Cashel

Caiseal | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Panorama of town from the Rock of Cashel | |

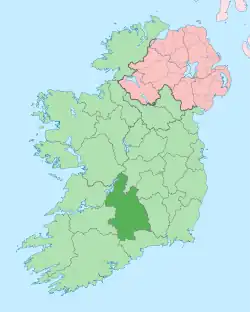

Cashel Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 52°31′00″N 7°53′22″W / 52.516717°N 7.889428°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| County | Tipperary |

| Elevation | 125 m (410 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 4,422 |

| Time zone | UTC0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode | E25 |

| Area code | 062 |

| Irish Grid Reference | S075408 |

| Website | www |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 5,974 | — |

| 1831 | 6,971 | +16.7% |

| 1841 | 7,036 | +0.9% |

| 1851 | 4,650 | −33.9% |

| 1861 | 4,327 | −6.9% |

| 1871 | 4,562 | +5.4% |

| 1881 | 3,961 | −13.2% |

| 1891 | 3,216 | −18.8% |

| 1901 | 2,938 | −8.6% |

| 1911 | 2,813 | −4.3% |

| 1926 | 2,953 | +5.0% |

| 1936 | 3,028 | +2.5% |

| 1946 | 3,063 | +1.2% |

| 1951 | 2,829 | −7.6% |

| 1956 | 2,817 | −0.4% |

| 1961 | 2,679 | −4.9% |

| 1966 | 2,682 | +0.1% |

| 1971 | 2,692 | +0.4% |

| 1981 | 2,754 | +2.3% |

| 1986 | 2,829 | +2.7% |

| 1991 | 2,814 | −0.5% |

| 1996 | 2,957 | +5.1% |

| 2002 | 2,770 | −6.3% |

| 2006 | 2,936 | +6.0% |

| 2011 | 4,051 | +38.0% |

| 2016 | 4,422 | +9.2% |

| [2][3][4] | ||

Cashel (/ˈkæʃəl/; Irish: Caiseal, meaning 'stone ringfort')[5] is a town in County Tipperary in Ireland. Its population was 4,422 in the 2016 census.[1] The town gives its name to the ecclesiastical province of Cashel. Additionally, the cathedra of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly was originally in the town prior to the English Reformation. It is part of the parish of Cashel and Rosegreen in the same archdiocese.[6] One of the six cathedrals of the Anglican Bishop of Cashel and Ossory, who currently resides in Kilkenny, is located in the town. It is in the civil parish of St. Patricksrock[7] which is in the historical barony of Middle Third.

Location and access

The town is situated in the Golden Vale, an area of rolling pastureland in the province of Munster.

Roads

It is located off the M8 Dublin to Cork motorway. Prior to the construction of the motorway by-pass (in 2004), the town was noted as a bottleneck on the N8 Dublin to Cork route.

Bus services

Bus Éireann operates a service (route 245X) between Dublin and Cork which calls at Cashel. Bus Éireann route 128X provides a link to Portlaoise via Urlingford. The Shamrock Bus Company operates a Thurles to Clonmel route via Cashel.

Rail services

Cashel used to be served by a railway, the Cashel spur line, which is now closed. The nearest railway station is Cahir, 17 kilometers away. This station is on an infrequently serviced line, but is useful if travelling east to/from Waterford. The most convenient and frequently serviced rail station for Cashel is Thurles as this is on the Dublin-Cork InterCity rail line.

History

Ancient history

The Rock of Cashel, to which the town below owes its origin, is an isolated elevation of stratified limestone, rising abruptly from a broad and fertile plain called the Golden Vale. The top of this eminence is crowned by a group of remarkable ruins. Originally known as Fairy Hill, or Sid-Druim, the Rock was, in pagan times, the dun, or castle, of the ancient Eoghnacht Chiefs of Munster. In Gaelic, Caiseal denotes a circular stone fort and is the name of several places in Ireland. The "Book of Rights" suggests the name is derived from Cais-il, i.e. "tribute stone", because the Munster tribes paid tribute on the Rock. Here Corc, grandfather of Aengus Mac Natfraich, erected a fort. Cashel subsequently became the capital of Munster and, like Tara and Armagh, it was a celebrated court. At the time of St. Patrick, when Aengus ruled as king, Cashel claimed supremacy over all the royal duns of the province.

In the 5th century, the Eóganachta dynasty founded their capital on and around the rock. Many kings of Munster have reigned here since. Saint Patrick is believed to have baptised Cashel's third king, Aengus. In 977 the Dál gCais usurper, Brian Boru, was crowned here as the first non-Eóghanacht king of Cashel and Munster in over five hundred years. In 1101 his great-grandson, King Muirchertach Ua Briain, gave the place to the bishop of Limerick, thus denying it forever to the MacCarthys, the senior branch of the Eóganachta. The bishops had a famous school in Cashel and sent priests all over the continent, especially to Regensburg in Germany, where they maintained their own monastery, called Scots Monastery.

Lordship of Ireland

The Synod of Cashel of 1172 was organised by Henry II of England. The Synod sought to regulate some affairs of the Church in Ireland and to condemn some abuses, bringing the Church more into alignment with the Roman Rite. It has been suggested that the seventh act of the Synod called upon the clergy and people of Ireland to acknowledge Henry II of England as their king.[8] However, a careful reading of the seventh act would not support this interpretation.[9] Nevertheless, there is little doubt that the King's purpose in requiring the convocation was to overawe the Irish clergy with a display of his power; no doubt he succeeded in this. In this scenario, the convocation would be viewed as a pretext for the show of strength.

St. Dominic's Abbey, a Dominican monastery, was established in 1243. On 30 December 1640, Cashel was captured by an Irish force under Pilib Ó Dubhuir (died 1648) of Dundrum and his brother Donnchadh Ó Dubhuir (hanged in 1652). They took prisoner 300 members of the English garrison and inhabitants. The following day, 15 prisoners were killed as revenge for earlier atrocities against the Irish; however, this was against Ó Dubhuir's orders. In 1647, during the Irish Confederate Wars, the town was stormed and sacked by English Parliamentarian troops under the 6th Baron Inchiquin (later created the 1st Earl of Inchiquin). Over 1,000 Irish Catholic soldiers and civilians, including several prominent clerics, were killed in the attack and ensuing massacre.

Ecclesiastical history

.png.webp)

About 450, Saint Patrick preached at the royal dun and converted king Aengus. The Tripartite Life of the saint relates that while "he was baptising Aengus the spike of the crozier went through the foot of the King" who bore with the painful wound in the belief "that it was a rite of the Faith". According to the same authority, twenty-seven kings of the race of Aengus and his brother Aillil ruled in Cashel until 897, when Cerm-gecan was slain in battle. There is no evidence that St Patrick founded a church at Cashel, or appointed a Bishop of Cashel. St Ailbe, it is supposed, had already fixed his see at Emly, not far off, and within the king's dominions. Cashel continued to be the chief residence of the Kings of Munster until 1100, hence its title, "City of the Kings". Before that date, there was no mention in the native annals of any Bishop, or Archbishop of Cashel. Cormac MacCullinan is referred to, but not correctly, as Archbishop of Cashel, by later writers. He was a bishop, but not of Cashel, where he was king. The most famous man in Ireland of his time, but more of a scholar and warrior than an ecclesiastic, Cormac has left us a glossary of Irish names, which displays his knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and the "Psalter of Cashel", a work treating of the history and antiquities of Ireland. He was slain in 903, in a great battle near Carlow.

Brian Boru (Old Irish: Brian Bóruma) fortified Cashel in 990. Murtagh O'Brien, King of Cashel, in presence of the chiefs and clergy, made a grant in 1101 of the "Rock" with the territory around it to O'Dunan, "noble bishop and chief senior of Munster", and dedicated it to God and St. Patrick. Then Cashel became an archiepiscopal see, and O'Dunan its first prelate as far as the primate, St. Celsus, could appoint him. At the synod of Kells, 1152, Cardinal Paparo gave a pallium to Donat O'Lonergan of Cashel, and since then his successors have ruled the ecclesiastical province of Munster. In 1127 Cormac III of Munster, King of Desmond, erected close to his palace on the "Rock" a church, now known as Cormac's Chapel, which was consecrated in 1134, when a synod was held within its walls. During the episcopate of Donal O'Hullican (1158–1182), the King of Limerick, Domnall O'Brien, built in 1169 a more spacious church beside Cormac's Chapel, which then became a chapterhouse.

Maurice, a Geraldine, filled the see from 1504 to 1523, and was succeeded by Edmund Butler, prior of Athassal Abbey, who was a natural son of Pierce, Earl of Ormond. In addition to the wars between the Irish and the English there arose a new element of discord, the Anglican Reformation introduced by Henry VIII Tudor. While residing at Kilmeaden Castle Archbishop Butler levied black-mail on the traders of the Suir, robbing their boats and holding their persons for ransom. At a session of the royal privy council held at Clonmel in 1539, he swore to uphold the spiritual supremacy of the king and denied the power in Ireland of the Bishop of Rome. He died 1550 and was buried in the cathedral.

Post Reformation

Roland, a Geraldine (1553–1561), was created Archbishop by the Roman Catholic Church at the recommendation of Queen Mary. After a vacancy of six years, Maurice FitzGibbon (1567–1578), a Cistercian abbot, was promoted to the archbishopric by Pope Pius V, but James MacCaghwell (McCawell) was put forward by Elizabeth I of England. Thus began the Anglican religion at Cashel. FitzGibbon, who belonged to the royal Desmond family, being deprived of his see, fled to France and passed into Spain where he resided for a time at the Court. He conferred with the English ambassador at Paris to obtain pardon for leaving the country without the Queen's sanction, and to get permission to return. In this he failed, and going back to Ireland secretly he was arrested and imprisoned at Cork, where he died in 1578. On the death of MacCaghwell, Elizabeth advanced Miler MacGrath, a Franciscan and Bishop of Down, to the See of Cashel. He held at the same time four bishoprics and several benefices, out of which he provided for his numerous offspring. Having occupied the see for fifty-two years, he died in 1622. His monument in the ruined cathedral bears an epitaph written by himself.

Dermot O'Hurley, or Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile, of Limerick, a distinguished student of the university of Louvain in the Duchy of Brabant and professor at Reims in France, was appointed Archbishop of Cashel in 1581 by Pope Gregory XIII. Having presided over the Roman Catholic diocese secretly for two years, he was discovered and brought before the Lord Justices at Dublin, was tortured upon his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy to the English crown and was subsequently hanged outside the city on 20 June 1584.

Following his killing by a relative c. 1724, the severed head of Rapparee and local folk hero Éamonn an Chnoic was displayed spiked upon Cashel Gaol until some local men removed it and gave the head to O'Ryan's sister, who arranged for a Catholic burial.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Dr Butler 2nd (1774–1791), on being appointed to the Roman Catholic diocese, settled in Thurles, where the Roman Catholic archbishops since then have resided. His successor, Archbishop Bray (1792–1820), built a large church in the early part of the 19th century, on the site of which Archbishop Patrick Leahy (1857–1874) erected a splendid cathedral in Romanesque style. It was completed and consecrated in 1879 by Archbishop Croke (1874–1902) and dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption.

St Albert (feast 8 January), a reputed former bishop, is the patron saint of the Roman Catholic diocese. The Archbishop of Cashel is Administrator of the ancient Diocese of Emly.

The Anglican archbishopric was reduced in status by legislation of 1833 and the bishopric combined initially with Waterford. Today the Church of Ireland, Cashel Union of Parishes[11] is part of The Diocese of Cashel, Ferns and Ossory[12]

Tourism

The Rock of Cashel is now one of Ireland's most popular tourist sites. The town has several other attractions, including the Bolton Library.[13]

Cashel Town Hall, which accommodates the Heritage Centre and Tourist Office, on Main Street displays a model of Cashel in the 1640s and a multimedia presentation in several languages, and sells Tipperary crafts. The charters granted by kings Charles II (1663) and James II (1687) are on display in the Heritage Centre.[14]

The Georgian Cathedral Church of St John the Baptist and St Patrick's Rock on John Street (which replaced that on the Rock in the 18th century) and its adjacent Chapter House (which housed the Bolton Library from the 1980s till the 2000s), city walls, and the former Deanery.[11] The former Church of Ireland Archbishop's palace re-opened as a hotel in 2022.[15][16]

St. Dominic's Abbey's ruins are visible southeast of the Rock.

The Cashel Folk Village includes replica displays of country life in early Ireland, including an old public house, a butcher's shop, a farmhouse, a Traveller's caravan, and a chapel. It also includes republican monuments commemorating Tipperary's role in the Anglo-Irish War and Irish Civil War.

A street in Christchurch, New Zealand, is named after the bishopric.[17]

Sport

Cashel King Cormacs GAA is the local Gaelic Athletic Association club.

Other local sports teams include Cashel Town Football Club (a local association football club) and Cashel RFC (the local rugby union club).

People

- John M. Feehan (1916–1991), author and publisher, was born here

- Denis Fogarty, rugby player for Ireland and Munster

- Stephen Garvin, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Denis Leamy, rugby player for Ireland and Munster

- Robert Peel, began his parliamentary career as Member of Parliament for the Cashel constituency

- Kevin Thornton, celebrity chef

- Lumsden Hare, actor – (1874–1964)

See also

Source and references

- 1 2 "Census 2016 – Small Area Population Statistics (SAPMAP Area) – Settlements – Cashel". Census 2016. Central Statistics Office. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ↑ http://www.cso.ie/census Archived 20 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine and http://www.histpop.org Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Post 1961 figures include environs of Cashel For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see JJ Lee "On the accuracy of the pre-famine Irish censuses" in Irish Population, Economy and Society edited by JM Goldstrom and LA Clarkson (1981) p54, and also "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850" by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 4 (November 1984), pp. 473–488.

- ↑ "Census 2006 – Volume 1 – Population Classified by Area" (PDF). Central Statistics Office Census 2006 Reports. Central Statistics Office Ireland. April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ "SAPMAP 2011 – Cashel". CSO. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland". Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Parish of Cashel and Rosegreen, diosesan website. Archived 28 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland – civil parish and barony details". Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ↑ McCormick, Stephen J. (1889). The Pope and Ireland. San Francisco: A. Waldteufel. p. 54.

- ↑ Todd, William Gouan. A History of the ancient church in Ireland. p. Chapter XII.

- ↑ Stephen Dunford (2000), The Irish Highwaymen, Merlin Publishing. Pages 103–104.

- 1 2 "Cashel Cathedral". cashelunion.ie. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "Welcome". Diocese of Cashel, Ferns and Ossory. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "10 ways to get a different take on Ireland". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ Cashel (5 December 2016). "Cashel Heritage Centre". Cashel. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ "Church of Ireland – A Member of the Anglican Communion". www.ireland.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "Cashel Palace Hotel Opens its Magnificent Doors following Major Refurbishment". Hotel and Restaurant Times. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ↑ "Cashel Street was so named by Captain Joseph Thomas, the [[Canterbury Association]]'s chief surveyor and his assistant Edward Jolie" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2012.