candle.[8]

The Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) Jizhupian dictionary of about 40 BC hints at candles being made of beeswax, while the Book of Jin (compiled in 648) covering the Jin Dynasty (266–420) makes a solid reference to the beeswax candle in regards to its use by the statesman Zhou Yi (d. 322).[8] An excavated earthenware bowl from the 4th century AD, located at the Luoyang Museum, has a hollowed socket where traces of wax were found.[8] Generally these Chinese candles were molded in paper tubes, using rolled rice paper for the wick, and wax from an indigenous whale fish.

Wax from boiling cinnamon was used for temple candles in India.[2] Yak butter was used for candles in Tibet.

There is a fish called the eulachon or "candlefish", a type of smelt which is found from Oregon to Alaska. During the 1st century AD, Native Americans from this region used oil from this fish for illumination.[2] A simple candle could be made by putting the dried fish on a forked stick and then lighting it.

Middle Ages

After the collapse of the Roman empire, trading disruptions made olive oil, the most common fuel for oil lamps, unavailable throughout much of Europe. As a consequence, candles became more widely used. By contrast, in North Africa and the Middle East, candle-making remained relatively unknown due to the availability of olive oil.

Candles were commonplace throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. Candle makers (known as chandlers) made candles from fats saved from the kitchen or sold their own candles from within their shops. The trade of the chandler is also recorded by the more picturesque name of "smeremongere", since they oversaw the manufacture of sauces, vinegar, soap and cheese. The popularity of candles is shown by their use in Candlemas and in Saint Lucy festivities.

Tallow, fat from cows or sheep, became the standard material used in candles in Europe. The unpleasant smell of tallow candles is due to the glycerine they contain. The smell of the manufacturing process was so unpleasant that it was banned by ordinance in several European cities. Beeswax was discovered to be an excellent substance for candle production without the unpleasant odour, but remained restricted in usage for the rich and for churches and royal events, due to their great expense.

In England and France, candle making had become a guild craft by the 13th century. The Tallow Chandlers Company of London was formed in about 1300 in London, and in 1456 was granted a coat of arms. The Wax Chandlers Company existed prior to 1330 and acquired its charter in 1484. By 1415, tallow candles were used in street lighting. The first candle mould comes from the 15th century in Paris.[9]

In the Middle East, during the Abbasid and Fatimid Caliphates, beeswax was the dominant material used for candle making.[10] Beeswax was often imported from long distances; for example, candle makers from Egypt used beeswax from Tunis.[10] As in Europe, these candles were fairly expensive, and most commoners used oil lamps instead.[10] Elites, though, could afford to spend large sums on expensive candles.[10] For example, the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil spent 1.2 million silver dirhams annually on candles for his royal palaces.[10]

In early modern Syria, candles were in high demand by all socioeconomic classes because they were customarily lit during marriage ceremonies.[10] There were candle makers' guilds in the Safavid capital of Isfahan during the 1500s and 1600s.[10] However, candle makers had a relatively low social position in Safavid Iran, comparable to barbers, bathhouse workers, fortune tellers, bricklayers, and porters.[10]

Modern era

With the growth of the whaling industry in the 18th century, spermaceti, an oil that comes from a cavity in the head of the sperm whale, became a widely used substance for candle making. The spermaceti was obtained by crystallizing the oil from the sperm whale and was the first candle substance to become available in mass quantities. Like beeswax, spermaceti wax did not create a repugnant odor when burned, and produced a significantly brighter light. It was also harder than either tallow or beeswax, so it would not soften or bend in the summer heat. The first "standard candles" were made from spermaceti wax.

By 1800, an even cheaper alternative was discovered. Colza oil, derived from Brassica campestris, and a similar oil derived from rapeseed, yielded candles that produce clear, smokeless flames. The French chemists Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) and Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850) patented stearin in 1825. Like tallow, this was derived from animals, but had no glycerine content.

Industrialization

The manufacture of candles became an industrialised mass market in the mid 19th century. In 1834, Joseph Morgan, a pewterer from Manchester, England, patented a machine that revolutionised candle making. It allowed for continuous production of molded candles by using a cylinder with a moveable piston to eject candles as they solidified. This more efficient mechanized production produced about 1,500 candles per hour, (according to his patent, "with three men and five boys [the machine] will manufacture two tons of candle in twelve hours"). This allowed candles to become an easily affordable commodity for the masses.[11]

At this time, candlemakers also began to fashion wicks out of tightly braided (rather than simply twisted) strands of cotton. This technique makes wicks curl over as they burn, maintaining the height of the wick and therefore the flame. Because much of the excess wick is incinerated, these are referred to as "self-trimming" or "self-consuming" wicks.[12]

In 1848 James Young established the world's first oil refinery at the Alfreton Ironworks in Riddings, Derbyshire. Two paraffin wax candles were made from the naturally occurring paraffin wax present in the oil and these candles illuminated a lecture at the Royal Institution by Lyon Playfair. In the mid-1850s, James Young succeeded in distilling paraffin wax from coal and oil shales at Bathgate in West Lothian and developed a commercially viable method of production.[13] The Paraffin wax was processed by distilling residue left after crude petroleum was refined.

Paraffin could be used to make inexpensive candles of high quality. It was a bluish-white wax, burned cleanly, and left no unpleasant odor, unlike tallow candles. A drawback to the substance was that early coal- and petroleum-derived paraffin waxes had a very low melting point. The introduction of stearin, discovered by Michel Eugène Chevreul, solved this problem.[14][15] Stearin is hard and durable, with a convenient melting range of 54–72.5 °C (129.2–162.5 °F). By the end of the 19th century, most candles being manufactured consisted of paraffin and stearic acid.

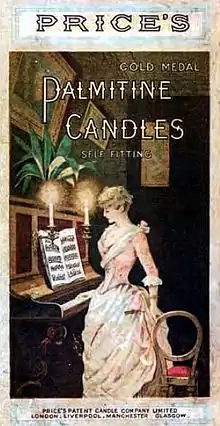

By the late 19th century, Price's Candles, based in London was the largest candle manufacturer in the world.[16] The company traced its origins back to 1829, when William Wilson invested in 1,000 acres (1.6 sq mi; 4.0 km2) of coconut plantation in Sri Lanka.[17] His aim was to make candles from coconut oil. Later he tried palm oil from palm trees. An accidental discovery swept all his ambitions aside when his son George Wilson, a talented chemist, distilled the first petroleum oil in 1854. George also pioneered the implementation of the technique of steam distillation, and was thus able to manufacture candles from a wide range of raw materials, including skin fat, bone fat, fish oil and industrial greases.

In America, Syracuse, New York developed into a global center for candle manufacturing from the mid-nineteenth century. Manufacturers included Will & Baumer, Mack Miller, Muench Kruezer, and Cathedral Candle Company.

Decline of the candle industry

Despite advances in candle making, the candle industry declined rapidly upon the introduction of superior methods of lighting, including kerosene and lamps and the 1879 invention of the incandescent light bulb.

From this point on, candles came to be marketed as more of a decorative item. Candles retain their unique symbolic significance however, for instance as votive offerings. Candles became available in a broad array of sizes, shapes and colors, and consumer interest in scented candles began to grow. During the 1990s, new types of candle waxes were being developed due to an unusually high demand for candles. Paraffin, a by-product of oil, was quickly replaced by new waxes and wax blends owing to rising costs.

Candle manufacturers looked at waxes such as soy, palm and flax-seed oil, often blending them with paraffin in hopes of getting the performance of paraffin with the price benefits of the other waxes. The creation of unique wax blends, now requiring different fragrance chemistries and loads, placed pressure for innovation on the candle wick manufacturing industry to meet performance needs with the often tougher-to-burn formulations. [18]

%252C_Hand_Operated_Candle_Machines_01.jpg.webp) Hand operated, water cooled, candle making machines

Hand operated, water cooled, candle making machines%252C_Hand_Operated_Candle_Machines_02.jpg.webp) Candle Factory workshop

Candle Factory workshop%252C_Hand_Operated_Candle_Machines_03.jpg.webp) 12" Candles wound out from hand-operated machine

12" Candles wound out from hand-operated machine%252C_Staff_Packing_Candles.jpg.webp) Workers packing candles into boxes

Workers packing candles into boxes

References

- 1 2 Willhöft, Franz; Horn, Rudolf (2000). "Candles". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_029. ISBN 3527306730.

- 1 2 3 4 Telesco, Patricia (2001). Exploring Candle Magick: Candle Spells, Charms, Rituals, and Divinations. Career Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-56414-522-0.

- ↑ "Interesting facts about candles you must know about!!". 20 May 2021.

- ↑ "The Cake-Filled History of the Birthday Candle". November 2017.

- ↑ "Candles, Roman, 500 BC". Smith College Museum.

- ↑ "How did the Romans celebrate 'Christmas'?". History Extra. 2013.

- ↑ "Candles in Chinese History". 9 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. pp. 79–80.

- ↑ "A Short History of Candles". Millhouse Candles.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Beg, M.A.J. (1997). "SAMMĀ'". In Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P.; Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. IX (SAN-SZE) (PDF). Leiden: Brill. p. 288. ISBN 90-04-10422-4. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ↑ Phillips, Gordon (1999). Seven Centuries of Light: The Tallow Chandlers Company. Book Production Consultants plc. p. 74. ISBN 1-85757-064-2.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Candles". Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2013-03-23.

- ↑ Golan, Tal (2004). Laws of Men and Laws of Nature: The History of Scientific Expert Testimony in England and America. Harvard University Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 0-674-01286-0.

- ↑ "Using stearic acid or stearin in candlemaking". happynews.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Stearic acid (stearin)". howtomakecandles.info. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Geoff Marshall (2013). London's Industrial Heritage. The History Press. ISBN 9780752492391.

- ↑ Ball, Michael; David Sunderland (2001). An Economic History of London, 1800-1914. Routledge. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0-415-24691-1.

- ↑ Atkins & Pearce Candle Wick History