| Northern snakehead | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anabantiformes |

| Family: | Channidae |

| Genus: | Channa |

| Species: | C. argus |

| Binomial name | |

| Channa argus (Cantor, 1842) | |

| |

| Asian distribution of Channa argus (native in yellow, introduced in red). Source: USGS 2004[2] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The northern snakehead (Channa argus) is a species of snakehead fish native to temperate East Asia, in China, Russia, North Korea, and South Korea. Their natural range goes from the Amur River watershed in Siberia and Manchuria down to Hainan.[3] It is an important food fish and one of the most cultivated in its native region, with an estimated 500 tons produced every year in China and Korea alone.[4] Due to this, the northern snakehead has been exported throughout the world and has managed to establish non-native populations in Central Asia and North America.

Appearance

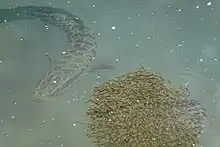

The distinguishing features of a northern snakehead include a long dorsal fin with 49–50 rays,[5] an anal fin with 31–32 rays, a small, anteriorly depressed head, the eyes above the middle part of the upper jaw, a large mouth extending well beyond the eye, and villiform teeth in bands, with large canines on the lower jaw and palatines. It is generally reported to reach a length up to 100 cm (3 ft 3 in),[2][3] but specimens approaching 150 cm (4 ft 11 in) are known according to Russian ichthyologists.[2] The largest registered by the International Game Fish Association weighed 8.05 kg (17 lb 12 oz),[6] although this was surpassed by a 18.42 lb (8.36 kg) northern snakehead caught in 2016.[7]

Its coloration is a golden tan to pale brown, with dark blotches on the sides and saddle-like blotches across the back. Blotches toward the front tend to separate between top and bottom sections, while rear blotches are more likely to be contiguous. Coloration is nearly the same between juveniles and adults, which is unusual among snakeheads, and is similar to Channa maculata, but can be distinguished by two bar-like marks on the caudal peduncle (where the tail attaches); in C. maculata, the rear bar is usually complete, with pale bar-like areas before and after, while in C. argus, the rear bar is irregular and blotched, with no pale areas around it.[2]

Fish similar in appearance

The eyespot bowfin (Amia ocellicauda) and northern snakehead can be found in the same waters on the swampy tidal coastal plain of the mid-Atlantic United States, such as the Potomac and Delaware River, and are commonly confused with each other. Some contrasting differences in northern snakehead include the lack of a black eyespot on their caudal peduncle, a golden tan to brown coloration with dark splotches, a longer anal fin, a more elongated head, and an upper jaw that is shorter than its lower jaw. Another noticeable difference is that northern snakehead scales continue uniformly from their body to their head. The northern snakehead has scales that continue uniformly from the body through to their head, whereas bowfin heads are smooth and free of scales.[8]

Behavior

The northern snakehead is a freshwater species and cannot tolerate salinity in excess of 10 parts per million.[2] It is a facultative air breather; it uses a suprabranchial organ and a bifurcated ventral aorta that permit aquatic and aerial respiration.[9][10]: 10–13 This unusual respiratory system allows it to live outside of water for several days; it can wriggle its way to other bodies of water or survive being transported by humans. Only young of this species (not adults) may be able to move overland for short distances using wriggling motions.[2] The preferred habitats of this species are stagnant water with mud substrate and aquatic vegetation, or slow, murky, swampy streams; it is primarily piscivorous, but is known to eat crustaceans, other invertebrates, and amphibians.[11]

Reproduction

The northern snakehead can double its population in as little as 15 years. It reaches sexual maturity at age three or four, when it will be about 30 to 35 cm (1 ft 0 in – 1 ft 2 in) long. The eggs are fertilized externally; a female can lay 100,000 eggs a year. Fertilization occurs in shallow water in the early morning. The eggs are yellow and spherical, about 2 mm (0.079 in) in diameter. Eggs hatch after about 1–2 days, but they can take much longer at lower temperatures. The eggs are guarded by the parents until egg absorption, when the eggs are about 8 mm (0.31 in) long.[12]

Subspecies

Two subspecies have been recognized:[13]

- C. a. argus (Cantor, 1842) (Northern snakehead) China and Korea

- C. a. warpachowskii Berg, 1909 (Amur snakehead) eastern Russia.

As an invasive species

In its native Asia, the snakehead fish is considered to be an important food fish and for this reason they have been exported to many other regions around the world. They were first introduced to Japan from mainland Asia in the early 1900s, where they have since become a sport fish. The USSR experimented with aquaculture of snakeheads during the mid 20th century in both Europe and Central Asia. In the United States, snakeheads were only cultured in Arkansas, but have managed to establish populations there and several states in the Mid-Atlantic.

Japan

Snakeheads of Korean stock were first introduced to Japan in the 1920s, and since then have spread to about every suitable body of water on the Japanese mainland.[14]

Europe

During the Cold War, the USSR imported several different species of fish from eastern Eurasia into Europe for new prospects in aquaculture. Among these fish was the northern snakehead, which came from the Amur River basin and were stocked in various ponds of the Moscow region starting in 1949.[15] These initial experiments were successful and it was recommended that snakehead be stocked into various other waterbodies. However, only one shipment to Czechoslovakia was ever made in 1955, and nothing else after. The snakehead was also introduced to the Volga Delta and various ponds in Yekaterinburg, but are presumed to have failed due to no reports since then.

While the snakeheads were reported to have been breeding in Moscow in the 1950s, they have since disappeared. There are no known populations in Europe in this moment.

Central Asia

The snakehead has managed to establish themselves in the countries of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, all of which used to be part of the former Soviet Union. More specifically, they are known to be in the Amu Darya, Syr Darya, and Kashka-Darya since the 1960s due to both accidental and intentional releases. Since then, snakeheads have also been introduced to the Sarysu River, Talas River, and Chu River. They have become an important commercial fish in the region, with around 10 metric tons being harvested from just the Talas in 1989.

United States

The fish first appeared in U.S. news when an alert fisherman discovered one in a Crofton, Maryland, pond in the summer of 2002.[16] The snakehead fish was considered to be a threat to the Chesapeake Bay watershed, and wary officials took action by draining the pond in an attempt to destroy the species. The action was successful, and two adults and over 100 juvenile fish were found and destroyed. A man admitted having released two adults, which he had purchased from a New York market, into the pond.[17]

In 2004, 19 northern snakeheads were captured in the Potomac River, and they were later confirmed to have become established (i.e., they were breeding). They are somewhat limited to that stretch of the river and its local tributaries, upstream by the Great Falls, and downstream by the salinity of Chesapeake Bay.[17] Tests found they are not related to northern snakeheads found in other waters in the region, alleviating some concern of their overland migration.[18] Northern snakeheads continue to be caught in the river as of 2022.[19][20]

The northern snakehead has been found in three counties of Florida, and may already be established there. Apparently unestablished specimens have been found in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, New York City, two ponds in Philadelphia,[17] a pond in Massachusetts, and reservoirs in California and North Carolina.[2] In 2008, the northern snakehead was found in drainage ditches in Arkansas as a result of a commercial fish-farming accident. Recent flooding may have allowed the species to spread into the nearby White River, which would allow an eventual population of the fish in the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers.

In the summer of 2008, an infestation of the northern snakehead was confirmed in Ridgebury Lake and Catlin Creek near Ridgebury, New York. By August 2008, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation had collected a number of the native fish, and then poisoned the waters with a liquid rotenone formulation. After the poisoning, the NYSDEC had to identify, measure, and additionally process the fish to adhere with Bureau of Fisheries procedures before disposal. The treatment plan was operated under several agents, and New York State Police were placed on stand-by in case of protests of local residents of the area.

A new concern is that this fish's spreading is getting close to the Great Lakes, which it may enter and disrupt that ecosystem.

When the snakehead was found in Crofton, the piscicide rotenone was added to the three adjacent ponds.[2] This method of containment killed all fish present in the water body to prevent the spread of the highly invasive snakehead. The chemical breaks down rapidly, and has a half-life in water of 1–3 days.[21][22]

In 2012, a snakehead was found in a pond in Burnaby, British Columbia, but further study revealed that it had been released three months or less before its capture and it was a blotched snakehead or perhaps a hybrid involving that species.[23] Unlike the northern snakehead, which potentially can establish a population in parts of Canada, the blotched snakehead generally only lives in warmer waters.[23] Before its exact identity was revealed, the province introduced legislation banning the possession of snakeheads and several other potentially invasive species.[23]

In April 2013, sightings of the species in Central Park's Harlem Meer prompted New York City officials to urge anglers to report and capture any individuals. Ron P. Swegman, author of several angling essays on Central Park's ponds, confirmed the species had put both anglers and the New York State DEP on high alert.[24][25]

In late 2013, authorities in Virginia and Maryland were counting snakeheads in the Chesapeake Bay to better understand the impact of the introduction of the fish to the local ecosystem.[26] Virginia has criminalized the "introduc[tion]" of snakeheads into the state without specific authorization, although the relevant statute does not explain whether mere importation is sufficient to constitute "introduc[tion] into the Commonwealth" or whether instead release into the environment is required.[27]

In October 2019, multiple snakeheads were found in a pond on private property in Georgia.[28][29][30]

In August 2021, a 30-inch snakehead weighing 5 pounds was caught in a reservoir in Canton, Massachusetts.[31]

World record

On the night of May 24, 2018, Andrew “Andy” Fox of Mechanicsville, Maryland shot a northern snakehead with a bow and arrow, which was officially listed as the biggest ever shot according to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. The record-breaking northern snakehead weighed 19.9 lb, with a length of 35.157 inches. The snakehead was shot near Indian Head, Mattawoman Creek, in Charles County, Maryland.[32]

On May 20, 2014, Luis Aragon of Triangle, Virginia, caught a 17 lb 12 oz (8.05 kg) northern snakehead, which was officially listed as the biggest ever caught on rod and reel, according to the International Game Fish Association.[6] On May 20, 2016, Emory "Dutch" Baldwin of Indian Head, Maryland boated an 18.42 lb (8.36 kg) northern snakehead in tidal marshes of the Potomac using archery tackle. This fish is listed as the state sport record in Maryland by the Department of Natural Resources.[7]

In traditional culture

Northern snakeheads are respected among some Chinese fishermen for their virtue, as parent snakefish are known to sacrifice themselves to protect their young. The young fish are said to rush to feed upon their mother after she gives birth and is temporarily unable to catch prey.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ Bogutskaya, N. (2022). "Channa argus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T13151166A13151169. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T13151166A13151169.en. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Courtenay, Walter R.; Williams, James D. (2004). "Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae): A biological synopsis and risk assessment". Circular. doi:10.3133/cir1251. hdl:2027/umn.31951d02062442x. Courtenay W. R. Jr., and J. D. Williams. (2004). "Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae).—A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment", U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251.

- 1 2 3 Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2019). "Channa argus" in FishBase. August 2019 version.

- ↑ Whedbee, Jeffrey. "Channa argus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ↑ Hogan, C.Michael (2012). Northern Snakehead. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. E.Monosson & C.Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment.] Washington DC.

- 1 2 "IGFA World Record".

- 1 2 "Dutch Baldwin sets snakehead record at 18.42 pounds". Baltimore Sun. 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ↑ "Bowfin vs Snakehead 101: How to Tell the Difference | Wild Hydro". Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ↑ Ishimatsu, Atsushi; Itazawa, Yasuo (1981). "Ventilation of the air-breathing organ in the snakehead Channa argus". Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. 28 (3): 276–282. doi:10.11369/jji1950.28.276.

- ↑ Ishimatsu, Atsushi (2012). "Evolution of the Cardiorespiratory System in Air-Breathing Fishes" (PDF). Aqua-BioScience Monographs. 5 (1): 1–28. doi:10.5047/absm.2012.00501.0001. Retrieved 4 September 2023 – via CORE, The Open University.

- ↑ Caspers, H. (1968). "YAICHIRO OKADA: Studies on the Freshwater Fishes of Japan. With 61 plates, 133 text-fig., 135 tables. Japan: Prefectural University of Mie; Tsu, Mie Prefecture 1959- 1960. 862 pp". Internationale Revue der Gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie. 53: 162. doi:10.1002/iroh.19680530109.

- ↑ "Issg Database: Ecology of Channa Argus." Issg Database: Ecology of Channa Argus. N.p., 21 May 2009. Web. 26 Mar. 2016.

- ↑ "Amur snakehead – Channa argus warpachowskii (Berg, 1909) ― Synonym of Channa argus". European Environment Agency (EEA). Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ↑ "Channa argus". Invasive Species of Japan. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ↑ "Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae) - A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251. 2004 – via U.S. Geological Survey.

- ↑ Fields, Helen (February 2005). "Invasion of the Snakeheads". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- 1 2 3 Potomac snakeheads not related to others Baltimore Sun, 2007-04-27.

- ↑ Orrell, Thomas M.; Weigt, Lee (2005). "The Northern Snakehead Channa argus (Anabantomorpha: Channidae), a non-indigenous fish species in the Potomac River, U.S.A." (PDF). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 118 (2): 407. doi:10.2988/0006-324X(2005)118[407:TNSCAA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-324X. S2CID 82418306. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-13.

- ↑ US Department of Interior "NAS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species" https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/CollectionInfo.aspx?SpeciesID=2265&State=DC&YearFrom=2022&YearTo=2022

- ↑ Fahrenthold, David A. (2007-07-08) Potomac Fever Washington Post, Page W12. Retrieved on 2007-07-16.

- ↑ "Rotenone". Pesticides News. 54: 20–21. 2001.

- ↑ Material Fact Sheets – Rotenone Resource Guide for Organic and Disease Management. Cornell University. Retrieved on 2007-07-16. Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Simon Fraser University (22 November 2013). CSI-type study identifies snakehead.

- ↑ Kassel, Matthew (2013-05-28) Gone Fishin’: Casting for Invasive Species in Central Park. observer.com

- ↑ Strahan, Tracie (2013-04-30). "Invasive predator fish that can live out of water for days to be hunted in Central Park". NBC News. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- ↑ "Snakehead fish: Can invasive species be eaten out of existence?". BBC News. 2013-09-03. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- ↑ Code of Virginia § 18.2–313.2: "Any person who knowingly introduces into the Commonwealth any snakehead fish of the family Channidae[...] without a permit from the Director of Game and Inland Fisheries [...] is guilty of a class 1 misdemeanor [punishable by up to twelve months in jail and/or a fine of up to $2,500]."

- ↑ "Invasive Snakehead Fish Caught in Gwinnett County". Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

- ↑ Culver, Jordan (2019-10-09). "'Kill it immediately': Invasive fish that can breathe air, survive on land found in Georgia". USA TODAY.

- ↑ "First record of occurrence and genetic characterization of a population of northern snakehead Channa argus (Cantor, 1842) in Georgia, USA" (PDF).

- ↑ "Man catches rare invasive snakehead fish in Canton reservoir. In June of 2022 Northern Snakeheads were discovered in a man-made lake that resides as part of a planned unit development in Evesham, New Jersey". Boston.com.

- ↑ Mechanicsville Man Catches Record Snakehead in Charles County. Maryland Department of Natural Resources (2018-05-30)

- ↑ 数万鱼苗漂到哪,黑鱼夫妻就守到哪·杭州日报 (in Chinese)

Further reading

- "Channa argus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 January 2006.

- Anonymous. 2005. 2005 World Record Game Fishes. International Game Fish Association, Dania Beach, FL. 400 pp.

- Graham, J. B. 1997. Air-breathing fishes: evolution, diversity, and adaptation. Academic Press, San Diego, California, xi + 299 pp

External links

- InvadingSpecies.com

- Recognizing Northern Snakehead

- Northern Snakehead

- Species Profile- Northern Snakehead (Channa argus), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for Northern Snakehead.