.jpg.webp)

The Capture of Sint Eustatius took place in February 1781 during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War when British army and naval forces under Lieutenant-General Sir John Vaughan and Admiral George Rodney seized the Dutch-owned Caribbean island of Sint Eustatius. The capture was controversial in Britain, as it was alleged that Vaughan and Rodney had used the opportunity to enrich themselves and had neglected more important military duties. The island was subsequently taken by Dutch-allied French forces in late 1781, ending the British occupation.

Background

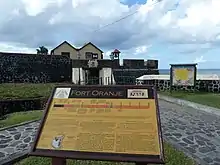

St. Eustatius, a Dutch-controlled island in the West Indies, was an entrepot that operated as a major trading centre despite its relatively small size. During the American War of Independence it assumed increased importance, because a British blockade made it difficult to transport supplies directly across the Atlantic Ocean to US ports. St. Eustatius became a crucial source of supplies, and its harbour was filled with American trading ships. Its importance increased further following France's entry into the war in 1778 as it was used to help supply the French West Indian islands.[1] It is estimated that one half of all the American Revolutionary military supplies were trans-shipped through St. Eustatius. Its merchant networks – Dutch, but also Jewish, many of whom were St. Eustatius residents[2] – were key to the military supplies and goods being shipped to the revolutionary forces. US-European communications were directed through St. Eustatius. In 1776, St. Eustatius, hence the Dutch, were the first to recognize the American Revolutionary government when the US brig, Andrew Doria, fired thirteen guns announcing their arrival. The Andrew Doria was saluted with an eleven gun response from Fort Orange.[3] The Andrew Doria arrived to purchase military supplies on St. Eustatius and to present to the Dutch governor a copy of the US Declaration of Independence. An earlier copy of the Declaration had been captured by a British naval ship. The British were confused by the papers wrapped around the declaration, which they thought were a secret cypher. The papers were written in Yiddish for a merchant in Holland.[2]

St. Eustatius's role in supplying Britain's enemies provoked anger amongst British leaders. Rodney alleged that goods brought out on British convoys had then been sold, through St. Eustatius, to the rebels.[4] It seems to have fuelled a hatred for this island especially with Rodney who vowed to "bring this Nest of Villains to condign Punishment: they deserve scourging and they shall be scourged." He had already singled out several individuals on St. Eustatius who were instrumental in aiding the enemy, such as "... Mr Smith in the House of Jones – they cannot be too soon taken care of – they are notorious in the cause of America and France ..." Following the outbreak of war between the Dutch Republic and Britain in December 1780, orders were sent from London to seize the island. The British were assisted by the fact that the news of the war's outbreak had not yet reached St. Eustatius.[5]

Capture

A British expedition of 3,000 troops sailed from Saint Lucia on 30 January 1781.[6] Rodney left behind ships to monitor the French on Martinique. He also sent Samuel Hood ahead to stop any merchant ships escaping from the harbour. The main force arrived off St. Eustatius on 3 February. Rodney's ships took up position to neutralise any shore batteries. Two or three shots were fired from the only Dutch warship on the roadstead, the frigate Mars under Captain Count Van Bijland.[7] Instead of disembarking the troops and launching an immediate assault, Rodney sent a message to Governor Johannes de Graaff suggesting that he surrender to avoid bloodshed. De Graaff agreed to the proposal and surrendered. De Graaff had ten guns in Fort Orange and sixty soldiers. Rodney had over 1,000 guns on his ships. By the following day the nearby islands of Saint Martin and Saba had also surrendered.[6]

There was a brief exchange of fire when two of the British ships shot at the Mars and Van Bijland answered with his cannons.[8] Rodney reprimanded the captains responsible for this lack of discipline.[9]

The only battle occurred near Sombrero. Rodney found out that a convoy of thirty richly loaded Dutch merchant ships had just sailed off for the motherland less than two days before his arrival, protected only by a single man-of-war. He sent three warships after them, and they quickly caught up with the convoy. The lone Dutch man-of-war was no match for the three British ships and, after a fierce 30-minute pounding, the mortally wounded commander, Rear-Admiral Willem Krul, while dying, ordered his captain to lower the flag. Eight of the Dutch crew were killed. Krul was taken back to St. Eustatius where he was buried with full honours.[10]

The crews of all Dutch ships taken at St. Eustatius and also those of Krul's convoy were stripped of all their possessions and taken to St. Kitts, where they were imprisoned- "with hardly anything more than the most necessary clothes."[11]

Controversy

The wealth Rodney and Vaughan discovered on St. Eustatius exceeded their expectations. There were 130 merchantmen in the bay as well as the Dutch frigate and five smaller American warships. In total the value of goods seized, including the convoy captured off Sombrero, was estimated to be around £3 million.[12] On 5 February 1781, Rodney and Vaughan signed an agreement stating that all goods taken belonged to the Crown.[13] Rodney and Vaughan, by British custom, expected to personally receive a significant share of the captured wealth from the king once it reached England. Instead of delegating the task of sorting through and estimating the value of the confiscated property, Rodney and Vaughan oversaw this themselves. The time spent doing this led to allegations that they had neglected their military duties. In particular, Samuel Hood suggested that Rodney should have sailed to intercept a French fleet under Admiral de Grasse, traveling to Martinique.[14] The French fleet instead turned north and headed for the Chesapeake Bay of Virginia and Maryland. Rodney had further weakened his fleet by sending a strong defending force to Britain to accompany his treasure ships. After months on St. Eustatius, capturing additional merchants and treasure, Rodney was imposed upon to send part of his fleet under Hood north to aid General Cornwallis and British armed forces fighting the Americans, while he took the rest of the fleet back to Britain for some overdue refitting.

Hood arrived at Chesapeake Bay and, finding no French fleet, continued to New York to join forces under Admiral Graves. The French forces under Admiral de Grasse (along with another French squadron from Rhode Island) arrived at the Chesapeake soon after Hood had left. Graves and Hood had been outmaneuvered and, although the resulting Battle of the Chesapeake was a tactical draw, it was a strategic defeat for the British. Cornwallis could not be supplied and was forced to surrender a few weeks later.[15] The Americans had won the war, partially because of Rodney's anti-Semitism and avaricious delays.[16]

After returning home, both officers defended themselves in the House of Commons. As Rodney was a supporter of the government led by Lord North, it approved of his conduct, and he returned to the West Indies for the 1782 campaigning season. When the North government fell and was replaced in 1782, the new government sent orders recalling Rodney. However, before they arrived, he led his fleet to victory at the Battle of the Saintes – ending a Franco-Spanish plan to invade Jamaica – and returned home to be rewarded with a peerage. Rodney survived censure in parliament by a vote strictly along party lines.

At the time, St. Eustatius was home to a significant Jewish community, mainly merchants and a few plantation owners with strong connections to the Dutch Republic. Ten days after the island was captured by Rodney, part of the Jewish community, together with Governor de Graaff, were deported, being given only 24 hours' notice beforehand.[17] Rodney was particularly hard on the Jews. The harshness was reserved for the Jews alone as he did not do the same to French, Dutch, Spanish or American merchants on the island.[18] He even permitted the French to leave with all their possessions. Rodney was concerned that his unprecedented behavior would be repeated upon British islands by French forces when events were different. Rodney imprisoned all the adult Jewish males (101) in the West India Company's weighing house on the Bay. Those who were not immediately shipped to St. Kitts (31 heads of Jewish families) were held there for three days. He pillaged Jewish personal possessions, even cutting open the lining of their clothing to find money hidden there. When Rodney realized that the Jews might be hiding additional treasure, he dug up fresh graves at the Jewish cemetery.[19] Later, Edmund Burke, upon learning of Rodney's actions, rose to condemn Rodney's anti-Semitic, avaricious vindictiveness in parliament.

British control of St. Eustatius only lasted ten months, and Rodney's work to manage the prizes was in vain. Many of the goods he seized were captured on their way to Britain by a French squadron under Toussaint-Guillaume Picquet de la Motte.

Recapture

On the evening of 26 November 1781, 1500 French troops from Fort Royal, led by Marquis de Bouillé, landed covertly at St. Eustatius to take the island. Opposing them were the battalion companies of the 13th and 15th Regiments of Foot, which numbered 756 men. Unaware that the French were on the island, the British commandant, Lieutenant Colonel James Cockburn, was taking a morning ride when he was captured by troops of the Irish Brigade in French service. The Irish and French troops subsequently surprised the British at drill outside the fort and those on guard. The French ran into the fort behind the British and forced the garrison to surrender. Cockburn was afterwards tried by a general court martial and cashiered (forced to retire). There were no significant casualties on either side.[20] Four million livres were taken—170,000 belonging to Admiral Rodney or his troops. These funds were distributed to the French troops and Dutch colonists.[21]

The French returned St. Eustatius to the Dutch in 1784. The Jews and other expelled merchants returned, commerce and trade resumed, and the island's population reached its all-time high in 1790.[22]

Citations

- ↑ Clowes, p. 480.

- 1 2 Klinger, Jerry (June 2004). "How the Jews Saved the American Revolution". The Jewish Magazine. Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Trew, p. 101.

- ↑ Trew, pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 Trew, p. 102.

- ↑ Teenstra, p. 344.

- ↑ Teenstra, p. 345.

- ↑ Trew, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ De Jong, p. 179.

- ↑ Nieuwe Nederlandsche Jaerboeken. 1781. Tweede Stuk, pp. 1080–1081.

- ↑ Trew, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Trew, p. 106.

- ↑ Trew, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ "Battle of the Capes". nps.gov.

- ↑ Klinger, J. "The Jews of St Eustatius" (PDF). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Norton, Louis Arthur. "Retribution: Admiral Rodney and the Jews of St. Eustatius" Jewish Magazine (August 2012).

- ↑ Edmund Burke, in his speech to parliament, noted that the Jews had no army or navy to defend them from Rodney's actions, while the French did.

- ↑ Norton, Louis Arthur (6 March 2017). "Admiral Rodney ousts the Jews from St. Eustatius". allthingsliberty.com. Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ Historical Record of the Fifteenth Regiment of Foot, p. 54.

- ↑ Under the Count de Grasse, p. 93.

- ↑ Hartog, pp. 200–202.

References

- Clowes, William Laird (1996) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume III. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-012-4.

- Hartog, J. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Antillen IV. Aruba, 1960

- Jong, Cornelius de. Reize naar de Caribische Eilanden in de jaren 1780 en 1781. Haarlem, 1807

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson. An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.

- Teenstra, Marten D. De Nederlandsche West-Indische Eilanden. Amsterdam, 1836

- Trew, Peter. Rodney & The Breaking of the line. Pen & Sword, 2006.

Further reading

- Howard, Bryan Paul (1991). Fortifications of St Eustatius: An Archaeological and Historical Study of Defense in the Caribbean Study of Defense in the Caribbean (PDF) (Masters of Arts). College of William & Mary.

- Jameson, J. Franklin (July 1903). "St. Eustatius in the American Revolution". The American Historical Review. Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association. 8 (4): 683–708. doi:10.2307/1834346. JSTOR 1834346.

- Kandle, Patricia Lynn (1985). St Eustatius: Acculturation in a Dutch Caribbean Colony (Master of Arts). College of William & Mary.

- McClellan, William Smith (1912). Smuggling in the American colonies at the outbreak of the Revolution, with special reference to the West Indies trade. New York : Printed for the Department of Political Science of Williams College by Moffat, Yard and Company.