|

|---|

|

|

The history of the Costa Rican legislature is long and starts from even before its formal independence from the Spanish Empire. Costa Rica is one of the world's oldest democracies, thus, its parliamentary history dates back several centuries.

General overview

.jpg.webp)

During the Spanish monarchy time prior to the Cortes of Cádiz, in which the Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated, the power to create laws resided in the King.[1] In 1812 this Constitution is enacted by the Cortes Generales and it establishes that it is up to them to propose and decree laws in conjunction with the Monarch, as well as to interpret and repeal them if necessary. It applied to Costa Rica between its decree on March 19, 1812, and the return to the throne of Ferdinand VII of Spain in mid-1814. It was again inforced from the first months of 1820 to December 1, 1821. Some parts of its text was incorporated in the first constitutions of independent Costa Rica. One deputy was elected for every 70,000 inhabitants in a Province. Costa Rica had as its representative before the Cortes the presbyter Florencio del Castillo.[1]

At the time of the independence from Spain in 1821, the Interim Fundamental Social Pact of the Province of Costa Rica was enacted, also known as the Pact of Concord, which governed from December 1, 1821, to March 19, 1823. It contemplated the annexation to the First Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide. In the Pact of Concord, a Provisional Government Junta is established, composed of seven popularly elected members, assuming the authority of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, the political leadership, the provincial deputation and, as a consequence, it could issue and dictate necessary measures to govern.[1]

In 1823, the First Political Statute of the Province of Costa Rica (from March 19 to May 16, 1823) and the Second Political Statute of the Province of Costa Rica (from May 16, 1823, to September 6, 1824) were promulgated. In this period an alliance was forming to become part of the United Provinces of Central America. In both statutes it was stipulated that the government of the province would exercise it to a three-person board called the Diputación de Costa Rica that would last while the Federation was consolidated. It was up to it to form the necessary regulations for the good running of the province and had an internal by-law that regulated its operation. It was also called «Congress».[1]

In 1823 Costa Rica passes from province to state, joins the Federation and approves the text of the Bases of Federal Constitution of 1823, in force in Costa Rica from March to November 1824. In this constitution it contemplated the separation of powers and delegating the approval of the laws in the Legislative Branch, which would reside in a single chamber, called the Federal Congress, composed of representatives at the rate of one for every 30,000 inhabitants, renewable by halves each year. The Federal Senate was also regulated, composed of two members elected popularly by each of the States and renewable by thirds each year, to whom it was appropriate to give or deny the sanction to the laws. It would also have the functions of a mandatory advisor to the Executive Branch and some control authorities.[1]

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Central America was issued in Guatemala on November 22, 1824, but it was in force in Costa Rica until mid-January 1825 and was disregarded when a Constituent Assembly was established on November 14, 1838. It maintains the bicameral system, in which the Congress approves the laws and a Senate only sanctions them, without legislative initiative capacity. The way of choosing representation of both chambers is maintained.[1]

The Fundamental Law of the Free State of Costa Rica is issued in San José on January 21, 1825. It was in force until May 27, 1828, with the coup d'état of Braulio Carrillo Colina. It became effective again between July and December 1842 by decree of the Constituent Assembly of 1842. It was replaced by the Constitution of 1844.[1] The Legislative Branch is established in a Congress of no less than 11 nor more than 21 deputies. It also establishes a Comptroller branch, composed of not less than 3 nor more than 5 popularly elected members. Among other functions, it had the ability to sanction laws.

During the government of Braulio Carrillo Colina the Decree of Basis and Guarantees was issued, which governs from March 8, 1841, to June 6, 1842 (although it was already de facto suspended since the fall of Carrillo on April 12, 1842, after the coup d'état that Francisco Morazán Quesada made). This law establishes a "Supreme State Power", headed by an unmovable Head, assisted by a Consultative Council and a Judicial Council. The Consultative Council is presided over naturally by the Head and knows only of the matters that it convokes.[2]

The Political Constitution of 1844 is issued on April 9, 1844, and ends with the coup d'état of June 7, 1846. This constitution establishes a bicameral system with reciprocal initiative and sanction, a chamber composed of elected representatives directly and a Senate of not less than 5 members, also elected by suffrage.[2]

The Political Constitution of 1847 governs from January 21, 1847, and is replaced in part in 1848. The Legislative branch resides in a Congress composed of 10 deputies and the Vice President of State, who presides over it. This system remains unchanged in the Political Constitution of 1848, which governs from November 30, 1848, to August 14, 1859, but is called "Chamber of Representatives."

Back to the bicameral system, in the Political Constitution of 1859 (governed from December 26, 1859, to November 2, 1868) and the Constitution of 1869 (from February 18, 1869, to April 27, 1870), establishes a Chamber of Senators composed of two senators for each province and the Chamber of Representatives. Both chambers had initiative in the formation of the law.[3]

The Political Constitution of 1871 was issued and sanctioned on December 7, 1871. It was without effect on September 11, 1877 with the coup d'état of Tomás Guardia Gutiérrez. It became effective again on April 26, 1882. It ceased to rule during the period of the Constitution of 1917 and came into force once again until May 8, 1948. It established the power to legislate in the Constitutional Congress, composed of 43 tenure deputies and 18 alternates, proportionally elected by provinces at the rate of one tenure for every 15,000 inhabitants with a residual system.[3]

After the coup d'état of Federico Tinoco Granados against President Alfredo González Flores, a new constituent assembly was convened and the Political Constitution of 1917 was promulgated, which governed from June 8, 1917, to September 3, 1919, when the government fell for the revolution led by Julio Acosta García. This constitution, which lasted for two years, was drafted by the presidents Bernardo Soto Alfaro, Rafael Iglesias Castro, Ascensión Esquivel Ibarra, Cleto González Víquez and Carlos Durán Cartín.[2] José Joaquín Rodríguez Zeledón excused himself using health reasons and Ricardo Jiménez Oreamuno alleged that he was on his farm. It established a bicameral legislative branch, based on a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate, both of popular election.[2] Each province elected one deputy for every 20,000 inhabitants and three tenure senators and one alternate.[3]

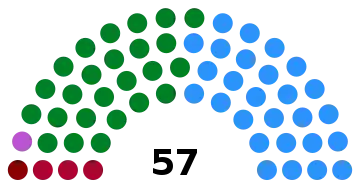

With the Costa Rican Civil War in 1948 that overthrew the government of Teodoro Picado Michalski, the constitutional order was broken yet again and the Founding Junta of the Second Republic, headed by José Figueres Ferrer, took over. A constituent assembly is convened and the Political Constitution of 1949 is enacted, in place up to this date. In this constitution the unicameral system of 1871 is maintained and the number of deputies is fixed at 45, with the provision that when the population exceeds 1,350,000 inhabitants, a new deputy would be elected for every 30,000 or rest. It was also arranged that every three deputies would choose an alternate. Subsequently, by means of Law N ° 2741 of May 12, 1961, the constitutional text was amended to leave the number of deputies fixed at 57 and eliminates the alternates.[3]

Throughout the history of Costa Rica, the first interim governors (1821-1825) had legislative faculties and they had or were attributed by other provisional or de facto governments:[3]

- Braulio Carrillo Colina (1838-1842).

- Francisco Morazán Quesada (1842).

- José María Alfaro Zamora (1842-1844 and 1846-1847).

- Juan Rafael Mora Porras (1852) (While ordered to close the Congress).

- José María Montealegre Fernández (1859-1860).

- Jesús Jiménez Zamora (1863) (While ordered to close the Congress. and 1868-1869).

- Bruno Carranza Ramírez (1870).

- Tomás Guardia Gutiérrez (1870-1872).

- Vicente Herrera Zeledón (1876-1871).

- Tomás Guardia Gutiérrez (1877-1882).

- José Joaquín Rodríguez Zeledón (1892-1894).

- Federico Tinoco Granados (1917).

- Francisco Aguilar Barquero (1919-1920).

Bicamerality

Senate of Costa Rica

The Senate of Costa Rica was the upper chamber of the Costa Rican Legislative branch as prescribed in the constitutions of 1844, 1859, 1869 and 1917. During all these different constitutions, the Senate had different characteristics and conformations.[4]

The Constitution of 1844 established a House of Senators of five senators and their alternates who was renewed by thirds on an annual basis with the possibility of re-election. In the 1859 senators were ten per province that could be re-elected indefinitely and that was renewed every two years.[4] This model was very similar to the Senate of the 1869 Constitution which established 11 senators by province elected for three years and one elected by the Comarca of Puntarenas (which was not yet a province). The longest term of senatorial office was in the 1917 Constitution being of six years, renewing half each three years. One senator was chosen for every three provincial deputies whose number was proportional to the population of the province.[4]

According to Eduardo Oconitrillo García, once the Constitutional Assembly of 1917 was over, and since the senatorial and diputadile elections that were planned for 1919 had not yet taken place, the constituent deputies were divided in such a way that the 14 oldest ones provisionally established the Senate and the 29 youngest the Lower House.[5]

Only the Constitution of 1917 posed the right to naturalized Costa Ricans to be senators, the others required to be Costa Rican by birth. In all, it was a requirement to be over 44 years old, except in 1844, the requirement was to be older than 35. All demanded belonging to the secular state (not being a Catholic priest).[4] The 1917 one also required to be owner or possessor of an income of not less than one thousand colónes. In all constitutions senators obtained parliamentary immunity for which they received immunity except for fragrant criminal acts, although the degree of immunity varied from a constitution to another from full to only civil and during the time of sessions.[4] This fuero could be retired by Congress.[4]

The powers of the Senate varied from one constitution to another, but in the majority it had pre-eminence over the lower house. The 1917 one prescribed that when both chambers would sit together, the president of the Senate would preside over the session. All the constitutions gave the Senate power of initiative of law next to the lower house. Of these only the one of 1844, it states that the Congress is the only one with initiative of law, because the others extend this power to the Executive.[4]

Lower House

The Political Constitution of the Free and Sovereign State of Costa Rica of 1844 expressly prescribes a Congress conformed by a Chamber of Representatives and a Chamber of Senators.[6] This would be abolished in the Constitution of 1847.

The Constitution of 1859 again reintroduces the bicameral congress with a House of Representatives and another of Senators whose powers are described in Article 90.[6] The Constitution of 1869 maintains the figure of the House of Representatives separated from the Senate in its Article 88. It would be abolished in the Constitution of 1871 in which the Parliament returns to be unicameral.[6]

The Chamber of Deputies of Costa Rica was the lower chamber of the Legislative branch prescribed by the Constitution of 1917.[6] The existence of the same lasted only two years since that constituent body was abolished after the overthrow of Federico Tinoco in 1919 and the Constitution was re-established back to 1871 that established a unicameral Congress.[6]

The House was made up of deputies of popular election elected by each province at the rate of a tenure deputy for every fifteen thousand inhabitants or by fraction greater than seven thousand five hundred, plus one deputy for each three tenure and one senator for every three deputies.[6]

The requirements to be a deputy included being a Costa Rican by birth or by naturalization with more than ten years of being nationalized, being over 25 years old, being able to read and write and owning properties with a value of not less than three thousand colónes or an annual income of not less than one thousand. In addition, the President or Vice-Presidents, ministers, magistrates or local authorities could not be deputies. The term lasted six years with indefinite re-election and half of the Chamber had to be renewed each three years (which didn't occurred as the existence of the Chamber did not last that long). The Senate had precedence over the Chamber of Deputies and in fact the Constitution established that in case someone was elected deputy and senator should choose to be a senator and while a senator could be a deputy, a deputy could not be a senator.[6]

Constitutional Congress

Current parliamentary reform debate

Number of seats

The Legislative Assembly of Costa Rica is a unicameral body of 57 deputies whose number is constitutionally fixed and who are elected in closed lists postulated by the political parties by reason of a proportional system. Different experts have recommended the increase in the number of deputies as an urgent need to improve representativeness, but this proposal is highly unpopular among the population and generates reactions of rejection.[7] A report of the United Nations Development Program and the Center of Investigation and Political Studies of the University of Costa Rica recommended to increase the number of legislators to 82.[8] the Northwestern University of Chicago made recommendations for more than 100 countries and recommended that the Costa Rican parliament should had 115 deputies according to its population (in 1999),[9] the Board of Notables for the Reform of the State summoned by President Laura Chinchilla during her tenure recommended to increase the seats to between 75 and 85.[9] The Citizen Power Now Movement on the other hand proposes to increase it to 84 and drastically reduce the number of legislative advisors (currently 12) to avoid a very large increase in expenses.[10] The proposal of the book Aplicación del modelo alemán a la elección de diputados en Costa Rica by lawyer Diego González suggests increasing the number to 143, making use, as the title indicates, of an electoral system similar to the German model.[7]

Most of these proposals also include the switch to direct vote and not by closed lists as it is currently. In the case of the "German model" proposed by Gonzalez, the country would be divided into 72 electoral circuits by 59,700 inhabitants and deputies would be elected in two lists, 72 elected by a single-member district where one deputy is elected directly by each district, and 71 elected by a proportional constituency where they would be proportionally distributed according to the votes received per game.[7]

The proposal of Citizen Power Now is similar, proposes a mixed proportional representation where 42 deputies would be elected, one from each of 42 electoral districts created for that purpose, and the other 42 would be chosen proportionally according to the party's vote and could be reelected consecutively, a maximum of three periods (currently the Costa Rican deputies can not be re-elected consecutively, but they have no limits to be re-elected alternately).[10] When the Constitution of Costa Rica was drafted of 1949, 57 deputies was one for every 14000 inhabitants, currently it is one for every 80,000.[10]

Parliamentary system

Currently Costa Rica is a presidential republic where the president holds both the position of head of state and head of government. It has been suggested to move to a parliamentary system.

One of the first to propose it over the year 2001 was the then President Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Echeverría, as a way to solve the problem of political governability in the country.[11]

This was suggested again by the Commission of Notables for the Reform of the State convened by Laura Chinchilla, and to which belonged the minister of the presidency Rodolfo Piza.[12] A bill present in the legislative current and studied in committee would seek to increase the number of deputies and make the parliament name and remove ministers, able to call early elections if the president receives a vote of no confidence and that the president can dissolve Parliament and hold elections. However is not currently under discussion. The switch to this system has also been endorsed by the deputy and former president of the Social Christian Unity Party Pedro Muñoz, the conservative deputy Mario Redondo, and the historic leader of the Citizens' Action Party Ottón Solís.[13] It was also part of the proposals analyzed in the Legislative Assembly in the Commission of Reforms to the Political System together with other changes such as the direct vote for deputies, their increase in number and a comprehensive reform of the legislative by-law.[14]

The ex-deputy, former minister and former presidential candidate Rolando Araya Monge, who is part of the Second Commission of Notables for State Reform, this time convened by President Carlos Alvarado Quesada, announced that he would propose both the passage to parliamentarism and going back to bicamerality.[15]

Evolution

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Clotilde Obregón Quesada Clotilde (2007). Las Constituciones de Costa Rica. Tomo I. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica. ISBN 978-9968-936-91-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Obregón Quesada, Clotilde (2007). Las Constituciones de Costa Rica. Tomo II. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica. ISBN 978-9968-936-91-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Obregón Loría, Rafael (1966). El Poder Legislativo en Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica: Asamblea Legislativa.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fernández Rivera, Felipe. El Senado en Costa Rica (PDF). Asamblea Legislativa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- ↑ Oconitrillo García, Eduardo (2009). Memorias de un telegrafista de Casa Presidencial. EUNED. ISBN 9789968316897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 García Rojas, Georgina. "Historia del bicameralismo en Costa Rica" (PDF). Revista Parlamentaria. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 González, Diego (2018). "¿Por qué Costa Rica necesita 143 diputados?". p. Contexto CR.

- ↑ Redacción (2017). "ONU recomienda aumentar a 82 la cantidad de diputados". AM Prensa.

- 1 2 Gutiérrez, Marielos (2015). "Proponen aumentar cantidad de diputados y reducir número de asesores". CRHoy.

- 1 2 3 Ramírez, Alexander (2016). "Grupo propone aumentar a 84 el número de diputados". CRHoy.

- ↑ Editorial (2001). "¿Presidencial o parlamentario?". Nación.com.

- ↑ Jiménez Meza, Manrique (2015). "Por un sistema parlamentario de gobierno". La Nación.

- ↑ Muñoz, Pedro (2017). "Pedro Muñoz: Hacia un parlamentarismo a la tica". La Nación.

- ↑ Sequeira, Aaron (2014). "Diputados debaten un viraje hacia el parlamentarismo". Nación.

- ↑ Ruiz, Maureen (2018). "Rolando Araya impulsará ir a un sistema parlamentario". Mundo.