| Gracile capuchin monkey[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

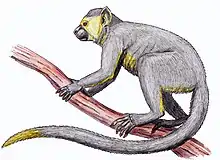

| Panamanian white-headed capuchin (Cebus imitator) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cebidae |

| Subfamily: | Cebinae |

| Genus: | Cebus Erxleben, 1777 |

| Type species | |

| Simia capucina [2] | |

| Species | |

|

Cebus aequatorialis | |

Gracile capuchin monkeys are capuchin monkeys in the genus Cebus. At one time all capuchin monkeys were included within the genus Cebus. In 2011, Jessica Lynch Alfaro et al. proposed splitting the genus between the robust capuchin monkeys, such as the tufted capuchin, and the gracile capuchins.[1] The gracile capuchins retain the genus name Cebus, while the robust species have been transferred to Sapajus.[1][3]

Taxonomy

Following Groves (2005), taxa within the genus Cebus include:[4]

- White-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons

- Ecuadorian capuchin, Cebus albifrons aequatorialis

- Humboldt's white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons albifrons

- Shock-headed capuchin, Cebus albifrons cuscinus

- Trinidad white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons trinitatis

- Spix's white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons unicolor

- Varied capuchin, Cebus albifrons versicolor

- White-headed capuchin or white-faced capuchin, Cebus capucinus

- Kaapori capuchin, Cebus kaapori

- Wedge-capped capuchin, Cebus olivaceus

Subsequent revisions have split some of these into additional species:[5]

- Colombian white-faced capuchin or Colombian white-headed capuchin, Cebus capucinus

- Panamanian white-faced capuchin or Panamanian white-headed capuchin, Cebus imitator

- Marañón white-fronted capuchin, Cebus yuracus

- Shock-headed capuchin, Cebus cuscinus

- Spix's white-fronted capuchin, Cebus unicolor

- Humboldt's white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons

- Guianan weeper capuchin, Cebus olivaceus

- Chestnut capuchin, Cebus castaneus

- Ka'apor capuchin, Cebus kaapori

- Trinidad white-fronted capuchin, Cebus trinitatis

- Venezuelan brown capuchin, Cebus brunneus

- Sierra de Perijá white-fronted capuchin, Cebus leucocephalus

- Río Cesar white-fronted capuchin, Cebus cesare

- Varied white-fronted capuchin, Cebus versicolor

- Santa Marta white-fronted capuchin, Cebus malitiosus

- Ecuadorian white-fronted capuchin, Cebus aequatorialis

The placement of the Trinidad white-fronted capuchin is controversial; the American Society of Mammalogists classifies it as conspecific with C. brunneus based on a 2012 study later found to be flawed, while the IUCN Red List classifies it as a distinct species (Cebus triniatis) due to debate over the aforementioned study, and the ITIS classifies it as a subspecies of C. albifrons, also due to debate over the aforementioned study.[6][7][8][9]

Taxonomic history

Philip Hershkovitz and William Charles Osman Hill published taxonomies of the capuchin monkeys in 1949 and 1960, respectively.[1] These taxonomies established four species of capuchin monkey in the genus Cebus. One of those species, Cebus apella, is a robust capuchin and is now included in the genus Sapajus. The other three Cebus species included in that taxonomy were the gracile capuchin species Cebus albifrons, Cebus nigrivittatus and the type species Cebus capucinus.[3] Cebus nigrivittatus was subsequently renamed Cebus olivaceus.[3][10] Cebus kaapori had been considered a subspecies of C. olivaceus but Groves (2001 and 2005) and Silva (2001) regarded it as a separate species.[11]

Evolutionary history

The gracile capuchins, like all capuchins, are members of the family Cebidae, which also includes the squirrel monkeys. The evolution of the squirrel monkeys and capuchin monkeys is believed to have diverged about 13 million years ago.[1] According to genetic studies led by Lynch Alfaro in 2011, the gracile and robust capuchins diverged approximately 6.2 million years ago.[1][3] Lynch Alfaro suspects that the divergence was triggered by the creation of the Amazon River, which separated the monkeys in the Amazon north of the Amazon River, which evolved into the gracile capuchins, from those in the Atlantic Forest south of the river, which evolved into the robust capuchins.[1][3]

Morphology

Gracile capuchins have longer limbs relative to their body size compared with robust capuchins.[1] Gracile capuchins also have rounder skulls and other differences in skull morphology.[1] Gracile capuchins lack certain adaptations for opening hard nuts which robust capuchins have.[1] These include differences in the teeth and jaws, and the lack of a sagittal crest.[1] Exterior differences include the fact that, although some females have tufts on their head (Humboldt's white-fronted capuchin and Guianan weeper capuchin), no male gracile capuchin has tufts, while all robust capuchins have tufts.[1] Also, no gracile capuchins have beards.[1]

Distribution

Gracile capuchin monkeys have a wide range over Central America and north and north-west South America. The Panamanian white-headed capuchin is the most northern species, occurring in Central America from Honduras to Panama.[5] The Colombian white-headed capuchin also has a northern distribution in Colombia and Ecuador west of the Andes.[5] The white-fronted capuchin is found over large portions of Colombia, Peru and western Brazil, as well as into southern Venezuela and northern Bolivia.[12] The weeper capuchin is found over much of Venezuela and over The Guianas, as well as part of northern Brazil.[10] The Kaapori capuchin has a range that is disjoint from the other gracile capuchins, living in northern Brazil within the states of Pará and Maranhão.[11] The only species to inhabit the Caribbean islands is the Trinidad white-fronted capuchin.

Behaviour

Tool use

Some gracile capuchins are known to use tools. These include white-headed capuchins rubbing secretions from leaves over their bodies, using leaves as gloves when rubbing fruit or caterpillar secretions and using tools as a probe.[1][13] White-fronted capuchins have been observed using leaves as a cup to drink water.[13]

Mating systems

Male weaponry

Intrasexual selection, or male-male competition, occurs when males invoke contests in order to gain the opportunity to reproduce with a female and maximize their reproductive success.[14] Often males are adorned with weaponry, which can be used in order to increase their chances of winning contests for possible mates.[15] In the genus Cebus, there is a large amount of dimorphism in canine size between males and females.[15] Canines are hypothesized to be larger in males because canine dimorphism is generally correlated to male-male competition.[15] In the wedge-capped capuchin there is a larger amount of canine dimorphism compared to the white-faced capuchin and the white-fronted capuchin.[15] The difference in canine dimorphism between these species can be correlated to the differences in social structure of these three groups. The alpha male of the wedge-capped capuchin tends to monopolize mating, therefore engaging in more male-male competition, while in the white-faced capuchin and in the white-fronted capuchin the alpha male does not monopolize mating and allows subordinate males to mate with females.[15] While not much is known about the Kaapori capuchin, due to its low population size, it is likely it would possess more canine dimorphism, like the wedge-capped capuchin, because of its similar social structure with a monopolizing alpha male and peripheral subordinate males.[16]

Direct and indirect female benefits

If a female is presented an opportunity to copulate with a male she will evaluate both the costs and benefits of that male. Females can obtain direct benefits from males she mates with, where the female gains an instant benefit from the male to herself.[17] Direct benefits that would apply to females of the genus Cebus would include; vigilance from males,[18] protection from predators and conspecifics,[17] and increased resources.[19] Females can also benefit indirectly from males, in the form of phenotypic and genotypic benefits to her offspring[20] as well as male protection of those offspring.[17] Alpha males are more fit, and therefore more likely, to provide direct and indirect benefits to the female compared to other subordinate males.[17] In the white-faced capuchin the alpha male fathers 70-90% of the offspring produced by females in his group.[17] It is hypothesized that females are mating with alpha males while they are ovulating and then mating with subordinate males after they are no longer conceptive.[17] Some female primates, like in the white-fronted capuchin, will mate will subordinate males while they are no longer conceptive in order to decrease the amount of resource competition and increase the amount of male protection for her offspring.[18]

Parental care

Capuchin infants are born in an altricial state, which means they need a lot of parental care in order to survive.[21] The majority of parental care in the genus Cebus is provided by the mother, but in the case of the wedge-capped capuchin, parental care is also provided by other conspecific females; this type of care is referred to as allomaternal care.[21] In the wedge-capped capuchin, the mother will provide the infant care for the first three months, however for the next three months the infant relies on the care of other females.[21] In agreement with kin selection theory, kin of the mother are more likely to provide care to the infant compared to other females in the group; siblings were four times as likely to provide infant care compared to other group females.[21] Male parental care is rare in the genus Cebus, only in the white-headed capuchin is there some interaction between males and offspring.[22] In white-headed capuchins males will often investigate, or at least tolerate, their offspring.[22] Alpha males are also more likely to interact with their offspring than subordinate males.[22]

Conservation status

All gracile capuchin species except the Kaapori capuchin are rated as least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[23][10][12] The Kaapori capuchin is rated as critically endangered.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lynch Alfaro, J.W.; Silva, j.; Rylands, A.B. (2012). "How Different Are Robust and Gracile Capuchin Monkeys? An Argument for the Use of Sapajus and Cebus". American Journal of Primatology. 74 (4): 1–14. doi:10.1002/ajp.22007. PMID 22328205. S2CID 18840598.

- ↑ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lynch Alfaro, J.W.; et al. (2011). "Explosive Pleistocene range expansion leads to widespread Amazonian sympatry between robust and gracile capuchin monkeys" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 39 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02609.x. S2CID 13791283. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-26.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 Mittermeier, Russell A.& Rylands, Anthony B. (2013). Mittermeier, Russell A.; Rylands, Anthony B.; Wilson, Don E. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume 3, Primates. Lynx. pp. 407–413. ISBN 978-8496553897.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Boubli, Jean P.; et al. (2012). "Cebus Phylogenetic Relationships: A Preliminary Reassessment of the Diversity of the Untufted Capuchin Monkeys" (PDF). American Journal of Primatology. 74 (4): 1–13. doi:10.1002/ajp.21998. PMID 22311697. S2CID 12171529. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- ↑ Seyjagat, J.; Biptah, N.; Ramsubage, S.; Lynch Alfaro, J.W. (2021). "Cebus trinitatis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T4085A115560059. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T4085A115560059.en. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ "ITIS - Report: Cebus albifrons". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ↑ "Explore the Database". www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- 1 2 3 Boubli, J.P.; Urbani, B.; Lynch Alfaro, J.W.; Laroque, P.O. (2021). "Cebus olivaceus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T81384371A191708662. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T81384371A191708662.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 Kierulff, M.C.M. & de Oliveira, M.M. (2008). "Cebus kaapori". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T40019A10303725. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T40019A10303725.en.

- 1 2 Link, A.; Boubli, J.P.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Urbani, B.; Ravetta, A.L.; Guzmán-Caro, D.C.; Muniz, C.C.; Lynch Alfaro, J.W. (2021). "Cebus albifrons". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39951A191703935. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39951A191703935.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 Garber, P.A.; Gomez, D.F. & Bicca-Marques, J.C. (2011). "Experimental Field Study of Problem-Solving Using Tools in Free-Ranging Capuchins (Sapajus nigritus, formerly Cebus nigritus)". American Journal of Primatology. 74 (4): 344–58. doi:10.1002/ajp.20957. PMID 21538454. S2CID 39363765. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ↑ Wiley, R. Haven; Poston, Joe (1996). "Perspective: Indirect Mate Choice, Competition for Mates, and Coevolution of the Sexes". Evolution. 50 (4): 1371–1381. doi:10.2307/2410875. JSTOR 2410875. PMID 28565703.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Masterson, Thomas (2003). "Canine Dimorphism and Interspecific Canine Form in Cebus". International Journal of Primatology. 24: 159–178. doi:10.1023/A:1021406831019. S2CID 22642329.

- ↑ Fragaszy, Dorothy (2004). The Complete Capuchin: The Biology of the Genus Cebus. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 406.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fisher, Maryanne L.; Garcia, Justin R.; Chang, Rosemarie Sokol (2013-03-28). Evolution's empress : Darwinian perspectives on the nature of women. Fisher, Maryanne., Garcia, Justin R., 1985-, Chang, Rosemarie Sokol. Oxford. ISBN 9780199892747. OCLC 859536355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 van Schaik, C. P.; Noordwijk, M. A. van (1989). "The Special Role of Male Cebus Monkeys in Predation Avoidance and Its Effect on Group Composition". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 24 (5): 265–276. doi:10.1007/BF00290902. JSTOR 4600275. S2CID 30473544.

- ↑ O'Brien, Timothy G. (1991). "Female-male social interactions in wedge-capped capuchin monkeys: benefits and costs of group living". Animal Behaviour. 41 (4): 555–567. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80896-6. S2CID 53202962.

- ↑ West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (1979). "Sexual Selection, Social Competition, and Evolution". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 123 (4): 222–234. JSTOR 986582.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Brien, Timothy G.; Robinson, John G. (1991). "Allomaternal Care by Female Wedge-Capped Capuchin Monkeys: Effects of Age, Rank and Relatedness". Behaviour. 119 (1/2): 30–50. doi:10.1163/156853991X00355. JSTOR 4534974.

- 1 2 3 Sargeant, Elizabeth J.; Wikberg, Eva C.; Kawamura, Shoji; Jack, Katharine M.; Fedigan, Linda M. (2016-06-01). "Paternal kin recognition and infant care in white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus)". American Journal of Primatology. 78 (6): 659–668. doi:10.1002/ajp.22530. ISSN 1098-2345. PMID 26815856. S2CID 3802355.

- ↑ de la Torre, S.; Moscoso, P.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Rosales-Meda, M.; Palacios, E.; Link, A.; Lynch Alfaro, J.W.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2021). "Cebus capucinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T81257277A191708164. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T81257277A191708164.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.