| Chandelier cell | |

|---|---|

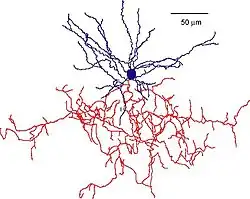

Reconstruction of a mouse chandelier cell. Soma and dendrites are labeled in blue, axon arbor in red. (Woodruff & Yuste, 2008, PLoS Biology)[1] | |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy |

An action potential in a pyramidal neuron (cell 1) elicits a spike in a chandelier cell (2) via a strong connection, in turn evoking a third-order spike in a downstream pyramidal cell (3). This spike results in a trisynaptic EPSP being recorded in a postsynaptic pyramidal cell (cell 4, event A). At the same time, cell 3 drives both a basket cell (5) and chandelier cell (6) to threshold. The basket cell evokes a hyperpolarizing IPSP on the postsynaptically recorded pyramidal cell (cell 4, event B), four synapses removed from the original spike. The spiking chandelier cell (6) triggers yet another pyramidal neuron to fire (7), which produces an EPSP on the recorded neuron (cell 4, event C), five synapses away from the original spike. The result seen in the postsynaptic pyramidal neuron (cell 4) is a delayed EPSP-IPSP-EPSP sequence (events A, B, and C), traveling through three, four, and five synapses respectively. Molnár et al. propose[2] that polysynaptic pathways similar to this one can be activated by a single action potential in a cortical pyramidal cell.

Chandelier neurons or chandelier cells are a subset of GABAergic cortical interneurons. They are described as parvalbumin-containing and fast-spiking to distinguish them from other subtypes of GABAergic neurons, although more recent work has suggested that only a subset of chandelier cells test positive for parvalbumin by immunostaining.[3] The name comes from the specific shape of their axon arbors, with the terminals forming distinct arrays called "cartridges". The cartridges are immunoreactive to an isoform of the GABA membrane transporter, GAT-1, and this serves as their identifying feature.[4][5] GAT-1 is involved in the process of GABA reuptake into nerve terminals, thus helping to terminate its synaptic activity. Chandelier neurons synapse exclusively to the axon initial segment of pyramidal neurons, near the site where action potential is generated.[6] It is believed that they provide inhibitory input to the pyramidal neurons, but there is data showing that in some circumstances the GABA from chandelier neurons could be excitatory. [7]

The axon cartridges formed by chandelier cells are one of the synapse types that show the most dramatic changes during normal adolescence,[8] and could potentially be relevant to the adult onset of psychiatric disease. Furthering this link, in schizophrenia, scientists have observed changes in their form and functionality, such as 40% decrease in the axon terminal density.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 Woodruff A, Yuste R (September 2008). "Of Mice and Men, and Chandeliers". PLoS Biol. 6 (9): e243. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060243. PMC 2553849. PMID 18816168.

- ↑ Molnár G, Oláh S, Komlósi G, Füle M, Szabadics J, Varga C, Barzó P, Tamás G (September 2008). Yuste R (ed.). "Complex events initiated by individual spikes in the human cerebral cortex". PLoS Biol. 6 (9): e222. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060222. PMC 2528052. PMID 18767905.

- ↑ Taniguchi H, Lu J, Huang ZJ (January 2013). "The Spatial and Temporal Origin of Chandelier Cells in Mouse Neocortex". Science. 339 (6115): 70–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...339...70T. doi:10.1126/science.1227622. PMC 4017638. PMID 23180771.

- ↑ Borden, L. A. (1996). "GABA transporter heterogeneity: Pharmacology and cellular localization". Neurochemistry International. 29 (4): 335–356. doi:10.1016/0197-0186(95)00158-1. PMID 8939442. S2CID 25089539.

- ↑ Hardwick, C.; French, S. J.; Southam, E.; Totterdell, S. (2005). "A comparison of possible markers for chandelier cartridges in rat medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus". Brain Research. 1031 (2): 238–244. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.047. PMID 15649449. S2CID 25594278.

- ↑ Contreras, D. (2004). "Electrophysiological classes of neocortical neurons". Neural Networks. 17 (5–6): 633–646. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2004.04.003. PMID 15288889.

- ↑ Szabadics, J.; Varga, C.; Molnár, G.; Oláh, S.; Barzó, P.; Tamás, G. (2006). "Excitatory Effect of GABAergic Axo-Axonic Cells in Cortical Microcircuits". Science. 311 (5758): 233–235. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..233S. doi:10.1126/science.1121325. PMID 16410524. S2CID 40744562.

- ↑ Anderson, S.A.; Classey, J.D.; Condé, F.; Lund, J.S.; Lewis, D.A. (1995). "Synchronous development of pyramidal neuron dendritic spines and parvalbumin-immunoreactive chandelier neuron axon terminals in layer III of monkey prefrontal cortex". Neuroscience. 67 (1): 7–22. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(95)00051-J. ISSN 0306-4522. PMID 7477911. S2CID 25474218.

- ↑ Pierri, J. N.; Chaudry, A. S.; Woo, T. U.; Lewis, D. A. (1999). "Alterations in chandelier neuron axon terminals in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic subjects". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (11): 1709–1719. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.11.1709. PMID 10553733.

External links

- SRF interviews David Lewis - an interview touching on the GABAergic neuronal dysfunction in schizophrenia and the role of the chandelier cells.

- NIF Search - Chandelier Cell via the Neuroscience Information Framework

- Cortical Development - images of chandelier neurons and information on their developmental changes. Translational Neuroscience Program at the University of Pittsburgh.

- How chandelier cells light up human thought - A type of brain cell called a chandelier neuron might be what gives us the edge over other mammals in thought and language, New Scientist, 3 September 2008